A French exit, as they sometimes call it, is synonymous with “ghosting.” One simply disappears, without farewells. Detroit was once one of the top four cities in the country, and the very top in standard of living, home ownership, manufacturing, entertainment, aviation, mobility, and consumer innovation. It is the only case I know of a major American city that ghosted, disappearing without saying goodbye. This is that story, or the part I can remember.

Boom and Bust French

According to Aristotle the city comes together for the sake of living but continues to exist for the sake of living well. Detroit has its own twist on this observation, having been founded for the sake of the French habit of living well or, at least, dressing well. French trappers and traders first moved into the region around the Great Lakes where beavers thrived after the demand for hats, first popularized by Louis XIII of France, led to the disappearance of European beavers.

Louis XIV in 1685 issued the Edict of Fontainebleau, revoking nearly 100 years of religious tolerance for French protestants, or Huguenots. With the expulsion of the Huguenots complete, French protestants found themselves in colonial New York (e.g., New Rochelle), among other places, and like their British American counterparts, permanently settled there in the interest of religious liberty.

But French Catholic settlement was different. Having no interest in religious liberty, many French men came to North America without families, intending to return to Europe rich from trapping. By the turn of the 17th century, traders periodically accumulated surplus pelts around Michilimackinac, a trading post and fortress situated at the intersection of Lac des Michigami (Lake Michigan), Lac des Hurons (Lake Huron) and Lac Superieur (Lake Superior). Price volatility undermined French settlement in the region, as the vigor of settlements went up and down with the volatility of fur prices.

To protect the boom-and-bust French settlements from the encroachment of the more stubborn sort of British settlement, Louis XIV commissioned his Minister of Marine, compte de Pontchartrain, to establish a permanent, self-sufficient—which meant farming—settlement in the region of the Great Lakes.

Pontchartrain turned to Antione de La Mothe Cadillac, an experienced new world adventurer. Cadillac recruited 100 people—roughly 40 families—for the new settlement. Surveying the geography, Cadillac chose an advantageous spot on the strait of Lake Erie or “le detroit du Lac Erie.” There, in 1701, Cadillac founded Fort Pontchartrain du Detroit. My paternal grandmother was a descendant of Joseph Parent, a blacksmith and head of one of the 40 families that first settled Detroit. The majority of my cousins on my father’s side descended as well from Paul L’Anglois (a last name signifying Norman of English extraction), another of the first Detroiters.

In 1760 after the defeat of Montreal in the French and Indian War, the French turned Fort Pontchartrain over to the British, who truncated the name to Detroit, and changed its pronunciation from “day-twah” to “duh-troyt.” The French had maintained good relations with the natives of North America, in no small part because French fortune-seekers often did not bring wives to the new world, and so intermarried with indigenous people.

The relations of the less romantic British with native Americans were poor, and in 1763 an Ottawa chief named Pontiac, with cautious support from disgruntled French Detroiters, rallied several tribes to war against the British in what is known as Pontiac’s Rebellion. Pontiac laid siege to Detroit, without success, and skirmished in the surrounding lands. At my ancestors’ ribbon farm, Parent Farm, Pontiac’s braves surprised the British, killed 20 of them, and left the dead in Parent Creek. Ever after, Parent Creek has been Bloody Run.

Forever Encouraged

Under the terms of the 1794 Jay Treaty, Detroit, along with the Michigan lower peninsula, became part of the United States of America. As a territory, Detroit fell under the organizing principles of the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. Adopted under both the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union and the Constitution, the Northwest Ordinance provided that civil and religious liberty are “the basis of these republics,” and established an extensive list of positive rights, including protections for native Americans and a prohibition of slavery. The text of Northwest Ordinance on this point would later be the model for the 13th Amendment. The Northwest Ordinance also provided “Religion, morality, and knowledge, being necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, schools and the means of education shall forever be encouraged.” This quotation is inscribed over the facade of Angell Hall at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

Detroit was briefly lost in the War of 1812, when William Hull surrendered the city to a militia of British, Canadians, and native Americans led by a Shawnee Chief, Tecumseh. The surrender led to widespread violence as native American braves, encouraged by the British, attacked American settlements. Detroit returned to the United States when it was recaptured after the Battle of Lake Erie, also known as the Battle of Put-in-Bay at which Admiral Perry flew the battle flag “Don’t Give Up The Ship,” memorializing the dying words of his friend and fellow naval officer, Captain John Lawrence. That battle flag can be seen at the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, where it inspires midshipmen today.

In the antebellum period Detroit was an important stop on the Underground Railroad on the way to Canada. Notable Detroiters included Zachariah Chandler, a Whig abolitionist and financial supporter of the Underground Railroad. Chandler served as mayor of Detroit from 1851 to 1852. Chandler went on to become Secretary of the Interior during the Grant Administration, and then a United States Senator in 1879. Chandler is famous for taking the controversial stand, shared by Lincoln, rejecting the constitutional reasoning of the Dred Scott opinion, and for his “blood letter” warning:

But, sir, when traitorous States come here and say, unless you yield this or that established principle or right, we will dissolve the Union, I would answer in brief words, ‘no concessions, no compromise; aye, give us strife unto blood before yielding to the demands of traitorous insolence.’

Until replaced by a statue of Gerald Ford in 2011, Zachary Chandler’s was one of the two statues representing the State of Michigan in the Statuary Hall of the United States House of Representatives. Now the most tangible memory of Zachary Chandler is the 18-hole golf course at Chandler Park, Detroit. I played Chandler Park in my youth. Rumor had it then that the green at hole 6 and the tee box at hole 7 attracted muggers. I never met one there.

In 1860, as Lincoln ascended to the presidency, Detroit had a population of 45,000. During the Civil War, Detroit contributed staunch fighting men to the Union cause. President Lincoln is reported to have said “Thank God for Michigan!” when the First Michigan Infantry arrived to reinforce Washington, D.C. At Gettysburg the 24th Michigan Regiment, a unit of the Iron Brigade, suffered 73 percent casualties.

