One thing I love about my neighbors is that my association with them is premised on shared immediate interests rather than the abstract self-interests that permeate contemporary identity politics. I’ve never had a sign endorsing a political candidate on my lawn. I’ve never had a political bumper sticker on my car. In my mind, the political struggle is irrelevant to my relationship with my neighbors.

Sadly, however, it seems that more and more of my Houston neighbors think the political issues animating the national discourse are germane to daily life and interaction in our tiny corner of the city.

In a nation of hundreds of millions of people spread over millions of square miles, the neighborhood is the foundation of civic life in America. On the national level, the relationship that we share with our fellow citizens is mostly an abstraction: gaining a full sense of “We the People” is uniquely difficult in a diverse society of 350 million of them.

And yet, our republic calls upon us to consider the needs of all Americans in our political processes—even people we will never meet and those with whom we can expect to have little in common. How does one stay committed to that responsibility when the collective no longer seems to recognize any shared interests, values, or experiences?

Good Neighboring

I believe that the answer lies in good neighboring.

Our neighborhoods are the concrete reality that serve as the model for interaction in the abstract space of the larger society. Unlike the voices that I engage with in the public sphere, I occupy physical space with my neighbors. As a result of our proximity, we share many interests. Everyone works to keep our neighborhood attractive because the value of each home is dependent on the condition of the ones around it. We keep an eye out for children from other families because we know they are friends with our children—and we know that the risks and dangers faced by their children also confront our own. I look out for my neighbor’s property not only because he is my friend, but because I anticipate reciprocation.

Yard signs for political candidates have a long history in the suburbs, but the past few years have brought with them political signs that do little more than disparage the general political outlook of others. Whereas yard signs used to pop up only in the month or two before an election, walking around the neighborhood is now a political experience year-round.

It started in earnest after Trump’s election, with signs reading, “All are welcome” or “Hate has no home here” (often written in various languages with the English translation in smaller type near the bottom) became common.

These signs would come and go—relegated to the garage, then virtuously hauled back out whenever Chuck Todd found something new to be especially furious about. I imagine that the homeowners with the signs view them as an expression of tolerance and friendship, but they are also an implicit smear—a smear, I suspect their owners intended.

In saying that hate has no home in their house, they suggest that it does have a home in some of their neighbors’ houses. In saying “all are welcome” in their homes, they suggest that not everyone is welcome in the homes of others. In short, they accuse their neighbors of being bad people.

But what does a “welcoming” home consist of? What are the “signs of hate” (pun intended)?

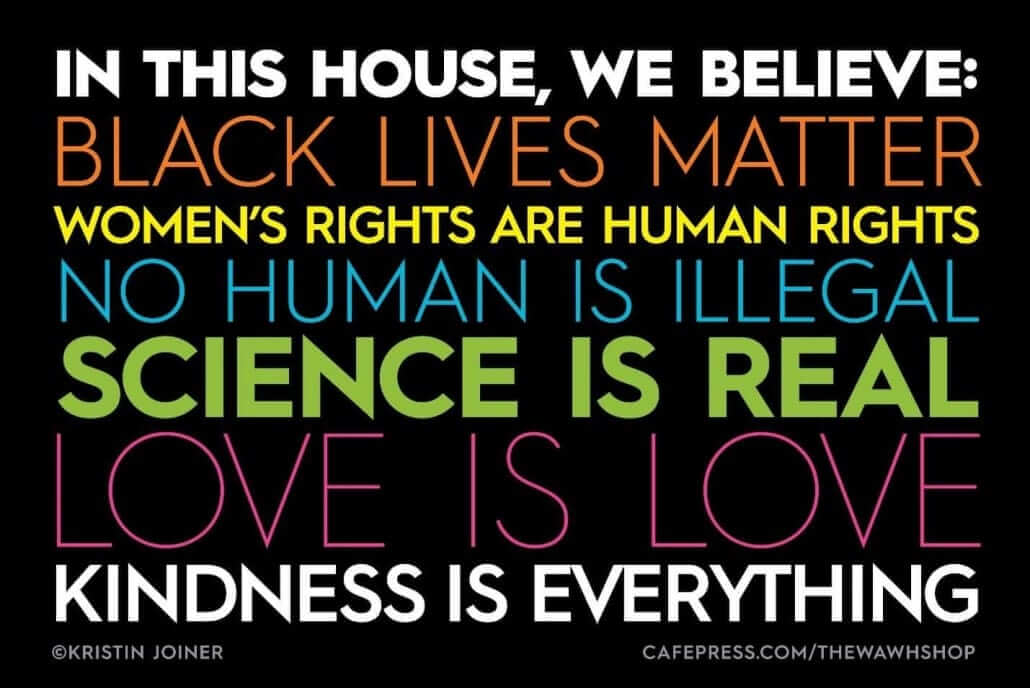

In the aftermath of George Floyd’s death and the ensuing protests and riots, a sign that I had seen a few times before suddenly multiplied like mushrooms in the spring:

As a number of other commentators have demonstrated, such signs are clear expressions of the residents’ disdain for their political opponents. In most cases, these opponents are their neighbors. Thus, we see what makes a home “welcoming” or “hateful”: if you agree with the worldview of the progressive Left and the homeowner, you are a virtuous person. If you don’t, you’re obviously a terrible neighbor.

The sign above is an implicit statement of hatred couched and (barely) concealed in a rhetoric of benevolence and inclusion. Further, the placard willfully misrepresents the beliefs of the homeowner’s opponents. From the top of the sign to its bottom, its claims are disingenuous responses to straw men. I will take them one by one.

