A few weeks ago in this space, I wrote about the hive mentality that stands behind the administrative state. In the course of that column, I quoted Glenn Ellmers on the shaky foundations of public morality. “What is left of public morality,” he wrote, is now understood in terms of ‘values,’ or subjective preferences based only on individual will. Even in the small handful of healthy institutions in civil society, the political and civil rights of the ordinary citizen rest upon a precarious foundation, threatened and undermined by the powerful claims of social progress.” What chance do an individual’s “subjective preferences,” his “values,” have against the tide of “social progress”? Not much.

This was something the historian Gertrude Himmelfarb analyzed with dispatch in her book The De-moralization of Society, which traces the path from “Victorian virtues to modern values.” Writing in the 1990s, Himmelfarb noted that “it was not until the present century that morality became so thoroughly relativized and subjectified that virtues ceased to be ‘virtues’ and became ‘values.’” That transformation is now so far advanced that can be difficult for us values-saturated moderns to distinguish the two ideas. But Himmelfarb is right. The evolution, or devolution, from virtues to values marked “the great philosophical revolution of modernity.” Among other things, it gave currency to the assumption that “all moral ideas are subjective and relative, that they are mere customs and conventions.” The idea of virtue, on the contrary, “had a firm, resolute character.” Virtues are objective in a way values are not.

Values, as we now understand that word, do not have to be virtues; they can be beliefs, opinions, attitudes, feelings, habits, conventions, preferences, prejudices, even idiosyncrasies —whatever any individual, group, or society happens to value, at any time, for any reason.

The difference between virtues and values is adumbrated by everyday language. “One cannot.” Himmelfarb points out, “say of virtues, as one can of values, that anyone’s virtues are as good as anyone else’s, or that everyone has a right to his own virtues.”

I was reminded of Himmelfarb’s important distinction when reading Stephen Soukup’s reflections on the Uvalde shootings in which he cites the philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre’s discussion, in his book After Virtue, of the replacement of virtue by what Soukup calls “a state of emotive expression, a condition in which feelings and sensations are elevated above objective reality and traditional conceptions of right and wrong, good and evil, etc.” Soukup broadens MacIntyre’s analysis, showing how it helps explain the structure and impetus of the administrative state. “Broadly,” he writes,

MacIntyre’s critique is that bureaucracy/management is emotive in practice. Because management is concerned EXCLUSIVELY with process, with means and NOT with ends, it is, almost by definition, an amoral scheme. Management is purportedly rational, but rationality can only apply to means, and therefore the ends become the purview of the manager/administrator who substitutes his own personal preferences for genuine moral positions.

In another column, Soukup glosses MacIntyre’s argument, arguing that “One of the greatest tragedies of the Enlightenment was the abandonment of virtue ethics.”

Prior to the Enlightenment, the entire history of Western Civilization—from (at least) the ancient Greeks right up to the American Founding Fathers—virtue ethics dominated moral philosophy and the expectations of moral people.

In brief, virtue ethics posits that the most effective and functional means by which to create a civil society, foster good citizenship, and encourage the pursuit of a ‘good life,’ is the identification, propagation, and encouraged PRACTICE of virtues deemed universally important and universally affirmative.

There is a lot to this point, and I thought it might be worth saying something more about the evolution of MacIntyre’s philosophy and his effort to reanimate the claims of virtue.

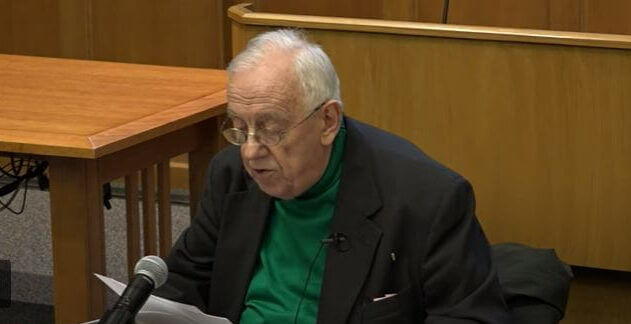

MacIntyre, who is still with us at 93, has had a long and distinguished career as an academic philosopher and public polemicist. Among other things, his mental and political itinerary provides a good illustration of the fact that few things are better calculated to garner attention than the spectacle of conversion, be it secular or religious. When After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory first appeared in 1981, it was not surprising that it should have caused a mild sensation, generating notice far beyond the purlieus of academic philosophy. Not only did the book present a bold thesis, suggesting as it did that the moral chaos of modern life might be overcome by rehabilitating certain aspects of Aristotle’s ethical teaching; it also appeared to represent a kind of conversion on the part of its author, the distinguished Glasgow-born philosopher and teacher.

