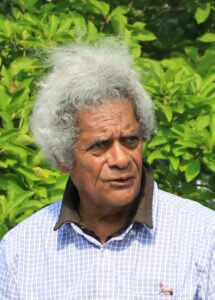

Edward C. Smith passed away peacefully on March 11. He was 80. Smith was the first tenured black professor at American University, where he taught history for 45 years and founded the school’s Civil War Institute. For decades, Smith lectured on art history and led tours for the Smithsonian Institution, the National Geographic Society, the National Park Service, and the Historical Society of Washington, D.C. He was also active in politics but not in the typical partisan fashion. He served in both the Johnson and Carter administrations and also wrote speeches for several Republicans, including U.S. Senator James Buckley (R-N.Y.).

But these impressive achievements (all the more astounding for a man without a college degree) are not Smith’s principal legacy. Many of his students—myself included—can attest that his great gift was a passionate reverence for American history in all of its complexity, along with a love of country and his native Washington, D.C. That reverence was rooted in a deep appreciation of his discipline as a window into the human condition and an essential font of wisdom.

For Ed, a cardinal sin of our era was the politicization of history, or “the reading into the past the prejudices of the present,” as he put it so eloquently. He agreed with the great Catholic writer and historian Hilaire Belloc, who believed that the role of the historian is to bring the past alive through a vivid rendering of events, as well as a close appreciation of and sympathy with the cultural, intellectual, and moral context of the time being studied.

The relentless impulse to instrumentalize history for ideological purposes, which became practically universal in academic circles over the last few decades, was a trend Ed regarded with increasing alarm. He fought against it to the end. Today, those within academia fighting against the politicization of history are few and far between, which makes Ed’s passing all the more poignant.

Ed well understood that our country has had a difficult history with regard to racial animosity. But he also appreciated the fact that this history is unique among Western nations because of peculiar historical circumstances. Our noble experiment of reflecting the equality of all men under the law has been arduous and has experienced serious setbacks at times. The problem of reintegrating millions of formerly enslaved Americans into society has been too long in its settlement, but it was an enormous challenge that was not easy to resolve. After a long struggle, and at great cost for many who fought valiantly and bravely for many years, we largely achieved equality under the law over 50 years ago. The best of the American saga has been one of progressively expanding inclusion in our institutions, making full citizenship and opportunity available to more people of different backgrounds than any other nation has ever successfully assimilated.

Ed Smith cherished that achievement and believed it was being ignored in the rush to depict our nation’s history as one of unremitting and shameful mendacity.

The American story that generations of Americans (including African Americans) learned to cherish and revere is now told as a tale of unmitigated oppression, injustice, and evil. It has taken half a century for this nihilistic, ahistorical view of our past to take root completely. But now that the “long march” through our institutions is virtually complete, there are very few left to challenge the false narrative and speak the more complex truth. Ed was a vigorous champion of teaching the complex truth, inconvenient as it might be for contemporary political narratives.

One example illustrates Ed’s insistence on standing up to the relentless movement to politicize history and use the past as a cudgel in present-day political debates. In the midst of the 1999 controversy in Richmond surrounding a proposal to include a prominent portrait of General Robert E. Lee in a new city park, Ed published an op-ed in the Washington Post titled “In Defense of Robert E. Lee.” The piece has been purged from the Post archives. Evidently, it does not conveniently fit into the current preferred political narrative.

In the piece, Ed described himself as a “third-generation African American Washingtonian who is a graduate of the D.C. public schools and who happens also to be a great admirer of Robert E. Lee.” He bemoaned the fact that Lee is now “under attack by people—black and white—who have incorrectly characterized him as a traitorous, slaveholding racist.”

In fact, Ed pointed out, “Lee never owned a single slave, because he felt that slavery was morally reprehensible. He even opposed secession.” His decision to decline Lincoln’s offer to command the Union forces against his state of Virginia, Ed explained, could only be understood in a historical context. “In pre-Civil War America,” he wrote, “most citizens’ first loyalty went to their state and the local community in which they lived. Referring to the United States of America in the singular is a purely post-Civil War phenomenon.” He notes that none other than Martin Luther King Jr., who “read deeply into Civil War history . . . came to admire and respect Lee.” Concluding his defense, Ed noted that Lee “made a most poignant remark a few months before his death. ‘Before and during the War Between the States, I was a Virginian,’ he said. ‘After the war, I became an American.’”

