Rush Limbaugh died a year ago today, on February 17, 2021. It seems a fitting occasion to remember, in good humor, philosophic levity, and political gravity some of the highlights of his remarkable American life.

James Golden (known fondly to Rush’s millions of listeners as Mr. Bo Snerdley) was with “The Rush Limbaugh Show” for three decades, serving as call screener, “official program observer,” producer with the show’s guest hosts—and much more. He tells many good Rush stories in his new book, Rush on the Radio: A Tribute from His Sidekick for 30 Years, and countless others in hours of episodes of a podcast he launched, conversationally documenting the tale of Rush’s life and career with colleagues, friends, neighbors, and family. Zev Chafets’s biography, published in 2010, is also worth a read. I call Limbaugh “Rush,” not out of presumptuous familiarity, but because that is how his listeners lovingly knew him, and he loved them as much as they loved him.

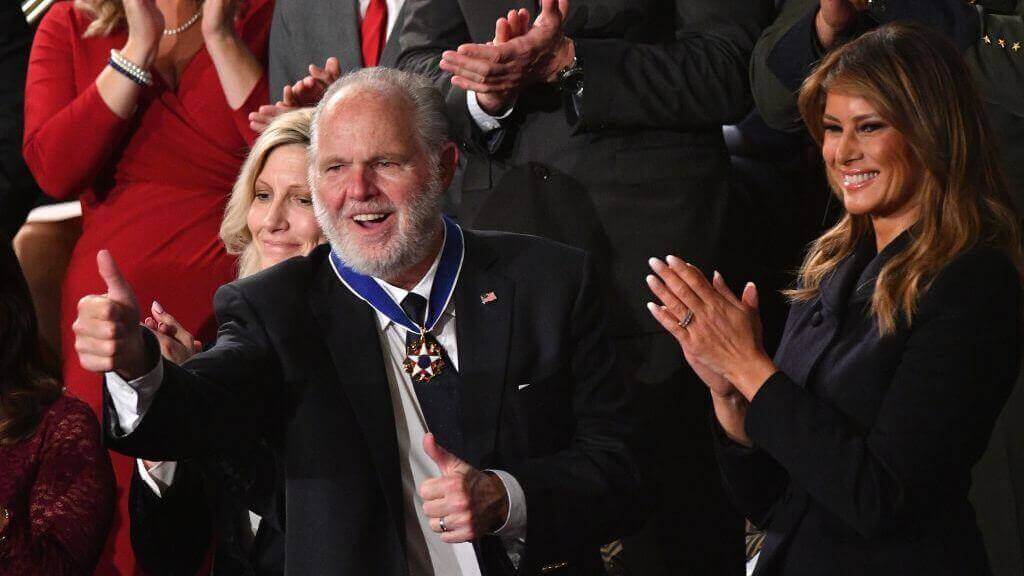

On February 3, 2020, a year before he died, Rush announced to his radio audience that he had been diagnosed with advanced lung cancer. A few days before that, President Donald Trump had called Rush and insisted that Rush and his wife Kathryn come to Washington on February 4 as his guests at the State of the Union Address. There, before a joint session of Congress in the nation’s capital, with Rush and Kathryn sitting next to the first lady in the gallery, the president interrupted his speech to say, “Rush Limbaugh, thank you for your decades of tireless devotion to our country,” and, with other compliments and expressions of gratitude, he awarded him America’s highest civilian honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

James Golden recalls how “[i]n the days that followed, accolades poured in, as did the hysteria from the left. I have to tell you, I enjoyed reading and watching it all. The left were beside themselves. How dare this president give Rush Limbaugh the Medal of Freedom, and how dare he present it on this special night?!” Golden later reflected, “only President Trump could do this. Only he could give Rush the highest civilian honor in America, and make sure almost every elected Democrat attended the ceremony” [Italics in original]. In his years of working with Rush, Golden had learned that if you’re driving liberals to hysteria, you’re probably doing something worth doing.

