In 1951, a 25-year-old Yale graduate published his first book, which exposed the extraordinarily irresponsible educational attitude prevailing at his alma mater. That book rocked the academic world and catapulted its young author, the aristocratic William F. Buckley, Jr., into the public spotlight.

This seminal work, written by one of the most courageous conservative thinkers of the 20th and 21st centuries, also laid the groundwork upon which numerous other media voices were built.

Buckley described how it all started when he was an undergraduate at Yale University from 1946 to 1950. He wrote from his conscience. Buckley was very precise in describing how he felt traditional American values were being ignored, undermined, and distorted by academics. He made his case by citing specific classes, instructors, and textbooks.

Bill Buckley earned the right to be the quintessential role model for conservatives and tradition because of his courage and gift for clearly and logically communicating his argument. His special accent and style didn’t hurt, either. There were no ad hominem fallacies. He confronted issues head-on. He even discussed his motive for writing the book (which caused quite a flap) by saying it was tied to his love for his alma mater and the country in general. By that, he meant his desire was for constructive change. It was by pointing out the errors that he hoped to achieve the positive resolutions he sought. Buckley remained a voice worthy of an audience in the marketplace of ideas for the over six decades of his life that followed.

In many ways, God and Man at Yale was the book that launched Buckley and the modern conservative movement in America. No one since has achieved his stature, voice, or credibility. His award-winning television show “Firing Line” was a fixture in my household, as was his opinion magazine, National Review.

I met Bill many times, first as a debater of some acclaim early in my undergraduate days in Boston and then at various NR events. We had one long exchange of letters over a speech I gave at St. Andrew’s School in Delaware on the themes in the 1981 film, “Chariots of Fire.” I quoted the lines of the film and Bill, it turns out, particularly respected the nobility of the character who played a British lord. I still have those letters and treasure that memory of a true intellectual exchange. He also liked that I used the phrase, “Don’t immanentize the eschaton,” a kind of hallmark of his own best thinking!

Buckley set the stage for what has become the most vibrant political and cultural force of our time: American conservatism. Many forces made this phenomenon happen, and those forces have influenced American culture, politics, economics, foreign policy, and all the other sectors of American life. Without Buckley and that first missive, none of this would have transpired.

The rise of conservatism in the United States since the 1950s has been one of the most important political developments of the age—not only for America but also for the world. But my story does not go back in time to see how or where it all began at Yale but instead moves into the present to see how much worse things have become at the venerable university.

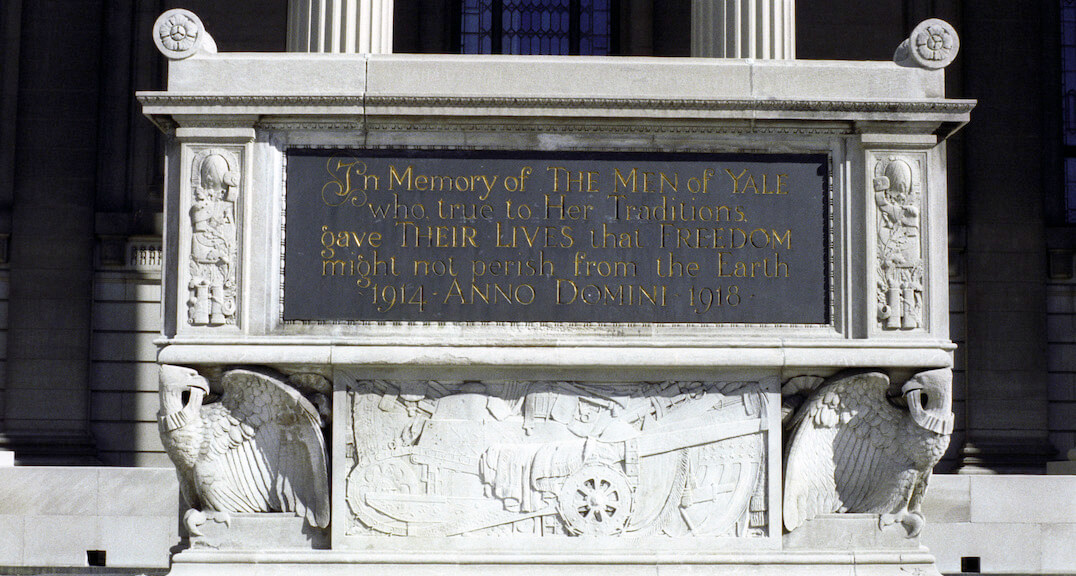

Yale’s deep roots may be traced back to the 1640s, when colonial clergymen led an effort to establish a college in Connecticut to preserve the tradition of European liberal education in the New World. That vision was fulfilled in 1701, when the charter was granted for a school “wherein Youth may be instructed in the Arts and Sciences [and] through the blessing of Almighty God may be fitted for Publick employment both in Church and Civil State.”

