There are plenty of ways to ration water, and California’s state legislature is pursuing all of them. Restrict agricultural water allocations until millions of acres of California’s irrigated farmland are taken out of production. Ban outdoor watering entirely in urban areas. Monitor residential indoor water use and lower it to 40 gallons per day per resident, with heavy fines to urban water agencies that cannot enforce those restrictions. But this is a lose-lose proposition, wreaking economic havoc and diminishing the quality of life for all Californians.

The initiative we authored and attempted to qualify for the November 2022 ballot acknowledged the importance of conservation, but focused on supply. Passage of this initiative would have eliminated water scarcity in California. Looking to the next two-year election cycle, the latest possible filing date for a new attempt to place an initiative on the November 2024 ballot is September 2023. A smarter approach would be to file an initiative around March 2023 in order to be gathering signatures from late spring through early fall in 2023. That would avoid competition with other political campaigns that promise to overwhelm 2024, and it would allow signature-gatherers to approach voters who are likely to be enduring a second consecutive summer with the most severe restrictions on water use they have ever experienced.

The sad reality, however, is these plans are worthless without access either to millions of dollars in donations, or a volunteer movement with unprecedented scale and unity. But building a grassroots movement to demand more water supply infrastructure can easily be disrupted by opponents.

This was evident in the press coverage of our campaign, where we were tagged both as extreme Republicans as well as puppets of Big Agriculture. The smear campaigns worked, as we may have expected. In California, even moderate Republicans—which are a minority of the GOP grassroots but attract the majority of the donations—will not get involved with anything they think is associated with either the Newsom recall effort or the so-called MAGA movement. Independent voters and Democrats, even if a cause is explicitly bipartisan—as ours was—will not associate with “extremists.” The impact of these schisms is to kill larger grassroots movements before they’re even born. You can’t unify an electorate in California, or a donor community, if more than 6 million of your potential allies are branded as too toxic.

It certainly doesn’t end there. As we have seen, the farmers were divided among themselves. And potential supporters, everywhere, would often vehemently object to one aspect of our plan, and on that basis withdraw their support even though they approved of the rest of it. The most controversial elements of our initiative were to include reservoirs and desalination as eligible projects and to include provisions that would have streamlined environmental regulations. In each of these controversial cases, we believed they were too important to leave out. But our opponents portrayed those elements of our initiative as extreme threats to the environment. This was unfair and it was inaccurate, but as always, it was very effective. Nobody wants to destroy Mother Earth!

Not only were we tainted as right-wing extremists bent on destroying the planet, we were accused of being puppets of “Big Ag.” This was a smart divide-and-conquer tactic because it helped cement the perception in the minds of urban voters that farmers are the problem, that farmers are taking all the water. And just as there is some merit to the environmentalist position that our current mode of middle-class living is unsustainable, you can make the case that Big Ag has gotten more than its fair share of subsidized water. To review a vivid portrayal of the Big Ag players in the western San Joaquin Valley that is so cynical it’s entertaining, read the series “A Journey Through Oligarch Valley,” a 31-page screed written by Yasha Levine in 2013.

Oligarchs Have a Vested Interest in Water Scarcity

You can disagree with Levine without dismissing his entire argument. Where he missed the point by a mile, however, is that oligarchs—all of them, not just the “Big Ag” variety—have a vested interest in less water, not more water. To the extent that some of the alleged villains in Levine’s book considered supporting our initiative, they were doing it for altruistic reasons more than for their own self interest. Our initiative, had it been approved by voters, and based on how it was written, would have likely resulted in tens of billions of dollars from the state’s general fund going to Los Angeles and other major coastal cities to pay, for example, to reuse 100 percent of urban wastewater, to restore portions of the Los Angeles River with natural habitat and spreading basins to recharge aquifers during storms, and replace the toxic pipes in Los Angeles public schools.

Steve Greenhut, in his 2020 book Winning the Water Wars, has this to say about the financialization of water and land:

The state needs to reform its regulatory barriers to water trading, so water-rights holders are better able to sell water to those who need it most. California also needs a better pricing system to allow markets to work their magic. But pricing must come against a backdrop of water abundance rather than one that leaves everyone fighting over an artificially capped supply.

