For President Reagan, this was it: the “most significant move” of his presidency, as an aide told the Wall Street Journal. On this, the morning of the big announcement, Tuesday, June 17, 1986, the White House press corps, so far as the president could tell, knew nothing; his secret had held.

Three weeks had passed since Chief Justice Warren Burger—stately, white-haired, and baritone-voiced, the very picture of a Supreme Court chief justice, a veteran of presidential intrigues since the Eisenhower era—had abruptly requested a meeting with the president. Aides smuggled the chief into the White House complex that very day. Having served on the Supreme Court since 1969, Burger explained, he wished to retire at the end of its current term and devote himself fully to his chairmanship of a commission celebrating the bicentennial of the Constitution.

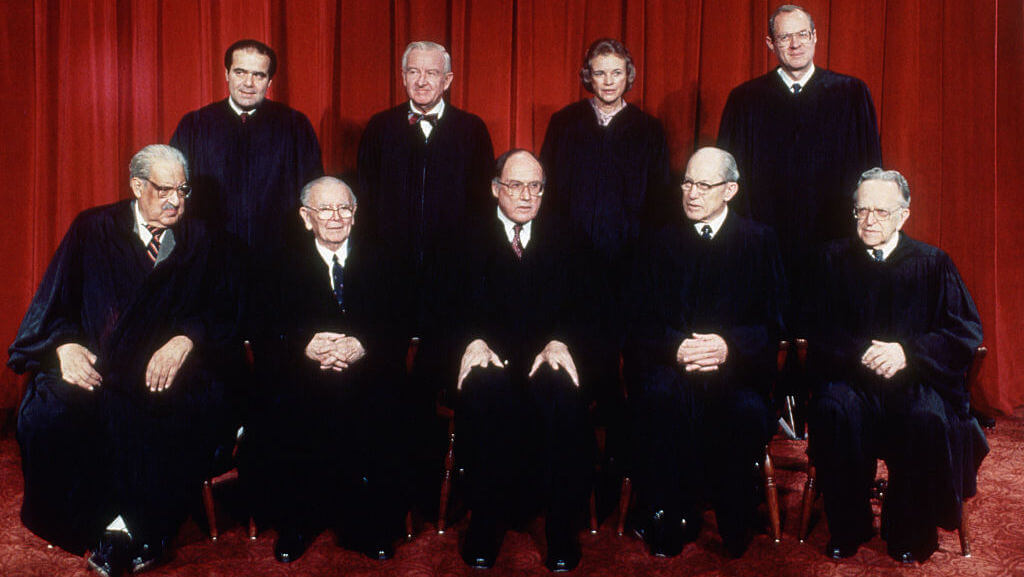

For years, Attorney General Ed Meese and his staff at “Main Justice” had scouted suitable candidates for a Court vacancy such as this one. Ultimately, President Reagan chose to elevate Associate Justice William Rehnquist, a Nixon appointee, to chief justice; and selected for Rehnquist’s seat a brilliant young judge on the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, formerly a law professor and top Justice Department official, named Antonin Scalia.

At the White House and Main Justice, the vast machinery required to submit and confirm Reagan’s two nominees cranked into gear. The press announcement was set for 2:00 p.m. in the White House press briefing room. Two hours beforehand, White House Chief of Staff Don Regan, steely former titan of Wall Street, summoned senior staff, including communications director Pat Buchanan and acting press secretary Larry Speakes, to break the imminent news to them.

Buchanan, the conservative stalwart who had urged Reagan a year earlier to select Scalia, shouted “Yes!” and pumped his fist. All were sworn to secrecy. Speakes issued a press release announcing a 2:00 p.m. event, after which “all the phones in the White House lit up,” a staffer recalled, as reporters tried to learn the topic of the president’s remarks. Scalia arrived, unnoticed, in a “battered” compact car while Burger, forswearing discretion, pulled up in his official black limousine emblazoned with the Court seal in gold.

At 1:57 p.m., Scalia was ushered into the Oval Office. For the judge, a self-described Italian boy from Queens, a deeply devout Catholic and father of nine, the moment could only have been surreal. Just the day before, he, too, had been ushered into the Oval Office, and, with very little ceremony, was offered the vacancy on the Court by President Reagan. The judge had accepted immediately and humbly.

