Vaclav Havel observed that the totalitarian is himself trapped within his own web, and the regime is captive to its own lies. He’s stuck in a never-ending loop. Since everything is “hidden beneath a thick crust of lies,” Havel wrote, “it is never quite clear when the proverbial last straw will fall, or what that straw will be. This, too, is why the regime prosecutes, almost as a reflex action preventively, even the most modest attempts to live within the truth.” So they have to falsify everything: the past, the present, the future, statistics, everything.

In the end, the regime “pretends to persecute no one. It pretends to fear nothing. It pretends to pretend nothing.”

Any reference to the truth by the little guy threatens the utopian house of cards. The tyrant’s monomania also renders him unsuitable for real conversation and actual debate. So, perhaps it is the control freaks themselves—trapped within their own web of lies—who are the most fearful of social isolation, most vulnerable to the weaponization of loneliness. This could explain why so many celebrities are utter slaves to political correctness. Or why radical revolutions so often end up eating their own.

In the meantime, however, tyrants are obsessed with building armies of people who will follow their lead and bring others into the fold.

Six Patterns of Totalitarian Behavior

Conducive to Mob-Building

If you are trying to discern whether a leader is afflicted with a totalitarian impulse, look for six particular behavioral patterns. They include meddling, lawlessness, projection, abuse of power, lack of empathy, and constant but effective lying. All these patterns of manipulative behavior support the mobilization of mobs. If these patterns gain strength, they lay the groundwork for a destabilized society in which people are more atomized, more fearful of not conforming, and more needy for authentic human connection.

First, the totalitarian is a meddler, as well as a mobster. He feels entitled to control the lives of others, to control their speech, their thoughts, and their relationships.

As philosopher Eric Hoffer observed, “A man is likely to mind his own business when it is worth minding. When it is not, he takes his mind off his own meaningless affairs by minding other people’s business. This minding of other people’s business expresses itself in excessive gossip, snooping, and meddling, and also in feverish interest in communal, national, and racial affairs.” Indeed, this all adds up to the essence of a surveillance state.

Social engineers may give lip service to the idea of a rule of law, but that would be for others to obey their laws. The rule of law is only serviceable until they gain the power to abolish it and then dictate the law at whim. Agitator-propagandist Saul Alinsky clarified this point in Rules for Radicals, where he stated the agitator should “make the enemy live up to its own book of rules.” He meant that they should use the goodwill of America’s middle class against it—including its belief in rule of law and fairness—while not being beholden to any such rules themselves. Manufacturing and manipulating a sense of guilt in people neutralizes any potential dissent and renders them passive so that Alinskyan social control can dominate under the pretense of social justice.

Psychological projection is another common pattern of social controllers. Jacques Ellul described this projection as an element of propaganda: “Hate is generally its most profitable resource . . . it consists of attributing one’s misfortunes and sins to ‘another,’ who must be killed in order to assure the disappearance of those misfortunates and sins.” That mindset has been a prelude to many atrocities throughout history. But we can see its reflections in everyday life, too, from the toxic boss to the queen bee at a mega-sized high school that houses thousands of students.

Another pattern of behavior is the abuse of authority to exploit those in a less powerful or dependent position. In such cases of undue influence, the manipulator persuades others to agree to acts that they would not commit if they were exercising clear judgment. The manipulator uses his greater influence to recruit that person for the sole purpose of gaining power of some sort, be it money, sex, influence, status, or whatever.

The utter lack of empathy in these near-psychopathic actors is clear. We have seen how they enable criminal behavior. Undergirding it all is an attitude of deception, denial, and rationalization. When the honesty of others gets in their way, their reflex is, again, to try to compel reality to conform to their fantasies.

Deceit is second nature to tyrants. They use a host of manipulative actions to get around being called out on immoral behaviors. When exposed, they typically deny, ingratiate, pander, rationalize, project, and blame the victim. If there is evidence, they make a point of destroying it. If there are others who know about it, they find ways to hush them up, including through payoffs, blackmail, stonewalling, defamation, and even assassination. They are experts in slander, in assigning guilt by association, and making up allegations out of whole cloth.

