To anyone else, January 6, 1993, looked to be an ordinary day. But for Betty Smothers, it was a day she had dreamed of for years. After work and a quick rest, 36-year-old Betty was going house hunting. A mother of six, she was determined to provide a stable home for her children—Warrick (18 years old), Derrick (16), Summer (14), Bricson (11), Travis (10), and Samantha (nine). Betty dreamed of owning a home they could all be proud of, one they could keep in the family for generations. She couldn’t wait to find one for them.

Saving for the down payment had not been easy. Betty had served as a Baton Rouge police officer for 14 years, but her job did not pay well enough to provide for her children in the way she wanted. Her $36,000 salary barely put food on the table for her six kids, so she often worked extra shifts as a security guard. As her oldest grew, she worked even more so he could attend the local Catholic high school. She believed firmly in the power and value of education.

Betty knew there was more to parenting than money. Even as a single mom, she was determined to give her kids her undivided attention every minute she wasn’t working. A track star in high school, Betty volunteered at her local track club so she could coach her children and get to know their friends. Every one of her kids recognized her effort and adored her for it. Betty was a generous and loving mother, and nothing was more important to her than her children.

Twenty-year-old Kevan Brumfield chose a different path. He had worked only three months in an honest job in his life. He could make more money dealing drugs, so why bother?

Sometime in 1987, Brumfield’s and Betty’s lives crossed for the first time. Betty was working security at a grocery store when Brumfield, then a teenager, walked in. He began shoplifting, but Betty caught him. She did not arrest him or turn him in. Instead, Betty gave Brumfield a second chance, making him put back what he had taken and then letting him go. She hoped to teach him a lesson, not derail his life. As Betty’s oldest son, Warrick, said, she was “always giving people second chances to do right.”

But Brumfield did not capitalize on his second chance. Instead, he continued his life of crime, committing one illegal act after another. Shortly after his encounter with Betty, Brumfield was involved in the fatal shooting of a drug dealer. In 1992, he was convicted for attempted possession of cocaine and for trying to steal a gun. Instead of detaining Brumfield until his sentencing, the judge released him.

Neither the conviction nor the pending jail term deterred Brumfield. Even while awaiting sentencing, he returned to crime. On Christmas Day, Brumfield robbed Anthony Miller at gunpoint and stole his gold chain, jacket, and all the cash he was carrying. After Brumfield stripped Miller of his possessions, he put a gun to Miller’s head and pulled the trigger. Fortunately for Miller, the gun misfired. Miller survived, and Brumfield got away.

Just seven days later, Brumfield approached Edna Marie Perry and her young daughter. He put a sawed-off shotgun to Edna’s face and grabbed her purse. Edna pleaded with him to let her keep the pictures of her deceased son that she carried in her bag. Brumfield answered, “Bitch, you dead.” Luckily, he left her alive, making off with only the purse and the memories.

Two weeks, two robberies. And Brumfield wasn’t finished. On January 6, while riding around with a couple of friends looking for a “hustle,” he hatched a plan to steal a grocery store’s nightly deposit. He and one of his companions, Henri Broadway, would hide in the bushes at the night deposit spot; the third friend would act as the getaway driver.

The Brumfeld Crime

While Brumfield was plotting, Betty Smothers was, as usual, working. That day, she reported to the police department for a 10-hour shift. Kimen Lee, the owner of the grocery store, asked Betty to escort her to the bank to make the nightly deposit. So, with her boss’ permission, Betty drove her police cruiser to the grocery store and picked Lee up. She was excited. She was just hours away from touring the houses she dreamed of buying.

Betty never made it to her appointment with the realtor. Shortly after midnight, she and Lee arrived at the bank. As Lee leaned out of the passenger door to make the deposit, Brumfield and Broadway opened fire. Brumfield shot seven times; Broadway shot five. Betty was riddled with bullets, almost all from Brumfield’s gun. Lee was also hit multiple times, but she managed to take control of the police cruiser and drive to a nearby convenience store for help.

Even though he hadn’t managed to grab any cash, Brumfield bragged to a friend that he had just killed “a son of a bitch.” Meanwhile, one of Betty’s fellow officers had to call the Smothers’ house and tell Warrick that his mother had been shot and officers were on the way to the house. Warrick’s mind was spinning—he knew that things were worse than the officer made it sound on the phone. But how much worse?