Welcoming him now, ahead of his introduction to the country, were Reagan, Regan, Meese, Burger, Rehnquist, and White House Counsel Peter Wallison. The men chatted amiably for two minutes. Over at the Court, Burger had arranged for his fellow justices to receive copies of the chief’s official retirement letter only ten minutes before the announcement. Stunned, the justices gathered around the TV in the chief’s conference room to take in the news like the rest of the country. Rehnquist’s absence was not unnoticed.

Now the elite group, led by the president, traversed the short, carpeted path from the Oval Office to the briefing room. A door opened, cameras clicked, lights flashed. Reagan, trailed by Burger, Rehnquist, and Scalia, clambered to the presidential podium. Clad in a charcoal grey suit and red tie, Scalia, shorter and darker than the others, the only man onstage unknown to the public, stood alone to Reagan’s right—screen left for Americans tuned in across the country—with Rehnquist and Burger shoulder to shoulder on Reagan’s left. “There was an audible gasp when the three jurists appeared,” Wallison wrote. Pleased the press was caught off guard, Reagan opened with a shake of his head and a triumphant “Heh!”

Minutes earlier, at the Department of Education, the judge’s eldest son, Gene Scalia, then a speechwriter for Secretary Bill Bennett, one of his dad’s poker buddies, marched into the office of the chief of staff, William Kristol.

“We’ve got to turn on the TV.”

“Why?”

“Bill, trust me. This is going to be good.”

The three gathered at a TV. Gene smiled. President Reagan began by disclosing Burger’s secret visit of May 27; the quiet work done to develop recommendations; and his decisions to nominate Rehnquist and, “upon Justice Rehnquist’s confirmation,” Scalia. “In choosing Justice Rehnquist and Judge Scalia, I have not only selected judges who are sensitive to [judicial restraint], but through their distinguished backgrounds and achievements, reflect my desire to appoint the most qualified individuals to serve in our courts . . . Judge Scalia has been a judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit since 1982. His great personal energy, the force of his intellect, and the depth of his understanding of our constitutional jurisprudence uniquely qualify him for elevation to our highest court.”

Reagan closed with praise for Burger, saying the Court under his 17-year tenure as chief had “remained faithful to precedent, while it sought out the principles that underlay the Framers’ words.”

Scalia and the Federalist Society, which the judge had helped found, felt differently about the Burger Court, whose bequeathals to American law had included Roe v. Wade; but Reagan was being gracious. “God bless you,” he said, turning to leave as the reporters shouted questions. Reagan tried to beg off, but the reporters kept clamoring. Already familiar with Rehnquist, they made Scalia their focus.

Chris Wallace/NBC News: Are you satisfied that the judge agrees with you on the abortion issue?

Reagan: I’m not going to answer any questions. If I start answering one, I’ll—

Sam Donaldson/ABC News: Mr. President, what was the process which led you to Judge Scah-lee-ah? Did you know him before? Did people come to you and recommend him? What was the process?

Reagan: I’d previously appointed him into his present judgeship.

Amid the din, the president turned to Wallison. “Can I go now?” “Yes,” the counsel said. “You can go.” Reagan left and Burger took the podium, jovially holding forth on his legacy, future, and health (“never felt better”).

Reporter: Do you approve of the appointment of Judge Scalia?

Burger: Well, the Constitution doesn’t give the chief justice any authority on the subject . . . I’ve known Justice Rehnquist as a colleague for now, what, fifteen years? . . . And I’ve known Judge Scalia since the time he was an assistant attorney general. He’s participated in extrajudicial activities, like being a member of the American team visiting England to study some of their methods. We are not close friends. I have a high regard for each of them, a high regard.

Reporter: [ . . . ] You know Judge Scalia better than anybody else in this room. Give us a little sense, if you would—

Burger: No, I wouldn’t say I know Judge Scalia better than anyone else in this room.

Reporter: Better than anyone else on this side of the room. [laughter]

Burger: Then some of you haven’t been on the job, doing your homework.

The shouting!

“Can we talk to Judge Scalia?” “Can we ask Judge Scalia about his background?” The hounds were on the scent of the new guy, eager to pin him down on Roe. But the hounds would have to wait; Rehnquist was next up to the microphone. The justice said he was “deeply gratified” by the president’s confidence and would do his best to “deserve” it. Queried on his health, Rehnquist parried cannily: all questions that might bear on his confirmation he would defer until his Senate hearing.