Rush Limbaugh ruled America’s airwaves for 33 years, working practically up to the day of his death. On behalf of the mythical Excellence in Broadcasting Network, from behind his golden EIB microphone, in his “prestigious Attila the Hun Chair” at the “Limbaugh Institute for Advanced Conservative Studies,” El Rushbo—the all-knowing, all-caring, all-feeling, all-sensing, all-concerned, all-everything Maha Rushi, “epitome of Morality and Virtue,”—broadcast three hours a day, five days a week, 50 weeks a year, from 1988 to 2021, “having more fun than a human being should be allowed to have.”

He was an “instrument of mass instruction,” on “the cutting edge of societal evolution,” joyously spreading “across the fruited plain” analysis and opinion “documented to be almost always right, 97.9 percent of the time” by the Sullivan Group. Beginning in the last year of the Reagan Administration and continuing to the final days of the Trump Administration, Rush was the most influential voice of conservatism, and then postconservatism, in America. His audience—the many millions of America-loving “ditto heads”—anticipated and became the soul of the MAGA movement that Donald Trump galvanized and that remains the most vibrant force for freedom in the country.

As Zev Chafets writes, “It is hard to describe how transgressively original Rush Limbaugh sounded” in the media environment into which he launched himself. When he began, nothing you could find on broadcast radio networks in America sounded like him. No one would dare broadcast mockery of sacred liberal pieties in such an “irreverent tone.” Hearing Rush on the radio for the first time was like seeing Elvis on TV for the first time, as if you were “witnessing something completely different and possibly even dangerous,” something bold, independent, and subversive. (Patriots young and old take note: your country needs your boldness, independence, and these days especially your subversion.)

Rush was as an original, exuding all the over-the-top, red-blooded American bravado and joy of young Elvis belting out “You ain’t nothin’ but a hound dog!” or of young Cassius Clay declaring to the world, “I am the Greatest!” One essential ingredient of Rush’s genius was his gift for inviting America to laugh with him and at him, as they laughed at themselves and the absurdities of the world—but especially, and subversively, at tyrannically sacred liberal pieties.

Here’s one version of Rush’s standard introduction:

Greetings, conversationalists across the fruited plain, this is Rush Limbaugh, the most dangerous man in America, with the largest hypothalamus in North America, serving humanity simply by opening my mouth, destined for my own wing in the Museum of Broadcasting, executing everything I do flawlessly with zero mistakes, doing this show with half my brain tied behind my back just to make it fair because I have talent on loan from . . . God. Rush Limbaugh. A man. A legend. A way of life.

On a given day, you might then hear the Rush Hawkins Singers (also known as the Black Lives Matter Singers) singing the great gospel hit, “Thank the Lord Rush Limbaugh’s On.”

Rush Hudson Limbaugh III was born on January 12, 1951, in Cape Girardeau, Missouri, a hill town just a couple of hundred miles down the Mississippi from Mark Twain’s hometown of Hannibal. Rush knew he wanted to be in radio from the time he was eight years old. As his mother described him, “He just didn’t seem interested in anything except radio.” In Rush’s words, “In the mornings getting ready for school I’d hear the guy on the radio, and he just sounded free and happy, like he was having a wonderful time. That’s what I wanted, too.”

Radio, to the young Rush, was something like what steamboats were to the young Mark Twain. He dreaded school as much as Huckleberry Finn did—it was like “prison” to him—and he left it as soon as he could. He started work as a DJ (calling himself “Rusty Sharpe”) at a small station in his hometown when he was 16. He dropped out of college after his first year, in 1971, and left Cape Girardeau for a job as a DJ, under the name “Bachelor Jeff” Christie, at WIXZ-AM, a Top 40 station in McKeesport, Pennsylvania. Some clips of his show there are still floating around, and the rhythms, attitude, and tone of his voice are immediately recognizable.

As Rush often told the story, he toiled away in obscurity and penury for 17 years, getting fired several times, and sometimes going broke (He earned $18,000 in 1983), before he got his “big break” and became an overnight sensation at Station KFBK in Sacramento in 1984, under his own name, just being himself, doing radio the way he dreamed of doing it.