Detroit, like New York, was the site of a race riot in 1863. Race baiting articles printed in the Democratic paper (press in those days, even more than today, was affiliated with party), the Detroit Free Press, provided the tinder. The Detroit Provost Guard provided the spark, shooting a man in an attempt to disperse a lynch mob.

Wilbur Storey, who would later gain fame as an aggressive “copperhead” editor of the Chicago Tribune, had purchased the Detroit Free Press in 1853, planning for it to be “radically and thoroughly Democratic.” Copperheads were northern Democrats who were either pro-slavery, or indifferent to the institution and its spread. Copperheads constrained their support for the Union to preventing secession, and not at all costs. They were, generally speaking, what remained in the North of the Democratic Party after Lincoln exploded the doctrine of popular sovereignty in the Lincoln-Douglas debates. Detroit’s Republican paper, the Advertiser and Tribune, blamed the riot on the baiting of the Free Press and its Democratic readers, calling the riot “a Free Press mob.”

Politically, Detroit was dominated by Whigs until the election of William Duncan, Democrat, in 1862. Detroit would be largely dominated by the Democratic Party after the Civil War until 1890, when the city’s politics would realign to Republican.

During Reconstruction, Detroit thrived as a trading and manufacturing city. By the opening of the 20th century, Detroit had a population of nearly 300,000 and a metropolitan population of 650,000. Michigan had a long history of civil rights leadership, having prohibited segregation in education in 1867, in life insurance companies in 1869, and with regard to marriage in 1883. In 1885 racial discrimination was barred in public accommodations. In 1890, while it remained the federal rule, the Michigan Supreme Court rejected the “separate but equal” doctrine.

From this backstory is born modern Detroit. Detroit opens the 20th century as a place known for the conviviality of its people, a reservoir of taste descended from the French, a matching reservoir of industry descended from their British Protestant successors, and civil libertarian impulses.

Henry Ford’s Model

The greatest Detroiter of the early 20th century is indisputably Henry Ford. An industrialist who was active—sometimes directly—in politics, Ford played the founding role for modern Detroit. This industrialist celebrity had enormous influence over opinions of the great mass of Detroiters because he was the largest employer in a time of peace, when private interests were at their peak in defining what it meant to be an American and a Detroiter.

By the time Henry Ford began producing the Model T in 1908, Detroit had a population of 450,000 and a metropolitan population of 800,000. By the time the last Model T rolled off the Ford Motor Company’s line in 1928, Detroit had a population of 1,500,000 and a greater metropolitan population of 2,600,000.

Political leadership of the city was dominated by Republicans, most of whom were linked to Ford, directly or indirectly. Oscar Marx served as mayor from 1913-1918, was an affiliate of John Dodge, who was then an investor in Ford Motor Company. Marx was succeeded by his protégé, James Couzens, who was a co-investor in Ford Motor Company. Couzens was not bought out of Ford Motor Company until 1919. John C. Lodge, a Couzens protégé, succeeded Couzens as mayor after Couzens’ resignation in 1922. Lodge would serve as mayor three times, again after Joseph Martin’s resignation in 1924, and finally elected to the office in 1928. John W. Smith, a Warren G. Harding and Calvin Coolidge protégé, was mayor from 1924 to 1928.

Ford had many friends, among them Thomas Edison and President Coolidge. The three liked to call themselves “the vagabonds” and would go on camping trips using a Model T as an overland tractor. On one occasion it is said the vagabonds’ Model T broke down, and Ford crawled under it for repairs. The Model T was designed to be durable and easy to fix without complex tools. When Ford emerged from under the vehicle, a passerby came upon the three and asked who they were. Ford, smudged with grease, identified himself and said, “ . . . and this is Thomas Edison.” The passerby in disbelief interrupted him and said, pointing to the diminutive Calvin Coolidge, “And I bet you are going to tell me that this pipsqueak is the president of the United States.”

Coolidge devoted his presidency to restraining federal intrusion and shrank the federal government from the bloated war government of President Woodrow Wilson. Coolidge promoted a benevolent business environment, and a national rhetoric of the natural rights of the Declaration of Independence that recalled Lincoln and Jefferson.

In 1926 Coolidge would say in his Independence Day speech:

It is often asserted that the world has made a great deal of progress since 1776, that we have new thoughts and new experiences which have given us a great advance over the people of that day, and that we may therefore very well discard their conclusions for something more modern. But that reasoning cannot be applied to this great charter. If all men are created equal, that is final. If they are endowed with inalienable rights, that is final. If governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed, that is final. No advance, no progress can be made beyond these propositions. . . Those who wish to proceed in that direction cannot lay claim to progress. They are reactionary. Their ideas are not more modern, but more ancient, than those of the Revolutionary fathers.

In this political environment, Ford’s new industrial system drew black and white immigrants from the South and people from Eastern and Southern Europe. Once in Detroit they learned a new way of life, one in which unskilled labor could not just produce a surplus for a family, but also have the leisure and mobility to enjoy that surplus. They learned to be middle class.

After World War I, the mix of Eastern European, Southern European and American Southern blacks and whites brought not just foods and customs to Detroit, but also the Ku Klux Klan. Klan revival had begun under the Wilson Administration, following the release of a film sympathetic to the Reconstruction-era Klan, “The Birth of a Nation.” President Woodrow Wilson, a southern Democrat, had reportedly praised the movie after a screening at the White House, saying “it is all so terribly true.”

Such racial animosities were not unique to Detroit. The Klan had made formidable inroads in other places in the North, including Connecticut, New Jersey, Oregon, and Indiana. In the ’20s Detroit metropolitan Klan membership numbered around 40,000, in a metropolitan region of more than 2,500,000. Still, the Klan was entrenched enough to help elect a Klan-supported mayor, Charles Bowles, to office in 1930. He lasted only six months and then was recalled.

But to focus on Second Revival Klan infiltration of the North is not fair to Detroit. The Protestant Social Gospel movement also pitched its tent in Detroit. Reinhold Niebuhr, a German-American minister, preached vigorously against “Protestant bigotry the hardest” as a sin and implored that people were to be “judged by their fruits, not their roots.” Niebuhr, no genius, also criticized the assembly line as dehumanizing, missing altogether the benignity of the middle class it had created.