Previously best known for his combative, Marxist-inspired ruminations on liberalism, ideology, and religion, MacIntyre now said goodbye to all that—well, goodbye at least to his old militancy—and came to the “drastic” conclusion that Marxism was every bit as bankrupt as liberal individualism. One no longer found him arguing, as he did in Marxism and Christianity (revised edition, 1968), that Marxism is “the historical successor of Christianity” and the only philosophy “we have for reestablishing hope as a social virtue.” By the time he wrote After Virtue, MacIntyre had decided that Marxism and liberalism both embodied “the ethos of the distinctively modern and modernizing world, and nothing less than a rejection of a large part of that ethos will provide us with a rationally and morally defensible standpoint from which to judge and to act.”

One might object that nothing is more “modern” than the ambition to reject “a large part”—the larger the better, it sometimes seems—of the modern world. But it was obviously not that aspect of the modern ethos with which MacIntyre quarreled. For him, the great curse of modernity is liberal individualism; and one of the main problems with liberal individualism is that it deliberately forsakes any substantive notion of the good, thus robbing moral language—and moral life—of an intelligible foundation. Liberal moral theory tends to be cheerful, permissive, relativistic—and quite empty. By appealing to a putatively universal rationality, it seems less particularistic and less culture-bound than other views of morality; but it is also less helpful in resolving important moral dilemmas.

In other words, liberalism does not dwell on the question of man’s proper ends. Instead, it offers an institutional framework within which individuals cobble together what answers they can from an unedifying process of compromise and debate. It is “the mark of a liberal order,” MacIntyre remarks, “to refer its conflicts . . . to the verdicts of its legal system. The lawyers, not the philosophers, are the clergy of liberalism.” Doubtless having to choose between lawyers and philosophers to preside over the commonweal is akin to choosing between Scylla and Charybdis. But MacIntyre’s point is that liberalism’s lack of allegiance to any positive conception of the good renders it ill equipped to provide a satisfactory response to the basic question, “What should I do?”

For MacIntyre, this is a crippling lack, one that is not shared by other traditions—what we might call “traditional traditions”—of moral inquiry. In his search for an alternative to liberalism, MacIntyre came to believe that the “key question” is whether “Aristotle’s ethics, or something very like them, [can] after all be vindicated?” As he put it near the end of After Virtue, “the crucial moral opposition is between liberal individualism in some version or other and the Aristotelian tradition in some version or other.” Two things above all attracted MacIntyre to Aristotle’s ethics. In the first place, Aristotle began by proposing specific answers to the question of man’s moral good. And secondly, Aristotle’s conclusions about morals consciously resulted from his response to a particular tradition of moral reasoning, one inherited largely from the heroic culture of Homer and from Plato.

In both respects, Aristotle’s ethics are the obverse of the ethics of liberalism. Where Aristotle advocated the practice of particular virtues—courage, justice, temperance, and so on—to achieve a well-defined moral end, liberalism begins with wholly abstract principles or “rules” of reasoning (of which Kant’s categorical imperative is perhaps the purest example), and regards the content of particular virtues and moral ends as secondary and relative. And where Aristotle consciously reasoned from a specific cultural tradition, liberalism typically aspires to formulate abstract, universally valid principles of moral reasoning. In After Virtue, MacIntyre puts the case for Aristotle and against liberal individualism, ending with the haunting suggestion that “we are waiting not for a Godot, but for another—doubtless very different—St. Benedict.”

