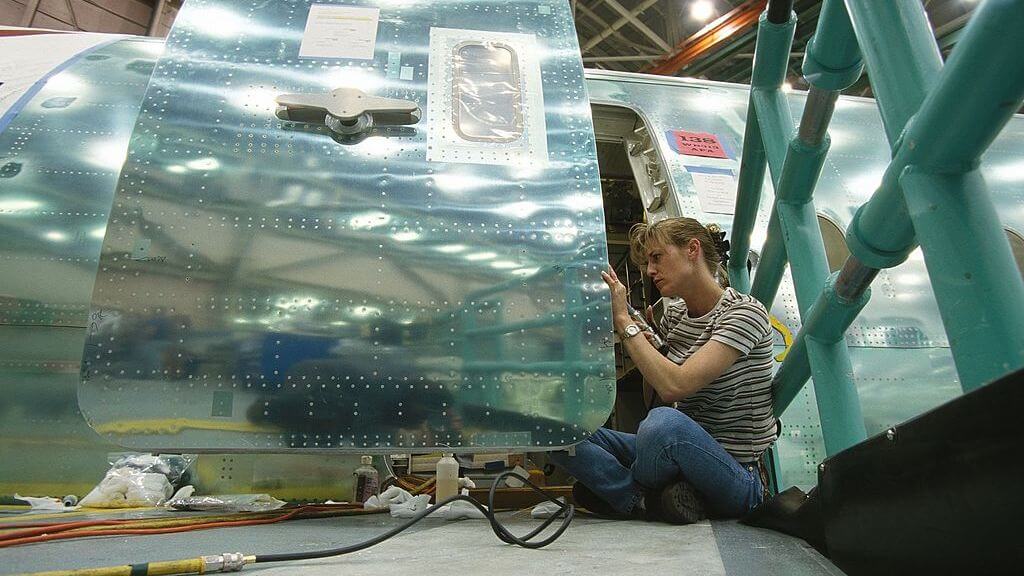

The Government Accountability Office on Wednesday revealed that Boeing is having trouble finding qualified workers for its nearly $5 billion Air Force One project. Thanks to COVID-related delays and retirements, the project is understaffed and behind schedule. The aviation giant has already lost $1.1 billion on the deal, which was contracted in 2018 at a fixed price of $3.9 billion and may not be finished until mid-2025.

Not just any warmblood with a wrench can walk in and get a job assembling the president’s jet. Due to the top-secret nature of the aircraft—actually, two specially converted 747-8s that the Air Force officially designates as the VC-25B—anyone working on the project needs to undergo an in-depth background check for a security clearance.

“Employees must meet stringent security requirements to work on the VC-25B program because of its presidential mission,” the GAO explains in its annual report to Congress on the Pentagon’s sundry weapon systems. “VC-25B officials said that Boeing continues to work with the program office to improve the prescreening process for applicants to ensure timely processing of security clearances.”

Because the job concerns the president’s life and safety, would-be workers get extra scrutiny. Have they ever been arrested or smoked pot or traveled extensively abroad? They’d better not lie because federal investigators will ask their friends and their enemies.

Those special circumstances aside, Boeing’s workforce challenges speak to a much greater problem. Fact is, aviation workers are not merely warmbloods with wrenches. They are highly skilled workers in a highly specialized industry. People with the sort of skills Boeing needs are a rare commodity who often command higher-than-average wages.

The problem, then, is a skilled-worker deficit.

Plenty of Work, Not Enough Workers

For years now—at least since the Great Recession—America has had far more job openings than it has qualified workers to fill the jobs. And the pandemic sure didn’t help. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reports 11.4 million jobs were available at the end of April, down 455,000 over the previous month. But at the same time, businesses hired only 6.6 million workers, similar to the month before.

While the real unemployment rate stands at a relatively low 7.1 percent, the labor participation rate is about as bad as it’s ever been, hovering around 62.3 percent. Millions of Americans who could work don’t work. That has left certain industries such as construction, manufacturing, and pharmaceuticals struggling to hire qualified talent. Almost all of those jobs require particular skills, but many of them can be learned without the need for a college diploma.

Yet cultural, social, and political trends over the past three decades or so have emphasized a four-year university education at the expense of the skilled trades, which a person could learn at a community college or vocational school in just a year or two. Though people like Mike Rowe have fought valiantly against the perception that “dirty jobs” are somehow bad jobs, at some point, Americans decided physical labor was disreputable and demeaning. “Do your homework and stay in school,” the message went, “or you’ll end up digging ditches for a living!” Put somewhat differently, why be a sweaty plumber or an electrician when you could pursue a glamorous career in business or advertising or the visual arts? (Why indeed.)

As countless data entry “specialists,” cashiers, customer service reps, and baristas across the country have since discovered, a degree in business or finance or—God help us—philosophy or political science is no guarantee of a corner office and a middle- or upper-middle-class lifestyle. Nevertheless, nearly 60 percent of all jobs in the United States today require a college degree.

