“What a piece of work is man,” says Hamlet. “How noble in reason, how infinite in faculty, In form and moving how express and admirable, In action how like an Angel, In apprehension how like a god . . .”

Hamlet is right that possession of such properties as reason, apprehension, and the capacity to act confer on humans a moral weight, a nobility, dignity, or inherent worth that makes what happens to humans important in an absolute sense.

What happens to humans can be a tragedy. What happens to rocks cannot. When we see pictures of atrocities, we understand that the victims were people like us, people who until their end possessed reason, apprehensions, personal unity, hopes, loves, and individuality as we do. That is what makes their deaths a tragedy and not, like the explosion of a lifeless galaxy, a firework. Gross metaphysical differences like those between humans and rocks imply gross moral differences.

Respectable Ethical Topics

If we turn to philosophical works on the foundations of ethics, the array of concepts is very different from talk of nobility, perfections, dignity, and tragedy. Those are found in classic literary texts. In ethical works, discussion is all about right and wrong actions, consequences and rules, rights and duties, virtues and dilemmas.

Those are all respectable ethical topics, but they are only central to ethics if we view it as fundamentally about what to do (how to live, what actions are right and wrong). That is a very partial view of ethics. It skates over the surface, by disconnecting what humans ought to do from what sort of entities they are. Its superficiality often leads to painting ethics in pastel shades, as if it were a polite and reasoned discourse about subtle questions, infused with little sense of urgency.

We need to go deeper and discover what ethics is really about. We can do that by tracking down what makes actions right or wrong, what are the origins of rights, duties, and virtues.

So why exactly is murder wrong? The fundamental reason why murder is wrong is that it is the (deliberate) destruction of something of great worth (rather than it is violating a rule, instantiating a vice, or subtracting from the greatest good of the greatest number). The reason for the rule “Thou shalt not kill” is that being killed is bad, and that is not about rules of action, it is about the evil of being dead. The very reason for the rule implies that it could have an exception in the case of self-defense. Whatever we decide in the end about the allowability of self-defense, the debate about it forces us to think about the reasons that lie behind the rules. Those reasons must be more ethically basic than the rules themselves.

Fundamental Human Rights

Or take the notion of rights (as in “fundamental human rights”), that plays such a powerful but contested role in political argument.

The concept of human rights has become a mainstay of objectivist views of ethics, and rightly so. The late 20th century saw two long-term trends in popular thinking about ethics. One was an increase in relativist opinions, with the generation of the ’60s spearheading a general libertarianism, an insistence on toleration of diverse moral views (for “Who is to say what is right?—it’s only your opinion”).

The other trend was an increasing insistence on rights.

The gross violations of rights in the killing fields of the mid-century prompted immense efforts in defense of the “inalienable” rights of the victims of dictators, of oppressed peoples, of refugees. The obvious incompatibility of those ethical stances, one anti-objectivist, the other objectivist in the extreme, proved no obstacle to their both being held passionately, often by the same people.