Now it was Scalia’s turn to meet the press. With his teenaged debate-show appearances in the 1950s, and his extensive work with the American Enterprise Institute, PBS, and other TV producers, Scalia had undoubtedly logged more time on television than all the sitting justices and their predecessors combined. Yet even for so practiced a performer, the super-charged moment—the White House setting, the live coverage, reporters shouting—was new and, judging by the look on Scalia’s face, a bit unnerving.

Until it was time for him to speak, “Nino,” as Scalia’s family and friends called him, cautiously clasped his hands while Rehnquist, a fixture on the Court for 15 years, casually shoved his hands in his pockets and Burger, ever the sovereign, stood with arms folded. But Scalia was ready for his close-up. His first public comment on the national stage flashed his sense of humor.

Andrea Mitchell/NBC News: Judge Scalia, can you share your thoughts with us as a new nominee—as much as you can say about your philosophy?

Scalia: Yes, on the substance of it, I think I’m with Justice Rehnquist. I—I know a good idea when I hear one. [laughter]

Mitchell: What about your personal thoughts?

Scalia: Oh, my personal thoughts are, for somebody who spent his whole professional life in the law, getting nominated to the Supreme Court is the culmination of, of a dream, of course. And I’m—I’m greatly honored that the president would have such confidence in me and hope that the Senate will do so, as well. And I’ll certainly do whatever I can to live up to it.

The reporters wanted to know if Reagan’s aides had asked Scalia about Roe. The Senate could ask that, Scalia replied, but for now he was going to respond as Rehnquist had. Then they asked if Scalia thought his nomination was going to prove controversial. “I’ve no idea,” he snapped. “I’m not a politician.”

Donaldson: Judge Scall-ya, would you call yourself a tough judge?

Scalia: [pauses] Uh, I—I think that’s—that’s in the category of questions I think—

Mitchell: Can you tell us when you were first approached by the administration?

Scalia: [ . . . ] I think if the president wants that to be known, I’m sure he’ll tell you.

Lesley Stahl/CBS News: [ . . . ] Judge Scall-ya, could you tell us where you went to school and what your background is?

Scalia: Sorry, that’s—

Speakes: We have that in the bins.

Reporter: [ . . . ] Judge Scall-ya, many of the judges appointed by this administration are said to have been subjected to a rigorous screening process conducted under Attorney General Meese. Were you at all—Roe v. Wade aside—asked any of your positions on various points of law?

Scalia: I have—I have no idea what, what the screening process was. And again, you’d have to ask the attorney general.

Wallace: No one spoke to you, sir?

Scalia: Uh—I speak to people all the time.

These early exchanges anticipated Scalia’s interactions with the press for the rest of his life: questions that, in his eyes, ranged from ill-conceived to moronic, answers that alternated between bemused and bothered. An end was called to the Q&A. But the hounds had one final piece of business. They asked how to pronounce “Scalia,” then “Antonin.”

June 17, 1986, Announcement Day, marked the great dividing line in Antonin Scalia’s life: the moment he became a national figure, his rising beamed coast-to-coast, an instant celebrity, symbol, and myth. The public beheld a short, stocky judge with thinning black hair and intense dark eyebrows, the son of an Italian immigrant with a sharp wit and jovial smile, at once cocky and humble, an overnight sensation: sharing the White House stage with Ronald Reagan, Warren Burger, and William Rehnquist, titans all.

How Nino and Maureen, his wife of 26 years, celebrated his nomination, the culmination, the incarnation of the dreams for which they had both sacrificed so much—Scalia’s dream and the American Dream, perfectly entwined—is not recorded. As always with Nino, the schedule afforded little time for emotion. A ton of work lay before them: a fourth FBI background check, the completion of questionnaires and financial disclosure forms, meetings with senators, mock hearings, and, finally, the confirmation hearings themselves, to be held by the Senate Judiciary Committee. There were also ramifications for Maureen and the nine Scalia children, their father suddenly one of America’s most famous men, his family now subject, at varying levels, in ways obvious and subtle, to the perils of fame.

For the next 90 days, Scalia lived in a cocoon, encircled by White House and Justice Department staffers, handlers, clerks, and sherpas: the human capital thrown at Supreme Court nominees to keep them on track to confirmation and away from the news media. The Internet and social media were still years away; but with C-SPAN and CNN carrying the hearings live on cable television, the mid-1980s media landscape bore more in common with today’s than with that of the Watergate era. President Reagan and his team, and the two nominees, understood themselves to be operating in a thoroughly modern arena, governed by global satellite communications, 24-7 news coverage, and hostile advocacy groups. The White House reporters who peppered Scalia were a modern press corps, playing for keeps; and Senate Democrats, while in the minority, were gunning for Rehnquist.