It’s stupid. We’re putting resources and placing emphasis in the wrong places. Economist Richard Vedder argued more than a decade ago—that is, before the nation’s mounting student-loan debt crisis became a high-profile political cause célèbre—that the United States “overinvests” in higher education.

“Some 17,000,000 Americans with college degrees are doing jobs that the BLS says require less than the skill levels associated with a bachelor’s degree,” Vedder wrote in a 2010 essay for the Chronicle of Higher Education.

“Over 317,000 waiters and waitresses have college degrees (over 8,000 of them have doctoral or professional degrees), along with over 80,000 bartenders, and over 18,000 parking lot attendants,” he noted with clear bemusement. (Emphasis in the original.)

Surely, we don’t need bartenders with Ph.Ds. But we most certainly do need good plumbers, pipefitters, electricians, steelworkers, welders, fabricators, and machinists even—especially—as automation and artificial intelligence assume larger roles in our economy. As sophisticated as our technology is becoming, somebody needs to know how to fix those robots. As “perfect” as artificial intelligence may be one day, algorithms—written by human beings after all—cannot do everything. There can be no substitute for human judgment, flawed as it always will be.

Held Hostage By Our Ignorance

Early on in his latest book, No Apologies: Why Civilization Depends on the Strength of Men, Anthony Esolen recounts the troubling tale of the Colonial Pipeline ransomware attack in May 2021. Russian hackers used a compromised password to insert malware into a vulnerable computer network, forcing the company to shut down its entire 5,500-mile network of pipelines that serves much of the East Coast. The stoppage disrupted fuel deliveries for five days. Alarmed commuters lined up for miles to pump rationed gasoline into their tanks while airlines canceled flights or added stops due to a jet fuel shortage in the Southeast.

Colonial paid the $4.4 million ransom to the hackers to bring the pipeline back online. Bad as that was, it wasn’t the most disturbing part of the story. When CEO Joseph Blount, Jr., appeared before the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee a month later, he explained the major reason it took nearly a week to get the gasoline flowing again.

“He testified that most of the men who could operate the controls on the pipeline have died or retired, so that the 5,500-mile line must rely almost wholly upon computerized systems for its operation,” Esolen writes. “That means, of course, that we are vulnerable to attacks by people who do not have to take a guard at gunpoint, or dig a big hole somewhere that no one will notice.”

“[O]ur technology has progressed to the point where, for a time, we can get away with running things on the cheap—and the irresponsible,” Esolen adds. Which is quite a shocking development when you think about it. As skills are lost and essential trades turn into weird niche professions, America risks forgetting how to keep the gears of civilization turning. And not just figuratively speaking.

It’s a massive problem. A nation that can no longer make and maintain things is a nation that is no longer truly independent.

In May 2021, Big Four accounting firm Deloitte reported that the “manufacturing industry netted a loss of 578,000 jobs during the pandemic-challenged year 2020—a figure that represents nearly six years of job gains, and yet, at any given moment in the past six months, nearly 500,000 jobs have remained open in manufacturing.” The report forecasted 2.1 million unfilled U.S. manufacturing jobs by 2030. Many manufacturers struggle even to find people for entry-level positions, which do not require special skills—just people capable of listening, learning, and following through. How hard can that be?

Yet, Deloitte says, “there is no indication whether this trend will reverse.” In fact, the U.S. manufacturing executives the firm surveyed said they believe finding the right talent is now 36 percent harder (a strangely precise number) than it was in pre-pandemic 2018. Executives fret openly over what options they may soon face: “Is there a point when we run out of production workers or a point when we have to consider moving to a different location?” To a different country, he means.

How We Got Here

No single factor can fully explain the decline in the skilled trades. But here are some reasons. This is not an exhaustive list.

Companies in the 1980s into the ’90s all but eliminated apprenticeship programs as a way of cutting costs—a decision many have come to regret and are now attempting to reverse, with limited success.

Profound changes in the economy played a role, too. U.S. manufacturing jobs peaked at 19.6 million in June 1979 and have been on the wane ever since, as ill-conceived “free trade” agreements and widespread globalization encouraged companies to move their factories south of the border, and overseas. The Great Recession wiped out 2.8 million manufacturing jobs, many of which never came back or took years to return.

Automation, obviously, has played a role, as jobs previously filled by humans have been supplanted by robots and machines that never take coffee breaks or paid vacations, and eventually “retire” without the need to collect a pension.

Fewer and fewer high schools offer the shop classes that were commonplace in the mid-to-late-20th century. Those classes taught millions of American kids—boys mostly—the right way to use a bandsaw and a blowtorch. They still exist here and there, including in California. But mostly, they dried up in the early part of this century, subsumed by George W. Bush’s “No Child Left Behind” law that placed reading and math proficiency at the center of everything. The goal was to “close the achievement gap” and send more Americans—especially women and minorities—to college. In practice, however, schools devolved into “teaching to the test” under a mandate of either reaching critical yearly benchmarks or risking the loss of crucial federal education funding. Electives like shop class didn’t stand a chance.