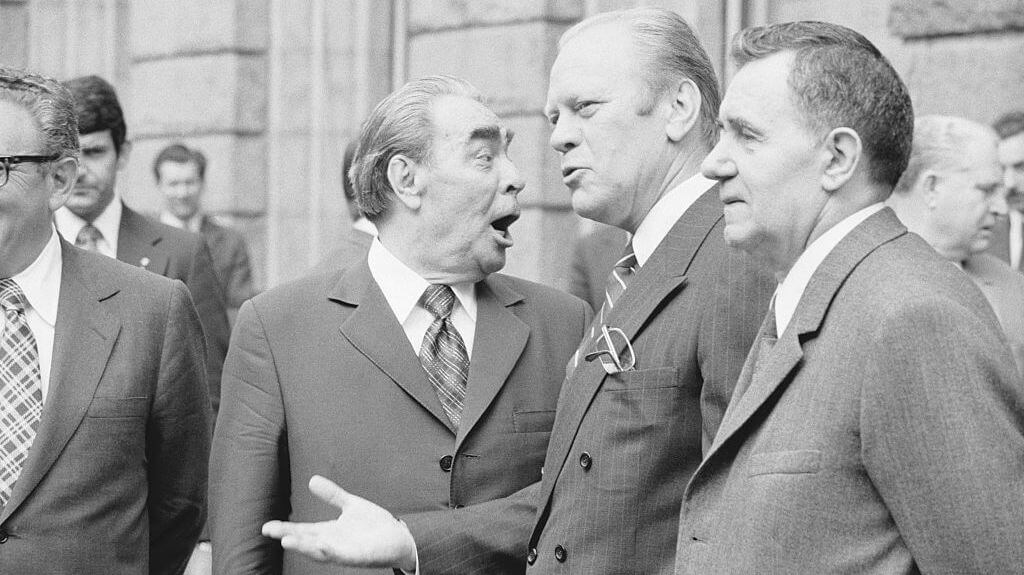

The account of the Helsinki rights movement in Tony Judt’s magisterial history of late-20th-century Europe, Postwar, demonstrates the huge power of rights as a moral and political weapon in the major historical event of the late twentieth century, the fall of the Soviet empire:

In August 1975 the Helsinki Accords were unanimously approved and signed [between the major Eastern and Western countries]. On the face of things, the Soviet Union was the main beneficiary of the Accords. . . . it was agreed that the ‘participating states will respect each other’s sovereign equality. . . .’

But also included . . . was a list of rights not just of states, but of persons and peoples, grouped under Principle VII (‘Respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms, including the freedom of thought, conscience, religion or belief’) and VIII (‘Equal rights and self-determination of peoples’.) Most of the political leaders who signed off on these clauses paid them little attention—on both sides of the Iron Curtain it was generally assumed that they were diplomatic window dressing, a sop to domestic opinion, and in any case unenforceable. . . .

It did not work out that way. . . . From this wordy and, it seemed, toothless list of rights and obligations was born the Helsinki Rights movement. Within a year of getting their long-awaited international conference agreement, Soviet leaders were faced with a growing and ultimately uncontrollable flowering of circles, clubs, networks, charters and individuals, all demanding ‘merely’ that their governments stick to the letter of that same agreement. . . . Hoist on the petard of their own cynicism, Leonid Brezhnev and his colleagues had inadvertently opened a breach in their own defenses. Against all expectation, it was to prove mortal.

Reference to rights serves as a reminder of how strongly most people are committed to objective ethics—most people believe that basic rights cannot be overridden by anyone’s decision (even, for example, a majority decision of a parliament). Healthy legal systems act to protect rights from violations by powerful interest groups, including states. Less healthy polities disparage human rights as “Western values,” despite heroic attempts by some of their own citizens in defense of their rights.

The way appeal to rights works in political and legal discourse is as bedrock, as a moral notion of last resort. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights was so successful partly because it laid down rights without any explanation of where they come from. The Declaration did go so far as to say that “all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights,” but offered no philosophical explanation of why. In fact, that was because its drafters agreed on the rights themselves but failed to reach agreement on the source of rights. When the Lebanese Thomist delegate wanted God included and the Brazilian delegation suggested reference to man being made in the image of God, the Chinese delegate absolutely refused to consider any such Western metaphysical and theological extravagances, with the result that the origin of rights was left out entirely. In retrospect, that was fortunate, as it allowed the Declaration to be widely accepted. That makes sense politically, but not philosophically.

For surely rights are not basic. If rights are thought of as freestanding, as if they themselves could serve as a basis for ethics, they would deserve Jeremy Bentham’s jibe that they are “nonsense upon stilts,” since they would be anomalous entities not fitting into any wider theory. But reference to the worth of persons can supply an explanation of where rights come from.

The Use and Abuse of Rights

What is it about humans that means they have rights? We have a right to life because our lives are valuable, not vice versa. As Nicholas Wolterstorff writes, “The U.N. declarations are all dignity-based documents. All of them affirm or assume that human rights accrue to human beings on account of the dignity that human beings possess, the worth, the excellence, the estimability.” He adds that that must lead to a search for what it is about humans that gives them that worth or dignity.

The Helsinki Accords themselves say that human rights “derive from the inherent dignity of the human person.” The rights of the Universal Declaration, such as the right to education, refer to the human beings for whom those goods are necessary. Humans have a right to education because they have the rationality to be educated, while animals don’t. That is a fact about humans, necessary and sufficient to support the right to be educated. Simply being human is sufficient and necessary to possess a right to life, because the worth of humans is what places a moral barrier in the way of any attempt to destroy human life. If there were no such thing as the worth or dignity of humans, there would be no purchase for the concept of rights; there would be nothing about humans in virtue of which they would deserve rights.