The Mob in Action

Whatever form a mob takes, mobs always share certain key traits once they’ve been cultivated. They are aggressive, often to the point of violence. They act in concert as a herd. Perhaps the most dominant feature of mobs is that they don’t have the capacity for rational thought because, as decades of research show, individual members are usually only acting on their conformity impulse.

We saw this poignantly in the summer of 2020, when mobs wreaked nonsensical havoc on American cities. The mindlessness of the mob claiming to be anti-racist while angrily destroying black-owned businesses or tearing down a statue of an abolitionist is simply demonstrating its absurd nature. Its fuel is raw emotion. Identity politics would be of marginal value to activists without the ability to harness the emotion of grievance and then mobilize it.

The essential purpose of the mass movements of mobs is that they follow up propaganda with action. As Ellul notes: “Propaganda seeks to induce action with as little thought as possible . . . action must come directly from the depths of the unconscious; it must release tension, become a reflex.” In cases of street theater, these actions are typically parades, demonstrations, rallies, street protests, and so forth. Various propagandistic techniques heighten the emotions of the mob, including chanting, marching, sloganeering, and scapegoating.

Mob sentiments, however, can show up in many nonstreet settings such as in classrooms, social media, or human resources departments at universities and in the corporate world. Support for mob activity can include orders, directives, contributions to a mob-approved “cause” by corporations, statements of support, “bias response teams,” and so on.

Group pressure that results from mob activity can enhance the effectiveness of the mob. That pressure can trigger a virus of social contagion—other mob actions—that serves the power-mongering elites and their propaganda. Mob activity can trigger participants to mimic the actions of others, even if those actions are barbaric. Looting, rioting, and even killing can come about through the contagion of crowds. In fact, a mob can descend quickly into action that is depraved beyond belief—from Antifa thugs beating up defenseless bystanders to Joseph Fouché, the Butcher of Lyon in the French Revolution, who entertained the mob by setting up poses with the beheaded bodies of his victims.

The critical point is that the mob acts as “one.”

Ideology is merely the tool, the cover story. It divides people into an in-group and out-group, like racists versus oppressed, rich versus oppressed, infidel versus believer, or, as mob organizer Saul Alinsky put it, “haves” versus “have-nots.” A demagogue hypes the narrative so that social contagion builds around it, attracting more members. Control of media platforms prevents any counternarrative from being heard.

As the mob goes into action, it enables and legitimizes the power grab for the demagogues, even as its members may believe they are marching for an ideology of social justice. The elitist activists who incite mobs also use the ideology and its narratives as cover for themselves.

The parallels to the processes of identity politics and political correctness are apparent in many aspects of this mob-building. Often, being part of a mob seems simply an extension of a person’s newly assigned identity, as “victim” or “ally” or “social justice warrior.”.

Mobs act a lot like gangs or cults. And, as cult expert Margaret Thaler Singer noted, the only real goal of cults is to grow their membership and the power of their leaders in perpetuity.

They recruit from the ranks of people who are looking for purpose. These can include very educated people whose skills and knowledge can help grow the mass, as well as those who are lonely and vulnerable in society. People with a healthy skepticism, who have strong relationships and a sense of purpose, are not nearly as recruitable.

Six prime ingredients set the mob in action: a malady, a cure, an enemy, an ideology, a sense of urgency, and a monopoly on narrative. Let’s look at each ingredient.

The Malady: Atomization and Alienation

Hoffer neatly described mob formation as a process that “aims to infect people with a malady and then offer the movement as a cure.” On the surface, the “malady” is usually posed as a social injustice that needs to be addressed. For example, marching mobs in 2020 framed George Floyd’s death as symbolic of a malady of “systemic racism” for which the cure was defunding the police. There are many more examples, such as marches for gun control, world peace, or saving the planet from climate change.

