The crook is in a parking lot trying to break into a car when he sees a lady with shopping bags approaching her vehicle. Pretending to be a friendly stranger, he insists on helping her load the bags into her trunk. She tells him that since she didn’t ask for his help, he won’t be getting a tip.

He grins and says, “Oh, that’s OK, ma’am. I’ll just take your car.”

That’s a “laugh” line from the 1998 crime film, “Out of Sight.” Presumably, few people in the chuckling audience were ever victims of a carjacking. But the really odd thing is that in the film’s plot, the grinning carjacker is one of the good guys.

Most of the crooks in “Out of Sight” are either mean as snakes or dumb as posts (or both), and in the end, right does prevail, more or less. So the movie is hardly the worst example of glorified crime ever to come out of Hollywood. But it’s long past time for Tinseltown to be getting over its love affair with criminals.

That affair has been going on at least since James Cagney gave his girlfriend a face full of grapefruit in “The Public Enemy” (1931), but it reached a crescendo in the 1960s and ’70s—which, it so happens, is when real-life American crime posted its steepest increases in the modern era.

In those days, a vogue for attractive, successful screen criminals enlisted Hollywood stars including Paul Newman and Robert Redford (partners in crime in “The Sting” and “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid”), Steve McQueen (a gentleman thief in “The Thomas Crown Affair”), Warren Beatty (a charming bank robber in “Bonnie and Clyde,” a charming pimp in “McCabe & Mrs. Miller”), and Rock Hudson (a dashing serial killer—yes, a dashing serial killer—in “Pretty Maids All in a Row”).

It included “blaxploitation” films (“Superfly,” with its drug-pusher hero) and had an international dimension. (In the European caper film “Topkapi,” it’s perfectly all right to be a jewel thief, but unforgivable to be a “schmo.”) The celluloid crime wave subverted even the rock-ribbed rectitude of John Wayne (who organizes a violent gold robbery in “The War Wagon”).

These movies usually ignored the canons of ’30s gangster epics and ’40s film noir, in which the lawbreaking protagonist’s unhappy fate is sealed when he takes his first wrong step. In many of them, the crooks get away scot-free; in others, their violent last stand is depicted as heroic rather than pathetic.

Many of the films went out of their way to portray policemen as ugly, corrupt, or coldly evil. In at least one (“Lawman,” with Burt Lancaster), the peace officer holds center stage as a bloody sociopath. The image common to virtually all of them is that of the happy hoodlum, the gutsy, daring rogue.

Most of the liberal media’s film critics purred happily at this “cute crook” genre. (There were honorable exceptions: New Yorker critic Pauline Kael, for example, tore up “Butch Cassidy” as supercilious and morally deranged.) Tellingly, those same critics were livid in 1974 about “Death Wish,” with its strong depiction of the agonies suffered by crime victims and their survivors. But critical acclaim and commercial success aren’t the only reasons crime on screen was running wild. First, it had to get permission.

No cute-crook picture would have been allowed under the old Motion Picture Production Code, which decreed that “the sympathy of the audience should never be thrown to the side of crime, wrongdoing, evil or sin.” Nor could the gruesome slasher genre have flourished under the code, which required also that “the technique of murder must be presented in a way that will not inspire imitation.” In the 1960s, the code was abandoned. The cinematic crime wave was the result.

A closer look at two hit films, 23 years apart, may serve to illustrate how greatly American culture changed in one generation. I happened to see them one after the other on television one night, and the contrast was striking.

The Late Show was “Shane,” produced and directed in 1953 by George Stevens, a veteran both of Hollywood and of the war in Europe. Set in the late 19th century, “Shane” tells the story of a former gunfighter, weary of violence, who reluctantly defends a group of Wyoming homesteaders against a cattle baron’s efforts to force them off their land. When the cattleman’s bullying and bloodless half measures are thwarted, he sends for a gunfighter of his own, one with no scruples about murder.

This villain (played by a young and very scary Jack Palance) promptly goads one of the farmers into a duel in which the sodbuster is hopelessly outmatched. The gunman dispatches his victim with a sadistic smile, and the farmers are given to understand that the same fate awaits them all if they don’t clear out. In the absence of state law enforcement, it falls to Shane to bring retribution down on both the killer and his employer.

Next on the tube was “The Outlaw Josey Wales,” a 1976 western starring Clint Eastwood. In its opening scene, Civil War guerrillas massacre a Missouri man’s family, turning him from a peaceful farmer into a remorseless killer. The film is little more than an arrangement of set-pieces in which the hero guns down a series of contemptible minor characters.