If it occurred to any one of those policymakers and education reform “experts” what they were trading away in the bargain, it isn’t evident even now that the results are in.

Baby Boomer retirements also have removed the invaluable experience and institutional memory that are essential to fostering new generations of tradesmen and craftsmen—an incalculable loss. Related, however, is the problem of widespread fatherlessness and family disintegration among the generations that followed the Boom. For those of us of a certain age who did have fathers, helping our dads “get the tools,” rotate tires, change oil, and replace worn brakes were sometimes annoying but vital rites of passage. (That’s become practically impossible now as modern auto repair has become the near-exclusive province of computer experts in coveralls.)

Yet it turns out, men are not as disposable as our woke culture would have us believe. As Esolen observes in No Apologies, “boys are not going to learn how to wield a sledgehammer from their mothers.” (Sorry, Girl bosses.)

A Faux Knowledge Economy

Maybe the skilled trades now are simply “jobs Americans won’t do.” If so, why not simply import those workers? Or outsource those jobs? Or both?

Trouble is, that’s exactly what we’ve been doing for nearly four decades—all but obliterating the middle class along the way. As America has become more of a faux “knowledge economy,” we’ve successfully dumbed down at least two generations of people who cannot change a tire, boil an egg, or balance a checkbook. (The good news? Apparently, they like to sew.) We’ve produced millions upon millions of well-credentialed but poorly educated, atomized people who need constant validation through their screens and who recoil from the slightest hint of risk.

America was founded as a republic that assumed its people were capable of self-government. Self-government implies a certain self-sufficiency in service of a common good. But the seismic cultural shift away from teaching the trades has helped make us more passive and dependent—less “citizen,” and more “subject.”

“What ordinary people once made, they buy,” Matthew B. Crawford writes in his 2009 book, Shop Class as Soul Craft. “And what they once fixed for themselves, they replace entirely or hire an expert to repair, whose expert fix often involves replacing an entire system because some minute component has failed.”

Crawford, a master motorcycle mechanic with a Ph.D. in political philosophy from the University of Chicago, argues that a passive consumer ethos has transformed Americans’ habits of freedom into habits of conformity and alienation. By restoring a culture in which the trades are again lauded as respectable and even honorable work, we might begin to restore some of the older, better habits of freedom and self-government. The goal—or one goal, at least—should be to achieve “a sociable individuality” that recognizes we possess rights and duties, and accepts that “we are basically dependent beings: one upon another, and each on a world that is not of our making.”

With that in mind, Crawford writes,

the special appeal of the trades lies in the fact that they resist [a] tendency toward remote control, because they are inherently situated in a particular context. In the best cases, the building and fixing that they do are embedded in a community of using. Face-to-face interactions are still the norm, you are responsible for your own work, and clear standards provide the basis for the solidarity of the crew, as opposed to the manipulative social relations of the office ‘team.’ There are surely other kinds of work that I am unacquainted with where these goods can be realized; it remains for others to explore them.

Alternative Paths to Meaningful Work

Crawford offers no specific policy solutions. He simply wants his readers to think differently about the proper role of work in life and perhaps act differently as a result.

To change the current culture, however, it will be necessary to change some laws. Bringing back shop classes would be a start—and probably a tall order. Loosening other rules might offer young people alternative paths to meaningful work without requiring a four-year degree and an attendant mountain of debt.

I’ll offer one example close to home: My son, who turned 20 last week, attends community college with the idea of eventually pursuing a career in forensic sciences, possibly as a crime-scene investigator. Last year, on his own initiative, he began contacting mortuaries to ask about apprenticeships. He thought that if he was going to work around dead bodies someday, he should become acquainted with working with dead bodies. Two family-owned funeral homes were receptive and sympathetic but had to turn him down. All of the larger corporate mortuaries rebuffed him outright, saying he would need to complete certified mortician’s training before they would even speak to him.

The death business, as with so much else in life, is heavily regulated in the Golden State. Often those rules are well-intended and serve a reasonable public purpose. But as a consequence, many businesses cannot offer apprenticeships even if they want to. Why couldn’t that be changed without undermining consumer protections or risking the mortuary industry’s insulation from upstart competition (which is what most licensure rules are really about)?

For now, my son works at a distribution warehouse for the second-largest retailer on the planet. (You know the one.) He’s learning a lot about how to operate and fix robots. He’s being trained to solve problems unique to the logistics business. He’s young and energetic enough to handle the sometimes-long hours and occasional physical demands while maintaining good grades in his classes. But he assures me warehouse work is hardly mindless, and the pay is just fine.

I asked him if he might change his mind about forensics. He told me he doesn’t think so but that he planned to stay in logistics for a while.

“It might lead to some interesting opportunities,” he said. “But if not . . . if forensics doesn’t work out, either, I guess I could always become a sheep farmer somewhere.” It would be useful, honorable work, anyway—a difficult and unlikely but decent trade for a young man unafraid of hard work and worthy of a good life in a free country.

I just hope that country is America.