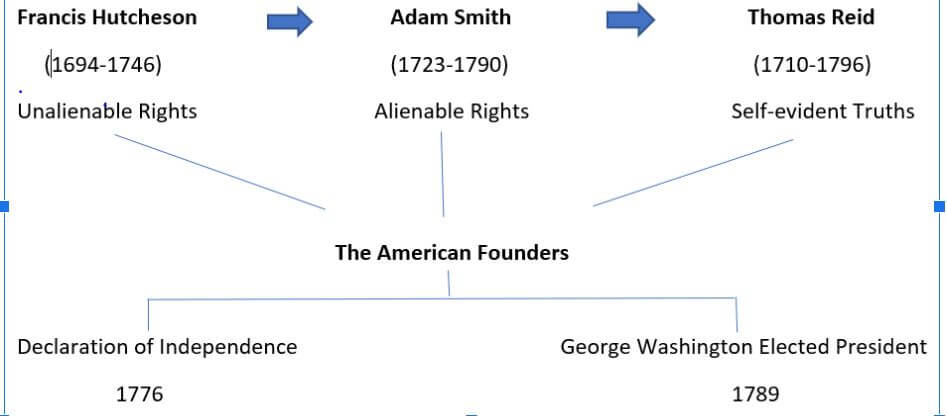

In Common Sense Nation: Unlocking the Forgotten Power of the American Idea, my goal was to tell the story of the Scottish Enlightenment’s impact on the American founding in the fewest words possible. Recently, it occurred to me that an image may have helped the reader follow the story.

Below is that image, a snapshot of the fascinating story of the Scots and the founders.

Across the top are the three great thinkers of the Scottish Enlightenment who shaped the American idea. Their lives and careers in Scotland are remarkably linked. Francis Hutcheson, the founder of the Scottish Enlightenment, taught philosophy at the University of Glasgow in Scotland from 1730 until his death in 1746. He mentored Adam Smith who succeeded him in the same prestigious professorship. Thomas Reid succeeded Smith when Smith stepped down in 1763.

Theirs is a remarkable story of philosophical progress and benefit to humanity.

Smith’s Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776), in the words of James Otteson, “whether judged by its influence or its greatness, must be considered one of the most important works of the millennium.” Hutcheson had prepared the way for Smith by making the case that we have two fundamentally different kinds of rights. Hutcheson: “Our rights are either alienable or unalienable . . . our right to our goods and labours is naturally alienable.” Smith took up the task of examining our alienable rights.

Your right to your car is an alienable right, that is, your ownership of your car can be transferred to the ownership of another person; you can sell your car or give it away. Smith’s profound examination of alienable rights shaped America. Lord Acton saw this for himself when he visited America in 1853. In his published account of his visit, after an introductory paragraph with acknowledgements of those who had been helpful on his visit, the first paragraph of his actual account begins with these comments.

“There is no primogeniture in America. It is strictly forbidden. One may leave his property by will, and everybody makes a will. There can be no entail.”

This difference between Britain and America got first mention. It was that remarkable for Acton.

According to Hutcheson our right to our property is naturally alienable. It follows that primogeniture and entail are unnatural, unnatural restrictions on the natural alienability of property. The founders, especially Jefferson and Madison, had made sure to eliminate these holdovers from British law and custom, and what a difference that made!

Of course, it makes sense that Acton would be struck by this difference. After all, he was Lord Acton within a system of primogeniture and entail; without that system he would simply have been John E.E. Dahlberg-Acton. But the effects of that system were not restricted to the world of barons and hereditary baronets. We can get a vivid experience for ourselves of the difference that system made in the lives of people who were not members of the nobility simply by re-reading Pride and Prejudice or Sense and Sensibility. Literary critics will tell you that these are to be understood as impeccably entertaining comedies. But I suggest you re-read them with an eye to the impact of the entail and primogeniture system on the lives of these young ladies and their families. Doing so may give you a very different idea of what Jane Austen was up to.

In the same year Smith published Wealth, the founders sent forth their Declaration to the world. Smith had developed the economic and social implications of a deep understanding of alienable rights; the founders set about developing the political and social implications of a deep understanding of unalienable rights. John Adams put the founders’ idea like this: “All people were born free and equal, and have certain natural, essential and unalienable rights.” Working out the implications of that understanding of the human person was the great task of the founders. The greatness of their achievement is unrivaled in the field of human action.

The founders declared they were stating self-evident truths. They had gotten their understanding of self-evidence from Thomas Reid. In 1776, in a world headed in a very different direction than the direction the founders took, the German philosopher Immanuel Kant had written it was a scandal that philosophy had not found a rational proof of the existence of the external world. Reid was not scandalized. According to Reid, it is self-evident that the world in which we live exists. No proof is needed; in addition, it is impossible to prove it exists because its existence is a pre-condition, one of many, of the very possibility of proof. To understand the statement “the world exists” is to know it is true; it is self-evident.

With Reid’s help, the founders accomplished great things. It is, the founders declared, self-evident that everyone is born free and equal. Only unnatural systems like the one that elevates a baron above a commoner obscure this truth. In the new world they were making, everyone would be free to rise as high as his talents, dedication, and—yes—good fortune would allow.

Although Hutcheson was the modern philosopher most widely assigned to American college students in the founders’ time, by the time Acton visited Harvard during his one visit to America he found that Reid had risen to first position: “In the third [the junior] year Reid becomes a text-book.” Acton would have found Reid occupying the first position at whatever American college he visited. Reid’s commonsense realism had become, in the words of Arthur Herman, “virtually the official creed of the American Republic.”

The Scottish Enlightenment went into decline in Scotland not long after Reid’s death, but it had found new and vigorous life in the New World. In the words of Allen Guelzo: “Before the Civil War, every major [American] collegiate intellectual was a disciple of Scottish common sense realism.” Because American colleges relied on Reid to teach young Americans how to think like Americans, Reid’s thought continued to shape America profoundly for a long time after the founding.

The story of the Scots and the founders has been largely forgotten today. The tragedy of that forgetting inspired me to write the book Common Sense Nation: Unlocking the Forgotten Power of the American Idea. Doing so, I felt, was my patriot duty and joyful obligation.