What struck me then is that Eastwood was playing his part in the very same manner as the gunslinging bad guy in “Shane.” He had the same soft, hissing voice, the same cold air of menace. The only difference was that whereas Palance’s gunman smiled at his victims while shooting them, Eastwood’s character would grimace, shoot, and then spit tobacco juice on the corpse. And this was how the “good guy,” the audience’s role model, behaved!

Equally stark was the contrast in what the two films showed of a gunfight’s aftermath. In “Josey Wales,” it’s just “bang! bang!” and on to the next showdown. But in “Shane,” when the sodbuster dies, we go to his funeral, we listen to the hymns sung and prayers said over his grave, we hear his widow’s sobs. We even watch his dog whining and scratching at his coffin as it’s lowered into the ground.

Moreover, George Stevens’ film shows the humanity of all its characters, inviting the audience’s sympathy for everyone involved. When the hero metes out justice at the end, the mood is not triumph but sorrow. His motivation throughout is never spite; it’s a sense of shared obligation, of duty accepted and fulfilled for the sake of others.

“Shane” is very much an icon of its era, reflecting a generation’s gratitude to all the reluctant warriors, the loved ones who accepted the grim and bloody challenge of defeating the Axis in World War II.

“Josey Wales” is equally a sign of its times. But go back far enough, and you’ll find lots of Hollywood films with nobler themes.

Many, of course, laud duty and honor and have no killings at all: classics like “It’s a Wonderful Life” and lesser-known gems like “The Strawberry Blonde” and “Third Man on the Mountain.” Others show criminal violence while teaching us earnestly to hate it: “The Killers,” “The Asphalt Jungle,” “The Naked City,” “On the Waterfront,” “West Side Story,” “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance,” “Murder, Inc.”

More recent movies are more problematic, mainly because of their harsher depictions of bloodshed; yet many of them retain moral clarity about the human cost of crime: “In Cold Blood,” “Bullitt,” “Hang ’Em High,” “The Onion Field,” “The Black Marble,” “Fort Apache, the Bronx,” “An Eye for an Eye,” “Fargo.”

Francis Ford Coppola’s “Godfather” trilogy might be counted among that bunch, as its tale is tragic and its depiction of mob violence is unflinchingly grim. Yet it seems more a glorification of crime than a repudiation of it. In Coppola’s eyes, the Corleones conduct themselves with dignity, and their victims—from the Hollywood horse’s ass who finds a horse’s head in his bed to the rival mob bosses who fall like tenpins before the Godfather’s righteous wrath—all have it coming to them. Real-life wrongdoers ranging from Mafia don Joseph Bonanno to Iraqi despot Saddam Hussein have fallen in love with this image of the gangster as hero.

The Martin Scorsese gangster films, such as “Goodfellas” and “Casino,” paint a much different picture. They could even be called the anti-Godfathers, full of vicious characters whose disputes are petty and stupid and whose respect for the people around them is tenuous to non-existent. Scorsese’s gangsters are more pathetic than heroic. They are apt to trample the rights and snuff out the life of anyone, fellow hoodlum or hapless innocent, who crosses them in any way at all, and when they finally do meet their end, they themselves are the ones who “have it coming.”

All the same, for every serious and worthwhile crime drama, you have a dozen moral monstrosities: slasher films from “Friday the 13th” to “Scream,” cute-crook movies from “Bonnie and Clyde” to “Natural Born Killers,” mass murder as catharsis in “Carrie” and “The Matrix.”

I stopped paying attention to Hollywood’s output around the turn of the century, but I doubt very much that the past two decades have seen any improvement in that regard. This little mash-up of recent movie mayhem suggests the party is far from over.

Under the old code, Hollywood had a care for what effect its products might have on the more impressionable members of the audience. Not so in the post-code era. And what do you suppose would be the result?

Let’s leave the cinema for a moment and read a line of dialogue from reality: “Murder is not weak and slow-witted, murder is gutsy and daring.”

Those words were written in 1997 by a 16-year-old boy just before he butchered his mother, then shot two of his classmates to death and wounded seven others at a high school in Pearl, Mississippi. His was the first in a series of schoolhouse massacres that, as the riots and assassinations were to the ’60s, have become a signature of our times.

