Anyone who worries today about the cultural assimilation of immigrants quickly meets with what I call the Irish Retort: “People used to worry that the Irish wouldn’t assimilate, and they turned out just fine, so today’s immigrants will too.” Immigration restrictionists usually respond, correctly, that America has changed over the past 100 years in ways that make it less conducive to assimilation, including the rise of multiculturalism as a governing ideology.

As I explained in my recent Natcon speech, however, there is a second and more powerful response to the Irish Retort, which is that the Irish did not fully assimilate. Neither did the Germans or the Poles or any other immigrant group. All of them retained some characteristics of the Old Country, indicating that culture is more persistent than Ellis Island lore would have us believe. If yesterday’s immigrants changed American culture in the long run, then today’s immigrants surely will as well.

A new book called The Culture Transplant makes this case much better than I can. The author is Garett Jones, a George Mason University economist who has spent much of his career pondering why some nations are more successful than others. He reviews the literature showing that the variance among immigrant groups in certain values—such as trust, frugality, and personal responsibility—persist through multiple generations of their descendants.

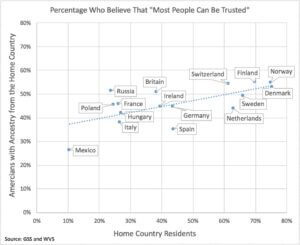

The figure above provides one example of that persistence. (This figure is based on my own calculations, but it’s similar to one that appears in the book.) It shows a strong correlation between the level of social trust among American ethnic groups on the vertical axis and the level of social trust in their ancestral countries on the horizontal axis. For example, in Europe Swedes are more trusting than the Irish, who are themselves more trusting than the Italians. Remarkably, despite 100+ years of opportunity for assimilation, those three ethnic groups order themselves the same way in the United States.: Swedish Americans are more trusting than Irish Americans, who in turn are more trusting than Italian Americans.

That Americans of European descent remain such a heterogeneous group is striking. In fact, the historian David Hackett Fischer has shown that American settlers from different parts of a single European country, England, exhibited cultural divisions that persist to the present day. Places in the United States settled by Puritans, for example, are notably different today than places settled by the “Scotch-Irish” borderers.

Cultural persistence matters, Jones says, because culture undergirds wealth-creating institutions. So when people move to a new land, their previous institutions tend to follow them. “If you’re trying to guess how rich a country is today, you’ll make a far more accurate guess if you know the history of the people rather than the history of the place,” he writes, with my emphasis added. The familiar example is North America, which was transformed by Western European settlers, but the relationship between people and prosperity holds in the Old World as well. In fact, Jones emphasizes how successful the Chinese Diaspora has been in Southeast Asia.

Although not discussed much in the book, another example of the connection between culture and economic performance is the experience of Mexican Americans. As an outlier in the figure above, they exhibit a low level of social trust reminiscent of Mexico itself. It is probably not a coincidence that Mexican Americans have also struggled to reach economic parity with other groups in the United States. My recent analysis of the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth shows that the grandchildren of Mexican immigrants are only half as likely as the grandchildren of European immigrants to earn a bachelor’s degree, and their test scores and incomes continue to lag behind as well.

The Jones thesis of cultural transplant devastates the starry-eyed “come one, come all” immigration advocacy popular among progressives and libertarians. It shows that the importation of cultures that are not historically conducive to prosperity is a serious weakness of our current immigration policy. The result could be lower quality governance, decreased trust, less support for free enterprise, reduced innovation, and many other effects large and small. These effects cannot be dismissed with nostalgic references to the Irish of yesteryear.

Furthermore, Jones argues that it is not merely self-interest that should make the United States leery of mass immigration. As one of just a handful of countries responsible for the vast majority of innovation in the world today, the global economy would suffer if U.S. institutions become less hospitable to new ideas and technologies. In fact, Jones says that we should have an “obsession” with making sure the most innovative countries stay that way. The implication is that immigration could weaken not only the United States, but perhaps the world as a whole.