But are such narratives really what motivate people to immerse themselves in street mobs? Are they really what motivates a human resources bureaucrat to get people fired due to suspicion of a thought crime? I propose that the malady at the root of mob formation runs much deeper. It comes from a sense of alienation within the psyche of the individual who wants desperately to be a part of something. He wants to be part of an in-group, often associated with the slogan of being “on the right side of history,” the group that will cure the supposed malady of social injustice. It’s a combination of alienation and the yearning to belong that is the true malady that sparks mob members into action.

Sure, people can march sincerely for slogans like “save the planet” and “Black Lives Matter,” but the biggest draw is the crowd. Attraction to it comes from a feeling of being atomized, not bonded with others, and lacking a sense of true identity. That’s a dysfunctional condition. If people lack a sense of personal connection through family, faith, or friendship, they’re going to be more adrift and susceptible to joining aggressive mobs with all the social pressures that go with them.

Political correctness and identity politics play big roles in cultivating that sense of atomization. According to Ellul, “to be alienated means to be someone other (alienus) than oneself; it can also mean to belong to someone else. In a more profound sense, it means to be deprived of one’s self, to be subjected to or even identified with someone else.” Alienation can also come from not having a sense of virtue or not acquiring useful knowledge and wisdom. I don’t believe a psychologically healthy person can look at the mugshots of Antifa members without detecting profound alienation in their faces.

No matter what banner a mob marches under, they are seeded by individuals who tend to be seduced by the lure of the crowd as a remedy for a sense of social isolation, regardless of where that feeling is coming from.

The Cure: Belonging

“The ecstatic participation in mass elation is the oldest psycho drama in the world,” wrote Joost Meerloo. If people are drawn to mobs because they feel alienated, then filling that vacuum by becoming a part of the mass seems to offer them relief and a sense of euphoria. In Nazi Germany, massive crowds gathered to march under the banner of fascism, while in 2020 America, crowds rioted under the claim of antifascism. Both promoted violence and viewed people of certain demographics as lesser beings. Either way, the internal psychic dynamic was the same: a desire to become a part of a group, especially one that seemed to be gaining social approval or of being protected by power brokers.

Mob and cult members get great pleasure from the feeling of being love-bombed by an approving crowd and media. The mass offers an identity, often that of an oppressed victim or “ally” of the victim. But it’s also the identity of a superior being, a hero who fights for the oppressed, megaphone or placard in hand. Communists have long beckoned individuals to join and take on the identity of heroic comrade-in-arms who fights for the revolution. Mob antics such as street blockades or shouting down a perceived enemy can give participants an exhilarating feeling of power they have never felt before. In the crowd, they can try to live out a heroic fantasy that they would never attempt alone.

So the mob offers a combination of anonymity and closeness to other people that is often irresistible. Nobel laureate Elias Canetti analyzed this feeling of being “touched” by others. In his 1960 book Crowds and Power, Canetti identifies a moment in the formation of a crowd he calls “the discharge.” He describes the discharge as a mass feeling of being equal. It gives participants a sense of relief, of having thrown off whatever differences they have with others. In a similar vein, Havel observed that all of us seem to have “some willingness to merge with the anonymous crowd and to flow comfortably along with it down the river of pseudo-life.”

That feeling is an illusion. As Canetti notes, crowds must keep forming and repeating the process, must keep growing and seeking new members in order to continue the illusion of that discharge, that aspiration for total equality. In the end, we are all individuals, and the mass of humanity as a grand collective is not truly attainable or sustainable.

But the utopian illusion persists. Propaganda continuously feeds it. The yearning to be a part of something bigger than oneself is natural, of course. But when it plays out destructively in a mob, it more resembles a feature of cults, as well as all movements aimed at building a collectivist utopia in which people get homogenized into an equality that is nonexistent.