In 1718 the school was renamed “Yale College” in gratitude to the Welsh merchant Elihu Yale, who donated the proceeds from the sale of nine bales of goods together with 417 books and a portrait of King George I to the fledgling school.

Today Yale has matured into one of the world’s great and global universities. Its 11,000 students come from all 50 American states and from 108 countries. The 3,200-member faculty, supposedly, is “a diverse group of men and women who are leaders in their respective fields.” The only thing lacking is intellectual diversity, as leftism has become the agreed creed, not the Hebrew Bible that’s etched into the original college seal.

Yale As I Knew It

This is my tale about Yale. I had served on the boards of both the Episcopal Berkeley Divinity School at Yale and Yale Divinity School for six years each and was well known to the administration, fundraisers, and faculty alike. I was later on the faculty as a professor for five years. My WASPy sensibilities and pedigree fit well into the paradigm for Yale. For years they had a strategy to loot the high net worth of the east coast families and Yale alums in the establishment and run with their money—in precisely the opposite direction. I call it stealing from the rich to support the Left. It is an arrogant and obvious theft and, unlike Robin Hood, it is quite well camouflaged.

Many readers will recall when billionaire-philanthropist Lee Bass in 1990 gave his alma mater $20 million to establish a program studying Western civilization. The problem? Bass wanted the program to portray the West in a postive light. Yale couldn’t abide such a condition and returned the money in 1995, claiming the center wouldn’t be academic enough for the school’s notably leftist faculty.

My story is equally wicked.

I left the board at Yale in 2002, just before a dean was charged with embezzling funds from their accounts to pay for such things as his daughter’s education—at Harvard, of all places—and padding his own pocketbook. The story broke in the New York Times, and all hell broke loose. This deed occurred at Berkeley Divinity School—a school that no longer believed in an omnipotent God who created heaven and earth.

When I received a large multimillion-dollar grant followed by two smaller ones, I urgently needed to find a university at which to place the funds and conduct the research. At our house, Yale was number one—Lux et Veritas. My son, a world-renowned, all-Ivy rower, was a Yalie and into the secret society lore as well as the prestige of wearing the big Y on the blue shirt. He had so many victories in rowing we used the multiple t-shirts from his opponents to wash and dry our cars.

So even though I am a sorrowful Ph.D., and a “recovering academic,” I naturally chose Yale. I knew them, they knew me, and it felt right, though I still went in with some deep-seated suspicions.

I met with Miroslav Volf, a bald, bespectacled Croatian, who was Time magazine’s theologian of the year and had started something he called the “Center for Faith and Culture.” He was co-teaching a course with the former British New Labour Prime Minister, Tony (lapdog) Blair, on “Faith and Globalization.” Though he was an Eastern European of the neo-Marxist type, he was also a Pentecostal Christian—an odd combination, to say the least. Anyhow, while his ideas bothered me a bit, I decided to fit into that perch and park the project there so long as Yale gave me a multi-year contract as a full research professor, with all the salary and benefits one would presume. They caved and gave me everything but the free parking place (that cost a hundred bucks a month).

I had returned to Yale—back in the very belly of the beast!

It turned out Volf was a toxic person of the worst sort (ask his former executive director, the nicest guy on earth). While pretending to be a humane man, Volf could be ugly and disrespectful to his underlings and assistants.

I also discovered that he was an Islamophile. He penned a controversial book, Allah: A Christian Response, which asserted we all worship the same God. On the side, it was later disclosed he took lots of clandestine funding from the Muslim world, including one emir in particular from Jordan—which I suppose made him “unbiased.” He even eventually divorced his wife of many years to marry a grad student about 30 years his junior—but that kind of behavior happens all the time at universities. People just shrug and look the other way. As long as you go along with their left-wing agenda and don’t rock the boat—or kill anyone—you are safe. Heck, one anthropology professor, who was chairman of the department at one point, even slept with his very own Ph.D. student and then hired her.