Detroit in the ’20s, while Protestant-dominated politically and economically, remained a very Catholic city. Detroit boasted the second-oldest Catholic parish in the United States, Ste. Anne de Detroit Catholic Church. Catholics within the Diocese of Detroit numbered about 350,000 in 1920 and 725,000 in 1929, meaning, depending on when you sampled, that somewhere between 70 percent and 40 percent of Detroiters were Catholics. Detroit then was then four to seven percent black, and 29 to 30 percent foreign born.

The Klan disappeared quickly from Detroit because it was never very welcome.

Detroit in 1910 to 1930 was multiethnic and religiously diverse. Detroit’s largest and most influential employer, Ford Motor Company, did not discriminate in hiring on ethnic, religious, racial or other grounds.

Ford did not think much of credentialed education. He would write in his biography that a prospective employee was “equally acceptable whether he has been in Sing Sing or at Harvard.” His factories were open to everyone equally and so were his wages: $5 for an eight-hour day (in adjusted terms today that’s $14 an hour, then an unthinkably large sum). Herbert Northrup, a Wharton School labor specialist, observed that at the Ford Motor Company in the ’20s and ’30s, blacks came “closer to job equality” than at any other large firm in the country. Ford Motor Company could list the first salaried black executive in America in 1923. James Price retired in 1947 to found a supplier to Ford Motor Company. Ford Motor Company also employed black labor in the much-feared Service Department—a “human resources” division—which enforced sobriety and good behavior among the workforce, with an eye towards productivity. A sober laborer in a well-ordered house performed better at work and at home. The Service Department also monitored, and frequently roughed up, union activists.

Ford was a new kind of industrialist, who believed that his innovations in assembly line production had made it possible for every man to earn a good living from a day’s work and that his product, an affordable automobile, had made the lives of common people better. In 1919 Ford Motor Company’s policy statement included this: “We have learned to appreciate men as men, and to forget . . . everything else outside of human qualities and energy.”

Ford’s welfare capitalism, as it was known, extended not only to ethnicity, religion, and race, but also to the physically disabled. Ford instructed his managers to determine how many jobs could be filled by disabled persons (4,034 out of 7,882) and to identify meticulously jobs that could be performed by legless, armless, and blind men. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Ford discovered that when you matched employees to the right jobs, the value of their labor—their productivity—rose and the differences in productivity among employees tended to flatten. Around this was built a flat wage structure and an obsession with time efficiency. Every task was judged by the time it took and the number and displacement of the motions needed to accomplish it, and refined until it was at the minimum of both.

Ford believed in business as “serving the people,” and made that case in Dodge v. Ford (Mich. 1919), where he argued publicly “My ambition is to employ still more men, to spread the benefits of this industrial system to the greatest possible number, to help them build up their lives and their homes. To do this we are putting the greatest share of our profits back in the business.” Ford lost that case. The Supreme Court of Michigan ruled that a corporation is run for the interest of its shareholders only, starting a line of cases that is just now being challenged with ESG.

Bury It in Debt

Ford’s enlightened industrialism took aim at unions. Ford believed unions exploited labor, and that union leaders, with their comfortable offices and privileges, burdened labor more than they helped. Ford’s high wages had started as profit sharing. And a union embattled with owners was fundamentally at odds with profit sharing and best practices. Hostility between labor and management eroded the efficiency which drove high wages.

Ford was suspicious of finance. After losing in Dodge v. Ford, Ford kicked the banks and financiers out of the company and changed his accounting system. No longer would a standard ledger of assets, liabilities, and shareholders’ equity, or statements of cash flows be used. Ford Motor Company would maintain a unique system of accounting based on minutes and seconds. Controlling the cost of labor in a product and increasing the value of labor meant reducing the amount of time needed for each task. This made Ford Motor Company highly efficient. It also meant Ford Motor Company often did not know how much cash it had on hand.

Ford’s suspicion of finance also led him to discourage the financing of his automobiles. Cash and carry or layaway were the only options. Ford did not want to lift the burdens of the new middle class he was creating only to bury it in debt.

I will mention it because it will come up: A Ford employee named Ernest Liebold ran the Dearborn Independent, which produced anti-Semitic articles. Ford denied direct responsibility for the content of the Dearborn Independent. Ford fell into disrepute for anti-Semitism, and after a lawsuit in 1927, he apologized publicly, disavowed anti-Semitism and ceased publishing the Dearborn Independent. Ford publicly apologized again in 1942 after a boycott of Ford products.

Alfred Sloan, who would lead General Motors, was an entirely different kind of industrialist. Sloan was educated at MIT. Ford neither had a college education nor believed higher education had much value. Sloan thought of General Motors in strictly rational financial terms. Ford thought of Ford Motor Company as an expression of ennobling work and efficiency whose benefits should be broadly shared. Sloan did not share Ford’s reasons—or methods—for resisting unions. After losing initial battles with the United Auto Workers, Sloan ceased to look for ways of knitting labor and capital together, and accepted a hostile labor-and-management relationship.

Sloan also pioneered a new kind of marketing which offered consumers choices, but not necessarily value. Sloan developed practices radically opposed to the design and marketing impetus behind Ford’s Model T. Styling changes—what Detroit automakers came to call “sizzle”—planned obsolescence, and price discrimination kept consumers on a buying binge, with each step in the process, from trade-in to the tapping of middle class aspiration to up-brand from Chevrolet to Cadillac, extracting a little more from the consumer. While Ford would build the Model T—a hyper-versatile and hyper-reliable car that came in one color—Sloan would promote the idea of “A car for every purse and purpose” the main purpose of which was to empty as much of your purse as possible.

Sloan recognized that GM could sell more cars, and make more money, if it financed the purchase. Thus was born General Motors Acceptance Corporation, or GMAC, in 1919. If Ford provided unskilled laborers with income, Sloan provided them with leverage. And it worked. GM would become the world’s largest and most profitable manufacturing enterprise. By the 1930s GM had eclipsed Ford. Things went swimmingly for GM until 2008, when legacy costs and a financial crisis forced it into bankruptcy.