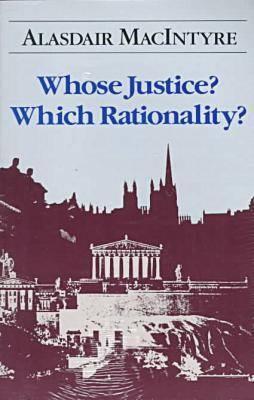

As it happens, MacIntyre later came to find the original St. Benedict more persuasive than he here implies. In the opening pages of Whose Justice? Which Rationality? (1988), the latter-day Marxist turned Aristotelian declares himself “an Augustinian Christian.” But the broad appeal of After Virtue lay less in any proposed saviors than in the extremity of its diagnosis. Beginning with the “disquieting suggestion” that the language of morality today is in a state of “grave disorder,” that it consists of little more than half-understood fragments salvaged from a disrupted tradition, MacIntyre charged that “we have—very largely, if not entirely—lost our comprehension, both theoretical and practical, of morality.” Though we are mostly unaware of this moral poverty, we are nonetheless “all already in a state so disastrous that there are no large remedies for it.” Hence MacIntyre concludes by recommending his version of counter-cultural withdrawal. “What matters at this stage,” he writes, “is the construction of local forms of community within which civility and the intellectual and the moral life can be sustained through the new dark ages which are already upon us.”

As MacIntyre was quick to acknowledge, many of his dour pronouncements in After Virtue deliberately echo Nietzsche. The foundation of moral discourse has been shattered (“God is dead”); culture has lost its moorings; values have become increasingly arbitrary and pointless; the optimistic ideals of liberalism have shown themselves to be hypocritical fictions—all this repeated Nietzsche’s analysis of the nihilistic bent of modern culture. But MacIntyre departed from Nietzsche in his judgment about how we should respond to the fragmentation of traditional values. Nietzsche preached a species of heroic individualism, epitomized by his doctrine of “self-overcoming,” the Übermensch, and his vision of an ethic “beyond good and evil.” MacIntyre, on the contrary, advocated a return to community and resuscitation of the virtues as understood by Aristotle.

Moreover, MacIntyre regarded Nietzsche as a late, largely unwitting representative of the very culture that he, Nietzsche, criticized so perspicaciously: the rootless culture born of the Enlightenment with its suspicion of tradition and its faith in a putatively universal moral reasoning. MacIntyre argues that one can discern “grounds for the authority of laws and virtues” only “by entering into those relationships which constitute communities whose central bond is a shared vision of and understanding of goods.” “To isolate oneself from [such] communities,” he maintains, “will be to debar oneself from finding any good outside oneself.” It follows that in MacIntyre’s view Nietzsche’s ideal of the completely autonomous, asocial individualist represents an extreme form of liberalism, not an alternative. If Aristotle is the presiding deity of After Virtue, Nietzsche turns out to be something closer to its resident nemesis. As MacIntyre put it in the title of one of his central chapters, the real choice is: Nietzsche or Aristotle?

Despite its sometimes aggressive polemic, however, the argument of After Virtue is essentially incomplete. MacIntyre himself stressed that his brief for Aristotle required a systematic account of moral reasoning if his case was to be persuasive, and that this account was left “unstated” in After Virtue. The book thus ends with a promissory note. Whose Justice? Which Rationality? was his attempt to make good on that promise. The bulk of the book—15 out of 20 chapters—is devoted to a detailed examination of three distinct traditions of rational inquiry and moral reasoning: the Greek tradition that culminated in Aristotle, the Augustinian Christian tradition from its Biblical origins through Aquinas, and the tradition of the Scottish Enlightenment that culminated in the skepticism of David Hume. Of course, as MacIntyre is quick to point out, this is hardly the whole story. The Islamic tradition, the Chinese and Indian traditions, the Jewish tradition: These and other major traditions of moral reasoning are left out of account here, as is the history of the Enlightenment tradition in Kant, Hegel, and their heirs.

MacIntyre’s rich historical exposition displays all the erudition and philosophical subtlety that his readers have come to expect from his work. And as always, he is nothing if not clear about his likes and dislikes. Aristotle, Augustine, and Aquinas come in for praise, while Hume, long one of MacIntyre’s villains, is repeatedly upbraided for his moral shallowness, lack of “candor,” and baneful influence. Perhaps the most impressive of MacIntyre’s historical chapters is “Overcoming a Conflict of Traditions,” in which he recounts Aquinas’ heroic integration of Aristotle and Augustine. Those acquainted with MacIntyre’s work will note that Aquinas is treated with greater sympathy and depth in these pages than he was in After Virtue. In part, this was no doubt due to MacIntyre’s recent conversion to Catholic Christianity. Given his emphasis on the importance of close-knit and like-minded communities for the propagation of traditions, it seemed appropriate that MacIntyre’s conversion found him moving from Vanderbilt University, where he taught for several years, to the University of Notre Dame, where still retains an affiliation.