A few years later, he moved to New York and, amazingly quickly, made himself famous as the greatest broadcaster in radio history. On August 1, 1988, he went national from WABC in New York, syndicated to 56 radio stations reaching something like 250,000 listeners; within two years, “The Rush Limbaugh Show” would be airing on more than 600 stations, with up to 27 million “ditto-heads” listening weekly. As James Golden writes, “The program changed talk radio and rescued the AM radio industry. Before Rush’s national program, there were less than two hundred stations in the United States with a ‘news talk’ format. Twenty years later, there were over two thousand.”

When Rush started in 1988, the national media were basically the three networks, CNN, and the New York Times and Washington Post. These liberal media spoke authoritatively as the voice of objectivity. One of Rush’s greatest accomplishments was discrediting this authority and demonstrating that these liberal elites, presenting their partisan ideology as objective and unquestionable truth, did not speak the truth and did not speak for the American people. They hated him passionately for revealing that.

By 1990, Rush had so many listeners the national media could not ignore him. Ted Koppel hosted him on “Nightline” and said, “There is absolutely no one and nothing else out there like him, anywhere on the political spectrum.” Rush’s first book, The Way Things Ought to Be, published in 1992, sold more than 1 million copies and remained atop the New York Times best seller list for several months.

After Bill Clinton took office as president in 1993, Ronald Reagan wrote Rush, saying that Rush had become “the number one voice for conservatism” in America and thanking him for all he was doing “to promote Republican and conservative principles.” Hollywood celebrities, liberal politicians, and the “drive-by media” (later to become the “state-controlled media”) were already comparing Rush with Hitler, so he knew he was rolling. From the moment Clinton took the oath of office, Rush began to open his shows with “America Held Hostage, Day One,” and he continued to count the days.

When Republicans won majorities in both houses of Congress in 1994 for the first time in 40 years, Rush was given much of the credit for the stunning victory and was made an honorary member of the freshman class of the 104th Congress. Just before those historic midterm elections, Rush received another letter from Reagan. It read in part: “I am comforted to know that our country is in the capable hands of gifted young individuals like you and your listeners. You are the backbone of our great nation.” It was signed “Ron.” Rush never met Ronald Reagan, but he had long ago anointed him “Ronaldus Magnus, the greatest president of the 20th century.”

But Rush was not an activist. He thought of himself as an educator, and he was very serious about his work. As he told Golden in 2008, “Elected officials come and go; my success does not depend on who wins elections. Theirs is a different business than mine.”

Sometimes Rush just described his show as the “relentless pursuit of the truth,” and he conducted that pursuit like a Socrates of the airwaves, dialectically, with Bo Snerdley and a host of interlocutors from the EIB family and callers with all kinds of opinions, three hours a day for 33 years before an audience of millions.

Mark Steyn remembered the first time he ever heard Rush: “It was a unique combination—absolute piercing philosophical clarity, and a grand rollicking presentational style.” Longtime friend Mary Matalin said that long after Rush was gone, fair-minded historians would regard him “as a pivotal, transformational Socratic-type” figure. Go ahead, laugh—Rush would join you and offer you an expensive cigar.

In deadly seriousness, though, Rush—the “Doctor of Democracy,” “America’s Truth Detector”—offered daily analysis of the human condition more intellectually probing and substantial than the best efforts of the most revered and prestigious intellectual in America today—“Professor of Antiracism,” “Raja of Reconciliation,” Ibram X. Kendi—or any of the tens of thousands of his woke tenured colleagues; and the fabled “Limbaugh Institute for Advanced Conservative Studies” offered a daily civic education immeasurably better than any offered today by the most elite and expensive universities in the land.

Maybe even more significant, in place of the grim, tight-lipped, tyrannical liberal piety that is the required institutional, moral, and intellectual disposition in every elite university, Rush offered generous helpings of liberating laughter. The source of the liberation and the laughter was his independent-minded subversive Socratic-American investigations of the world.

Rush was serious about politics, and what enabled him to be as serious as he should be, was his understanding that there were things more important than politics. Good politics established the conditions for higher things: for freedom of thought, freedom of religion, the flourishing of art, music, literature; the happiness of husbands and wives and fathers and mothers and children in families; the joy of sports of all kinds and of watching sports with friends and rooting for one’s team. Rush’s seriousness, good humor, and joy were direct products of his understanding and appreciation of the freedom to pursue happiness that good politics makes possible.