Entrepreneurs and Innovators

By 1940 Detroit had a population of 1,600,000 and a metropolitan population of nearly 3,000,000. World War II brought demand for industrial production and, with it, demand for labor. General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler built planes, guns, and tanks. Henry Ford supervised the construction of the largest moving assembly line in the world at Willow Run to build B-24 Liberator bombers using the same techniques of mass production Ford had applied to automobiles. Detroit prospered enormously from the war.

When 1950 rolled around, Detroit had 1,850,000 inhabitants, and a greater metropolitan population of 3,700,000. Detroit had the highest per capita income and home ownership rate in the nation. If the expression had then been in circulation, Detroiters would have called the two car garage the “new normal.” Labor—unskilled and semi-skilled—had homes of brick, boats, and vacation homes near northern Michigan resorts. Detroit ranked nationally as America’s fifth largest city, just behind Philadelphia.

Through the ’50s the mayor’s office, nominally non-partisan, was in Republican hands: Albert Cobo (1950 to 1957) and Louis Miriani (1957 to 1962). Cobo added new modern construction to the downtown area of Detroit. Miriani expanded Detroit’s water system, freeways, and port infrastructure.

Detroit’s nine-member Common Council had two councilwomen. In 1950, Detroit elected Mary Beck, a Democrat, and in 1952, Detroit elected a second councilwoman, Blanche Parent Wise, a Republican and a Ford affiliate (she had sold trucks for Ford at a time when women did not sell trucks). Councilwoman Wise happens to have been my grandmother.

The structure of automobile manufacturing employed countless machine shops, which meant entrepreneurs and innovators thrived. Detroit had been the site of the first lined, cement road and the first automated four-way traffic light. Detroit was yet not a one-horse town. Fairchild was still producing aircraft in Detroit in ’52 and ’53 at the Willow Run Plant. SS Kresge, a Detroit five-and-dime retailer, was about to change its name to Kmart and further revolutionize consumerism, four months before the first Walmart opened. Among its many consumer innovations, Detroit invented the mall, opening the Northland Center in 1954. Detroit was a leader in entertainment. Berry Gordy, midwife to musicians such as Smokey Robinson, Diana Ross, Aretha Franklin and Michael Jackson, would found the Motown Record label in 1959.

Its boundaries enclosing 138 square miles, Detroit had room to grow. It boasted a Frederick Law Olmstead-designed park, Belle Isle, a soaring waterfront of office towers built in the boom of the 1920s, an extravagant theater district, an internationally recognized art museum, two universities within the city limits, proximity to the University of Michigan and the land grant college of Michigan State University, four law schools, two medical schools, and a leading hospital for vascular surgery. With the destruction of the Chicago Masonic Temple in 1939, Detroit could claim the world’s largest Masonic Temple, a very seen manifestation of an unseen influence on political and economic life for conspiracy theorists to ponder.

In the 1950s Detroit was outwardly living well, a very healthy city, technologically advanced, with economic diversity, prosperity, peace and civil life supporting the arts and sciences.

But all was not well.

Today Detroit has a population of just under 640,000. That’s 35 percent of its peak and 25 percent of its infrastructure design capacity of 2,500,000. By comparison, in 1940, Hamburg, Germany, where my mother was born, had a population of 1,750,000. Today Hamburg has a population of 1,850,000. And Hamburg was totaled in World War II by allied bombing.

Gone are the liberating mechanical consumer innovations of Detroit that had pointed to a future of the sort depicted in the television cartoon “The Jetsons.” In its place, we got something out of “Scooby-Doo.” Detroit ghosted America. What happened?

White Flight

Let’s start with political behaviors that anticipated today’s identity politics. In July of 1943, a massive race riot erupted in Detroit. Three days, 34 deaths, 1,800 arrests, and millions of dollars in property damage later, the riot ended. As the New York Times reported, “Federal troops in full battle regalia . . . moved into Detroit tonight to help city police, home guards and State troops restore order in the country’s worst race riots since East St. Louis (Ill) disturbances in the first World War.”

Between 1940 and 1943 approximately 350,000 migrants moved to Detroit in search of work. The bulk of these migrants were from the southern and rural regions of the country. The booming population in Detroit led to competition for homes and employment. The civil liberties protected by Michigan law and entrenched politicians surprised those who came from places where separate but equal (with the emphasis on separate) was the rule. Resentments festered.

Before the riots Henry Luce’s Life magazine would write in 1942:

If machines could win the war, Detroit would have nothing to worry about. But it takes people to run machines and too many of the people of Detroit are confused, embittered and distracted by factional groups that are fighting each other harder than they are willing to fight Hitler. Detroit can either blow up Hitler or it can blow up the U.S.

While Detroit had a combustible atmosphere, the chief organs of municipal government were sober and evenhanded. A housing shortage led to a new housing project located next to a white neighborhood. Many assumed it was a white project until it was given the name Sojourner Truth, after the abolitionist and women’s rights activist. Federal law segregated public housing (many New Deal programs were discriminatory), and Democrats in Congress intervened and re-designated the project as white housing. Detroit Mayor Edward Jeffries, a liberal Republican, reformer and Lodge protégé, who campaigned in 1940 as the mayor of all Detroiters, sensed a threat to his political coalition, and fought for black occupancy until Washington re-re-designated the housing project. In 1942, Mayor Jefferies backed this up with force, and 1,100 police officers and 1,600 national guardsmen were used to make the site safe for black tenants.

The 1943 riot altered the politics of Detroit. Detroiters attacked Mayor Jefferies for waffling over the Sojourner Truth incident, and Jefferies risked losing support of both black and white Detroiters. Believing he could not command the coalition which had first brought him to office, Jefferies changed his campaign approach. Jefferies blamed militant black leaders for the riots. This stance shut Jefferies out of Detroit’s proportionately small, but important black vote, and triggered the beginning of a political realignment.