It is true that the prevalence of rights talk has led to certain justified complaints about the overuse of the notion. The language of rights has been subject to “strong inflationary pressures on the term that have brought about its debasement,” and thus often co-opted for political purposes so as to support a great range of implausible claimed entitlements. Books such as Aaron Rhodes’ The Debasement of Human Rights and Mary Ann Glendon’s Rights Talk: The Impoverishment of Political Discourse detail the extent to which rights talk has been expanded and misused. Those hijackings are a tribute to the inherent political power of the idea of rights. They are not good reasons for doubting the whole idea of rights.

Those misuses of rights talk highlight what is correct about the central notion of rights. What is valuable about rights talk is exactly that it focuses on the “recipient-dimension, the patient-dimension” of action, unlike, for example, obligation talk or guilt talk or virtue talk. “The reason the language of rights has proved so powerful in social protest movements is that it brings the victims and their moral condition into the light of day.” It sees actions or potential actions from the point of view of the person being acted on. Does the worth of that person, their inviolable dignity, place any limit on the proposed action? That is the first question to be asked, before any inquiry as to the place of the action in the moral code, or in the life of virtue or flourishing of the actor.

It is the same with the other general concepts prevalent in ethics, such as duties, rules, obligations, virtue, values, autonomy, liberty and the ethics of care. Just as with rights, a close examination shows that they make no sense without an underlying commitment to the worth of persons.

A Fine Sonata

If humans have an inherent worth or dignity, it should be possible to say what it is about them that gives them that worth. What is the difference between humans and stones that causes what happens to humans to be morally significant and what happens to stones not (or very little)?

It is possible to argue that worth is externally conferred, either by society or by God. That is not a likely theory as the absence of society or God would not seem to make any essential difference to what humans are. Perhaps it is essential to humans that they are social and religious beings, but that itself is what they are inherently like and contributes to their worth, not any external conferring.

It is also possible to argue that worth is not due to any inherent properties at all but is just a “commitment” of ours. There is widespread in the ethics world a “metaphysics-phobia,” shared by thinkers such as John Rawls and Ronald Dworkin, that avoids looking at the nature of humans as a source of ethics. But surely, as Wolterstorff puts it, “Worth or excellence or dignity is not something that just settles down here and there willy-nilly. An entity has worth on account of some property it has, or some capacity it can exercise, or some activity it has performed or is performing, or some relationship in which it stands. Its worth supervenes on its properties (capacities, activities etc.) or standing in certain relationships.” As he argues, “If the piano sonata that you composed is a fine sonata, then there’s something about your composition that makes it fine. We may find it difficult if not impossible to put into words what that is; but it makes no sense to say that it’s a fine sonata but that there’s nothing about it that makes it fine. The project of accounting for the worth of something is the project of identifying that about the thing on which its worth supervenes, the project of identifying that feature of the thing by virtue of which it has its particular worth.” There must be some story to tell. If there isn’t, there’s no account of what we recognize, or how we recognize it, or why we should react to what has worth differently from how we react to what doesn’t.

So if humans have worth-conferring properties, what are those properties?

A classic answer to the question “What gives humans worth?” is “rationality.” “Man’s excellence,” says Saint Augustine, “consists in the fact that God made him to His own image by giving him an intellectual soul which raises him above the beasts of the field.”

It is a good answer, but a partial one. One reason why this answer is prima facie attractive is that it is the most obvious difference between ourselves and animals. The worth of animals, on the face of it, is less than ours, and that appears due to their lack of a full version of rationality since they resemble us closely in so many other respects. Conversely, too, we value especially those animals like cats which are highly cognitive and inquisitive, and so have a trace of some kind of rationality. That is a large part of what makes them attractive as companion animals. If animals really did have the rationality attributed to them in anthropomorphic animal tales, we would not eat them, and we would treat them as real colleagues.