The fact that alienation is the fuel for mob formation likely explains why our ruling classes seem to be so invested in isolating people. Who can doubt that the rioting Black Lives Matter mobs in 2020 were inflated by youth who had long felt alienated and perhaps were also tired of being forced to self-isolate because of COVID-19 lockdowns during the preceding two months? Who can doubt that the unhinged mob that often gathered around Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s home was whipped up through nonstop propaganda insisting their lives would be destroyed if the 50 states were allowed to pass their own legislation on abortion?

On a larger scale, who can doubt that elitist policies promoting family breakdown and state dependency fuel alienation throughout society? People from broken families and broken communities, especially youth, are likely to feel a yearning for the sense of energy and excitement that a mob—or a street gang or a cult—seems to offer.

The Enemy

Mass movements can rise and spread without belief in a God, but never without belief in a devil, according to Hoffer. And that devil has to be all-powerful and present everywhere. Identity politics is a means of creating the devil: the racist, the white supremacist, the transphobe, the oppressor. It ceaselessly stokes the us-versus-them dynamic. It also puts a face on the enemy so that the enemy can be defaced and dehumanized. As Saul Alinsky’s 13th rule states: “Pick the target, freeze it, personalize it, and polarize it.” The “personalization” here is really about depersonalization through the demonization of “those people.”

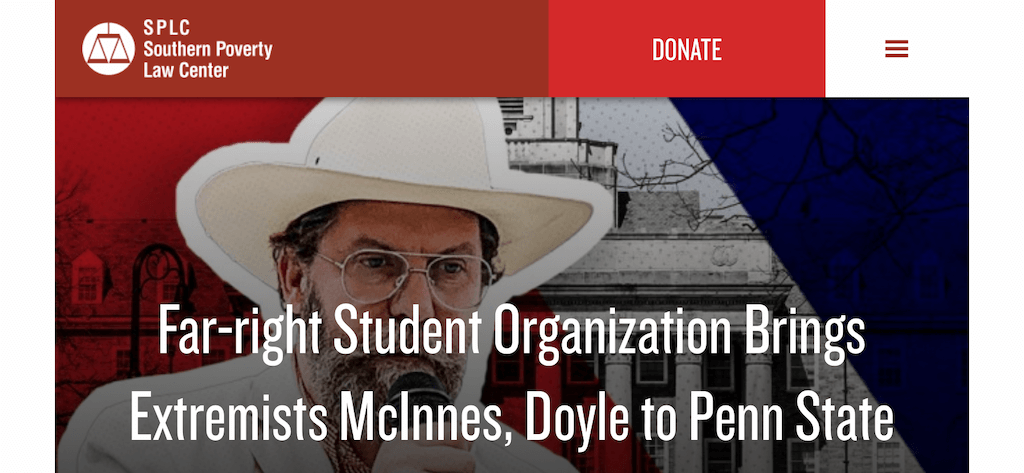

White racism and police brutality are good bogeymen, but they are a bit too abstract. Only individuals can be “canceled.” That’s probably why the Southern Poverty Law Center posts on its website humongous headshots of the people it selects as its targets. Fear is a central reason why there is no way out of this process.

Participants feel they have to signal their anger in order to avoid becoming marked as the enemy as well. For example, a former member of the “social justice industry” wrote in Quillette that he lost his job when he upset the wrong person. He said he became a “social justice warrior” because it was “exhilarating. Every time I called someone a racist or sexist, I would get a rush.” The rush was validated on social media with lots of “likes.” But, ultimately, “a fear of being targeted by the mob induces us to signal publicly that we’re a part of it.”

George Orwell described the phenomenon of that rush as “Two Minutes Hate” in his novel Nineteen Eighty-Four. Citizens of the dystopia took part in a daily ritual of ranting against “thought criminals” of the state who appeared on a screen. The novel’s protagonist, Winston Smith, explains: “The horrible thing about the Two Minutes Hate was not that one was obliged to act a part, but that it was impossible to avoid joining in.” He describes how a hideous ecstasy would follow and how the rage could easily be switched from one object to another.