Whose Justice? Which Rationality? starts by iterating some of the main complaints voiced in After Virtue. Once again, the theme of liberal modernity’s moral paralysis sounds through MacIntyre’s pages. Many of us, he writes—and the burden of the argument makes one realize that he means most of us—are not “educated into . . . a coherent way of thinking and judging, but one constructed out of an amalgam of social and cultural fragments” of promiscuous origin. His chief enemy here is the “post-Enlightenment” man who finds himself bound by no tradition, recognizing no overall scheme of belief beyond “pragmatic necessity,” regarding tradition as “a series of falsifying masquerades,” and speaking “the internationalized languages of modernity, the languages of everywhere and nowhere.” For such deracinated—but typically modern—men, entering into any tradition appears to be an arbitrary act of will, rationally unjustified: “beliefs, allegiances to conceptions of justice, and the use of particular modes of reasoning about action will appear to [such persons] as disguises assumed by arbitrary will to further its projects, to empower itself.”

Of course, the dominance of liberal individualism does not mean that other, older voices go entirely unheard. As MacIntyre notes, most of us in fact live “betwixt and between”: our sense of moral reasoning is fashioned in important ways by the dominant liberal individualist ethos but also draws sustenance from “a variety of tradition-generated resources of thought and action, transmitted from a variety of familial, religious, educational, and other social and cultural sources.” This may seem like a saving grace, but for MacIntyre the problem is that this “type of self,” which “moves from sphere to sphere, compartmentalizing its attitudes,” has “too many half-convictions and too few settled coherent convictions, too many partly formed alternatives and too few opportunities to evaluate them systematically.”

There are moments when MacIntyre’s polemic seems directed not so much at liberalism per se as at various extreme manifestations of the liberal spirit—at libertarianism, for example, which Allan Bloom once aptly summed up as “the right-wing form of the Left, in favor of everybody’s living as he pleases.” But it soon becomes clear that MacIntyre’s critique of liberalism is not confined to such extreme manifestations. Again and again, he attacks liberalism’s conception of an abstract “ideal rationality” that transcends social and historical context. Where traditional accounts of moral reasoning acknowledge that the “fundamental debate is between competing and conflicting understandings of rationality,” liberalism “presupposes the fiction of shared, even if unformulable, universal standards of rationality.” In the second edition of After Virtue (1984), MacIntyre had observed that “morality which is no particular society’s morality is to be found nowhere.”

In Whose Justice? Which Rationality?, this theme was repeated and developed in detail. There is, writes MacIntyre, “no neutral mode of stating the problems, let alone the solutions” of morality. The concept of rational justification “is essentially historical. To justify is to narrate how the argument has gone so far . . . [I]ndeed, since there are a diversity of traditions of enquiry, with histories, there are, so it will turn out, rationalities rather than rationality, just as it will turn out that there are justices rather than justice.”

MacIntyre’s main point is that we can only decide among competing moral claims from within a particular tradition, not from some ideal vantage point “outside.” Any abstract digest or inventory of arguments cannot help being misleading. “Yet it is just such abstraction,” MacIntyre writes, “which is enforced in the public forums of enquiry and debate in modern liberal culture, thus for the most part effectively precluding the voices of tradition outside liberalism from being heard.” It is liberalism’s fundamental blindness to the claims of tradition—more than any particular belief or lack of belief— that exiles it from a living appreciation of moral reasoning. As MacIntyre observes in his chapter on Aquinas:

Modern nontheological readers of Aquinas . . . may be apt to suppose that their difficulties in coming to terms with Aquinas’ relationship to tradition is a result of their alienation from his theology. In fact I suspect that it is characteristically the other way around. It is rather because the concept of tradition is so little at home in modern culture—and when it does seem to appear, it is usually in the bastardized form given to it by modern political conservatism—that they find it difficult to come to terms with Aquinas’ metaphysical theology.

In this sense, MacIntyre may be said to hold that moral reasoning is essentially parochial. There are no a priori answers to life’s fundamental moral questions. “How ought we to decide among the claims of rival and incompatible accounts of justice competing for our moral, social, and political allegiance?” MacIntyre asks. His preliminary answer is: “that will depend on who you are and how you understand yourself.” It follows that in his attempt “to say both what makes it rational to act in one way rather than another and what makes it rational to advance and defend one conception of practical rationality rather than another,” he will not simply propose another abstract, universal moral scheme. And it also follows that, when all is said and done, the corrosive sense of arbitrariness that modernity breeds can be defeated “only, it seems, by a change amounting to a conversion.”

