There are many significant moments in American history that have informed the principles of America’s tradition of liberalism, but not since the American founding have we lived in one so important. The United States is at a “1776 Moment” of ideological transformation. The American Revolution of 1776 marked a change of political ideology from constitutional monarchy to liberalism. Today, the ideological transformation is from liberalism to progressivism.

Like its antecedent, our “1776 Moment” was decades in the making. Unlike its predecessor, it is more like a putsch or revolution from above, where a progressive elite first targets and then replaces a liberal one. The consequences are dramatic: the truths of 1776 have become the crimes of 2022. What has occurred over the last generation should be considered a revolution, even if it is too soon to tell whether it is a successful and lasting one.

The American Ideology of Liberalism

Historically, the United States has possessed a single dominant ideology of liberalism that sustained itself against previous ideological challengers, from the agrarian Toryism of the American South in the 19th century to the socialist or fascist challenges in the last. Liberalism is a political ideology that promises liberty for the individual. It employs the concept of inalienable rights and individual freedoms. These ideas and principles are expressed in America’s founding documents: the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights, as well as in Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, and have been echoed in American political ideas, practices, tradition, and culture since the American Revolution of 1776.

U.S. political institutions encompass liberal principles, values, norms, and culture. These include the ideas that animate liberalism—freedom, private property, respect for the rule of law, citizenship, and patriotism—and thus the country’s formal political institutions.

For liberalism to work, the power of government must be controlled. It is limited, first, through the separation of powers, as advocated by Montesquieu, into what we now term an executive, legislature, and judiciary as separate and co-equal branches of government. Federalism offers a second avenue to check the concentration of power in a central authority by assigning some political power to states, counties, and other local governments. Third, periodic popular elections further serve as a bulwark against encroaching governmental power, as does a culture of respect for the rule of law.

Observers from Alexis de Tocqueville to American political theorist Louis Hartz saw that America’s liberalism anchored the political system and made it immune from its ideological challengers and thus ideological unrest. In the American context, while “liberals” and “conservatives” had their policy differences, both camps were classically liberal in their general outlook. Other ideologies, such as socialism, arose out of foreign philosophies and experiences that were alien to the American experience. British political and economic historian Sir William Ashley captured the point well in his study, Surveys Historic and Economic, published in 1900, in which he identified the importance of the lack of a feudal experience: “As feudalism was not transplanted to the New World, there was no need for the strong arm of a central power to destroy it.”

America’s history and liberal ideology proved to be fortuitous for the rise of this great country. To be sure, there were other factors, like good fortune, that assisted America’s success. This included the abundance of land on the frontier. In one sense, this vast opportunity meant the people did not make America, but America made the people. But it was the political ideology of liberalism that unified all Americans, including later immigrants.

Progressivism and the History of Communist Thought

The ideology of progressivism is now predominant in contemporary American left-wing politics. A symptom of our “1776 Moment” is that the Democrats, once stalwart liberals, have become progressives, which means, in fact, they have become socialists. Progressivism’s origins are found in the thought of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Marx and Engels argued that as technology changed so too did the economic means of production. The means of production creates specific economic classes. In each epoch—slavery, feudalism, and capitalism—the classes were perpetually and dialectically opposed to one another.

Under capitalism, the bourgeoisie, or the middle class, owned the means of production and exploited the proletariat, the working class, by extracting surplus value from their labor. For Marx and Engels, the capitalists would always strive to maximize surplus value, which causes accumulation of capital and ever-greater exploitation of the working class, until ultimately the working class overthrows the capitalists. This would then result in the common ownership of the means of production, and thus class would disappear, resulting in communism, the abolition of private property, and the end of alienation. Under communism, the state would no longer be necessary and would wither away.

Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin argued that imperialism allowed the capitalists to extract surplus value from colonial peoples. This transfer of exploitation permitted modest improvements in the conditions of the working class in the developed states like Great Britain, France, Germany, and the United States, forestalling alienation and thus delaying the communist revolution. The responsibility of the international communist movement was to increase revolutionary consciousness among the working class and provoke revolution by seizing control of the state—that is revolution from above via the Communist Party versus a revolution from below driven by the working class as Marx and Engels envisioned. In order for the dictatorship of the proletariat to come to power, there must be a hard core of professional revolutionaries—a revolutionary elite—to advance communism through a centralized, organized, stable, and disciplined cadre, controlled by one man, or at most a small number of men, while providing leadership, instruction, and tutelage for the workers.