When the first officer arrived, well after midnight, he asked Warrick, and only Warrick, to accompany him to the hospital. When he arrived at the hospital, he saw his mother lying outstretched and motionless on a bed. Warrick noticed that she was wearing the pearl earrings he had given her. They were stained with her blood. He stared at his mother’s lifeless body and thought that he had just lost his “best friend, soul mate, and guardian angel.”

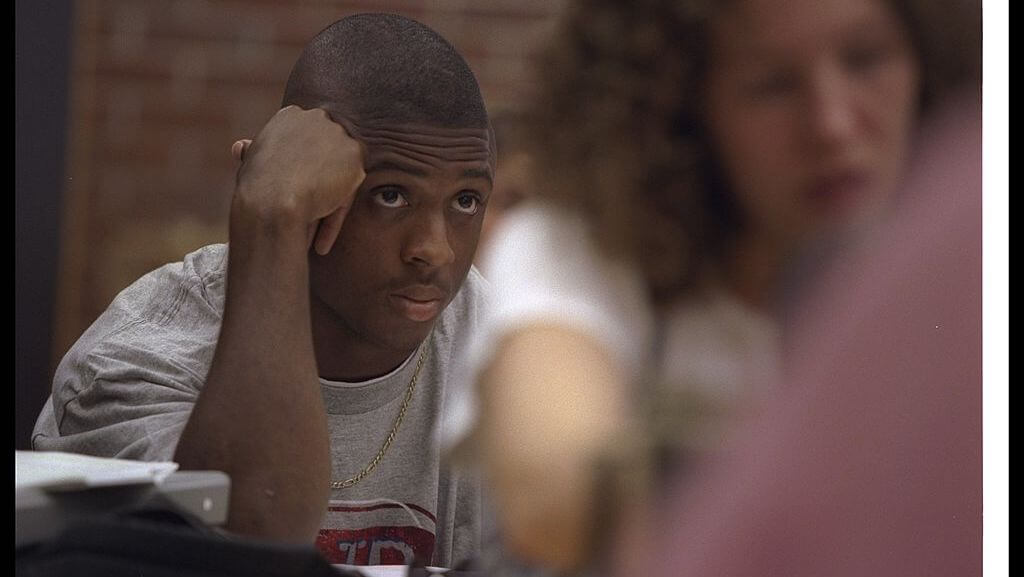

Warrick, a talented running back, had turned 18 just two days earlier. He had been looking at college football programs. In fact, that coming weekend, he had planned to visit the University of Alabama with his mom. Instead, he buried her.

Derrick, Summer, Bricson, Travis, and Samantha had just lost their mother, but Warrick wouldn’t let his brothers and sisters lose more. He thought about the life his mom had given the six of them. She had kept them off the streets. She had kept them dedicated to their studies. And she had paid for Warrick to go to a Catholic high school, where she thought he would receive a better education. Without her, how would they survive?

Warrick Dunn’s Nightmare

In the hospital, during what must have been the darkest, longest night of his life, Warrick sat with his mother’s body and realized that his life as he knew it was over. Brumfield’s crime had thrust Warrick into the role of father to his younger five siblings. Whatever his dreams had been, he had to take care of his brothers and sisters now, too. If it was necessary, Warrick decided, he would forgo college and give up on the NFL. Warrick was his mother’s son. No matter the cost, Warrick would do everything he could to give each of his brothers and sisters their best shot at success.

While Warrick was contemplating life without his mom, Betty’s fellow officers were tracking down her killer. The trail led to Kevan Brumfield. They arrested him, and he confessed at the station, detailing how he’d come up with his “hustle,” waited in the bushes for Lee and Betty, and fired the seven fatal shots with his .38. This time, Brumfield was not released on bail, but that didn’t stop him from attacking another police officer while he was in prison awaiting trial.

While Brumfield spent his time committing assaults in jail, Warrick spent his time piecing together a future for his family. His siblings pushed back on his decision to give up on college and a football career. Warrick’s two sisters and three brothers, as young as they were, had a certain maturity about them. Betty’s five youngest children knew that it was best for Warrick to go to college, and they told him so. A close friend of the family also urged Warrick not to give up on his dreams and stay home, but rather to go to college and become someone who could provide. That way, the friend said, Warrick would set the tone for the entire family.

It was not an easy decision. Warrick was still grieving. Every night that his mom had worked, he had slept in her bed until she got home. The night of her murder, he had an upset stomach. He called his mom, and she told him to come to the Piggly Wiggly convenience store, where she would buy him some medicine that could help settle his stomach. He was tired, so he told her he would wait for her to get home with the medicine. She never did.

