Many words have been written about Angelo Codevilla since he was killed in a car accident on September 20—words about his astute ability to see things that others missed; about his love for his adopted country; about his vast understanding of politics, philosophy, foreign policy; and so much more. And no doubt, many more will appear as time goes on.

Much has also been written about his intellectual energy and courage—he wrote at least a dozen books, along with hundreds of articles and essays—about his teaching at Georgetown, Claremont, and Boston University, about his countless lectures. He always had the courage to state his case and his argument with anybody, be it a United States senator, a secretary of state, or anyone else with whom he disagreed.

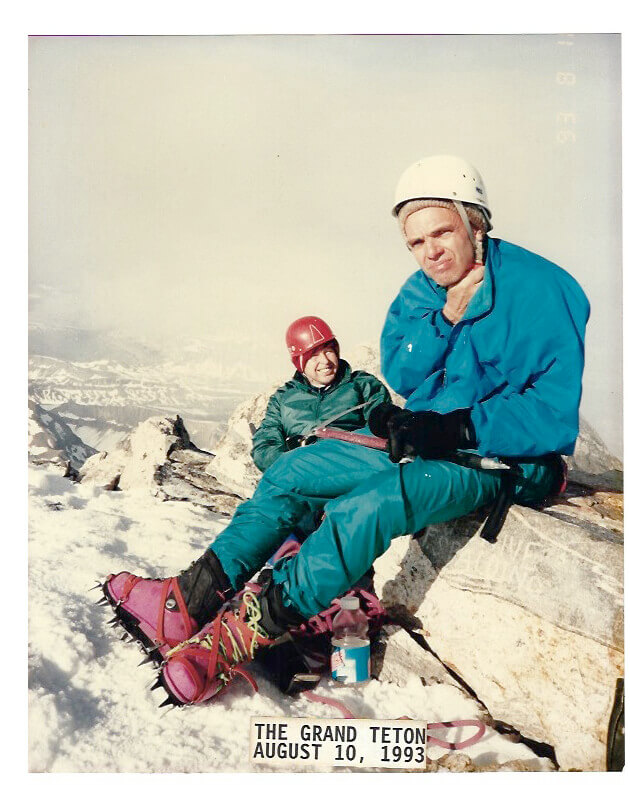

Codevilla also had tremendous physical energy and fearlessness. Let me tell you about one incident that we experienced together.

While visiting him at his redoubt not far from Jackson Hole, Wyoming, he suggested that we climb the Grand Teton together. We could do it, he explained, in one long day up and down. We would need a good trail map, a compass, and some food and water. Wouldn’t it be a great feat to be able to say that we had climbed one of the most famous mountains in America?

I had climbed enough mountains to know that what he had in mind was a singularly bad idea.

A few inquiries led us to Exum Mountain Guides, advertised as “America’s oldest and most experienced mountain guide service.” Situated in a log shack on Jenny Lake near the base of the Grand, it is in the business of guiding mountaineers of various capabilities up the cliffs, and makes clear that inexperienced climbers, without a guide, would be unlikely to return in one piece. Angelo, who had a well-deserved reputation for taking as little advice as possible, was convinced and we signed on to let them guide us to the summit of the Grand. We would first need to participate in a two-day climbing school to learn the finer points of climbing and descending cliffs and crevasses, tying into ropes, rappelling, and general mountaineering safety. We agreed, and by the end of the second day the instructors gave us passing grades.

The next day, armed with freeze-dried food, climbing boots, crampons, ice axes, and hard hats, we started our ascent. After eight miles and an elevation gain of 6,000 feet across green hillsides, through gorges carved out of rock by water and ice, over boulders, and finally a formidable glacier, we came to the Exum hut—10 by 20 feet of canvas stretched over some semi-circular pipes on a stone slab. Not very cozy, but at 12,000 feet above sea level in a chill wind, it was inviting enough. The guides provided us with hot water for our freeze-dried stew and tea and encouraged us to retire early as we would have a long day tomorrow.

We had been warned that the weather prohibited many parties from going further than the hut—seven out of eight in recent days— and that we would not know until morning whether we could proceed. After looking at the glaciers and craggy cliffs above us, Angelo, in an uncharacteristic moment, commented that cancellation might not be that much of a disappointment.

No such luck. We were rousted out of our sleeping bags at 3:00 the next morning and stepped outside into the pitch dark cold and a wind that would have pleased a clipper ship captain. We quickly ducked inside and pulled on all the clothes we had, downed some granola and hot tea, and were about to embark when we were practically blinded by a bolt of lightning followed by sheets of icy rain. It looked like no Grand on this trip. But before long the moon appeared, the wind died down, and our guide Kim pushed us out the door.