These ideas were not limited only to Soviet theorists. In China, the Communist Party applied Lenin’s template, but given its weak urban proletariat, Mao Zedong argued that the rural peasantry could be the vehicle of revolution led by the Chinese Communist Party, which inspired additional communist revolutions in the Third World during the Cold War.

In the West, Italian communist Antonio Gramsci and in Germany the Institute of Social Research, known as the Frankfurt School, argued independently of each other that culture would be the instrument of revolution in the West. Gramsci and the Frankfurt School recognized that conditions for the working class in the West were too good for a Leninist revolution to occur. There would be no revolt by the workers on the factory floor. Revolutionary change would come through shifting bourgeois culture to revolutionary-socialist culture. This revolution could be executed over decades of gradual change.

Gramsci identified ideology as the key both to social change and stable social order. For the proletariat to win required the emergence of a new stratum of intellectuals who would undermine and supplant bourgeois ideology. For Gramsci, the task was to create a new proletarian ideology appropriate for the West which would penetrate the minds of the governed, undermine popular consent to the reigning point of view—the “hegemonic ideology”—and lay the foundation for the new state to be ruled by the proletariat.

Importantly, Gramsci argued that the task was not, as with Lenin in Russia, violent revolution. The actual condition of the West has passed beyond the stage where a communist cadre could seize control of the state in a dramatic revolution. What is required—according to the Gramsci stratagem—is a “war of positions,” in which the moral and intellectual legitimacy of the bourgeois is replaced in the popular mind by the moral and intellectual outlook of the proletariat. This will only be accomplished when the communist intellectuals win over traditional intellectuals to communist goals, not the ideology of communism explicitly, which would be too much to expect. Instead, people would be won over to communism indirectly, through euphemisms of communist ideas and verbiage—progressivism rather than communism.

He argued that the hegemony of the bourgeoisie could be contested by the development of counter-hegemonic narratives. Bourgeois hegemony could be undermined by the media and educational system. Students could be educated by critically aware teachers to resist the hegemonic ideology and their narratives, for example, that capitalism is the best economic system, socialism is inferior to capitalism or “un-American,” merit determines economic, political, and social success, America is not inherently racist, or that the “American Dream” is possible for all Americans. He saw that educational systems may be inherently reproductive for the hegemonic bourgeois ideology. But if they could be captured by Marxists, they would be powerful centers for critiquing the bourgeois ideology, and developing anti-bourgeois counter-narratives, with the expectation that the bourgeois hegemonic ideology would be replaced by Marxism.

The educational system, in particular, was of central importance to shape subsequent generations so that Western countries could become communist states without Leninist revolution. Thus, Gramsci was a realist—there would be no workers’ revolution in the West. The path to communism was different in the West, it would take longer, even possibly generations, and its tools would be largely cultural and ideological, but the end would be the same.

Independently from Gramsci, the Frankfurt School—most significantly Theodor Adorno, Erich Fromm, Max Horkheimer, and Herbert Marcuse—advanced a similar message for advancing communism in the West. Theoretically, the Frankfurt School provided a modern Marxist critique of bourgeois liberal ideology and society and advanced a theory of culture to instigate revolutionary change. This would evolve into critical theory.” Its tools were what they termed the “culture industry”: film, radio and television, literature, theater, print, and which broadened to include psychology, journalism, educational systems including universities, philanthropic foundations, and publishing houses.

In actuality, the “culture industry” should be conceived of as a component of the “ideas industry”—in both cases the aim was to overthrow liberal ideas with progressive ones. The tactics were the same as Gramsci’s: first undermine the existing cultural, political, and social order, and then replace it with communist ideas if not communist verbiage. Formally, critical theory seeks to examine and explain how bourgeois society functions and how it can be changed to realize ideals of equality and social betterment. To accomplish this, the role of critical theory is to critique the existing bourgeois order.

Horkheimer was interested in the failure of the proletariat in the West to fulfill its revolutionary potential assigned to it by Marxist thought; he wanted to discover why they were not behaving as Marxist thought required. The answer was the bourgeois family. The Frankfurt School identified the socialization in the family and its role in generating authoritarian or anti-authoritarian perspectives. Critical theorists concluded that the role of the family in society was essential for the strength of bourgeois society and the inability of the working class to generate sufficient consciousness to effect revolutionary change. In particular, the role of the father and his authority needed to be undermined. This was necessary because of the indispensable education for authority that occurred in the patriarchal family. The family, as the “germ cell” of bourgeois culture, had to be undermined, destroyed, and reconstituted. For critical theorists, as with Gramsci, the bourgeois family—a married father and mother, raising children in a stable community, supported by the church, fraternal organizations, and other aspects of civil society—was a bourgeois institution that perpetuated oppression and was a barrier to progressive change. Accordingly, the family and civil society must be targeted, weakened, and transformed into a progressive force or else their traditional roles must be eliminated.