Ed saw no contradiction between his appreciation of Lee (a rather mainstream understanding of the general that prevailed for a century after the war) with the fact that he was a great admirer of both Lincoln and Frederick Douglass. Indeed, Ed was perhaps the foremost scholar of the relationship between Lincoln and Douglass, which he asserted was the most profoundly influential friendship of Lincoln’s life, affecting both the course and purpose of the Civil War and Lincoln’s own approach to the integration of the newly freed slaves into post-War American society.

For the affluent, mostly white, students attending Ed’s Civil War lectures and tours of the nation’s capital, the effect of his approach to learning from America’s past without presuming to judge the key players of history from an unwarranted perch of contemporary moral superiority could be a bracing—even life-altering—experience. One of those students, Kendra Carey (who later became Ed’s assistant and practically a member of his family after her father’s death), delivered one of the eulogies at Ed’s funeral last month at St. Matthew’s Cathedral in his beloved D.C. She recalled the dynamic walking tours of his hometown:

He transformed the city of Washington. D.C., into his personal outdoor classroom. It was alive to Professor Smith, and his love for it made it a living, breathing entity. It was his Academy, his classroom, and his stage. He filled us with memories of the forts, cemeteries, and statuary commemorating the hard-won battles that led to freedom for all men and women in this country. It was his Rome, and he knew it well.

For me, Ed’s passing offers an occasion to reflect on the triumph of a poisonous ideology built on racial division that has fed into the indiscriminate rage of so many angry young ideologues lashing out against their country. It’s an ideology diametrically opposed to the patriotic appreciation of America’s complex history that Ed passed down to his students.

It’s also an occasion to reflect on another complication that has kept African Americans alienated and marginalized since the legal triumph of civil rights more than half a century ago—namely, the decision of our political and corporate elites to sacrifice the middle class through the importation of cheap foreign labor while exporting the very American industries that made middle-class life possible.

While many groups have suffered as a result of this economic marginalization, black Americans have suffered the most. Already burdened with a historically weak family structure (largely the result of slavery’s cruel family separations), solid and relatively lucrative job opportunities for African Americans with high school educations that had formed the basis for family stability and economic advancement (even during segregation) began to disappear. Coupled with the loosening of traditional moral standards and the erosion of mediating institutions like family, church, and community, this was a recipe for disaster in black communities across America.

While many in our political class encouraged this atomization to increase dependence on government and solidify their own political power, the effect of this economic dislocation on the black family was devastating. When Daniel Patrick Moynihan wrote his famous paper on the crisis in the Black family at the time of the great victories for African American civil rights in 1965, he argued that further economic progress for Blacks would be impeded, even with the removal of legal barriers to progress, unless there was a recognition of the crisis of illegitimacy and family instability in the black community, and a shoring up of African American family strength. The black illegitimacy rate at that time was around 25 percent. Today, it is more than 70 percent nationwide and greater than 95 percent in some inner-city neighborhoods (meaning that the example of family stability and fatherhood is virtually unknown in many places).

In a 1989 letter to the Washington Post that the editors apparently forgot to consign to the memory hole, Ed pointed out the unmentionable:

Black-on-black crime, especially among the poorly educated and people of low-income, has been a problem most well-educated and upper-income blacks in public policy leadership positions have avoided examining—essentially because it is an embarrassment. But the homicide and imprisonment rate among young black males today is so staggering that is cant be ignored any longer . . . Perhaps this crisis in black America would be more understandable if today’s young black men lived in times similar to those of Frederick Douglass and Martin Luther King Jr., in which rabid racism, discrimination, limited employment and educational opportunities were the order of the day. Such is not the case.

That was 34 years ago, and despite the fact that the crisis Ed describes has steadily worsened, the resistance to examining the root causes has only grown. The white illegitimacy rate nationwide now exceeds what Moynihan considered to be a crisis in the black community 50 years ago, and the illegitimacy rate among babies born to white women under 40 today is around 50 percent.

While Ed demolished the whole idea that all inequality of outcome was attributable to “systemic racism,” there is one sense in which the system has completely betrayed black Americans. The destruction of the family and middle-class economic opportunity has hit everyone now, but it has been most devastating for black Americans.

So if we want to talk about “systemic racism,” a large portion of the blame may be laid at the feet of our corporate and academic elites, who replaced economic opportunity with economic exploitation for the sake of their own economic enrichment. That’s a sin that cries to Heaven for vengeance, and it will take a long time to remedy, if it can be remedied at all.

Let’s hope that it’s not too late to restore a patriotic love of our republic’s history among our young that can heal the racial divisions that our sociopathic overlords are encouraging to distract us from their own economic crimes of exploitation and unconstitutional seizures of power. That will start with a steadfast resolve to follow Ed Smith’s example of refusing to abide the politicization of America’s complicated but remarkable history.