Mobs are padded by recruitment of so-called allies to join them in the fight against whatever injustice is being touted. Hoffer had an interesting point to make about this process: “We do not usually look for allies when we love . . . But we always look for allies when we hate.” Indeed, the term “ally” is very common among players of the divisive game of identity politics, which revolves around sustaining the image of an enemy and stoking the hate that goes with that image.

Ideology, Cause, and Utopia

Again, ideologies serve propaganda, not the other way around. Propaganda actually destroys doctrines and ideologies, replacing them with chain thinking and conditioned emotional reflexes that serve an agenda. Yet ideology is a critical prop for energizing a mob.

Abuse of language is an essential tool for doing this. All totalitarians rely on sowing confusion by subverting the meaning of words. Orwell examined the phenomenon in his essay “Politics and the English Language,” where he noted that the corruption of language leads to the corruption of thought. The dystopian society in his novel Nineteen Eighty-Four went so far off the rails that it celebrated slogans like “freedom is slavery” and “war is peace.” In like manner, radical utopians today spread thought-numbing expressions like “words are violence.”

One of the most glaring perversions of language is the enforcement of pronoun protocols to avoid “misgendering.” They are very destabilizing to the thought process because pronouns serve as structure or scaffolding for language. Linguists have referred to pronouns as function words, unlike other parts of speech such as adjectives or nouns. So if you undermine the structure or function of the language in such a fundamental way, then you can implode the process of thought. The numerous institutions that have instituted such policies are feeding social dysfunction and softening the ground for mob-making.

As individuals are influenced through propaganda, groupthink takes hold. A mass starts to form. This is not a conscious process, but a matter of grooming people as mercenaries for the cause by instilling reflexes and habits through sloganeering and chanting, through images in popular culture, the media, and in schools. Myth-building is especially useful in ideologies that come with a vision of utopia and the perfectibility of man. All this nudges action, modifies behavior, and stirs up blind emotions.

Ideologies are especially related to identity politics. When people integrate themselves into agitating crowds and mobs, they conform to roles based on group identity above any individual identity. They must see themselves primarily as advocates of the ideology—environmentalist, feminist, socialist, “antiracist,” or whatever—so that they conscientiously conform in every detail to the purported goals and values of the group. They often become enslaved to that identity once they are committed to it as a place of belonging. To risk holding a taboo opinion is to risk isolating oneself from the collective and signaling yourself as its enemy.

People are often drawn to the ideology through a preexisting sense of fairness or justice. But the mob pushes them into accepting distorted definitions of fairness. Goalposts move unexpectedly. Hence, a protest against a single case of police brutality morphs into a call to abolish all law enforcement. This may not be what certain mob members originally signed on for, but they are swept along by the machinery.

Once the machine is in control, Ellul notes, “there can be no objection to it by those who adhered to the previously prevailing ideology . . . People live therefore in the mental confusion that propaganda purposely seeks to create.” Even if a member wants to reconsider previous views or reestablish a friendship that was discarded when they joined the mob or cult, pride often gets in the way. He is invested. This process reflects, though perhaps in a milder way, the initiation rite of a gang or cult, particularly the more gruesome rites that a terrorist might require of an initiate, such as performing a rape or an execution. Once the deed is done, the new identity is cemented. There is no turning back in the mind of the initiate.

The propagandist can take one of two paths when using ideologies to fit agendas: “either stimulate them, or mythologize them,” as Ellul put it. Stimulating an ideology is often done through sloganeering, using an image or idea that is anchored in popular consciousness, in order to bring out the desired reflexes in people. Slogans that evoke ideals of equality, justice, peace, and love never fall out of favor. And sometimes, the attempt to convert can be as simple as having an anti-American speaker stand in front of the American flag or wear a flag pin, which camouflages the speaker’s actual intentions and portrays him in the opposite light.