Thus, the now common portrayal in American art and media of 1950s America in popular culture, including film, television, and literature as embodying these characteristics is a perfect and trenchant illustration of how potent the critique was. It has shaped the image of 1950s America as odious—a political and social order to be rejected—in contrast to the 1960s, which is celebrated as the decade when critical theory began to have an impact on America. Ironically, the conformity required by Frankfurt School and progressivism today is far stronger—more bland, listless, boring, and colorless—than any previous era in America’s history.

Finally, Marcuse is significant for contemporary American politics because of his advancement of the idea of “liberating tolerance,” also called “repressive tolerance.” Marcuse argues that to achieve tolerance of progressive ideas and concepts requires intolerance towards prevailing policies, attitudes, and opinions. Moreover, the extension of tolerance towards prevailing polities, attitudes, and opinions must encompass those which have been repressed. Thus, the concept of “liberating tolerance” means intolerance against movements of the Right, and toleration of movements from the Left.

For Marcuse, the scope of this tolerance and intolerance would be total: including actions, discussions, writings, and speech, the deed as well as the word. Marcuse argues the rise of fascism in the 1920s and 1930s might have been prevented if the Left could have prevented the fascists from communicating. Consequently, the advancement of a progressive agenda requires the withdrawal of tolerance before the deed. That is, at the stage of communication in word, print, and picture. That intolerance is absolute. There is no “marketplace of ideas” for critical theory. Politically progressive expression is permitted, and politically regressive expression is not and may be censored legitimately. Free speech as advocated by proponents of liberalism like J. S. Mill, or giants of American jurisprudence including Louis Brandeis, Learned Hand, and Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., is rejected in favor of controlling expression.

Fundamentally, as Marcuse argued, critical theory does not regard all speech as equal. Speech that is considered oppressive, supporting, or justifying bourgeois ideology, values, and principles is to be curtailed and then eliminated. Speech that is considered progressive: justifying communist ideology, nonwhite racial identities, the variants of feminism that reject bourgeois identity, multiple gender identity, sexual minorities, and immigration is to be advanced. This is because these dogmas promote the liberation sought by critical theory—liberation of those who were once oppressed—and the destruction and replacement of liberalism and traditional American identity, values, and principles. Here are the seeds of “hate speech” laws and speech codes to reverse the “marketplace of ideas” and control thought and expression.

The ideas of Gramsci and the Frankfurt School can be seen as the intellectual foundation of progressivism. There are three major components to progressivism in contemporary U.S. politics.

First, with respect to political power, progressive ideology seeks its concentration in the state. There is a rejection of the separation of powers towards concentration of political control from the executive and the diminishment of the legislative and judicial branches. Equally, federalism is to be erased as the logic of political power advanced by critical theory dictates central control rather than permitting a state, county, or local government to prevent progress. The rule of law as it was traditionally understood is applicable to those who once held power, but as critical legal studies advances, the law must take into account traditional American power structures.

Second, those groups and identities that did not possess political power in the past must be a major factor, if not the determining factor, regarding how the law is applied to their circumstances. Thus, as bourgeois America traditionally oppressed racial and sexual minorities, women, non-Christian religions, minors, and immigrants from non-Western societies, this history of oppression must be acknowledged by the law and incorporated into legal judgments.

Third, progressivism is totalizing in the sense that Marcuse sought, which means that there can be no opposition or allowance of alternative political choices or political thought. The suppression and ultimate elimination of any alternative is a characteristic of all communist governments. All opinions must be in accord with ideological precepts, what the Soviets termed political correctness, and which has become common in American political behavior as well.

Fourth, liberalism’s individualism is replaced with group identification so that individuals are defined primarily by whether they accept progressivism as a political ideology as well as their race, gender, sexual orientation, and immigrant status. The requirement of the ideology is that group identification will define political ideology.

Fifth, progressives replace meritocracy with equity so that principle of outcome supplants that of using talent and skill to gain a position. This is necessary as People of Color have not had and often still lack the privileges of a youth spent in the milieu of education and development that often translate into advantages in testing and entry into elite institutions. The necessary outcome is to place historically marginalized minorities, women, immigrants, and LGBTIQA+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, queer/questioning, and asexual) in positions of power, while white males are delegitimized from those positions.