In the 1950s, Detroit’s “white flight” began. Roots were shallow for many Detroiters. Fifteen percent of the city was foreign born and another 10 percent or more had migrated internally to Detroit during the war. Blockbusting—financing with a view towards destabilizing targeted tracts of housing—devastated the city. The pattern of rapid selling in integrating neighborhoods depressed property prices and created an economic feedback loop.

By the end of the 1950s the political dynamics in Detroit lurched leftward. In 1962, Jerome Cavanagh, a Democrat, was elected mayor, carrying a 69 percent majority and nearly all of the black vote, then a hair under 30 percent of the city. In the 54 years from 1908 until 1962 Democrats had served a total of 7.5 years in the Detroit mayor’s office. Since 1962, although the office is nominally non-partisan, all Detroit mayors have been Democrats.

Detroit from 1962 to 1967 had a large and prosperous black middle class, and higher than average wages for unskilled labor. The New York Times wrote Detroit “had more going for it than any other major city in the North.” Detroit had black representation on the city council, two black congressmen, three black judges, two black members of the Detroit Board of Education, and 12 black representatives in the Michigan Legislature. Detroit was considered a model for police relations by the Department of Justice. City government was in the vanguard of the civil rights movement. Cavanagh walked down Woodward Avenue in 1963 with Martin Luther King and 100,000 other Detroiters in the March for Freedom.

Cavanagh had national clout in the Democratic Party and had been elected to head both the United States Conference of Mayors and the National League of Cities. President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society meant massive federal intervention in urban politics, administration and economics, and Cavanagh’s prominence as a Democrat brought money—half a billion dollars in all—under the Model Cities Program (1966). Cavanagh, a darling of the Democratic Party, served on President Johnson’s task force for the Model Cities Program. With its five-year plans, the Model Cities mimicked the central planning of America’s communist rivals. One other thing: it failed. Spectacularly.

In July 1967 Detroit’s second major race riot of the 20th century broke out. Ultimately President Johnson invoked the Insurrection Act of 1907 and sent federal troops into the city. When the smoke cleared, 43 were dead and nearly 1,189 injured. More than 400 buildings were burned. 2,500 stores were looted. More than 7,000 people were arrested.

Cavanagh was shocked by the riots, believing he had done everything possible to improve conditions. Cavanagh had sought dialogue with radical groups, but never acknowledged that perhaps this had the effect of legitimizing radicalism not moderating it, folding it into the mainstream of civic discussion in Detroit.

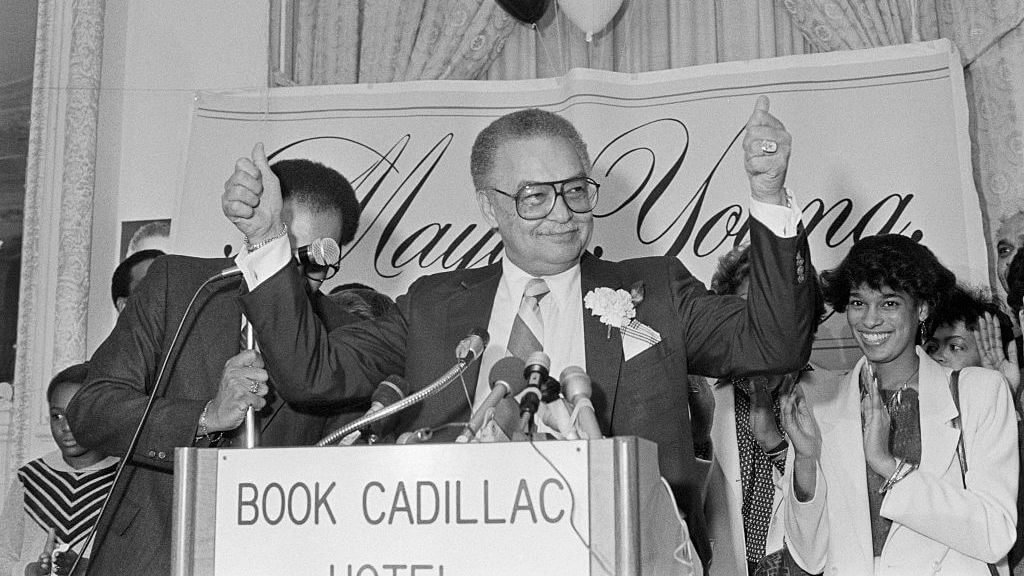

In 1970 a depleted Cavanagh was succeeded by Roman Gibbs, a Detroiter of Polish descent. In 1973, a former Tuskegee airman, Coleman Young was narrowly elected, on a vote that was split largely along race lines, with many white voters voting in favor of the former police commissioner, John Nichols, and blacks, constituting roughly 40 percent of the Detroit electorate, voting for Young. Young would serve for a record five terms, 20 years in all, until 1994 when he declined because of failing health to again.

Seems Stupid, and It Works

Young, I have to confess to the reader, is one of my favorite political figures, after Winston Churchill and Theodore Roosevelt. I grew up listening to Young, learning about him, and admiring his sense of showmanship and his no holds—and no words—barred rhetoric.

I judge him, however, by the corollary of a simple rule. The rule is: If it seems stupid, and it works, it isn’t stupid. The corollary is: If it seems smart, and it doesn’t work, it isn’t smart. It’s stupid.

Young started as a union activist for the UAW. In 1947, Young had been elected as the first black director of organization of the Wayne County CIO. Young’s political gifts, and his aggressiveness, quickly became well known. Young made a name for himself in 1952 when he sat in front of the House Committee on Un-American Activities. Young was loosely associated with a Marxist—a Detroit barbershop proprietor—named Haywood Maben, and HUAC was determined to get to the bottom of it.

Young, on the other hand, was determined, in his own words, not to “take any shit.” At the hearing, Young trained his sights on John Wood, a congressman from Georgia, who declared he hoped to avoid racial issues. Young would not accept that dodge. When asked “Are you now a member of the Communist Party?” Young cited the First and Fifth Amendments, and turned the tables. He denounced attacks on him as racist and turned to Wood to say “I happen to know, in Georgia Negro people are prevented from voting by virtue of terror, intimidation, and lynchings. It is my contention you would not be in Congress today if it were not for the legal restrictions on voting on the part of my people.”