The stakes were high. Newsweek noted that Scalia could serve on the Court “beyond the year 2010.”

Scalia’s Baptismal News Cycle

“Judge with Tenacity and Charm—Antonin Scalia”, declared the New York Times. “Style and Personality Called Contagious: Scalia Described as Persuasive, Affable,” agreed the Los Angeles Times. “Scalia Seen as Major Force on the Supreme Court,” noted the Christian Science Monitor. “Confirmation of Justices predicted by End of Year,” reported the Washington Post.

Here, in Scalia’s baptismal news cycle as public property, emerged the broad outlines of the news coverage he was to receive, as justice and celebrity, symbol and myth, for the rest of his life. Unaware of Scalia’s existence until Tuesday, clueless about the trails he had blazed through academia and on the court of appeals—“His opinion on the Court’s decision is not known,” (the Chicago Tribune, of all outlets, formerly Scalia’s hometown paper, reported falsely about Roe)—the press struggled to catch up.

But reporters are quick studies, and after calls to sources, they captured accurately the high esteem in which the judge was held in legal and political circles, his extraordinary conglomerate of skills and attributes.

“It is his combination of affability and acumen, of energetic fervor and astringent intellect, that makes him potentially one of the most influential of justices,” reported Time. “Very bright, professionally able, personally charming. And a consensus builder. That’s the way legal scholars describe Antonin Scalia,” the Christian Science Monitor related: “Through his considerable powers of persuasion . . . Judge Scalia may wind up altering the balance—and thus the outcome of close decisions.” “Judicial foes and supporters alike describe Antonin Scalia . . . as an aggressive conservative who combines persuasive powers with unusual affability,” the Los Angeles Times said, noting such qualities would make him “stand out in a body where consensus is crucial.”

However, the moment also gave full flight, among the ostensibly objective press, to a careerist narrative of the judge’s rise to this moment. That Scalia could have so consistently and perfectly embodied the philosophy of judicial restraint that Reagan and Meese championed, that as an academic and jurist he had been compiling such a record for many years before the prospect of a Reagan presidency materialized, seemed beyond the imagination of the news media; such powerful synchronicity could not be organic but must, rather, have been the result of Scalia actively auditioning for Reagan, currying favor, flashing his card, earning his stripes.

“In his opinions while on the appeals court,” said the Washington Post, Scalia “appeared to go out of his way to express views consistent with those of the Reagan administration . . . That practice fueled speculation in legal and political circles that he was actively campaigning for a high court nomination.” “A few of Scalia’s colleagues on the Court of Appeals,” reported Time, “suspect that he wrote a number of strongly-worded dissenting and concurring opinions on the conservative side of cases simply to advertise that he was 100 percent in accord with Reagan’s views.”

Colleagues of Scalia’s from every phase of his career, interviewed at length, dismissed such sniping as untrue: Routinely, they said, Scalia had produced legal opinions whose outcomes he personally lamented, because he so fastidiously followed the law above all else, as well as other opinions which he knew would not endear him to higher-ups, lawmakers, and others who could affect his future career prospects.

The cheapest shots came from a fellow outer-borough New Yorker, the self-styled Bard of Queens: Daily News columnist Jimmy Breslin, who took the R Train to scope out Scalia’s boyhood neighborhood in Elmhurst. The people there, Breslin wrote, were “pure Queens . . . Their major asset was their obstinacy.” He depicted the neighborhood—and by extension, Scalia himself—as insular, contemptuous, xenophobic:

Scalia, as Roman Catholic as a retreat, was forced to attend Boy Scout meetings at the Methodist church because the natural place for a Boy Scout troop in Elmhurst, St. Bartholomew’s Roman Catholic Church on Ithaca Street, had an Irish pastor at the time who would not allow a Boy Scout troop in his place because he might wind up with Protestants and, God forbid, a Jew inside his halls.

Xavier High School, from which Scalia had graduated as valedictorian in 1953, was, Breslin sneered, “fully integrated: half Irish and half Italian . . . an atmosphere that causes students to feel superior to begin with. As the school was Jesuit, the atmosphere was also one of being superior to all other Catholics. And then since Xavier was a military school, its students were aggressively superior.”