Can a line of responsibility be drawn from the entertainment industry to all that mayhem? Not entirely—though in some cases, where the little morons have consciously aped some atrocity they’ve seen on the big screen, you can just about do that. (“Natural Born Killers” and “The Matrix” were especially fruitful that way.) But there’s enough of a connection to have a lot of us seeking some way to confront those who promote death-worshiping movies, song lyrics and video games.

With regard to motion pictures, however, just how kind and gentle do we want them? Can a diet of “Mary Poppins” appeal to a youth who wants, above all, to be seen as “gutsy and daring”? We often hear about the huge number of on-screen homicides a boy has witnessed by the time he reaches his teens. But children have been raised on tales of blood ever since Achilles slew Hector and David slew Goliath, and indeed long before that.

By way of illustration, here is a bedtime story as told by Barry Lyndon to his son Bryan:

We crept up on their fort, and I jumped over the wall first. My fellows jumped after me. Oh, you should have seen the look on the Frenchmen’s faces when 23 rampaging he-devils, sword and pistol, cut and thrust, pell-mell came tumbling into their fort. In three minutes, we left as many artillerymen’s heads as there were cannonballs. Later that day we were visited by our noble Prince Henry. “Who is the man who has done this?” I stepped forward. “How many heads was it,” says he, “that you cut off?” “Nineteen,” says I, “besides wounding several.” Well, when he heard it, I’ll be blessed if he didn’t burst into tears. “Noble, noble fellow,” he said. “Here is 19 golden guineas for you, one for each head that you cut off.” Now what do you think of that?

“Were you allowed to keep the heads?” asks Bryan. “No, the heads always become the property of the King.” “Will you tell me another story?” “I’ll tell you one tomorrow.” “Will you play cards with me tomorrow?” “Of course I will. Now go to sleep.”

Barry’s tale is given a heart-breaking reprise when young Bryan lies dying.

It may be hard to recall today, but in America the words “shoot-em-up” used to have a happy meaning. It referred to Western B-list pictures starring good-hearted, clean-minded cowboys like Roy Rogers and Gene Autry. Young boys would come home from Saturday matinees, take their toy pistols out to the back yard, and holler “Bang! Bang! You’re dead!” at each other to their heart’s content—and no one had anything to fear. It was all in fun, with no malice at all.

What’s changed? Is it simply a difference in quantity, too much time in front of the boob tube, too many “first-person shooter” video games? Many experts say so. But isn’t it obvious that there has also been a change in quality, in the moral context in which deadly conflict is presented?

A mother who lost her child in one of the early school massacres said something that reinforces the point. With the atrocity at Columbine High School renewing her own grief, Suzanne Wilson of Jonesboro, Arkansas, argued that kids shouldn’t be kept unaware of violence.

“Let the children go to funerals,” she said. “Let them see what happens after the shots are fired. Let’s show them the empty bedroom. Let them know that death is final.”

Wilson was speaking of real life, of course—of real funerals like her daughter Brittheny’s. But her words made me think of the mother’s bereavement in “The Naked City” and of the sodbuster’s funeral in “Shane.”

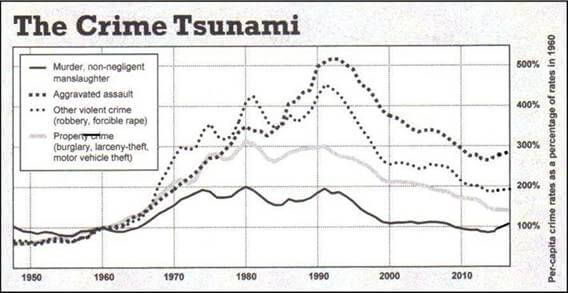

“The Outlaw Josey Wales,” with its serial-killer hero, was released amid a crime wave unequaled in our history, a 50-year disaster that Hollywood’s movie mayhem both reflected and incited. Mercifully, this crime tsunami has receded from its 1991 crest, yielding to tough lock-’em-up policies, proactive “stop and frisk” policing, a resurgent if increasingly proscribed reliance on the death penalty, and stubbornly law-and-order social attitudes.

Yet each of those anti-crime factors has itself accumulated a burden of complaints and countervailing efforts that threaten to move further improvement beyond our reach and may even put whatever improvement we’ve already achieved at risk.

Meanwhile, as shown by the continuing craze for massacres in schools, churches, nightclubs, concert venues and other public places—to say nothing of the relentless daily toll taken by routine murders in our streets, parks and homes—we remain a long way yet from normalcy.

And the happy hoodlum continues to be a Hollywood staple.

Photo Credit: John Springer Collection/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images