You may remember your civics class showing a diagram of the three coequal branches of government and explaining what each one does: The legislative branch passes laws, the executive branch is responsible for implementing those laws, and the judicial branch adjudicates legal disputes.

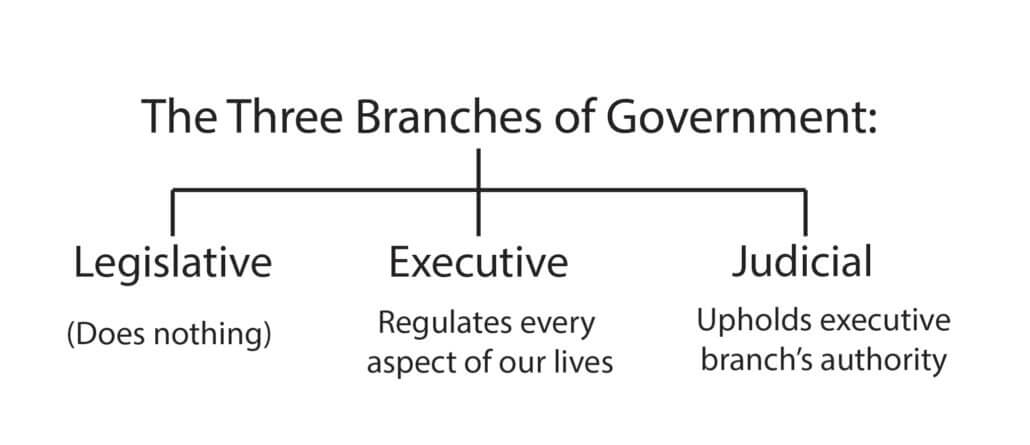

Since that is no longer the way our government works, I have done my own diagram illustrating the federal government in 2022:

You’ll notice that we still have three branches of government, but their purpose has changed dramatically. The legislative branch, which formerly passed laws, now has no responsibilities whatsoever. Their members simply sit around for 30 or 40 years, holding press conferences and collecting money.

You’ll notice that we still have three branches of government, but their purpose has changed dramatically. The legislative branch, which formerly passed laws, now has no responsibilities whatsoever. Their members simply sit around for 30 or 40 years, holding press conferences and collecting money.

The executive branch, which was supposed to implement laws the legislature passed, now does all the legislating itself in the form of regulation. This branch contains everything from the EPA and the FBI to the ATF and the IRS, and dictates everything from the forms you’re required to fill out to what you are allowed to do on your own “property.”

The judicial branch was supposed to be the umpire in legal disputes. America’s highest court, the Supreme Court, was a place of final appeal whose powers were not delineated differently from any of the lower courts. The power of “judicial review”—the right to decide which laws are constitutional—is not granted explicitly to the Supreme Court by the Constitution.

Perhaps the question of constitutionality was deliberately left hazy: Some lesser founding fathers, and the Supreme Court itself, took the position that it was the Court’s prerogative to decide whether a law was constitutional. John Marshall’s argument on the subject, essentially, was if we don’t have the power, then who should? “To what quarter will you look for protection from an infringement on the Constitution, if you will not give the power to the judiciary?” he said at Virginia’s ratifying convention in 1788. “There is no other body that can afford such a protection.”

Greater men—Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in particular—had a ready answer: You give that power to the states, obviously. Each state has a right to nullify unconstitutional laws, and in fact has a positive duty to interpose itself between its own citizens and a grasping federal government.

In John Marshall’s view of the Supreme Court—just as you’d expect—the justices would be wise and trustworthy beyond ordinary men. But Jefferson and Madison knew that the government would be doing unusually well if its officials managed to be no worse than ordinary men, and that only a fool or an aspiring tyrant would expect them to be better.

With Jefferson and Madison’s philosophical backing, the principle of nullification was asserted regularly by states—and just as regularly ruled out of order by the judiciary. But both sides, the states and the judiciary, implicitly understood that the right of constitutional review was hanging in the balance, and that it behooved them to be sober and cautious when asserting their claims.