Sixth, progressivism seeks to replace liberalism and American political culture and history with progressivism’s principles, culture, and history. This is to yield a new history of America viewed through race, gender, LGBT+, and immigrant discrimination. By anchoring the historical past on modes of discrimination, progressives delegitimize U.S. history and allow the political present and future to be based upon a new standard of legitimacy—progressive ideology—without contradiction or a threat to that legitimacy. At the same time, progressivism may attack any remnant liberal beliefs as the metric of acceptable, correct belief is progressivism.

While the objectives of progressivism are anchored in critical theory, the ideology has flowered throughout American society, but especially in journalism, education, civil society, and as the foundation for critical race theory (CRT), it has become the dominant ideology for American elites.

Political opposition is to be destroyed by preventing alternative political parties or alternative ideologies and thought to be expressed. The private behavior of governmental employees must be monitored as well, as progressivism labors to eliminate the private. Increasingly, families must be politically correct, with expressions of politically incorrect speech cause for reporting to authorities and denunciation. Any independent source of thought, expression, or practice must conform to the dictates of progressive thought or be eliminated. These are the ideological origins of “cancel culture” in American political, economic, and social life.

Thus, in contemporary American politics, we have an ideological struggle between the traditional ideology of liberalism and the new ideology of progressivism. CRT serves as the mechanism to accelerate revolutionary change. For Marx, the means of production were the cause, the working class the instrument of revolution, and the place was the factory floor. Today, progressive ideology is the cause, CRT is increasingly the most effective instrument, and the place is everywhere in the culture from classrooms to boardrooms to Pentagon offices.

The Consequences

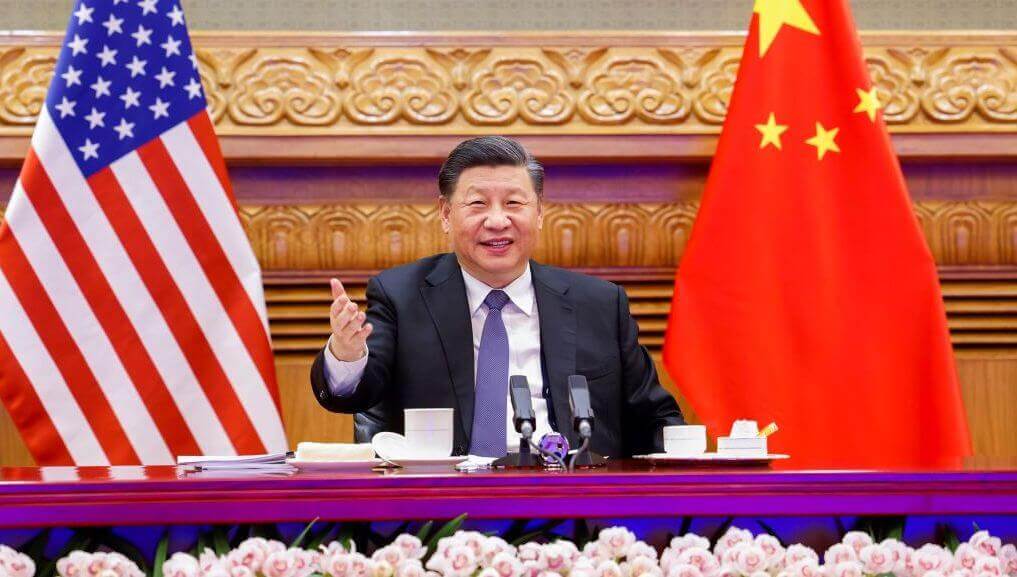

The impact of progressivism is revolutionary: the replacement of liberal ideology and culture with its Marxist alternative. We live at a “1776 Moment” where our governing principles, law, and society are changing into something America has never known. This revolution is altering how America defines itself, its interests, culture, and position in the world. The beneficiaries are America’s enemies, most significantly China, which watches with glee while the United States tears apart the sources of its great strength.

What makes our ideological struggle worse is that American society is caught between liberalism and progressivism. Americans do not know which should be obeyed, or perhaps even which is legitimate. Moreover, there is a generational divide. Older Americans once might have seen progressivism as an infantile disorder but are now awakening to the threat while progressives see older Americans as irredeemably racist.

