Sometimes phenomena flare into public consciousness, crowd out other concerns, then disappear. Only later we realize that judicious assessment of the evidence might have saved a great deal of distress.

There are disturbing clues that the Brazilian Zika scare might have been one such phenomenon, fueled by fear, haste, and fallacious conclusions instead of scientific rigor.

The World Health Organization declared the Zika virus a global emergency in 2016 and introduced drastic measures. People panicked not because the mosquito-borne virus causes direct illness—mostly there are no symptoms or just mild malady—but because of the small heads, or microcephaly, that it was believed to inflict on babies born to infected mothers.

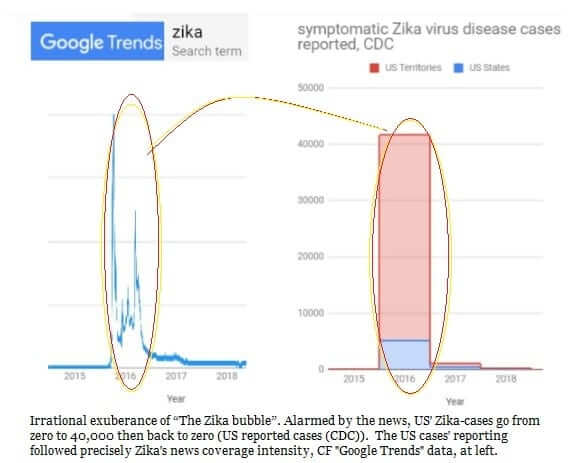

The media went wild, and there were calls to cancel the 2016 Rio Olympics. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control told women who were pregnant or might become pregnant to stay away from nearly 100 countries or regions.

The United States spent more than $1 billion battling the virus’s spread. The 6,000 or so Zika-research articles funded and published after 2014 represent 500-times the previous 50 years’ total.

But let’s zoom out 1,200 miles from Rio to look at the northeast Brazil city of Recife with its endemic poverty, tropical temperatures, and mosquito-friendly open sewage-canals. This was ground-zero for Zika and the babies with underdeveloped brains. It was here physicians perceived more small-head-circumference babies being born amongst the poor.

One of the first microcephaly babies to arouse suspicion of a viral cause was a non-identical twin whose brother was completely normal. Microcephaly is usually an inherited genetic condition or caused by the mother’s alcohol abuse or other toxin-exposure. With her personal clinical assessment that the appearance implied infection, a prominent neuropediatrician inferred a novel cause, despite the brother’s normality under identical circumstances.

She teamed up with a clinician who was investigating other neurological problems associated with an unknown mosquito-borne infection. They joined a WhatsApp group of physicians who communicated rapidly between themselves.