When Young was asked if he would fight for his country against the Soviet Union, Young said, “I am part of the Negro people. I fought in the last war and I would unhesitatingly take up arms against anybody that attacks this country, in the same manner I am now in the process of fighting discrimination against my people. I am fighting against un-American activities such as lynchings and the denial of the vote. I am dedicated to that fight and I don’t think I have to apologize or explain it to anybody.”

Thus ended HUAC’s inquiry into Coleman Young. Young was now instantly recognizable in Detroit, and elsewhere.

As mayor, Young’s hot rhetoric had a tendency to be misunderstood. Young said: “I issue a warning to all those pushers, to all rip-off artists, to all muggers: It’s time to leave Detroit; hit Eight Mile Road . . . I don’t give a damn if they are black or white, or if they wear Superfly suits or blue uniforms with silver badges. Hit the road.” Despite the “I don’t give a damn” many white Detroiters believed Young meant them.

To explain his administration and its challenges, Young once said “Racism is like high blood pressure—the person who has it doesn’t know he has it until he drops over with a God damned stroke. There are no symptoms of racism. The victim of racism is in a much better position to tell you whether or not you’re a racist than you are.”

Young also used to like to say “You can’t look forward, and backward at the same time.” In fact, this sentiment is about looking backward, because as Young saw it there was little positive in Detroit’s past.

Young had experienced racism, and he did not see his story in terms of his upward path to the pinnacle of local politics—and then to the pinnacle of national recognition for local politicians—as a story of achievement and retreat of racial arrogance, but as one that had occurred despite it. Young saw his difficulties in governing as a rerun of the same stumbling blocks, and he fought against them with the same incendiary manner he used to cause a meltdown of Congressman Wood’s HUAC investigation.

Young liked vulgarity, and considered his foul mouth a point of pride. “Swearing is an art form,” he said. “You can express yourself much more exactly, much more succinctly, with properly used curse words.” The more entrenched Young was in power, the more relaxed he became with profanity in official discourse. Young once addressed Detroit reporters from Hawaii with “Aloha, Mother Fuckers.”

This racially tense political atmosphere and the erosion of civil discourse combined with crime. In 1965, two years before the ’67 riots, crime had begun to rise. By 1973 when Coleman Young was elected, the murder rate in Detroit was already above 50 per 100,000, an alarmingly high rate. Detroit’s murder rate ultimately climbed to 63.5 homicides per 100,000 in ’87, and during Young’s 20-year tenure never declined below 54 homicides per 100,000. Today there are only two large cities in the United States today with a murder rate above 50. When the experience of mass homicide spans a generation, habits change. Personal security becomes a paramount daily thought, and when security seems elusive, flight follows. By 1990 the population of Detroit was scarcely above 1,000,000 and plunging.

Detroit became not just a leader in murder, but a leader in property crime. In the 1980s alone there were some 500 to 800 acts of arson each year just in the three days before Halloween. Lest Halloween get all the attention, rampant celebratory gunfire on New Year’s Eve also became a custom. My first memory of New Year’s Eve is of a babysitter offering reassurance that the “pop-pop-pop” sounds coming from all directions outside my bedroom were fireworks. What’s yours?

Henry Ford felt history smothered innovation, and while he encouraged experimentation, he forbade the recording of experiments at Ford Motor Company. Ford felt that if something did not work, it should be tried again without knowledge of past failures, which might discourage a new and superior attempt. Perhaps this habit of thought, directed at innovation, found its way into the civic culture of Detroit and its poor regard for conservation of historical treasures.

Detroit had been known as the “Paris of the Midwest” for its architecture. To say that now to a stranger to Detroit is to elicit guffaws. Wealth and skilled labor erected many remarkable buildings, and a large number of these were permitted to fall into neglect or were demolished. Detroit is still famous—an internet sensation—for its apocalyptic architectural ruins. Pre-Young, Detroiters had disposed of Detroit’s Old City Hall, a landmark Renaissance Revival building constructed in 1868, because they thought the future would be brighter. Wrong. Young was indifferent to the loss of landmark buildings because to his mind the past was bad. Wrong again.

In any event, many Detroiters came to believe that Young focused on new development efforts at the expense of preservation, because preservation meant homage to a history of injustice.

Young was energetic in the construction of the Renaissance Center (conceived by Henry Ford II and funded privately by Ford Motor Company, and now, ironically, the General Motors headquarters), Joe Louis Arena, and the Detroit People Mover (funded by the federal Urban Mass Transportation Administration). But Young watched as institutions like the Detroit theater district fell to ruin.

Many Detroiters regard Young as beyond reproach. Many others regard Young as the cause of ruin. In his autobiography, Young blamed “white flight” for Detroit’s failures, and in turn considered “white flight” the result of fear remaining after the 1967 riots. The Young Administration, from Young’s point of view, was a victim of something it could not control. Yet Young’s chief means of politicking was to appeal to race; in curating a majority Young never failed to invoke race. When Young faced Ernest Brown in the 1977 election, Young taunted Brown, who was also black, with “boy scout” and “white hope.” In 1985, when Young ran for his fourth term against Thomas Barrow, again Young resorted to casting his black opposition as a “white hope.” In the end, Young left to his successors a racial majority so large (approximately 80 percent) that majority formation by race had ceased to make any rational sense. Talent of all races was streaming out of the city, and the downward momentum continued.

Young was succeeded as mayor by Dennis Archer (1993 to 2002), a successful attorney and Michigan Supreme Court Justice, and a good man. Archer was succeeded by Kwame Kilpatrick (2002 to 2008), the son of Carolyn “Cheeks” Kilpatrick, then the U.S. Representative for Michigan’s 13th congressional district, and a bad man. Kilpatrick, who assumed the title “Hip-Hop Mayor,” was convicted on March 11, 2013 of 24 federal felony counts related to the corruption of his office.