As Warrick reflected on all that had happened, he remained convinced that he had to let go of his college dreams and care for his siblings. Without their mother, who else would take care of them?

That’s when Warrick’s grandmother stepped in. She told Warrick that it was his mother’s dream for him to get a college scholarship and graduate with a degree. To make sure Warrick’s siblings were getting along while he was away at college, she could move in with them. So, with his grandmother’s help and her blessing, Warrick finally accepted his scholarship offer from Florida State.

At five foot nine, Warrick Dunn was not your typical Division I running back, let alone at one of the most elite football programs in America. That did not stop him from quickly becoming a superstar. Nothing would.

Despite making stunning plays on the field, Warrick rarely smiled or was happy off of it. He thought about his mom every day, and he kept her bloodstained pearl earrings in a box on his dresser. Those earrings reminded him that she would have wanted him to graduate and care for his siblings. He wanted to make her proud.

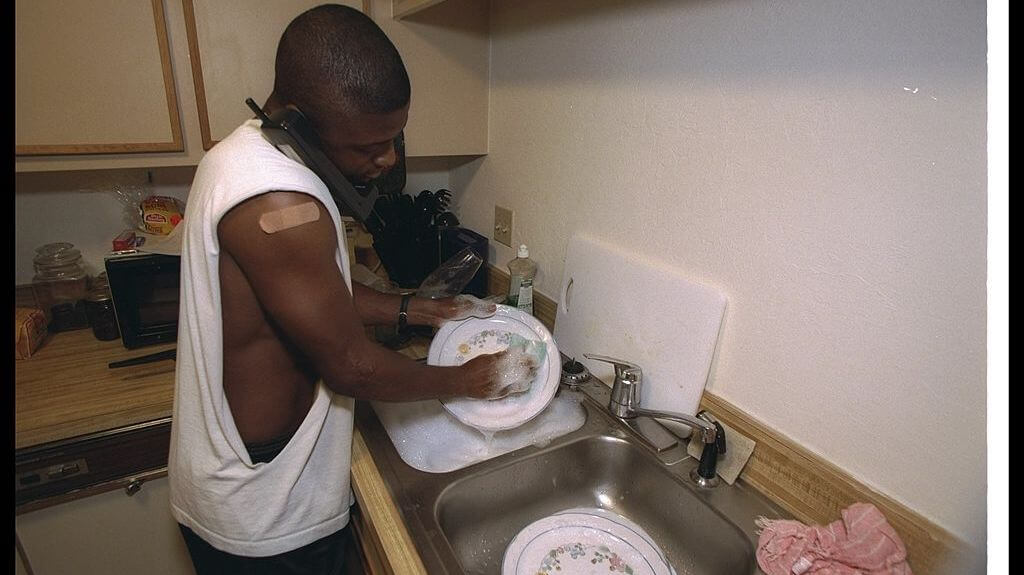

So Warrick rarely went out with his teammates or friends in Tallahassee. Instead, he studied and talked to his siblings. From more than 400 miles away, he was trying to stitch his family’s life back together. Warrick spent most evenings on the phone, checking in on his brothers and sisters. When he had parenting questions, Warrick went to his coaches. His brother Derrick (the second oldest) was taking the lion’s share of the responsibility in raising the others. But as the oldest, Warrick felt he had to make sure everything was all right. He knew the responsibility for his siblings rested with him. Warrick’s ultimate plan was to graduate and provide for his siblings with either his football skills or his education. He was not a typical college student, to say the least.

One more thing made Warrick different from his peers. While most students enjoyed summer vacation, Warrick returned home after his sophomore year for Kevan Brumfield’s trial. A jury of Brumfield’s peers convicted him for the murder that he had confessed to and bragged about. The jury sentenced Brumfield to death. The people of Louisiana had rendered their judgment.

But that was far from the end of the matter. For Betty’s family and their community, closure would be a long time coming. Why? Because while Warrick and Derrick were shouldering the immense responsibility of caring for their siblings, Brumfield was trying to evade his responsibility for the murder of their mother.

A Fair Trial and “A Million Appeals”

For the next two decades, Brumfield fought all aspects of his conviction using every possible legal avenue. First, he appealed his conviction in state court in Louisiana, claiming that the judge’s rulings at trial were wrong, that the judge had improperly instructed the jury, and that his own counsel had made too many mistakes. He also claimed, ironically, that his upbringing by a single mother in a tough environment was responsible for his behavior. The Supreme Court of Louisiana rejected his appeal in 1998. Brumfield then tried to take his case to the United States Supreme Court. But in 1999, the Court denied his petition for review.