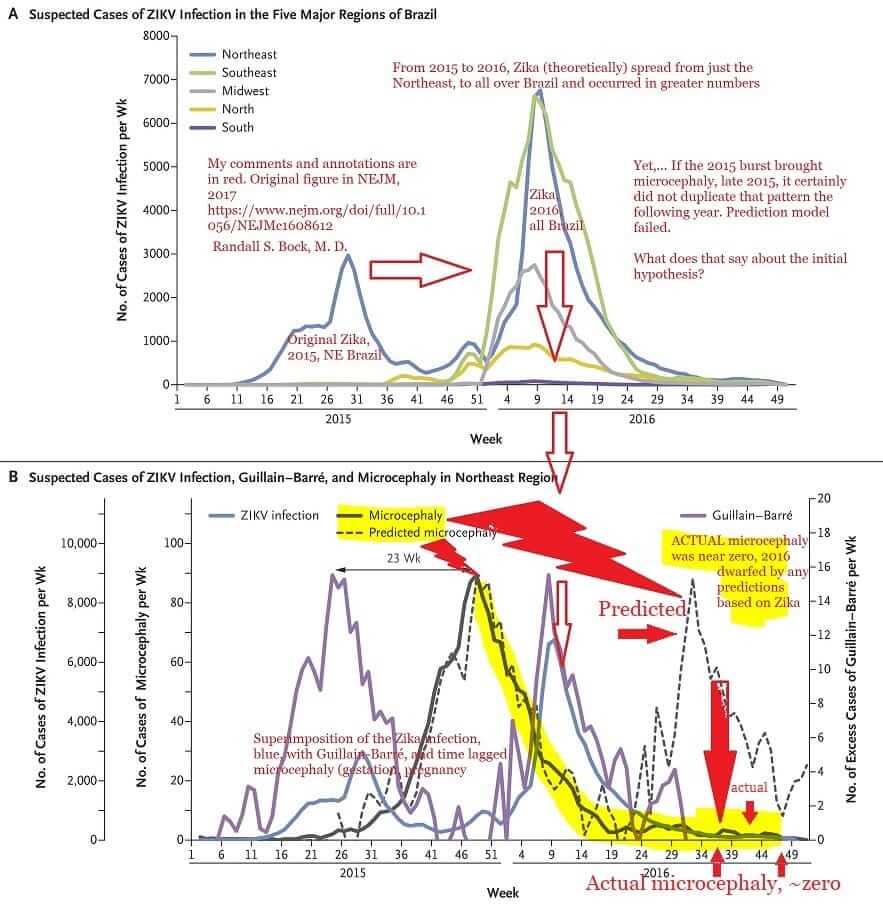

A lack of objective science followed. They issued an alert for small-head-circumference babies and gathered an increase in reports. But was the increase real? Clinicians couldn’t check, because Brazil had not been compiling microcephaly data against which to compare. When scientists eventually looked back at reconstructed data, they found no evidence of a Zika-coincident epidemic.

Second, the Zika diagnoses relied not on lab results but on mothers’ recollections of first-trimester symptoms, such as mild rash or fever. Brazil had no experience of Zika, so it was not equipped for unambiguous diagnosis. In any case, serum tests do a poor job of distinguishing whether the infecting virus was Zika, or its flavivirus-”cousin” dengue. Neither can they reveal how recently the infection occurred. The test that specifically detects Zika does so only briefly after the virus infects a patient.

Third, varying criteria seem to have been used to diagnose microcephaly. Perhaps clinicians used medical standards of normal head sizes that came from richer cities with better-nourished mothers and adults about three inches taller? Babies born into poverty tend to be smaller overall due to a gamut of poverty-related ills. Confusing smaller heads with microcephaly is akin to categorizing every short person as a dwarf. Looking back, it’s clear that in Recife the microcephaly prevalence tracked with income.

Furthermore, there were lower rates in parts of Brazil further away from the WhatsApp-axis.

In 2015, there was a perceived microcephaly increase and there were possible Zika or dengue infections. Any meaningful link between the two was vanishingly rare. An international team of researchers reported that in early 2016 there were 4,180 reported cases of microcephaly in Brazil suspected to be associated with Zika infection, of which only a fifth were investigated and classified. In the end, just six babies were positive for both Zika infection and central nervous system malformations.

Medical knowledge is dispositive: Zika is essentially harmless to humans. In the 60 years prior to 2007, only 14 human infections were documented, all mild, and none causing congenital issues.

More common flaviviruses, such as hepatitis-C and dengue, never cause congenital neurodevelopmental problems. Rubella-virus, which does, damages essentially all infected first-trimester embryos. The highest estimate for Zika puts its hit-rate at 7 percent.

This was likely a case of human instincts’ bowling over scientific rigor. The first instinct is to love babies and care for our young. Nobody wants to be responsible for something that delivers new parents their worst nightmare. Another is the tendency to see patterns whether they are there or not—particularly when you’re looking for them. Two tools that rein in this instinct are the scientific method and the analysis of statistical significance. They were not employed.

The Zika bubble has burst. The failure of the predicted pandemic to materialize is being put down to populations’ developing immunity. But following the initial 2015 Zika outbreak, there was a 2016 spurt of Zika cases in Brazil. In that year, however, according to a letter to the New England Journal of Medicine, there was no reported increase in newborns with microcephaly.

No increase was found during the 2018 outbreak in Rajasthan, India, either.

Disease epidemics are messy, fast and frightening, and they’ll keep coming. To prepare for the future, the least we can do at the end of one is to use the benefit of hindsight to assess how well we conducted ourselves.