Kim was about 45, weather-beaten with piercing blue eyes, and had climbed what seemed like every challenging mountain in the world, including Everest. He was in charge and expected us to do exactly what he told us to do. “We will be at the peak by 9:00 if we hustle and everything goes as planned,” he told us as we started off in the moonlight along a 45-degree spine of rock heading for what he referred to as the “black dike”—a dark wall of rock several hundred yards above us.

As we struggled through air which seemed to be devoid of oxygen I asked Kim what he did in the winter. “Mostly spend it in the hospital getting put back together from the falls I take in the summer,” he said with a grin. “Encouraging,” said Angelo. Kim’s worst accident was while climbing in China with the first group of Westerners allowed in after Richard Nixon’s icebreaking venture. He broke his back in an avalanche that killed three of his climbing partners.

“How do you get out of the mountains in China with a broken back?” I asked.

“On a stretcher.”

“How long did that take,” Angelo asked innocently, “three or four hours?”

“Two weeks,” Kim responded. “The stretcher finally got so uncomfortable that I walked. My back has never felt right since.” He had had 35 orthopedic surgeries, Kim told us, all climbing-related—he was a walking ad for his surgeon. With a fused ankle, a bone missing from his lower leg, and enough scar tissue to scare away a shark, he went streaking up the mountain like a cat.

A little gray was beginning to show in the eastern sky as we reached the black dike, and we stopped to fasten on our crampons—one-and-a-half-inch steel spikes strapped onto hiking boots—and we tied into the rope. Kim led the way connected by 80 feet of rope to Angelo, who was connected with another 80 feet of rope to me. As we inched along a very steep and very slippery glacier, it was clear that the rope was, indeed, our lifeline. Without it, a slip would have resulted in a deathly long slide, ending up only God knows where.

Beyond the glacier loomed a vertical cliff full of spines and crevices and passable only by using intricate hand and foot holds. Everything was coated with ice from the recent rainstorm but not to fear, said Kim, just trust your crampons. The crampons did have a couple of sharp steel spikes sticking out the front of the shoe which were highly effective. Jam your toe into a crack in the rock and it would support your weight as you pulled yourself up. Angelo remarked that they looked like something out of a James Bond movie.

Angelo admitted that he had not been this exhausted in years—a first for him. But there was no rest for the weary. Kim was anxious to get to the top and back down before another storm hit. Each time we stopped to catch our breath, Kim shouted to keep moving, yelling once, “Struggle, Angelo!”

Our confidence built as we climbed, particularly as we realized the crampons and ropes actually worked. We inched our way across ice and rock, sometimes with hair-raising angles, belaying each other with the ropes to avoid fatal slips and falls.

Exum’s literature told us we would experience “sensational exposures,” but no words would prepare us for the “belly crawl”—a horizontal crack in the cliff, about 30 feet long, that would get us from one ledge to the next. Kim seemed a bit surprised that it was lined with sheer ice, but since there was no other route it meant proceeding on toward the summit or turning back. So across we went: toe spikes into a tiny hold below the crack, find a hand hold in the crack and inch sideways supporting weight on toes and elbows. All seemed fine until I looked down—an abyss of immeasurable distance—and decided not to look again. As I pulled myself onto the ledge, I asked Kim about the drop. Three thousand feet, he said. “Holy shit!” Angelo muttered.

As we pulled ourselves over another ledge there was suddenly no more rock or ice above us, just blue sky and, way off in the distance, far below, Jackson Lake, Jenny Lake, and Jackson Hole.

“What a beautiful sight. What a beautiful country,” Angelo said.

But we were not done yet; we still had to descend some 7,000 feet and walk over never-ending ice and rock for 10 miles, all before the sun went down.

Coming down meant finding footholds in the rock and ice by groping with your foot rather than searching with your eyes, a slow and arduous process. One long rappel—sliding down a 160-foot rope well anchored into the rock, took just a couple of minutes to cover what had taken well over an hour to climb. “Are you sure the rope is long enough?” Angelo asked Kim, who assured him that it was. “Well,” said Angelo, “I understand some idiots have died rappelling down 200-foot cliffs with 160-foot ropes.” “Not on my watch,” said Kim. I couldn’t help but remind Angelo that he wanted to do this without a guide. “Shut up,” he said.

Ten hours later we were back at the car, tired, stiff, exhausted, but quite proud of ourselves. In the distance stood Mt. Moran, slightly lower than the Grand, but reportedly more difficult. “Come back next summer, and we’ll do that one, too,” said Angelo. The only difference was that Angelo’s beloved Ann would come also. And we, and Ann, conquered that one, too.

Alfred S. Regnery is president and publisher of Republic Book Publishers.