Yale, it turns out, has sailed left of where Buckley departed it in the 1950s—way, way Left. Its right-wing truly starts with Barack Obama and moves quickly left to fever swamps of anti-Americanism, racial grievance, victimization, and green fanaticism that typifies American university life today. This is the strangeness of post-postmodernism, I suppose. And parents pay for this. At Yale, they pay a lot!

Keep Your Friends Close

I could name only six faculty of any, even moderate, conservative perspectives in the entire gigantic faculty while I was there. That’s less than two hands. One was a Straussian political philosopher who actually voted for Obama but believed in the American founding—a radically brave notion for Yale. Another was a law school professor who wrote on corporate reputation and belonged to the Federalist Society.

The one I cherished most and who became a close personal friend, from Montenegro via Claremont and Harvard, ran something called the Center for the Study of Representative Institutions, funded by the moneybag Jack Miller and oriented to liberalism with a small “l.” They made me a senior fellow. He was, however, almost lost due to the desires of the dean of the MacMillan Center—his boss and a kooky leftist—who said he was unwelcome at Yale but who kindly found him a position in Abu Dubai. Imagine that! Exiled to the Persian Gulf because you are a conservative at Yale. That’s how the system works nowadays.

There is no intellectual diversity. It is leftism or else. When Yale got $4 billion to open a non-degree granting campus in Singapore, the faculty voted 99 percent to turn the money down because the Asian economic powerhouse had an “authoritarian regime.” But Yale’s then-president, Rick Levin, took the money anyway.

When Buckley was at Yale, he noted where things were right and where they were headed south. Today, there is only the Deep South and Antarctica. It is a virtual monopoly of one opinion. There is no God (at all) and human beings are viewed as nihilistic materialist beings, soulless, and progressing to some kind of socialized future—once enlightened and tamed by the force of an all-knowing elite operating within an administrative state (mostly run by former Yalies, I suppose).

Virtue and Business

My research at Yale was on (good) virtuous companies. The idea that companies might be “good” upset a lot of people who believed especially all big businesses were basically evil. I only taught two courses at the graduate level with the management crowd and Ph.D. students on “Virtue and Business.” One student who took the classes actually asked, in all seriousness, “what is virtue?” He had never before encountered the term.

I did my own thing, publishing books such as Doing Virtuous Business, The End of Ethics, and Practical Wisdom in Management based on all the case studies we collected at the Yale School of Management. Fortunately, my grant paid for four post-doctoral fellows. I also co-authored a polemical treatise called America’s Spiritual Capital with the famous Loyola Catholic philosopher Nicholas Capaldi, who is, God-forbid, a libertarian. That angered a lot of people even more. How could a Yale professor defend America and write with an alleged right-winger? We even thought there was some Providence at work in the American founding. Such utter nonsense!

My theoretical contribution (appearing in scholarly journals) on what we termed “spiritual capital” did not go over all that well, either, with the social scientists or those who believed religion had (or should) wane (and the sooner, the better).

The dean of the divinity school, a liberal Catholic, was embarrassed to see me publish so much and speak all over the world. When my PBS documentary “Doing Virtuous Business” (which had $ 1 million in sponsorship from leading foundations) was nominated for an Emmy and aired on 150 stations to 15 million “viewers like you,” it was just too much publicity. In an airing of the documentary on campus, the faculty—not the students—questioned it for having too positive a view of capitalism.

The nefarious dean tried to cook my goose by interfering with another grant I was offered by a big Catholic foundation. His underlings reject it. “Conservatism or anything pro-business should not be funded” was the foregone conclusion at Yale. Instead, I had to sneak in a smaller grant (from Jewish patrons) onto the books to fund my work on crony capitalism and the financial debacle because Yale would not like that, either. When I attended Liberty Fund colloquia, the Mont Pelerin Society, or the paleo Philadelphia Society, Yale would not pay for my travel. Those conferences were deemed “political” in nature, as if what they professed was not. But their sentiments were approved as defensible, whereas mine were WASPy or traditional, and therefore out of bounds.

I was also barred from approaching donors—some Jewish, others Catholics, and others still Evangelical, all of whom wanted to support my work. Yale would not find it respectable to accept such contributions. One day, I brought a potential $50 million gift to the head of Yale’s development office, a lanky sophisticate of Germanic descent. Her office, high in the office tower with the best view in town, looked across the Elm City and its famous Green. To accept such a grant, she said, meant the faculty would have to choose the subject matter, and even then, that could change every five years to fit the needs of the university as it evolved (i.e., lurched further leftward). The donor and I got up, shook her hand politely, and said goodbye—and good riddance.