When water pricing comes “against a backdrop of water abundance,” one thing is certain. The price of water will drop. The primary beneficiaries of lower prices will not be the so-called oligarchs of Big Ag and the hedge funds that are gobbling up farmland for the water rights. In many cases lower prices for water will impede their efforts to buy out smaller farmers and will undermine speculative investments in farm properties. The beneficiaries of lower prices will be farmers who produce vital row crops that are only economically viable when water is affordable, ensuring California continues to produce diverse agricultural products in-state. The beneficiaries of lower water prices will be urban water agencies and their ratepayers, including businesses that rely on affordable water. And the only way to accomplish this is for the state to pay for massive investments in water infrastructure, just like it did back in the middle of the last century.

To pay for more water, the price tag we’re looking at today is actually more affordable than it was back then. The 1957 California Water Plan had a total estimated construction cost of $11.8 billion. The state budget in 1957 was $1.9 billion, with a capital outlay of $440 million—23 percent of the entire budget. Through a combination of bonds and general fund allocations, the California State Legislature in 1957 resolved to spend an amount equal to six times their annual budget to build water infrastructure.

These comparisons are stunning because they illustrate just how big these legislators back then were willing to think. In 2022 dollars, $11.8 billion is worth over $120 billion. For water infrastructure, that’s a huge number, dwarfing the amounts that have been suggested in even the most ambitious recent proposals. Yet it is only equal to 42 percent of today’s $286 billion state budget. While California’s legislature is spending money today on things they couldn’t imagine back in 1957, that doesn’t mean California’s policymakers can’t commit to spending one hundred billion dollars, or more, on water infrastructure today. Sixty-five years ago, as a percentage of that year’s state budget, California’s legislators committed more than 12 times as much.

A 21st-Century Water Plan to Match the 20th-Century Plan

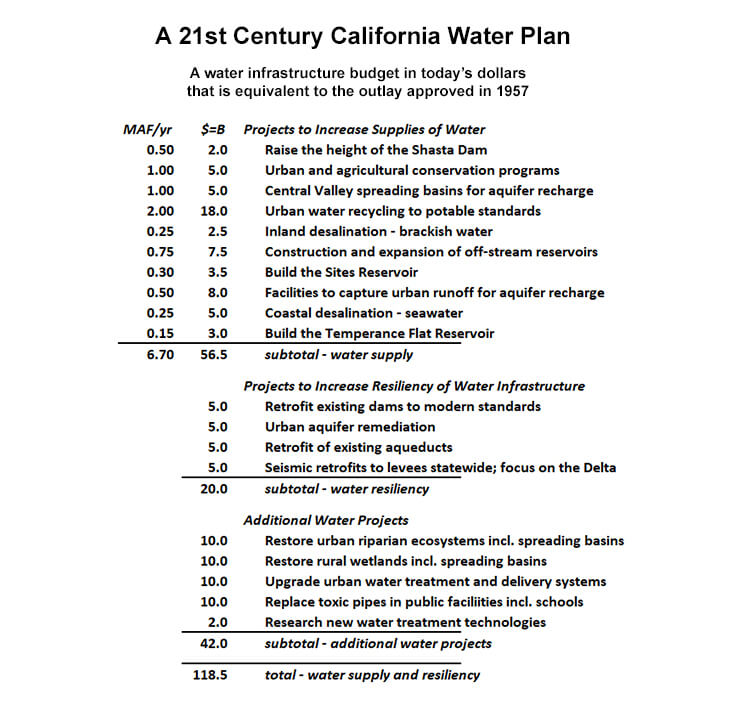

Imagine what Californians could do with $120 billion dollars to spend on water infrastructure, keeping in mind this hypothetical budget is only using state funds and doesn’t account for local or regional government matching or private investments:

Every one of these budget items would qualify as an eligible project under our initiative as it was written, with the only limitation being that funding would cease when 5 million acre-feet of water per year were being produced by new projects. The order in which the projects to increase the supply of water appear on this chart is not random. Notwithstanding the fact that getting reliable and consistent cost projections per project category is difficult because projects in the same category can often have very different costs based on very different circumstances, these projects are listed in the order of cost-effectiveness. And at the top of this list, fairly unambiguously ranked as the most cost-effective way to get more water, is to raise the height of the Shasta Dam.