A habeas petition is a long shot. The great writ, as it is known, has a storied heritage but a narrow role. Originally, it was only meant to protect people who were being unlawfully detained. The habeas corpus petition was never meant to be a judge-run do-over, a way to circumvent the people’s judgment. Thus, while the petition is often filed, it is granted only in the rarest of circumstances.

Brumfield requested and received “multiple extensions of time” from the state court to amend his habeas petition. His final petition, submitted in 2003, raised many of the claims he had raised before but added a new, very significant, claim, one that had not been available to him at his trial 10 years before: in 2002, in a case called Atkins v. Virginia, the Supreme Court had held that it was unconstitutional—cruel and unusual punishment—for the state to execute mentally retarded individuals. So Brumfield added to his 2003 amended petition the claim that he was mentally retarded and therefore ineligible for the death penalty.

The Louisiana trial court denied Brumfield’s petition, finding that he had not made a sufficient showing of mental retardation, and in 2004 the Louisiana Supreme Court refused to review the trial court’s determination. Brumfield then turned to federal court for yet another bite at the post-conviction apple.

Federal court review is even more difficult than state review. That did not used to be true. In the 1950s, the Supreme Court expanded the habeas writ to cover many things it never had covered before. But as the prison gates opened, Congress became concerned, so eventually it passed a law narrowing habeas review. Congress’ goal was to stop federal courts from second-guessing their state counterparts and to provide victims with closure sooner. Brumfield claimed he was one of those rare people who should be granted federal relief.

This time, Brumfield wanted a hearing in federal court to show that he was mentally retarded. But again, he was in no hurry. After Brumfield filed his petition, his lawyers requested a postponement of the hearing so they could find experts to attest to Brumfield’s retardation. The federal court granted the request.

While Brumfield spent his time challenging every aspect of his conviction, Warrick returned his focus to his family, his classes, and football. Despite everything going on around him, he earned good grades, made it through four years of college, and graduated a star of the football team. Indeed, even though Warrick could have gone to the NFL after three years in college, he stayed four. Why? To fulfill his mother’s dream by making sure he received his college degree.

At the end of his college career, Florida State retired Warrick’s jersey—an honor awarded to very few college athletes. The Tampa Bay Buccaneers selected him as the 12th pick in the NFL draft.

But Warrick’s heart was still broken. Caring for his siblings, attending Brumfield’s trial, attending college, and playing football, he had never really had a chance to grieve his mother’s death. Warrick’s emotions often welled up, though he pushed through them and continued to perform. He was angry and sad. Since Betty’s death, he had tried to be the man she wanted him to be, but he could not enjoy his success or feel happy.

Warrick was not alone. His three youngest siblings were struggling, too. Even with their grandmother watching after them, two were flunking out of school. Warrick decided that they had to come to Tampa Bay and live with him. He took them out of the Baton Rouge public schools and enrolled them in the local Catholic high school in Tampa Bay. He wanted to ensure they stayed on the right path. So Warrick now had two jobs—NFL player and single parent.

Warrick became a star, ultimately becoming only the 22nd running back in NFL history to rush for 10,000 yards. But no matter what he accomplished, he could not find happiness.

Finally, a friend convinced him to see a counselor. He started opening up about that tragic night, its impact on him, and how it had stolen the joy from his life. Working with the counselor, Warrick figured out that he was never going to get past that tragic night until he spoke with his mom’s killer.

In search of closure, Warrick decided to visit Brumfield on death row. Warrick hoped that since Brumfield had confessed, maybe he would answer some of Warrick’s questions. He wanted to understand what could lead a person to inflict so much misery on another. What had Brumfield been thinking about when he pulled the trigger? Had he wondered if he was killing someone’s mom? Someone’s spouse? Someone’s daughter?

But when Warrick finally came face to face with Brumfield, he didn’t find closure or understanding. Brumfield immediately told him, “I didn’t kill your mother. They got the wrong guy.” Maybe Warrick should not have been surprised by such a statement, given that Brumfield had been fighting his conviction for 14 years. But he was stunned all the same. This was a man who had bragged about the killing and admitted to it in a videotaped confession. All these years, and Kevan Brumfield was still denying responsibility.