This is precisely why every pious liberal is miserable and spreads his liberal misery wherever he goes: because for the pious liberal there is nothing beyond politics. Everything is about power and is reducible to power. As the world has seen with shocking clarity these past two years, the pious liberal will not rest until he controls your every thought, word, and deed. He wants to tell you how to worship God, manage your personal health, and raise your children. In fact, as the enforcer for a brutish state, he will close down your church, force needles into your arm, and take your children from you. He won’t let you play football, baseball, or tiddlywinks unless you pervert your sport into a ghastly hosannah to liberal nihilism. And this is also (here I permit myself a moment of Rush-like optimism) why the pious liberals will always fail—after they have spread as much of their liberal misery as they can: because human beings by nature pursue happiness, and they always will.

Rush’s relentless pursuit of the truth was animated by a combination of reverence and irreverence: reverence for the true and good (especially the truth that made America good) and irreverence for all those authoritative poses and prejudices that get in the way of the truth and the good. This reverence and irreverence were generously seasoned with piercing wit and high spirits, and with the profound Aristotelian insight made famous by Harry Jaffa via Barry Goldwater: that extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice and moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue. When Rush called you a “moderate,” he meant it to sting.

After 20 years of doing his national show, by the time William F. Buckley died in 2008, Rush knew that he was “the intellectual engine of the conservative movement.” By this time, Rush was so important that Obama and his incoming administration treated him as the leader of the Republican Party. A few days after taking office, Obama invited Republican congressional leadership to the White House for a “summit” to demonstrate the “bipartisanship” he had on offer. He opened the summit by telling his Republican colleagues: “You can’t just listen to Rush Limbaugh and get things done.” Of course, lots of “moderate” Republicans felt the same.

In a keynote address to the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) in 2009, Rush explained his conservatism. When conservatives look at the country, he said, “We see Americans. We see human beings. We don’t see groups. We don’t see victims.” His conservatism was defending the freedom, interests, and sovereignty of the American people, and he saw that the greatest challenge to doing this was the liberal identity politics of what was once called political correctness and came to be called wokeness. As he said on another occasion, “We are in a battle for the . . . kind of country this is going to be. We’re not in a battle over who is going to win every four years. . . . The battle we are in is . . . literally . . . about [the question] will this remain the United States of America as founded.”

The morning after Rush gave that CPAC keynote address, Obama’s Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel said on “Face the Nation”: “Rush Limbaugh is the voice and the intellectual force and energy behind the Republican Party.” But it had long been apparent to Rush that “moderate” or establishment Republicans were unwilling and unable to fight the battle that was needed to save the country. He just couldn’t figure out why, until he read one of many important writings by the late and lamented Angelo Codevilla, an old friend of mine, a good friend of American Greatness, and a representative of what came to be thought of as the Claremont school of thought.

Browsing through the July 2010 issue of The American Spectator, Rush ran across Codevilla’s long essay “America’s Ruling Class.” It struck him so strongly that he spent most of an entire show reading and discussing it with his listeners. The essay clarified for him something he had been “struggling to explain for 20 years,” namely, why Republicans never fight the fight that we need to win. The answer Codevilla showed him was that establishment Republicans want to belong to the ruling class, and it doesn’t matter to them that the ruling class is run by liberal Democratic nihilists. What matters to them, what they will sell their souls and their country for, is to be part of the club. Rush later wrote an introduction for Codevilla’s book arising from that essay. And the “Limbaugh Institute for Advanced Conservative Studies” continued to build on Codevilla’s Claremont-school analysis.

Rush’s policy was generally never to endorse a candidate in the primary season. Like many conservatives, Rush was a Ted Cruz supporter going into the Republican Party presidential primaries in 2015-2016. He praised Donald Trump for inspiring a movement, but for those of his listeners who were ideological conservatives, he said, as late as February 2016, Cruz was their man. Trump, as he rightly said, was not “ideological.” But after Trump’s win in New Hampshire, Rush expressed his interest on air: “[I]t’s tempting and it’s exciting to think that a revolution’s going on, but I’m not so sure.” He became more sure, and he joined and advanced the revolution, after reading another essay, “The Flight 93 Election,” which he found at the Claremont Institute website, by another old but younger friend of mine, and a dear friend of American Greatness, Michael Anton, then writing and expanding the Claremont-school horizon under the nom de guerre, Publius Decius Mus.