Lenin asked: Kto, Kogo? (Who, Whom?)” Who rules whom? Today, while the trends favor progressivism, there are still sufficient liberals in numbers and in key positions to challenge progressivism before it achieves complete victory. It is not clear whether liberals will be able to identify progressivism as an un-American ideology that is certain to lead America to tyranny. Or progressivism will triumph, with liberal America consigned to the dustbin of history. On a daily basis, this struggle occurs on both great and trivial issues: which statues should be venerated, and which removed, endless changes to the English language as that great language devolves into Newspeak, or the questioning of the loyalty of members of the military.

As the changes are in a single direction, it is clear who is ruling whom. The consequence of the “1776 Moment” is that the United States will either sustain liberalism as its ideology or become a totalitarian country. The plan of progressivism is clear. To prevent it requires a renaissance of liberalism to assert America’s political ideology, culture, and history.

What Is to Be Done?

As is often the case in a period of ideological upheaval, it is not clear which ideology will triumph. It will be challenging for liberalism to reassert itself as American history and identity for decades have been taught differently to the young in contrast to previous generations, the Baby Boomers (born 1946-1964) or Generation X (1965-1980), who were raised and educated in a United States where liberalism was still the dominant ideology.

To reinvigorate liberalism requires a transition as great as that which has occurred from liberalism to progressivism. It requires capturing the ideas industry that the critical theorists identified and successfully seized. The most important of the ideas industry are K-12 and university education but also journalism and social media, film, streaming services, music, and other elements of popular culture, philanthropic foundations, and publishing houses.

This is singularly difficult to achieve, because progressives control the ideas industry. They also dominate the dissemination of those ideas through media and social media. Liberalism is further disadvantaged because progressivism is supremely intolerant of other ideas. Liberals permitted progressivism to seize the ideas industry because of their support for the “marketplace of ideas.” But progressivism is totalitarian, and so liberals face a supreme challenge. The ideas industry has to be recaptured or alternatives found, as must alternative ways of disseminating ideas.

Similarly, in education, it is not sufficient to require the replacement of CRT as its substitute will still be forged by progressives and inevitably would be nothing more than progressive ideology repackaged. Even to make progress in education would require the federal government, as well as state and local authorities, parents, and PTAs to intervene to halt progressivism’s control over the American educational system from K-12 through universities. Places like Hillsdale College or the new University of Austin are important but cannot stem the tide by themselves. It would take the intervention of state legislatures as some states, including Florida and Texas, have done to have any impact, or for the federal government to link academic tolerance to funding opportunities. Once done, it would have to be sustained. So it is with Hollywood, streaming services, and the other components of the culture industry.

Moreover, there will be countermeasures taken by an ever vigilant and ubiquitous progressivism to prevent an ideological renaissance of liberalism. The example at the University of Oxford of Oriel College’s refusal to remove the statue of British imperialist and philanthropist Cecil Rhodes at the face of the college, despite the demands of the “Rhodes Must Fall” movement, was met with protest from academic staff and over 150 academics refusing to teach Oriel’s students, hurting the educational opportunities for Oriel’s students and its reputation.

Part of the solution for liberals is to study progressivism’s success. What is needed is for liberals to wage a “war of positions” as Gramsci advocated. To assist the liberal response, a Frankfurt School for liberalism is needed to study progressivism. It is incomprehensible that such an institution does not already exist. Liberal donors must come forward to create it. A School of Liberalism would be able analyze the causes of progressivism, how it functions, and what will be its consequences for American society and its place in the world. Moreover, it could answer fundamental questions, including revealing progressivism’s weaknesses, the contradictions in progressivism’s core ideas and tensions within the more moderate wing of the movement and its extreme wing; why progressivism seeks to destroy the society that made it possible; what is the progressive conception of victory over liberalism and timescale to achieve victory; what will it do after victory.

The era of the “End of History” that defined the post-Cold War order is well over. At least in the sense that its author conceived it as the triumph of liberalism, and the defeat of socialism. Hegelian ideological strife has indeed returned. What could not be seen in 1989 was not only the return of ideological conflict but that this conflict would also occur within the United States. Also not foreseen was that liberalism would be dethroned as the dominant ideology of the American elite by socialism in the guise of progressivism. Indeed, it was unimaginable in 1989 that totalitarianism, of either a U.S. or Chinese variant, might define history’s end.

The window to arrest progressivism’s advances is narrowing, and liberals must organize now for the ideological struggle or the progressives will win the “1776 Moment.”