Yet Warrick was not going to leave empty-handed. He wanted Brumfield to know what he had wrought. So Warrick read a statement he had prepared ahead of time. He told Brumfield what he had taken from Warrick’s family. Tears streamed down Warrick’s face as he recounted the consequences of Brumfield’s actions. He finished by reading a poem from his sister, Summer, titled “The Feeling of a Hurt Soul.”

Warrick got up to leave. Before going, he decided to share with Brumfield one of his favorite quotations from the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.: “The ultimate measure of a man is not where he stands in moments of comfort and conveniences, but where he stands at times of challenge and controversy.” Then he turned and left.

Atkins Hearing for Mental Retardation

Before Warrick could leave the prison, Brumfield’s attorneys asked to meet with him. They asked Warrick to help with their appeals. He couldn’t. While Warrick may have found it within himself to forgive Brumfield, that forgiveness did not extend to allowing the man to escape the sentence handed down by his peers. Warrick promised to pray for Brumfield, but he could not support changing Brumfield’s ultimate sentence after a fair trial and “a million appeals.”

This latest challenge seemed far-fetched to Warrick. The state courts had found Brumfield mentally competent, and that was not something that the federal courts would lightly set aside. After all, federal courts only set aside findings of fact if those findings are clearly unreasonable. And Warrick was certain the state court’s findings were not only reasonable, but correct. It was obvious to him, having been face to face with Brumfield, that Brumfield was mentally competent.

So, without Warrick’s support, Brumfield’s lawyers made a last-ditch effort to get their client off death row. They called him “mentally retarded” and filed an amended petition in federal court on October 1, 2007—more than 14 years after the murder.

A federal magistrate judge was the first one to review the petition. He found that the state trial court’s decision not to grant a hearing on the evidence was reasonable. On habeas review, that is typically the end of the road. But the magistrate judge decided to consider Brumfield’s new evidence and said he was entitled to a hearing. Three years later, in 2010, the district court held what has become known as an “Atkins hearing” to determine whether Brumfield was in fact mentally retarded. Brumfield presented two experts who claimed he was mentally disabled. The State of Louisiana presented three experts saying he was not. Two years later, the district court sided with Brumfield and found him “mentally retarded.” Brumfield had finally gotten the relief he sought.

The State of Louisiana, however, was unhappy with the result, and it appealed the decision to the United States Court of Appeals for Fifth Circuit, which unanimously reversed the district court’s ruling. The appellate court held that the district court had erred in concluding that the state court should have held an Atkins hearing. Indeed, there was evidence in the record that Brumfield could perform his daily life activities and maintain relationships. If anything, Brumfield was a sociopath and had attention deficit disorder, but he was not “mentally retarded” in the sense Atkins meant. According to the state court, he had not pointed to sufficient evidence in the record to justify holding a hearing about whether he was “mentally retarded.” Since this determination by the state court was reasonable, the appellate court held, a federal court was not allowed to second-guess it. Thus, the court reversed the district court and reinstated the death penalty.

Brumfield sought Supreme Court review again. This time, the Court agreed to take his case. It was argued on March 30, 2015, 22 years after Brumfield had shot and killed Betty. Because the Court had announced the right to habeas corpus for death-row inmates with intellectual disabilities in Atkins, it wasn’t obvious what standard courts should use in deciding whether to grant a hearing. The Court struggled with this problem at oral argument: Does the standard come from state law or federal law? If state law, what was Louisiana’s standard? How would Brumfield prove his disability? Could Brumfield introduce evidence not in the record of the original case to show that he was intellectually disabled, since an Atkins claim is a new kind of claim?

The Supreme Court handed down the opinion on June 18, 2015. Justice Sotomayor wrote for the five-justice majority and found that the state court made an unreasonable determination of the facts regarding Brumfield’s mental capacity, that the federal district court was correct to hold an Atkins hearing, and that the facts adduced at that hearing proved that Brumfield was intellectually disabled. For these reasons, he could not be executed. The majority dedicated just one sentence of its opinion to the crime Brumfield had committed, and not a word to the consequences of that crime.

Justice Thomas dissented. He was joined by Chief Justice Roberts, Justice Alito, and Justice Scalia. Justice Thomas pointed out that the case was a “study in contrasts”: “On the one hand, we have Kevan Brumfield, a man who murdered Louisiana police officer Betty Smothers and who has spent the last 20 years claiming that his actions were the product of circumstances beyond his control. On the other hand, we have Warrick Dunn, the eldest son of Corporal Smothers, who responded to circumstances beyond his control by caring for his family, building a professional football career, and turning his success on the field into charitable work off the field.”