On September 7, 2016, Rush devoted most of his show to reading and discussing Anton’s essay, and he explicitly compared the quality of its thinking and the character of its analysis to the earlier Codevilla essay. “The piece is so good. It is just a home run, every paragraph. . . . Folks, this is on a par with Dr. Angelo Codevilla’s ruling class versus country class piece from The American Spectator a few years ago.”

He continued: “And the reason this piece appeals to me is [that] it validates so many of the instincts that I have had over the years . . . and that I’ve shared with you about what is happening to the conservative movement and how conservatism’s being defined, and who seeks to define it and what it means going forward.” The piece is “a shaming of the conservative intellectuals that comprise the NeverTrump movement.”

Rush sums up the argument: if you’re a conservative, and “if you’re really serious about how bad things are but you can’t find [it in] yourself to oppose Hillary Clinton, then you’re worthless. That’s what this is essentially saying, but in 10 pages. It’s great.”

Rush’s reading and discussion of Anton’s essay on his show was indispensable to making the essay the most influential essay of the 2016 election, a defining essay in modern American politics.

To his last days, Rush and The Limbaugh Institute continued to develop this Claremont-school postconservative analysis of the American crisis. On October 13, 2020, just three months before he died, Rush urged his listeners to watch a 17-minute speech: “Trump 2020: A Man vs. a Movement,” by Claremont Institute Board Chairman Thomas Klingenstein, which, thanks to Rush, got over 1.5 million views on YouTube.

As Rush put it:

I’d like you to find 17 minutes you can spend uninterrupted and listen to this video from the chairman of the board of the Claremont Institute. . . . It’s nothing flashy. It doesn’t have massive production values. It’s nothing like that. It’s just one man and his legitimate reasons for Trump and his deadly . . . fear of what this country faces if Trump loses. . . . I’ve watched it a bunch of times. In fact, you will note as you watch this that I have lifted a couple of things from this video—just a little, just a few things. It is that good. . . . One of the most fascinating things that Mr. Klingenstein points out, is . . . that in normal times he wouldn’t even think of voting for this man. Now, don’t take that as a negative. Do not think you’ve got a NeverTrumper here who’s changed his mind. It’s not that at all. He’s just being honest with you.

He, in fact, says that in these times, Donald Trump is the only man who can save this country, is the only man who can do what is necessary to preserve the American way of life. . . . He’s . . . scared to death like we all are, and he explains why Trump is the only person that has a prayer of saving America.

On December 9, 2020, Rush said on his show what Codevilla and other Claremont-school thinkers had been saying: “I actually think that we’re trending towards secession.” Without naming names, he referred to many commentators who had already concluded that “It can’t go on this way. . . . There cannot be a peaceful coexistence of two completely different theories of life, theories of government, theories of how we manage our affairs. We can’t be in this dire a conflict without something giving somewhere along the way.”

As Rush said on the air frequently, he wasn’t concerned about what happened to the Republican Party or even to “conservatives.” He was concerned with what was happening to the country. And when he talked about what it was that distinguished America as a country and made it worthy of concern, Rush talked the way the Claremont school has been talking from the beginning: “What is it that sets us apart? . . . and there is one answer, and it is found in the Declaration of Independence. We are all endowed by our Creator with certain unalienable rights. . . .” Because of this, America “became the greatest nation in human history.”

In the concluding episode of his memorial podcast, James Golden invited Larry Arnn to share his recollections of Rush. Larry, another old friend, one of the Claremont Institute’s founders, currently president of Hillsdale College, got to know Rush in Sacramento back around 1987 and told him back then how much he liked his show. In addition to Rush’s genius as a performer, Larry reflects, “he represented some big things that are rooted deeply in America, and he defended those things consistently for his whole career. And, of course, those things cannot die. They are eternal. He has helped to sustain them so far. And we should carry on.”

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this article misidentified Rush Limbaugh’s honorific for Ronald Reagan. It was “Ronaldus Magnus,” not “Ronaldus Maximus.”