The one thing Yale did better than any state-run institution, however (even better than the old USSR), was bureaucracy. They had three full-time drones to oversee my grant who were otherwise unemployable in the real world but were unionized at Yale. They worked 20 hours a week but collected salaries of over $50,000 each as full-time employees and lots of benefits and long vacations. Their boss was a woman named Lynch, an ironclad battle-ax autocrat who was supposedly trained in finance but who didn’t have a clue, let alone a degree. She became my nemesis. Only threats of lawsuits forced her to back off. She was like those old East German border guards who let power go to her head. People called her “Stasi” behind her back.

When I left Yale after five miserable years, I felt as though shackles had been removed. “Free at last!” I cried.

Yale had degenerated into Sex Week (yes, just ask and you shall receive), endless gender studies, and streams of anti-Americanism, far worse than anything poor Bill Buckley would have remotely recognized. The Buckley Society, a student-led group, could quietly invite speakers to campus but only if they kept it a secret—lest there be protests around the likes of Steve Forbes (a capitalist tool) or the notorious Charles Murray (of the dubious Bell Curve).

Only behind closed doors and certainly not in the classroom could we openly discuss ideas—which used to be the very basis of any university. Today the basis of that purported education is simply and blatantly: indoctrination. Debunk everything, deconstruct reality, make everything about race, rid the students of the diseases of religion and class and, for God’s sake (Oh, there is no God, I forgot), by all means, redistribute the wealth (which, of course, was ill-gotten).

My parting shot at the university came during my final term, when the famous Yale Political Union invited me to be the keynote speaker in their esteemed debate program, which stretches back centuries. In front of about 800 students, the resolution was: “Embrace American exceptionalism.”

My argument was really a parting plea for the university to consider the exceptional nature of the country it is so determined to hate. Would such an argument even be allowed on campus today? I do not know—but I can say that my case for American exceptionalism found an audience at Yale, despite its near-total commitment to leftist propaganda.

American exceptionalism is the view that the United States occupies a special role among the nations of the world in terms of its national ethos, political, economic, and religious institutions, and its being built by immigrants.

The roots of the position date back to 1630 with John Winthrop‘s “City Upon a Hill,” although some scholars also attribute it to a passage of Alexis de Tocqueville, who argued that the United States held a special place among nations, because it was the first working representative democracy.

Belief in American exceptionalism has long been characteristic of both conservatives and liberals. The radical Marxist historian Howard Zinn, however, said that America’s exceptionalism is based on a myth and that “there is a growing refusal to accept” the idea both nationally and internationally. But he, of course, is dead wrong!

Many intellectuals across disciplines have argued that to deny American exceptionalism is to deny the heart and soul of this nation.

The exceptionality of America, politically, economically, militarily, and culturally is based on these facts:

1) The Protestant American Christian belief that American progress would lead to the Millennium.

2) The American writers who linked our history to the development of liberty in Anglo-Saxon England, even back to the traditions of the Teutonic tribes that conquered the Western Roman Empire.

3) Other American writers who looked to the “newness” of America, seeing the mass of “virgin land” that promised an escape from the decay that befell earlier republics.

Because America lacks a feudal tradition of landed estates with inherited nobility, it is arguably unique among nations. The Puritan Calvinists who first came to Massachusetts had a strong belief in predestination and a theology of Divine Providence that still has effects down to this day. Since God made a covenant with his “chosen people,” Americans are seen as of a different type. This “City on a Hill” mentality is still evidenced in American folklore, customs, and songs (“This land is your land, this land is my land, from California, to the New York island”). With its particular attention to immigration, America has been a beacon to the world for generations.

The Statue of Liberty itself is an embodiment of that ethos. America was also created on a vast frontier where rugged and untamed conditions gave birth to the American national identity and the narrative of a continent of exceptional people—explorers and adventurers. Think of my relative, Teddy Roosevelt, on winning the West!

The economics of the American founding was very much a Lockean affair: the protection of property rights in what was “the largest contiguous area of free trade in the world.” But you recall there were two competing views of America’s economy: a Southern Agrarian view, championed by Thomas Jefferson, and a Northern industrial or commercial view, championed by Alexander Hamilton. It is this same difference in visions that was at the economic root of the American Civil War, a war that saw the ultimate victory of industrial and commercial view.