Emphasize His Rulings, Not His Qualifications

Editorial opinion split along ideological lines. “Although we might not agree with Antonin Scalia on every issue,” said the Wall Street Journal, “he is an excellent choice.”

Even before he joined the [federal bench] he had come to our attention as the editor of Regulation magazine and as one of the crew of bright young scholars teaching at the University of Chicago law school. His specialty is separation of powers . . . Although the Warren Court era led legal scholars to study the Bill of Rights almost exclusively, Judge Scalia is part of a young group of scholars who have concentrated on the Constitution itself . . . Judge Scalia is [also] an expert on how the post-New Deal regulatory system works, and especially on how it fits—and doesn’t fit—into this careful system of checks and balances.

The left-leaning Baltimore Sun, while conceding Scalia’s “impeccable” credentials, took a dimmer view.

We question his marketplace approach to the law—is this or that constitutional right worth the price paid to protect it? We certainly question his view that the press does not deserve the freedom to probe and write about important individuals and institutions. He may not be, as [New York Times columnist William Safire] called him last year, ‘the worst enemy of free speech in America today,’ but he’s no Warren Burger, either.

Reaction on Capitol Hill and among major interest groups also split along ideological lines. “Senate Republicans Praise Choices,” the Los Angeles Times reported. Democratic lawmakers, aghast that Reagan even had an opportunity to appoint another justice, labeled the nominations “very frightening,” with Scalia said to be “even more of a conservative hard-liner” than Rehnquist. Senator Biden, ranking Democrat on the Judiciary committee—who had approved Scalia’s nomination to the D.C. Circuit—was all over the place. On one hand, Biden recognized that Rehnquist and Scalia were “in a different league intellectually” than most nominees; on the other hand, the Delawarean argued that while Scalia was “unquestionably qualified” to sit on the Court of Appeals, it was now “an open question whether he is qualified to sit on the Supreme Court.”

With Rehnquist sure to draw heavy fire, however, and Scalia’s credentials so impressive, the consensus foresaw little opposition to the judge. Democratic appointees on the D.C. Circuit endorsed him. Judge Mikva recalled “a delightful colleague . . . good sense of humor, lots of human qualities, an uproarious laugh.” “I think he does listen, he has an open mind, he enjoys the dialogue,” Judge Patricia Wald told the Washington Post. “I do have the sense he has strong feelings about particular things, but that he does come to each case willing to listen to both sides.”

And Biden’s fellow Democrats on the judiciary committee followed suit. Pat Leahy of Vermont called Rehnquist and Scalia “very competent, highly qualified men.” The New York Times heard “lawmakers from both parties” say Scalia’s “reputation for intellectual brilliance would mute criticism from senators who disagreed with his conservative rulings.” U.S. News & World Report predicted both Rehnquist and Scalia were “likely to sail through Senate confirmation.”

To liberal lawyers and advocacy groups, which always followed closely the rulings of the D.C. Circuit, the spirit of bipartisanship that greeted Scalia on Capitol Hill was deeply disappointing. The activists would not allow the nomination to go unopposed. Alan Dershowitz, then a liberal Harvard law professor, branded Rehnquist and Scalia “two of the finest 19th-century minds in America.” Laurence Tribe, also a liberal Harvard law professor, took the matter more seriously, calling the nominees “distinguished and bright men,” jurists “of tremendous affability,” and warning: “There is no doubt that Scalia will shift the balance of the Court over the long run because he is so much more intelligent and powerful and affable than Warren Burger.”

Social justice warriors, civil rights groups, women’s organizations: All began mobilizing. They started, however, from behind the eight ball. The American Bar Association—which had withheld its highest rating when Scalia was appointed to the appellate bench—now ranked him “well qualified” for the Supreme Court, the supreme blessing, following an “exhaustive investigation,” from the 14 members of ABA’s Standing Committee on the Federal Judiciary. Their unanimous opinion held Scalia “among the best available for appointment to the Supreme Court,” saying he had demonstrated across his career “outstanding competence, the highest integrity, and excellent judicial temperament.”

The ABA inquest was far more comprehensive than the FBI’s that year. The dean and faculty of the University of Michigan law school were enlisted—alongside two other teams, made up, respectively, of practicing lawyers and law students—to review Scalia’s opinions. More than 340 interviewees were questioned, including more than 200 state and federal judges, among them the justices of the Supreme Court and Scalia himself.