Kilpatrick was succeeded briefly by Kenneth Cockrel, Jr., who was succeeded by Dave Bing. Bing was succeeded by Emergency Manager Kevyn Orr, and Detroit was restructured under Chapter 9 of the Bankruptcy Code in 2013. The current mayor Mike Duggan succeeded Orr. Duggan is a reasonably competent mayor of a city now of fewer than 640,000, 27th in the nation, with a 33 percent poverty rate and a per capita income of $19,000, less than 1/3 of the national per capita income. Detroit’s French exit is complete.

Detroit’s French Exit

Yet Detroit’s French exit is still not fully explained. Politics is just part of the story. The other part is policy, particularly trade and globalization. Detroit’s middle class was created by a demand for unskilled labor. The specialization of labor in an assembly line, as discussed above, increased the productivity of the labor and its value. The shortage of labor, and in Ford’s case a kind of eleemosynary interest in the welfare of labor, forced the sharing of the economic rents of production with labor. The massive supply chain that serviced the industry created opportunities for entrepreneurship, in several tiers. And then the demand for labor for all the ancillary consumer and service industries demanded by the new middle class further supported wages. There was a lot to do that most people could do. And the everyman was well-paid.

From 1950 to today, United States manufacturing as a share of total employment fell from around 30 percent to less than 10 percent. Over the same period, United States manufacturing as a share of nominal GDP—the value of all manufacturing in the United States—fell from more than 25 percent to just above 10 percent.

From 1985 on, the share of national wealth held by 90 percent of American households tumbled 12 percent of the total, and the wealth held by the top 10 percent increased by that 12 percent. Over the same three decades, the share of household wealth owned by the top 0.1 percent of households grew from 7 percent to almost a quarter of all American wealth, 22 percent.

Some of this occurred as American economic hegemony after the Second World War declined. Much of the world’s manufacturing capacity had been destroyed in the war, and much of what had not been destroyed was behind the Iron Curtain. The United States economy was somewhat autarkic, meaning the economy was closed, independent, self-sufficient. As the world rebuilt its own manufacturing capacity, the productivity of their labor began to rise, while their physical capital was newer, and American manufacturing was subjected to new competitive pressures.

Detroit, however, was an innovative place and, as also noted above, had a diverse economy which included aircraft, entertainment, and consumer innovation. And the economy reacted by shifting to services and manufacturing which had higher margins, but which also required more skill. What was eroding was the specialization of the large integrated manufacturing which matched labor with the tasks it could perform best, as industry concentrated on the skilled tasks that had the highest return. The basis of Ford’s flat, high wage began to erode.

By 1950 average tariff rates had started to come down from their last peak during the Great Depression. For most of the nation’s history, protectionism had been a given part of trade policy. Trade protectionism had been the second most important cause of the American Civil War after slavery. High tariffs on imported manufacturing sheltered Northern industrial concerns and burdened Southern agricultural—cotton—export concerns. Following the Civil War, tariffs climbed again and then declined from 1910 to 1920 only to climb again in the Great Depression. Following 1950, free trade policies, backed by new macro and microeconomic thought emanating from places like the University of Chicago, pushed tariffs continually lower.

Everyone Else Was Making So Much Money

There’s a well-known joke. Two Chicago economists are walking down the street. One sees a $20 bill on the ground and says, “Hey, there’s a $20 bill on the ground.” The other says, “No there isn’t; if there were someone would have picked it up.”

If Detroit is an example of an economic principle, it is that the market does not always pick up money dropped on the ground. It takes the right policy to do that. The price of blind ideological pursuit of free trade was a loss of unskilled manufacturing jobs and a loss of the value of the labor of everyman. The only people who could pretend this wasn’t happening were those who had or acquired capital or who were acquiring skills—which meant they had the aptitude to acquire skills—and were benefiting from the higher rent of their labor driven by free trade.

“. . . [S]chools and the means of education shall forever be encouraged,” the noble phrase carved into Angell Hall, is limited to encouragement for a reason. The everyman is an everyman and not every man or woman has the desire and aptitude to gain skills, or to “learn to code.” Sometimes people just need a high-paying job that anyone can do.

If you think about it in terms of basic economics—about supply and demand—it becomes clear. If the market price of unskilled labor is, say, $25 an hour when the pool of unskilled labor is, to make up a number, 50 million people nationally, what happens when a material portion of unskilled jobs, by virtue of growing logistical infrastructure and changing trade regulation, can be performed by any number of people around the world? The available pool of workers expands dramatically and the market price or value of their labor goes down, hard. Imagine if just 20 percent of the unskilled labor that was outsourced to China had remained in the United States because United States trade policy had constrained its departure? Detroit might be a very different story.

Further, within a firm what happens to the incentives of the employer? To increase profitability when labor is in limited supply, the employer must find a way to increase the productivity of that labor. To increase profitability when labor can be accessed nearby or abroad, an employer can seek to increase the productivity of the labor he has nearby, or he can seek to find similar and less expensive unskilled labor somewhere else in the world and have the product shipped back on a containership (likely built in South Korea).

President Ronald Reagan campaigned in 1979 on the idea of a North American free trade zone. It’s a spot of irony that Detroit hosted the Republican convention in 1980. “Go, Ronnie! Go!” the delegates cheered from the floor of Joe Louis Arena.

By 1988 the United States had signed an agreement with Canada and by 1993 the United States had signed a similar agreement with Mexico. While Canada’s labor was expensive, it was indirectly subsidized by the Canadian national system of healthcare. In the United States, since each employer paid for the healthcare of its full-time employees, there was no subsidy. As a result, competition with Canadian labor depressed the value of American unskilled labor. When Mexico came online into NAFTA, a large number of manufacturing jobs rapidly made their way across the border to maquiladoras, duty-free manufacturing facilities.

These free trade opportunities, and growing ones around the world in Asia, especially China, vastly increased the value of American financial capital as well as managerial and services human capital, which now had access to almost unlimited amounts of unskilled labor. United States GDP soared, but the benefits of this growth flowed to skilled labor and financial capital.