Black Lives Matter

In saying that in their house “Black Lives Matter,” these sign bearers imply that those lives don’t matter to my family and other neighbors. But black lives do matter to my family and our friends. We were deeply dismayed by the unnecessary deaths of black people like Arbery and Floyd. Nevertheless, we do have major reservations about the stated goals, assertions, and hypocrisies of the organization called Black Lives Matter.

In the uncompromising minds of those who placed the sign, however, our reservations are prima facie evidence that “hate” “has a home” at my house. The proposition on the sign allows for no gray area, no debate, no middle ground. You accede to the claim or you’re a racist. This stifles any neighborly dialogue. In presenting me with those two choices, the homeowners effectively have said they don’t want to talk to me.

Women’s Rights Are Human Rights

Honestly, I’m not even sure what this one means. It advances a claim with which virtually no one would disagree. Any rational person would agree that women are humans, and as such, they have the same rights as any other human. Of course, the proposition is actually a litmus test for the reader’s position on the mythical gender pay gap or women’s “right” to have an abortion.

But again, the sloganeering disallows any nuanced discussion. What about those who believe that a fetus is also a human, and as such, has the rights (including the right to life) that any other human would have? What about people who suggest that the “pay gap” between men and women is attributable to factors that have nothing to do with discrimination? These are conversations the homeowner is simply unwilling to have. He’s right, and I’m wrong (and thus, a bad, “unwelcoming,” “hateful” neighbor).

No Human Is Illegal

This one is simply ludicrous. Obviously (right?), the mere existence of any person is not illegal. When I hear someone say “no human is illegal,” I always ask “Are any drivers illegal?” The answer, clearly, is of course. When an unlicensed person is ticketed for being an illegal driver, we aren’t saying their existence is illegal—we’re saying their driving is. The same goes for an illegal purchaser (perhaps in the case of the underaged) of alcohol. With the phrase “illegal immigrant,” we are not saying the person is illegal, we are saying that he or she illegally undertook some action—in this case, immigration.

This is not a complex idea, and the owner of the sign either pretends he cannot understand this distinction or assumes I am too stupid to see this rhetorical sleight of hand. Either way, he is not being very neighborly.

Science Is Real

Somehow, this one is even more ludicrous than the last. There is actually no one saying that science isn’t real. The fact that the homeowner apparently thinks his unwelcoming, hateful neighbors believe this demonstrates his total failure in trying to get to know them. Yes, science is “real.” It is one tool among others for understanding the world. But it is a necessarily limited tool and one that has often been factually wrong. Further, history shows many times that “science” has been factually correct, and morally wrong.

The people that the homeowner intends to provoke have no doubts about the reality of science—instead, they are (rightly) concerned with the agenda-driven aims that determine which scientific projects are pursued and funded, which scientific findings are offered to the public, and which ones are not. The residents attempt to belittle their neighbors—by pretending the reality of science is at issue, they assume the posture of a knowledgeable parent over a recalcitrant, ignorant child. Like you, I don’t appreciate my neighbors calling me stupid—especially when they do so accusing me of holding beliefs that I don’t actually hold.

Love Is Love

I can only assume this is a commentary on LGBT issues. But I have never encountered anyone who has argued that committed same-sex or intersex couples don’t love each other. The slogan is a tautological over-simplification of the complex legal issues underlying the LGBT agenda so as to avoid any actual dialogue with their unwelcoming, hateful neighbors.

There was never any question about the authenticity of love, it was about what sorts of relationships will be formally recognized and endorsed by the state, and which sorts of rights and obligations extend from those endorsements. The family with the sign in the yard has those questions solved. No good faith disagreement is possible. They clearly have no choice left but to shame you as you pass on your bicycle.

Kindness Is Everything

I won’t dwell on something this insipid. Generosity isn’t “everything.” Pity isn’t “everything.” Nothing is “everything.”

That much is clear, even to the homeowner: if “kindness” was “everything,” what kind of jackass would put a sign in their yard that denigrates the values of his neighbors?

The Fate of the Neighborhood as the Fate of the Nation

If I can’t count on the guy five doors down to recognize that our mutual interests transcend our voting tendencies, what hope do I have that my fellow citizens around the country will do so? The prospects are pretty poor. The past few months have shown that the people and institutions driving the national unrest only recognize shared interests based on pre-existing ideological commitments. Their signs drive this point home, telling me up front that our interaction must be entirely on their terms. Anything short of that simply means we can’t be friends. Their yard signs tell me they don’t want me as a neighbor.

It is important to note that while I do see the occasional signs endorsing Trump or other conservative candidates, I have yet to see any signs that belittle left-leaning members of our community for their political perspectives in a general way (though they do exist).

This is a testament to the conservative commitment to the local. How we treat our neighbors is the template for how we treat our fellow countrymen. Remaining dedicated to the neighborly treatment of our neighbors (especially those who disagree with us and make us objects of their mockery) will help us to retain the moral high ground as the battle over the future of America intensifies. Further, it reminds our children that the imperative to love our neighbors supersedes politics.

So, what to do with neighbors bent on dividing the community with such signs?

Ignore them? To do so would only intensify our isolation. Kick down their signs? No, that’s what they want—it would validate their belief that every street is full of haters and bigots. Explain to them that their signs are off-putting and demonstrate how they misrepresent their opponents’ positions? No: dedication to the leftist worldview has much more in common with religious fervor than rational belief, so you aren’t going to change their minds.

All you can do is help them change their mind about you by showing that you are a welcoming, loving person despite your difference of opinion. In short, the hope for a neighborly community (and, by extension, a healthy civic life) lies in calling our opponents to live up to their own rigid values of tolerance and diversity. There are many ways we are working to fix our nation. But that project is doomed to fail if we don’t also work on fixing our neighborhoods. If you haven’t already done so, introduce yourself to the guy with the sign.