Most of those who know him spoke enthusiastically of his keen intellect, his careful and thoughtful analysis of legal problems, his excellent writing ability and his congeniality and sense of humor. Almost all who know him, including those who disagree with him philosophically and politically, expressed admiration for his abilities, and for his integrity and judicial temperament.

The legal fraternity could say whatever it wanted about Scalia; left-wing activists would emphasize his rulings, not his qualifications, to brand him as out-of-the-mainstream.

“Liberals Portray Scalia As Threat but Bar Group Sees Him As Open” the New York Times reported. So the playbook was written: When a conservative Court nominee is well qualified with no record of disputed prior conduct, such as the polling-site activities that dominated both Rehnquist hearings, then the liberal line of attack shall be that the nominee’s views are extreme: racist, sexist, oppressive.

Legal researchers burrowed into Scalia’s articles and rulings. Progressives declared war. “There is room in the courts for conservatives and moderates,” said Ralph Neas, executive director of the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights. “But this man is not within the parameters of acceptability. He has shown a remarkable insensitivity to victims of discrimination.” Eleanor Smeal of the National Organization for Women said the judge’s views were “totally out of keeping with where we are in today’s society.”

But Obviously Only You Heard

For one interest group, the Scalia nomination set off an explosion of pride and joy. Not since Rocco Marchegiano of Brockton, Massachusetts, better known as Rocky Marciano, captured the world heavyweight championship, back in 1952, had the Italian-American community so rejoiced over the public triumph of one of their own. Scalia’s rise meant even more, because his achievement, unlike Marciano’s, was purer, wholly intellectual, academic: untainted by the violence of the ring and the dishonor of organized crime, which had periodically controlled professional boxing.

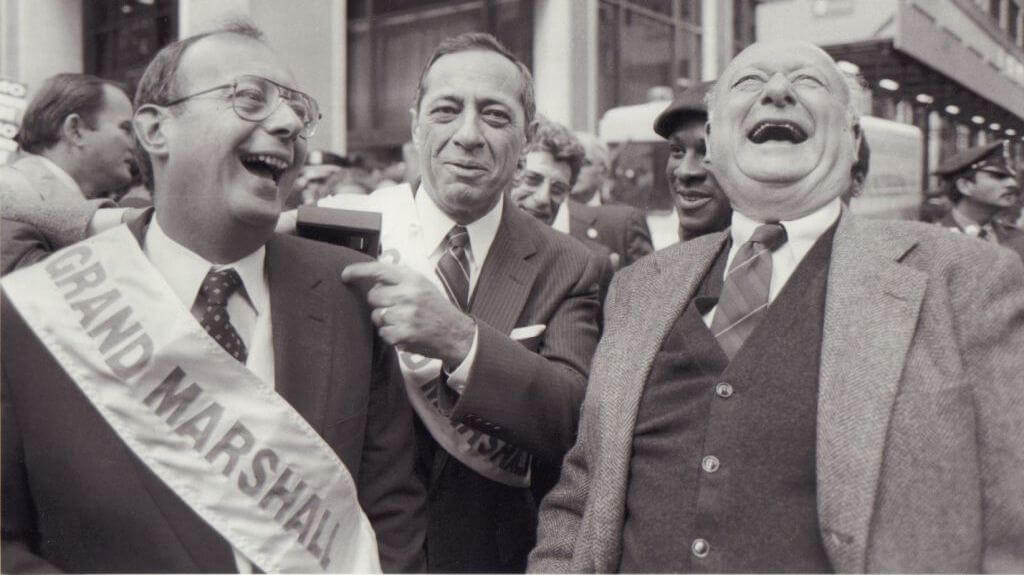

The 1980 Census listed 23 million Americans of Italian descent, roughly 9 percent of the population. Recent years had witnessed several ground-breaking appointments and achievements, including the crusading Watergate roles of Judge Sirica and House Judiciary Committee Chairman Peter Rodino (D-N.J.); the ascension, in 1978, of A. Bartlett Giamatti to the presidency of Yale; Mario Cuomo’s election as governor of New York in 1982; and the selection, two years later, of Geraldine Ferraro as the Democratic nominee for vice president.