The Civil War destroyed state power permanently, and nullification went with it. That left the Supreme Court in sole possession of judicial review. The federal government would now be responsible for restraining itself: it would review its own actions, sit in judgment of itself, and decide whether it was behaving well. This could only end badly, and, inevitably, it has.

In 1938, the Supreme Court was striking down Franklin Roosevelt’s unconstitutional expansion of federal government right and left. Everyone remembers that FDR tried—unsuccessfully—to expand the Supreme Court to overcome this problem. And the history texts teach us that, since the court was not expanded, it was a triumph of “checks and balances.”

Hardly. FDR didn’t pack the court because he didn’t need to: The justices who had blocked his policy initiatives very obligingly died. By 1940, FDR had appointed five justices on the court, remaking it entirely in his image. By 1943, he had appointed eight of the nine justices. The decisions began to roll in the other direction.

Wickard v. Filburn (1942) was the crux of the fight between the federal government and individual citizens. And, thanks to the new Supreme Court, we lost.

Roscoe Filburn was an Ohio farmer, growing wheat to feed his own cows. Roosevelt claimed the right to decide what crops every farmer could grow, and how much he could grow, based on the right of the government to regulate interstate commerce. Filburn said that because he wasn’t selling his wheat he wasn’t engaging in commerce—and he definitely wasn’t engaging in interstate commerce, so the government should just butt out.

In 1938, the Supreme Court would have taken Filburn’s side. But in 1942, the new court agreed with FDR: Filburn was engaging in interstate commerce, they said, because if he grows his own wheat, he changes the complexion of the interstate wheat markets by not buying someone else’s wheat. So it was interstate commerce after all.

But wait a minute: If a farmer growing wheat to feed his own animals actually counts as engaging in interstate commerce, then what isn’t interstate commerce? The answer: Nothing.

That opened the floodgates and led both to the destruction of legislation as a means of making laws and to the death of any limits on federal authority. Federal law enforcement? That exists to regulate interstate commerce. The ATF? That’s interstate commerce! The EPA? That’s interstate commerce, too. The right of these agencies to do what they do—and even their very right to exist—is upheld by the Supreme Court’s view that absolutely everything is interstate commerce.

And so what the Supreme Court has told us, since 1942, is that when the Constitution says that all powers not explicitly granted to the federal government are reserved to the states and the people, it means nothing at all. And that when the Constitution says the federal government may regulate interstate commerce, it actually means everything under the sun.

Voilà! Your independent judicial branch!

And so it really doesn’t matter if the Supreme Court recently has made a “good” decision or two. Just because it now claims that there isn’t a right to abortion in the Constitution, for example, shouldn’t let you forget that this goes hand in hand with saying, “Whoops, we misunderstood the Constitution 50 years ago and millions of children were aborted as a result—our bad.” If anything, this points to how utterly inept the Supreme Court is. They are susceptible to political influence, and occasionally they just get things completely wrong. In other words, they are no better than ordinary men.

The solution is for states to reassert their dormant rights—not in a single, union-shattering move (which is what the federal government is hoping for, so they can really tighten the screws). But little by little, over time, the states must rediscover their duty to interpose themselves between Americans and a power-hungry, corrupt, fat and greedy runaway government.

Some states have taken tentative steps in this direction. In 2009, the “Montana Firearms Freedom Act” asserted that weapons manufactured in Montana and not sold outside the state were not subject to ATF regulation. But Montana then submitted the law to the judgment of the federal courts, where, not surprisingly, it was invalidated.

Any state actually willing to cut the interstate commerce clause down to size would not have to stand alone: It would have the enthusiastic support of its citizens, including many new residents. And it wouldn’t be long before that state was joined by others, all demanding nothing beyond those basic rights which are guaranteed in the Constitution but ignored by the courts.

Remember the real system of checks and balances: It isn’t between different parts of the federal government; it’s between federal government and state governments. That was supposed to be our guarantee of limited government. Without that counterbalance, there’s nothing to stop the federal government from running away with the whole show. It’s time for the states to do their part.