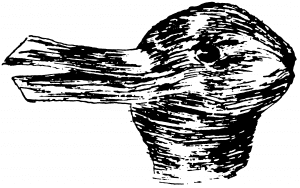

Remember the Duck Rabbit? That’s the famous image that, seen one way, looks like a duck but, seen from another angle, looks like a rabbit. The image has provided fodder for children’s books and also philosophers, its inherent ambiguity being catnip to both light fancy and epistemological lucubration.

I thought of that teasing graphic confection when I encountered “The Final Year,” Greg Barker’s HBO documentary about the last 12 months of the Obama Administration’s foreign policy. At first I thought it was intended to be a duck: a sympathetic portrait of its main characters: President Obama himself, of course, but also Secretary of State John Kerry, our ambassador to the United Nations, Samantha Power, and Deputy National Security Advisor Ben Rhodes. But the more I watched, the more the rabbit theme intruded: the more, I mean, that it struck me as a devastating portrait of mandarin entitlement gone horribly wrong.

I am really uncertain what Greg Barker intended. He indulges in no editorializing. The camera follows the principals around the world and simply captures their speeches and conversations: Samantha Power and John Kerry, President Obama at the U.N., Obama on his final trip to Greece, Ben Rhodes padding about the White House and elsewhere. It’s all presented in a very straightforward way to outline the Obama Administration’s ambitions as well as its frustrations as world events—the mess in Syria, the unbelievable election of Donald Trump—unfold around them.

The main characters are given plenty of on-air time to explain what they hope to accomplish and also to describe the forces, domestic as well as international, that they see as frustrating their aims.

The portrait of Ben Rhodes was particularly poignant. Two scenes stand out. One was his reaction to the news that, somehow, Donald Trump had won the 2016 election. Those with a robust appetite for Schadenfreude will regard it as hilarious if pathetic. Others will find it pathetic and sad. For me, I have to admit, it brought to mind Oscar Wilde’s comment that a man would have to have a heart of stone to read Charles Dickens’s account of the death of Little Nell without laughing. The camera follows Rhodes walking alone off a stage just after the terrible news came down. “I just came outside to try to process all of this,” Rhodes says haltingly. “It’s a lot to process. I mean, ah . . . I can’t even . . . I can’t . . . I mean I . . . I can’t put it into words. I don’t know what the words are.”

That took one minute and five seconds.

It’s as if you were sitting at home in Athens and just got the news from Aegospotami that the Spartans had destroyed your fleet meaning that, after nearly three decades, you had just lost the war. How could this have happened?

In order to understand the shattering surprise that gripped team Obama, it is necessary to appreciate the sensation of absolute moral superiority that wafted them along. This was no mere election. It was a fight between good and evil. And they were in no doubt that they were the good guys. “Cuba, climate, Iran,” Rhodes says, what will happen to those things now that Donald Trump is in charge? Note that he puts forward those items as if they were triumphs for the Obama administration and not disastrous missteps.

“The irony of the Obama years,” Rhodes mused, “is going to be that he was advocating an inclusive global view rooted in common humanity and international order amidst this roiling ocean of growing nationalism and authoritarianism.” Got that? “Inclusive” and “common humanity” on one side versus “nationalism” and “authoritarianism” on the other.

This is not politics in any ordinary sense. It is a resurgent Manichean dualism in which the elect battle the infidels (despite the irony that the elect in this case are not elected). All is not lost, however, for if Rhodes is right, the rising generation “seems to share a very Obama view of the world.” It’s just that there are “retrenchment forces pushing back from the other direction who have actually gotten their hands on the levers of power now.” Imagine that!

The fascinating thing of “The Final Year” is the glimpse it affords into the engine room of a certain species of elite bureaucratic presumption. It is earnest, articulate, educated, well-meaning, and utterly, dangerously naïve. When you review the series of foreign policy disasters over which Obama presided—the names Libya, Syria, and Iran offer a good start—and then contrast it with his warmhearted rhetoric, you begin to understand why Graham Greene could warn that “innocence is like a dumb leper who has lost his bell, wandering the world, meaning no harm.”

What we have on view here is a super-Whig interpretation of history, a sort of Émile Coué approach to world affairs: “Tous les jours à tous points de vue je vais de mieux en mieux.” “Every day in every way I am getting better and better.” History may not always proceed in a straight line, Obama admits at one point; it may zig-zag. But the general trend, he insists, is “ultimately towards a less violent, more empathetic, more generous world.” Coué could not have put it better.

The breathtaking presumption of virtue, the unshakeable confidence in one’s moral election, is patent throughout this documentary. It is also vividly on view in a New York Times story from a couple of days ago about Obama’s reaction to Donald Trump’s triumph in the 2016 election: How Trump’s Election Shook Obama: ‘What if We Were Wrong?’. The irony in the title is that no one involved in the story, not Obama, not Ben Rhodes, not the Times reporter seriously entertains the question “What if we were wrong?”

Yes, Obama wonders whether “we pushed too far.” “Maybe,” he says, “people [though not, of course, his people] just want to fall back into their tribe.” But there is no suggestion he might not think he is traveling in the vanguard of history. “Sometimes I wonder whether I was 10 or 20 years too early,” he said. If only the world were elevated a little higher towards my plane of enlightenment, then people like me would still be in power and all would be right with the world! Amazing.

Meanwhile, back in the real world, official unemployment is down to 3.8 percent (real unemployment is 7.6 percent and falling), black unemployment is at an historic low, the economy is buzzing along, consumer confidence is the highest it’s been in a generation, North Korea is headed to the bargaining table, Iran’s efforts to get nuclear weapons is being starved, and preposterous virtue-signaling and prosperity blighting climate change pacts have been put where they belong, on the ash heap of history. Slowly, slowly, at least parts of the soft-totalitarianism of the administrative state are being peeled back and the fresh breezes of local control and individual responsibility are making a come back.

In his book Utilitarianism, John Stuart Mill said, “as between his own happiness and that of others, justice requires [everyone] to be as strictly impartial as a disinterested and benevolent spectator.” The great Victorian polemicist James Fitzjames Stephen treated this idea with some of the contempt it deserves. “If this be so,” Stephen wrote, “I can only say that nearly the whole of nearly every human creature is one continued course of injustice, for nearly everyone passes his life in providing the means of happiness for himself and those who are closely connected with him, leaving others all but entirely out of account.” As Obama might put it, nearly everyone want to fit back into his own tribe. But this, Stephen argues, is as it should be, not merely for prudential but also for moral reasons.

The man who works from himself outwards, whose conduct is governed by ordinary motives, and who acts with a view to his own advantage and the advantage of those who are connected with himself in definite, assignable ways, produces in the ordinary course of things much more happiness to others . . . than a moral Don Quixote who is always liable to sacrifice himself and his neighbors. On the other hand, a man who has a disinterested love of the human race—that is to say, who has got a fixed idea about some way of providing for the management of the concerns of mankind—is an unaccountable person . . . who is capable of making his love for men in general the ground of all sorts of violence against men in particular.

The habit of moral infatuation is a hardy perennial. With Barack Obama, we witnessed a veritable infestation of the species. A lot of people criticize Donald Trump not only for his lack of refinement but also for his imperfect morals. “The Final Year” quietly dramatizes a bleak alternative in which genuine refinement is coupled with unabashed moralism. (It is worth noting that one element that the film neglects is the raw appetite for power, but we may leave that to one side.) It is not, I think, an appealing portrait, though as I say it is unclear if that was the filmmaker’s intention.

Photo credit: Stephane Cardinale – Corbis/Corbis via Getty Images