Rationality and the Good Will

Logical, ethical, and aesthetic matters are all realities to be recognized, and the unified cognitive ability, the rationality, to do so is essential to being human. That is central to and distinctive of humanity (but possibly shared by gods). We may conclude that a purely intellectual rationality is an essential part of what gives humans worth, even if not the whole story.

But the human person restricted to its rationality is autistic and not sufficient in itself to be the whole basis of the worth of persons. The first prominent thing it leaves out is the core of truth in Kant’s dictum that the only thing good unqualifiedly is the good will. A good will is not “rationality.” It is a commitment. And as literary and psychiatric people have said at length, an exclusive focus on rationality omits the crucial emotional aspects of humanity. Understanding reasons and motivations for action and choosing to act on them are central to “the distinctive endowment of a human being” that John Stuart Mill sought.

One extra thing needed is a unity of the self, where a person sees itself as a coherent unity that is “going somewhere” in life and makes rational decisions to get there. The mental contents of a person (at a time) have a unity that the mental contents of ten people in a room do not have. That unity is necessary for agency; for example, a person’s conflicting motives or reasons for a course of action are not separate thoughts that are balanced like weights, but are brought together and compared in some unified faculty. Agency also needs memory and imagination of the future—of my past and my future. It only makes sense for me to consider an action if its effect in the future bears somehow on my larger plans. There must be some point to the action and its effects in the light of my wish for survival, or eating, or tenure, or love for some others, or some other project; those projects themselves only making sense in a life narrative that is to some degree coherent. I must indeed perceive myself as having some degree of worth; otherwise action in pursuit of my plans is pointless (unless I have to an extreme degree a defect of self-perception such as self-loathing or servility).

A solid sense of “personal identity” is needed for moral concerns, such as a feeling for the boundary of the “I” to whom I hope to prevent harm, concern for how I will get through tomorrow, or shame for or pride in what I did earlier. It is because that person will be or was me, and I know that, that I can have such moral concern.

As literary people (more than philosophers) have emphasized, emotions are also crucial to being human. it is impossible to be human without an adequate development of the emotions. Even to devote oneself to an activity that is wholly reason, like pure mathematics, one needs a passion for doing the hard work.

Love Thy Neighbor

One emotion (if that is the right word) is crucial: love. An obvious single serious lack in humanity is an inability to (or lack of wish to) love. If extreme, that is something that truly goes to the heart of what it means to be human. Some defect in that area is no doubt near-universal, but a serious defect means something missing from the core of humanity.

One indication of its importance is the credibility of Jesus’ “Euclidean” claim, that all the requirements of the law follow (logically) from just two axioms: Love God, and Love thy neighbor. Loving one’s neighbor implies both wanting his good and taking action to achieve it, which rules out causing harm and commands benevolence. Jesus’ parable of the Good Samaritan is a favorite of both believers and non-believers because it goes directly to the point of moral action—the traveler injured on the road has no claims on the passers-by except being a human in need. Moral obligation arises from the worth of the person in need, combined (not with any social or legal ties) but solely on the Samaritan’s ability to do something about the need.

The human person is very complex, and that is essential to his worth. His rationality, his mental unity (and diversity), his ability to act freely for reasons, his individuality, and possibly his being embodied, are all part of what sets humanity off from the rest of creation. It is what makes a human death a tragedy, and would make the extinction of the human race a universal catastrophe. The view found in some “deep ecology” circles that the human race is a pest and its extinction would be a net benefit to the universe is profoundly disturbing.

The point of view taken in The Worth of Persons is to look at the worth of humans (and other parts of the universe), in abstraction from questions of right and wrong action. It prioritizes axiology (the theory of what is inherently valuable) over casuistry (the theory of which actions are right and wrong). But of course the fact that humans have worth (which itself has nothing to do with action) does have consequences for action. The worth of persons is the foundation of ethics in the sense that it is possible to derive truths about what ought to be done from the worth of persons.

In the simplest case, the fact that persons have worth means that their destruction is a bad thing in itself (as it removes something good from the universe). Hence it is wrong. “Thou shalt not kill.”

It is possible that killing might in some circumstance prevent more killing, as in the classic case of self-defense. In that case, a forced choice between killing an assailant and allowing oneself to be killed pits worth against worth. Calling on the worth of persons does not resolve the dilemma. It explains why there is a dilemma in the first place. That is what foundations of ethics are for. Their purpose is not to lay down exceptionless moral rules or to resolve ethical dilemmas. Their purpose is to explain the purpose of rules in general and to explain the moral weight on both sides of dilemmas.