Because liberalism presupposes a standard of moral reasoning that cannot in principle be met by any particular tradition, no argument for tradition will by itself be persuasive. Only a radical transformation of one’s point of view—amounting, as MacIntyre observes, to a conversion—will allow “this alienated type of self” to understand, let alone embrace, the claims of a particular moral tradition. Hence only some such “conversion” will be able to defeat the threats of relativism and moral emptiness with which liberal modernity confronts us.

Now there is much to admire in MacIntyre’s unflinching indictment of liberal modernity. His sensitivity to what we might call the historical embeddedness of moral traditions and his critique of the relativistic and often aggressively superficial ethic of Enlightenment liberalism make Whose Justice? Which Rationality? a valuable contribution to our understanding of the moral fabric of modernity. In Himmelfarb’s terms, he is an articulate partisan of “virtues” as opposed to “values.” Similarly, his distance from many of the reigning pieties of contemporary academic and journalistic wisdom leads to refreshingly independent judgments. What other academic moralist would dare to have described the New York Times as “that parish magazine of affluent and self-congratulatory liberal enlightenment”? Such lucidity and accuracy are rare.

But it is hardly surprising that Whose Justice? Which Rationality? failed to attract the level of interest that After Virtue enjoyed. For one thing, though billed as a sequel to that book, it was itself a prolegomenon of sorts, more a methodological than a substantive investigation. At one point, MacIntyre complains that in modern academic philosophy “gradually less and less importance has been attached to arriving at substantive conclusions and more and more to continuing the debate for its own sake.” Perhaps so. But this only increases one’s dismay when after some 400 pages of detailed historical and philosophical argument, MacIntyre tells us that he has arrived at a point where “we have to begin speaking as protagonists of one contending party or fall silent” and then alludes casually to the possibility of an “emerging Thomistic conclusion.”

In other words, at the end of his book he has come to the point where he can finally begin. The fact that MacIntyre has really been speaking as a protagonist all along—mostly, to be sure, in the guise of being an antagonist of modern liberalism—does not provide much consolation to readers who might have hoped for more substantial, more constructive insights. It is not clear to me that he managed to make a more satisfying case in either of his major sequels, Three Rival Versions of Moral Inquiry (1990) or Dependent Rational Animals (1999).

I applaud MacIntyre’s efforts to resuscitate the Artistotelean-Thomistic notion of virtue. But his argument is haunted by a thoroughgoing hostility toward the modern liberal spirit as well as a tendency to romanticize traditional modes of moral reasoning. Together, they sometimes weaken his criticisms and rob his argument of plausibility. While discussing the plight of higher education in an age hostile to tradition, for example, MacIntyre observes (ruefully, one can’t help thinking) that the abolition of religious tests was at “the foundation of the liberal university.”

No doubt he is correct that requiring such tests for university appointments and matriculation assured “a certain degree of uniformity of belief in the way in which the curriculum was organized, presented, and developed through enquiry.” And he is also correct that when religious tests were abolished universities were not suddenly transformed into institutions in which “contending and alternative points of view of rival traditions of enquiry could be systematically elaborated and evaluated.” On the contrary, what we have seen in higher education is the institutionalization of an illiberal, politically correct culture of pseudo-diversity that puts a premium not on fostering “contending and alternative points of view” but rather on a stultifying intellectual, moral, and political conformity. But this is not to say, as MacIntyre suggests, that universities were somehow more given to entertaining rival points of view or debate about fundamental issues in the days before religious tests were abolished.

In fact, MacIntyre’s remarks on the ills of higher education in the humanities epitomize both the strengths and the weaknesses of his position. He is right that the dominance of relativism in the universities has done “most harm . . . to the humanities, within which the loss of the contexts provided by traditions of enquiry increasingly has deprived those teaching the humanities of standards in the light of which some texts might be vindicated as more important than others and some types of theory as more cogent than others.”

It is difficult to disagree. But MacIntyre then goes on to castigate so-called Great Books programs for having a smorgasbord, un-historical approach to education, an approach in which “a student moves in rapid succession through Homer, one play of Sophocles, two dialogues of Plato, Virgil, Augustine, the Inferno, Machiavelli, Hamlet, and as much else as is possible if one is to reach Sartre by the end of the semester.” What this provides, he charges, is not an introduction to the culture of past traditions but “a tour through what is in effect a museum of texts.” For the same reason, he dismisses as intellectually bogus the notion of “Western values” propagated by “self-proclaimed contemporary conservatives, such as William J. Bennett,” who in MacIntyre’s view merely represents “one more stage in modernity’s cultural deformation of our relationship to the past.”