Urgency and a Sense of Crisis

In his 19th-century study of mobs, Gustave Le Bon wrote, “when the structure of a civilization is rotten it is always the masses that bring about its downfall.” In observing the connection between utopia and terror, eminent historian Vejas Liulevicius notes that masterminds of chaos have “always exploited societies in turmoil, full of uprooted and atomized individuals.”

So, the fundamental transformation of a society is fastest when a sense of crisis can overwhelm its atomized members with fear and panic. The truth of a mob’s claims that they’re fighting a “crisis”—whether it’s a climate crisis or a gun control crisis or anything else—is secondary. The primary goal is always to cultivate a sense of urgency. The earth is dying—in your lifetime! The unvaccinated and unmasked are going to kill us all! Without unrestricted abortion up to (and beyond) the moment of birth, women forever will be enslaved by the patriarchy!

Ruling elites in our institutions and especially in the media clearly stoke this sense of urgent crisis to elicit the fear and emotion that can push a mob into action. And those who lead the charge would never let any crisis—real or manufactured—“go to waste” because the panic evoked by crises is the lifeblood of mob mobilization.

Monopolizing the Media

A media monopoly can orchestrate a blackout of any news the mob organizers do not want people to digest or think about. It can then direct the focus of untold millions so that they fulfill the agenda. If the media say something is an issue, it is an issue. If they say something is urgent, it is urgent. If they say something is a crisis, it is a crisis. If they say there is nothing to see here, move along, they require the audience to shut up.

As influence guru Robert Cialdini notes, “What’s focal is causal.” This sums up the ultimate purpose of propaganda, which is to move people into action for the agenda. When advertisers and propagandists direct our focus in order to direct our thoughts, our speech, and our behavior—to the utter exclusion of everything else—we tend to respond in kind.

Hence, the media describe violent rioters who attack police officers in Chicago or mobs who swarm the home of a Supreme Court justice as “peaceful protesters” exercising their First Amendment rights. At the same time, the media portray children not wearing masks in school as “selfish jerks.” Having a media monopoly is essential to such illusions that can feed public opinion and, therefore, can empower the mob mindset and secure the perches of elites.

Such mass delusions have been with us for a long time, though never on the global scale made possible by the internet. In the past, they have been confined to regions, such as the Salem witch trials in 17th-century Massachusetts or the mania over the value of tulip bulbs in 16th-century Europe. But with the internet as a tool of media, mass delusions can go global, which is why we seemed to return to superstition as a substitute for science when it came to the fear of being less than the magical “six feet” of distance from someone to avoid COVID-19 infection, or wearing a mask even while swimming alone in the ocean.

Such phenomena are related to the theory of memetics introduced by Richard Dawkins in his 1976 book The Selfish Gene. Dawkins suggests that memes—or ideas—could replicate in the same way that genes do in genetics and thereby cause huge psychological changes in the culture at large. As with an availability cascade, it doesn’t matter how far-fetched an idea is. If it is repeatedly injected into public discourse by a controlled media that suppresses any other ideas, it can induce social contagions that change the culture quickly.

For example, in the 2010s, it had never occurred to 99 percent of Americans that biological sex could be something arbitrarily “assigned at birth.” Yet, practically overnight, the idea was institutionalized into a mob mindset via media control by those pushing the agenda. A fast and furious propaganda campaign that had already begun in the media, popular culture, the corporate world, legislatures, Hollywood, medicine, academia, K–12 education—and even some churches and the military—dug in its heels. It went global, even pushing gender ideology on developing countries whose populations were baffled by it.

Totalitarian forces can induce emotional responses in people—especially through fear-mongering—to spur them into action as a mass. Identity politics and political correctness are prime ingredients in the making of mindless mobs, whether it’s a street mob, a social media mob, or simply a mass of compliant bystanders who conform to the agenda and enable it without question.