The preceding generation had also produced several films, huge box office hits and Oscar winners, with Italian themes—among them “The Godfather” (1972) and “The Godfather: Part II” (1974), “Rocky” (1976), and “Saturday Night Fever” (1977)—that celebrated the community while stirring ambivalence within it.

Scalia trumped all that. When he donned the robes of an associate justice, his honor would be pristine, holy: supreme. “Italian Americans throughout the nation are thrilled and over-joyed,” Charles Porcelli, president of the Joint Civic Committee of Italian Americans, wrote Reagan on June 19. “The long-sought dream of Italian Americans is now at long last a reality and Italian Americans everywhere are eternally grateful to you.”

Judge Scalia is eminently qualified and has the wholehearted support of all Italian Americans as well as the many ethnic groups in the country. His selection has heightened the spirit and morale of our people . . . We are convinced that Judge Scalia will perform with dignity [and] dedication and will be guided in his decisions on the basis of what is in the best interests of all Americans regardless of race, creed, or social status.

By recognizing “the tremendous academic and professional accomplishments of this unique individual,” wrote Dante Sarubbi of Scalia’s native New Jersey, “you have brought honor to all Italian-Americans.” Bruno Giuffrida, head of the Supreme Lodge of the Order Sons of Italy, thanked Reagan for embracing those “who have heretofore been denied access to America’s highest court.”

“Our deepest thanks for your courage and understanding,” cheered the country’s largest Italian-American service organization.

Antonin Scalia will make you proud of your choice and will help make America even greater . . . You should be credited with the foresight you have in America’s finally realizing that intelligence, justice, humaneness, and knowledge of our laws exist in the Italian community just as they exist in other heritages which make up America.

“The Italo-American community for many years has attempted to convince past presidents of these United States that simple justice and equity cried out for an appointment of an American of Italian descent to the Supreme Court,” wrote Frank Montemuro, Jr. “Our pleas were made to Presidents Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon, Ford, and yourself. They all listened but obviously only you heard.”

Cordial Conversations

A June 19 White House staff memo, captioned “Subject for Discussion with Judge Scalia” and previously unpublished, advised the director of the legislative affairs office: “You should impress on him the importance of working with this office.”

Advise him that the nomination papers will be transmitted to the Senate today . . . so as to allow the clock to start ticking in the Judiciary committee . . .

Advise him we will start setting up courtesy calls after the Congress returns from the July 4th recess . . . Senator Thurmond has pledged to speed the process up, so it is probable that confirmation will take place before the August recess . . .

Justice Department, in the guise of [assistant attorney general] John Bolton, will prepare briefing books on the senators, their concerns and special interests in the judicial field.

Scalia’s first meetings on Capitol Hill, scheduled for July 15, were with Senators Howell Heflin, Democrat of Alabama, and Alfonse D’Amato, Republican of New York and a fellow paisan. The next two weeks were a blur, as Scalia and his handlers rode the elevators up and down the Hart and Russell Senate Office Buildings for cordial conversations with two dozen of the chamber’s major and minor figures: Bob Dole, Ted Kennedy, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Leahy, Arlen Specter, Paul Simon, Orrin Hatch, Chuck Grassley, and a freshman from Kentucky named Mitch McConnell.

At Scalia’s side was Fred McClure, the White House lawyer and legislative aide—young, savvy, African-American—who shepherded Scalia through the process. “He was absolutely enthusiastic,” McClure said of the Senate sit-downs. “It was like it was one of those things he had been kind of waiting on all his life . . . the next step to the brass ring.”

The Kid from Queens charmed and dodged with ease. No one made it easier, though, than D’Amato, another Italian American from New York, a year younger than Scalia. “I would have sworn that I was at some type of Italian reunion,” McClure told me, his account previously unreported. “[D’Amato] was just busting at the seams and excited about Scalia . . . . They had a lot in common.”

After the two paisan finished “hugging and shucking and jiving with each other,” McClure recalled, he and Scalia sat down on a couch as D’Amato retrieved a clutch of VHS tapes. “Nino, you’ve got to see this! You’ve got to see my mama, who is in my commercials this year!” Proudly, he made the future Supreme Court justice watch a series of political ads featuring Mrs. D’Amato kvelling over what a good boy her son, the senator, was.

“That was the complete extent of the interview,” McClure said. After that, D’Amato escorted them out of the office and “told the press how much he loved Nino Scalia and what a great justice he was going to be.”