The Morally Thin Analysis of Lying

To see, however, the difference it makes to found ethics on the worth of persons, we can look at a moral question that is not as simple as explaining why murder is wrong. Why is lying wrong (usually, but with possible exceptions)? If persons have worth, it is obvious why killing them is bad, but it is far from clear what implications there are for the wrongness of an action like lying. How does that necessarily offend against the worth of persons?

In certain cases, it obviously does. Harm does typically arise for the one deceived by a lie and there are consequences of the degrading of trust generally. Kantians also rightly object to the violation of the autonomy of those lied to, which improperly takes away their control over their own lives and decisions and so manipulates them. Those are all direct violations of the worth of the persons lied to.

But those analyses also miss some of the point. The lack of a worth-of-persons perspective has led to analyses of lying being morally thin and out of contact with the direct revulsion we feel for it. As Aristotle puts it, “falsehood is in itself mean and culpable, and truth noble and worthy of praise.” He continues, “For the man who loves truth, and is truthful where nothing is at stake, will still more be truthful where something is at stake; he will avoid falsehood as something base, seeing that he avoided it even for its own sake.” That is not about either consequences or autonomy. It is something more direct.

The basic reason for loving truthfulness and abhorring lying is the rationality of persons, which, as explained above, is one principal basis of their worth. Surely there is something to be said for the idea that the point of the cognitive system is to be aligned with the truth, as far as possible, and hence that making it serve falsehood is a perversion that is unworthy of its dignity and its role in human life.

We are inclined to think of people jailed for fraud, “You’re only on the planet once, what are you doing wasting your life and your intelligence deceiving people?” If we are forced to lie, as in the classic case of misleading a would-be murderer on the location of a knife, that is the right thing to do, certainly—anything else would be collaborating with an assault on a person. But it still does a kind of violence to the cognitive system—indeed, the point of the example is the need for a very serious reason to overcome the natural orientation of the system to the truth. Cognition is integral to being human, not just a tool in the service of consequences or autonomy, which is why the notions of perversion and violence apply.

Rationality is part of what constitutes human worth. Its exercise, which includes finding the truth, is therefore a perfection of human worth. As humans are social beings, the communication of discovered truth is also a perfection of human worth—it is part of communal rationality. So deliberately doing the opposite is a degradation of human nature and is morally revolting. That is so prior to and irrespective of any harms or violations of autonomy that may or may not ensue.

The example of lying shows how founding ethics on the worth of persons gives a different perspective on ethics (that is, ethics in the sense of deciding on what to do). On the one hand, it sees the worth of persons as a moral limit to what can be done to them—human rights such as the right to life are just the worth of persons from the perspective of those with the potential to damage it.

On the other hand, persons being what they are, such as rational, are perfectible and deserve, where possible, the resources to achieve their perfection. Humans have a right to education, for example, just because they are rational and it is a fact of life that rationality develops gradually and with effort and external input. Other aspects of humanity on which its worth depends, such as emotional structure and individuality, likewise need protecting and developing—that is, it is morally required to develop them, a requirement that holds both on the self and on others in a position to help.

The leading ideas of the theory of ethics developed in The Worth of Persons are:

- Ethics in the sense of what to do follows from something much more basic, the worth of persons.

- The foundations of ethics should not be approached with a phobia about metaphysics; beings that matter ethically, like humans, are inherently different from ones that don’t, like stones. It is possible to say what the difference lies in.

- The point of ethical foundations is not to produce principles to decide difficult questions of what to do, but to explain why difficulties arise.

- Essential to ethics is the Aristotelian notion of a human perfection or excellence.

- Humans are in contact with and subject to an ethical realm in the same way they are in contact with and subject to a realm of logic and evidence. The evidence in a court of law is strong or not and the jury’s role is to evaluate which. Ethics is objective in the same sense.

- The worth of persons is doubtfully compatible with a purely materialist view of the universe, but what alternative cosmology is sufficient is not easy to say.

Each of these is a minority position in contemporary ethical theory. The combination is unique.