Hamilton, as secretary of the Treasury, prevailed. He established the credit of the United States by consolidating state and national debt and paying the interest upon it and transformed it into capital by issuing certificates on it; established a national banking system; and thereby encouraged what he called “the spirit of enterprise.” Hamilton used the freedoms of the Constitution and its protections to create a capitalistic, free-market economy and ensured that the United States would “become the richest, most powerful, and freest country the world has ever known.”

The role of the government in such an economy has been well described by James Madison in Federalist 10:

A republic . . . promises the cure for which we are seeking . . . the same advantage, which a republic has over a democracy in controlling the effects of faction, is enjoyed by a large over a small republic.

To be a fit participant in a modern republic and market society such as America, it is necessary to be a certain kind of person in a certain kind of culture. This kind of person is one who internalizes his values and makes them work: a person of virtuous character. It is no accident that Max Weber identified none other than Benjamin Franklin as the epitome of the “Protestant work ethic.” Nor is it an accident that America remains the most philanthropic country in the world. Franklin was the quintessential American, an entrepreneur in every sense of the word, and a proponent of both thrift as a virtue and generosity as a practice.

Finally, as the Nobel Prize-winning author V. S. Naipaul has put it,

[the] idea of the pursuit of happiness . . . is an elastic idea; it fits all men. It implies a certain kind of society, a certain kind of awakened spirit. I don’t imagine my father’s parents would have been able to understand the idea. So much is contained in it: the idea of the individual, responsibility, and choice, the life of the intellect, the idea of vocation and perfectibility and achievement. It is an immense human idea. It cannot be reduced to a fixed system. It cannot generate fanaticism. But it is known to exist; and because of that, other more rigid systems in the end blow away.

One does not impose personal autonomy, which is the secret of America’s real and lasting power.

Human flourishing is an American moral theory that links virtue and happiness, specifying the relation between these two concepts as one of the central preoccupations of ethics. Virtue ethics today has been revived largely because of the American spiritual capital built up as a legacy over many centuries of eudaemonic thinking and practice. American exceptionalism is the very embodiment or the exemplar of the logic of modernity.

In Lincoln’s famous phrase, “America is the last, best hope of mankind.” And, to the extent that the logic of modernity is rooted in Judeo-Christian spiritual capital, America is unique in preserving that connection. Americans continue to identify themselves overwhelmingly with the Judeo-Christian spiritual heritage; long after it has disappeared as the cultural foundation of Western Europe. That is why most Americans subscribe to the Lockean liberty narrative and not the social democratic equality narrative that now dominates Europe; it is why America can combine a secular civil association with a religious culture instead of the belief in a theocracy; it is why America celebrates autonomy instead of the Asian belief in social conformity.

Early American settlers gave voice to a specifically Anglo-Protestant identity. As the Harvard scholar Samuel Huntington has argued, American identity has had two primary components: culture and creed. The creed is a set of universal principles articulated in our founding documents: liberty, equality, democracy, constitutionalism, limited government, and private property.

Our culture is Anglo-Protestant, specifically dissenting Protestantism. Moreover, the creed is itself the product of “English traditions, dissenting Protestantism, and Enlightenment ideas of the 18th-century settlers.”

One way of characterizing the early United States is to say that it inherited the logic of modernity and all of its institutions (the technological project [from Francis Bacon], economic freedom [from Adam Smith], political freedom [from John Locke], and legal freedom [common law]) from Great Britain. What distinguished the United States from England were three crucial things: the lack of a feudal class structure that dominated Great Britain down into the 20th century; an extensive virgin territory for applying it (the Louisiana Purchase); and, most especially, the opportunity for a multitude of dissenting Protestant sects, Catholics, and Jews to engage the new world with a religious fervor largely absent from the feudalistic state churches of Europe. It is important to remember how many of the original settlers were from dissenting protestant sects such as the Puritans, Methodists, Baptists, and Quakers.

America exemplifies the logic of modernity par excellence. That is why there is such a thing as the American Dream—which continues to draw people to our exceptional shores from the world over.

“My friends, Yale students, and pundits everywhere along the Yale Political Union party spectrum, I say to you: Embrace American exceptionalism!”

With these words, I closed my argument for American exceptionalism, and to my utter surprise and partly due to a clever debate technique employed in rebuttal (I quoted Barack Obama), we won the debate.

Yes, we won, but by a single vote. Even at Yale, America is still exceptional—just barely.