Thomas’ Jurisprudence on Brumfield

The majority may not have discussed the crime and the victims, but Justice Thomas did. For him, this case was not just about Brumfield. It was about Betty Smothers, her children, and the people of Baton Rouge. Movingly, empathetically, he described the crime in detail. In an unusual move for a judicial opinion, Justice Thomas spent a section describing how the Smothers family had picked up the pieces and moved on. He started by pointing out that “Brumfield’s argument that his actions were the product of his disadvantaged background is striking in light of the conduct of Corporal Smothers’s children following her murder.” He then described the effect of the crime on the family and how the various members had sought to cope. Justice Thomas also recounted Warrick’s remarkable charitable work—his Homes for the Holidays program, which has become famous. Justice Thomas described how Homes for the Holidays decorates and completely furnishes homes obtained by single mothers, and how Warrick created many other charities, including ones dedicated to service members and victims of Hurricane Katrina, and a grief program for victims of crime. He commended how, while Brumfield relentlessly complained about his circumstances, Warrick took control of his.

Justice Thomas’ discussion of the crime and its effects on the victim’s family was unorthodox for a Supreme Court opinion—so much so that the other three dissenting justices did not join this section of the opinion. Indeed, Justice Alito wrote separately to emphasize that, while the Smothers children were “inspiring,” this section was not essential to the legal analysis in the case.

Of course, the facts were only part of the story. Justice Thomas’ dissenting opinion also explained why he believed the majority’s legal analysis was misguided. The other three dissenting justices joined this part of the opinion, in which Justice Thomas explained that the statutory standard for setting aside factual findings of the state court is high, and Brumfield had not met it. There was more than enough evidence in the record, Justice Thomas noted, to show that Brumfield was not intellectually disabled.

One doctor testified that Brumfield had an IQ over 75 (borderline, not indicative one way or the other) and had not demonstrated any impairment in adaptive skills. The doctor added that Brumfield simply appeared to have “no conscience” and an antisocial personality disorder. But neither of those things make him intellectually disabled. Another doctor scored Brumfield’s IQ even higher.

Ultimately, Justice Thomas argued that Brumfield had failed to rebut the state court’s factual findings or show they were anything other than “eminently reasonable.” To reach the opposite conclusion, Justice Thomas said, the majority had to use sleight of hand: the majority “[took] a meritless state-law claim, recast it as two factual determinations, and then award[ed] relief despite ample evidence in the record to support each of the state court’s actual factual determinations.”

Justice Thomas concluded with strong words addressed to the majority:

What is perhaps more disheartening than the majority’s disregard for both [the habeas statute] and our precedents is its disregard for the human cost of its decision. It spares not a thought for the 20 years of judicial proceedings that its decision so casually extends. It spares no more than a sentence to describe the crime for which a Louisiana jury sentenced Brumfield to death. It barely spares the two words necessary to identify Brumfield’s victim, Betty Smothers, by name. She and her family—not to mention our legal system—deserve better.

Then, in an unprecedented move, he included a picture of Betty Smothers in an appendix.

Warrick and his family were not happy with the Supreme Court’s decision. (But they believe it is appropriate to include the faces of victims, including their mother, in the record.) The majority’s decision meant the saga would continue. Once again, more than two decades after the murder, Brumfield was back in court for a hearing to determine his final sentence.

Warrick prepared to speak once again at Brumfield’s new sentencing hearing. At the hearing, Warrick told the court that he had met with Brumfield and that he did not believe Brumfield was mentally disabled. He also told the court that the judicial system had failed his mother and her entire family by concluding that Brumfield was disabled. “The system is . . . horrible. I do not believe in the justice system because this is not justice,” Warrick said. The state court finally sentenced Brumfield to life in prison.

After the hearing, Kimen Lee, the grocer who had survived the attack despite being shot four times, noted that she continues to live with the incident every day. And Warrick’s family members still struggle to understand why Brumfield would do such a thing, despite coming from a challenging background.

The prosecutor who handled the case said, “We do have intellectually disabled people in our country. This man is not one of them. This is the gravest injustice I have ever seen.” Warrick and his family hoped that this final sentencing would be the end of Brumfield’s intrusion into their lives. Regardless of what Brumfield does next, he no longer has power over Warrick’s emotions. Warrick took that power back in 2007, when he offered Brumfield the gift he had never asked for—forgiveness.