To delve too far into the politics or the costs of these various projects and project categories is not the point of this report. Yes, the Shasta Dam is a federal project, but it belongs in any discussion of how to increase California’s water supply. And some of the urban wastewater recycling quotes I saw, from authoritative sources representing water agencies in Northern California, showed a projected ultimate per unit cost that exceeded current projections for the proposed Huntington Beach desalination plant. That certainly doesn’t mean we eliminate wastewater recycling as an option.

The point of this report is the amount of money it would take to create permanent water abundance in California in this century is an amount that the planners back in 1957 would have considered trivial. What is $120 billion in current dollars, only 42 percent of the state budget, in 1957 dollars was six times the state budget at that time. The argument that one typically hears from conservatives—government spending is wasteful—may be true but could not be less relevant in this case. And the argument often heard from liberal economists, that even wasteful government spending creates a positive ripple effect because all that wasted money gets spent over and over again in the economy, could not be more true in this case.

The Case for Government Subsidizing

Construction of Water Infrastructure

The reason the government subsidizes water projects is that affordable and abundant water lowers the overall cost of living and doing business. It lowers the cost of food. It lowers the cost of housing. It lowers utility bills. This is an economic ripple effect that has no rival. Government funds spent on high-speed rail create good union jobs, and the increased spending by those workers stimulates the economy. But that’s as far as it goes. High-speed rail, if it’s ever built in California, will be a permanent drain on the economy. There are better, faster, cheaper solutions to transportation challenges. But affordable and abundant water is a core enabler of economic prosperity.

Conservatives should see the appeal in the case for subsidizing water infrastructure because without the subsidies on the front end, to build huge capital projects that smash the price equilibrium for water and make it affordable, there will be a greater need for subsidies on the back end. Billions will instead have to be spent on an enforcement bureaucracy to ration scarce water, along with the enforcement hardware—such as dual residential meters to monitor indoor versus outdoor use—and additional billions will have to be perpetually spent to subsidize low-income families who cannot afford their water bills, food, and housing.

Investing in abundance at the level of basic economic essentials—water, energy, and transportation infrastructure—is the role of government. Without debating whether or not other spending priorities are an appropriate role for California’s state government, they should not have arisen at the expense of infrastructure spending. Not only has the state legislature effectively created a zero-sum game, where new spending priorities supposedly preclude massive spending on infrastructure, but what infrastructure spending survives is mired in bureaucracy and litigation.

It would be a productive compromise to accept the reality of bureaucracy and litigation doubling or tripling the cost of infrastructure if the most worthwhile projects were ultimately built. After all, that wasteful excess spending would trickle through the economy as bureaucrats and litigators spent their paychecks. Accepting this compromise seems to be the consensus among most infrastructure advocates at water agencies around the state. Let’s wait 30 years to get permits, let’s give the environmentalists everything they ask for, and let’s settle for pennies on the dollar in terms of actual usable water because that’s better than nothing.

The problem with this reasoning is it accepts the legitimacy of scarcity. It accepts the premise that a middle-class lifestyle is unsustainable. It rejects the possibility that technological innovation will solve the challenge of producing abundant and affordable energy, and ignores the fact that producing another 5 million acre-feet of water per year in California would only require a minute fraction of the additional generating power the state legislature is going to need to achieve their goal of an electric age.

Choosing abundance by investing in providing the basics of life, starting with water, is the only way California can set an example to the rest of the world. It is also the only choice that accurately reflects California’s legacy and culture. It is a choice that embraces the power of adaptation and chooses optimism over pessimism. It is also a realistic choice, because choosing abundance by adopting an all-of-the-above approach to producing water is the only path consistent with how every aspiring nation on Earth intends to serve its citizens. California’s designs, for dams and desalination plants, wastewater treatment plants, and facilities for stormwater capture, can be the cleanest, best solutions in the world.

The initiative we developed, perhaps more than anything else, was an attempt to inspire Californians to think big. Across so many of California’s industries throughout its history that has been an intrinsic theme. Today California’s high-tech industry is changing the world. California’s music and entertainment industries remain one of the defining cultural influencers on earth. California is a land of big mountains and big trees, a big valley, a perfect climate, and one of the most beautiful coastlines anywhere. California is a land of dreamers who made their dreams come true. California’s first water plans exemplified the best of that century’s ideas and potential and created a marvel that remains unrivaled. Using everything we’ve learned, it is time to do the same in California for this century. It is time to make the abundance choice.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared on the website of the California Globe.