At the risk of repeating myself, not everyone participates in the shift from unskilled labor to higher skilled, higher margin labor. Detroit was hit very hard by this, and very few people like to talk about it. And the reason for the silence is everyone else was making so much money on the new economy that they had no incentive other than to cheer what was paying them and blame those it harmed for their growing poverty.

No Stranger to Bankruptcy

The automakers, which were essential to the high wage employment of unskilled labor in Detroit, started to develop a problem. As their workforces shrunk, as labor was outsourced around the world, the legacy retirement and healthcare costs of their former employees became a greater and greater portion of their total cost of labor. That is, as labor retired, certain pension and healthcare benefits that had been bargained for in union contract negotiations continued, even as the workforce shrank. Automakers became top-heavy with OPEB (other postemployment benefits) costs. And while the national economy was doing well, manufacturing, particularly automakers, became increasingly insolvent.

Detroit is no stranger to bankruptcy. It is ironic that Detroit helped make bankruptcy a respectable business. Detroit automakers outsourced the manufacture of nearly all components of their vehicles and focused on the higher return business of design and assembly.

A huge supply chain of Tier I, Tier II and Tier III suppliers came into being which provides parts to the automakers (the tiers designate whether the supplier furnishes directly to the automaker or to another supplier in the chain). A vehicle cannot be completed if it is missing any one part, and an entire assembly line can be interrupted if a single supplier fails. An interruption of supply, even briefly, has the potential to cost automakers tens of millions of dollars, or more.

Automotive suppliers are captive businesses in a “monopsony” or “oligopsony” arrangement, meaning typically they depend on one or two large customers who control demand and thus, within limits, pricing. Automakers pressured by OPEB costs and competition sought to manage for cash and capital by leaning on the capital of their suppliers by pressuring pricing, which they controlled. As thin-margined suppliers faltered—because of the oligopsony purchasing arrangements this is often not an unforeseen event—Detroit automakers needed ways to keep their distressed suppliers operating. The flexible provisions of Chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code, designed for rehabilitation, work well in this context.

Suppliers are not liquidated but reorganized, or at least kept operating until supply can be re-sourced. With many suppliers in a process of restructuring, the automakers have departments of bankruptcy specialists to manage relationships with insolvent suppliers. Financial advisors expert in bankruptcy multiplied in Detroit. Firms like Plante Moran, Alix Partners, BBK (now part of KPMG), and Conway McKenzie (now part of Riveron), that are located or were seeded in Detroit, are internationally recognized turnaround specialists. A multibillion-dollar industry of restructuring professionals grew out of the Detroit automotive supply chains. A late 20th century, and an early 20th century Detroit innovation was bankruptcy as a money maker, around which teemed a large number of highly compensated and highly skilled lawyers, accountants, and other professionals.

There were also changes in consumerism. Ford had designed the Model T around the common man. He made it simple, reliable, cheap, and easy to service. Sloan brought designed obsolescence and an addictive need for new styling. Sloan invented these things. But he was the beginning, not the end.

As global trade reduced the cost of labor, and product margin fell, the need for volume of sales grew in importance. Great efforts were put into making products that were cheap—because the middle class which was to buy them was suffering an eroding purchasing power—but also products that were high volume. Cheap global labor trends toward high obsolescence, the zenith of which is disposability.

As the tech industry grew on the West Coast and the financial industry grew on the East Coast, did Detroit benefit? The new tech industry devoted itself to internet consumer technology which scaled easily but was also dopamine driven. Shopaholism and social media addiction schemes are a far cry from the beneficial change of mobility and high wages of mid-century Detroit. The profits went to very few, the adverse effects fell on many.

Where the American middle class once sought high quality durable goods that were built to last, the new economy favored low durability, high obsolescence, and disposability. That is, the new economy favored that for most people. Tracking the new income inequality, the United States luxury goods market consisting of clothes and cosmetics soared to over $70 billion in 2022. And in the high-end durables a similar trend occurred. Sub-Zero and Wolf for me. Made in China for thee. Your grandmother’s middle class marketed Maytag that lasted for a generation, to the despair of the Maytag repairman, doesn’t exist today.

These changes intersected with the encouragement of consumer credit. The more the consumer can finance, the more that he can buy, and the more money that can be made on the financing. From the 1960s on consumer credit went from simple and regulated, and confined to the upper middle class, to widespread and broadly available. Consumer credit went from being a privilege to a necessity to a civil right with the Equal Credit Opportunity Act of 1974. This is not to criticize the fairness issue but to point out the growth of the practice and its misguided embrace as an unambiguous good.

As the value of unskilled labor declined in real terms as global trade crushed its purpose domestically, what little it had left was buried in credit, which was extolled as a good. Suddenly Antonio’s misfortune in the Merchant of Venice became a right to be celebrated.

Consumer credit from 1950 to 2020 grew as a percentage of GDP from 7 percent to 20 percent. By 2005, consumer credit had swelled to around 17 percent of GDP, big enough that Congress passed the Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act, which made it harder for overstretched middle class borrowers to file for bankruptcy and address their debts. BAPCPA, named by someone from the department of unpronounceable acronyms—perhaps they thought against the middle class having a memorable name for what had been done to them; when Congress wants the middle class to remember the department of acronyms comes up with something like PATRIOT—forced debtors into Chapter 13, squeezing them for the last few nickels.

Subprime lending came to Detroit in the aughts and then collapsed. Home prices in Detroit dropped to previously unimaginable levels. By 2007, Detroit had the highest foreclosure rate in the country. Since the 2008 financial crisis, many homes in Detroit have sold for far below construction cost—some for almost nothing at all—and the best stock was snapped up by fix and flip financial interests to be converted to rental. The rest was largely abandoned.

And all that and everything said before is why Detroit left the room, quietly and unseen, such that most Americans know nothing of its former wealth and the middle-class life it invented.

Preferring not to end on a downbeat, I ask, who among us, though, hasn’t on some unfortunate occasion overdone it and made the French exit? We came back and remembered to do better the next time.

Speramus meliora; resurget cineribus.