It’s Critical to Distinguish Between

Astroturfed Mobs and Organic Protests

Not all protesting crowds are mobs, however. This is an extremely important point. Many protests and rallies occur in reaction against totalitarian forces that oppress people and seek to squash freedom of expression and invade our private lives. The key differences between a true protest and mob agitation are the promotion and enactment of violence as well as the group’s level of agreement with an enforced propagandistic narrative.

Especially in the 20th century, we can consult history for cases of people who gathered peacefully, at great peril, often risking brutal imprisonment or even death for challenging the narrative of the propaganda. One example was the mass rally for freedom from totalitarian rule during the Prague Spring in 1968 Czechoslovakia. Another was the democracy movement in Tiananmen Square in 1989. Yet another was the 2019 protest movement in Hong Kong in which as many as two million—a quarter of the special administrative region’s population—filled the streets to object to growing communist heavy handedness from Beijing. People who protested against vaccine mandates in 2021 and 2022 also took great risks, especially in places like Australia, New Zealand, Germany, and Austria, where clampdowns were draconian and brutal.

When authentic mass protests form in oppressive societies like the communist regimes of China or the theocratic dictatorship in Iran, or even in a supposed democracy like Australia in 2021, they do so organically and spontaneously. By contrast, in the so-called free world in 2020, we saw more astroturfed mobs. Those mobs were organized and orchestrated by special interest groups flush with cash and propped up by media support, such as the Marxist BLM movement that has ties to power-mongering elites all over the world, including Venezuelan strongman Nicolas Maduro and the Chinese Communist Party.

In the West, astroturfed protests tend to be celebrated by the corporate media. They get lots of celebrity support and corporate sponsorships. Hence, the participants are not concerned with personal risk. Rather, they often get the social reward of media praise. This contrasts starkly with the more oppressed movements for freedom under totalitarian regimes in which the participants are smeared by media talking heads and canceled by Big Tech and arrested by authorities.

Astroturfed marches can look like parades, often generating a circus-like atmosphere that beckons others to join in. They can also be riots in which police are told to stand down. Either way, those in the mob usually feel sanctified in doing outrageous things, like the middle-class white women who felt free in the company of Black Lives Matter mobs to spit lectures at black police officers and call them racists. Fat chance they’d try similar things in a totalitarian system like China’s.

Organizers of these top-down movements can build a crowd with the glitter of superstar celebrities who lend their names to the causes. For example, during the march of the “pussy hats” after the inauguration of Donald Trump in January 2017, pop star Madonna could say without any fear of retribution—as would come down on her hard in an authoritarian society—that she thought a lot about “blowing up the White House.” Hollywood celebrity Alyssa Milano played a similar role with her visible support for the 2018 protests that disrupted the hearings of the Senate Judiciary Committee on the nomination of Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court.

At the same time, elected officials can lend their authority to mob action. This was the case when Portland’s mayor permitted Antifa mobs to set fire to the police station and to attack the federal building there, throwing objects and incendiary devices and even using lasers to blind some officers deliberately and permanently (which they succeeded in doing).

In the end, the three processes—identity politics, political correctness, and mob formation—are deeply interconnected and self-reinforcing. Central to all of them is the manipulation of the fear of isolation. While these processes are all closely related and usually simultaneous, they are distinct. They act in different ways on different groups of people. Each plays a role in the process of inducing a free people to self-censor, self-isolate, give up their own freedoms, and then submit to totalitarian rule.

The irony is that our compliance with these forces does not relieve us from isolation, as many hope for and expect. Rather, our compliance only drives us further into isolation and cements our atomization. In turn, this atomization feeds a growing desire for human connection. When people feel stuck in that vacuum of social distrust and confusion, they yearn to get out.

As we have seen, political correctness and identity politics are used to divide individuals into groups and pit them against each other in certain segments of the American population. Totalitarians are ever eager to use the emotional vacuums they manufacture to activate the mobs who serve their bids for power.