It is worth pausing for a moment to consider this handful of MacIntyre’s displeasures. There is no doubt that the kind of Humanities 101 survey courses that he ridicules tend to be superficial and to slight historical context. But what is the alternative? Would he prefer that students remained entirely innocent of the Western literary and philosophical heritage? Of course one might wish that students spend an entire semester each on Homer, Virgil, Plato, Dante, and so on, reading all of the works in the original language. But is that ever going to happen with more than the smallest number of students? Moreover, might it not be that those humanities survey courses in fact serve more to introduce than to complete a student’s education, inaugurating those with the talent and disposition into the riches of the tradition?

One might raise a similar objection to MacIntyre’s obiter dictum about former Secretary of Education William Bennett. No one would suggest that Bennett’s once-famous writings on education supplied the last word on this formidably complex subject. But that is hardly the point. We live, alas, in an imperfect world, and when we come to the kinds of issues that MacIntyre raises so passionately, our concern must be not only with abstract philosophical sophistication but also with practical consequences. To quote one of MacIntyre’s former heroes: What is to be done? That is the real question. Given the state of our schools and universities—given, that is to say, the very cultural fragmentation and loss of rootedness in tradition that MacIntyre bewails—were not William Bennett’s proposals for educational reform and a “Great Books” approach to education steps in the right direction? They were indeed. And if we compare the state of higher education circa 1990 to its situation today, when the ideology of identity politics and woke hysteria have undermined the entire educational establishment, those apologies for Great Books programs, for all their limitations, look pretty good.

There is another feature of MacIntyre’s argument that bears special attention. I believe it was William Blake who observed that an honest man may often change his opinions but never his principles. In his long journey from Marxism to Aristotelianism to Catholicism, MacIntyre naturally had occasion to change many of his opinions. But his principles would seem to have remained largely unaltered. Already in Against the Self-Images of the Age, MacIntyre’s 1971 collection of essays, we find him criticizing the ideal of a universal, culturally disembodied moral reasoning, insisting instead that rationality is “an inescapable sociological category,” unintelligible without reference to a particular cultural and historical situation.

Even more striking is the deep suspicion of liberalism and the modern liberal state that is patent throughout MacIntyre’s writings. Indeed, an avowed animus toward the ethos and principles of modern liberalism is something of a constant in his work, providing an important continuity between Marxism and his later, “conservative,” writings. True, near the end of Against the Self-images of the Age MacIntyre professes respect for the quintessentially liberal values of “toleration and of freedom of expression.” But he then complains that “liberalism by itself is essentially negative and incomplete,” explaining in one revealing passage that the precepts of liberalism “set before us no ends to pursue, no ideal or vision to confer significance upon our political action. They never tell us what to do” (my emphasis).

This is no doubt correct. But is it necessarily such a bad thing? Liberalism’s lack of a substantive notion of the good—its inability to “tell us what to do”—undoubtedly places great moral demands upon the individual. But it may also free him from the yoke of traditions that have outlived his belief or allegiance—allowing him, for example, to move from being a skeptical Marxist to being an ardent Aristotelian to being a professing Catholic according to the dictates of his judgment. And it should also be noted that the consequences of liberalism are by no means always as gloomy as MacIntyre’s analysis would lead us to believe. If liberalism is philosophically problematic, it has nonetheless proven to be extraordinarily productive politically. Indeed, among the chief political fruits of liberalism has been the modern, democratic state. This includes, of course, the United States, that bastion of “post-Enlightenment” men and women who, for all their alleged rootlessness, enjoy—as MacIntyre, having chosen to live in their midst, must know—an unparalleled measure of political and social freedom.

Reflecting on MacIntyre’s inquiry in Whose Justice? Which Rationality? often brought to mind a passage from Hermann Broch’s great philosophical novel The Sleepwalkers (1932). In a series of interwoven sections entitled “The Disintegration of Values,” Broch notes that in the modern age values are “no longer determined by a central authority.” Like MacIntyre, Broch points out that one result of this situation is that values that were once integrated into a coherent whole begin to splinter into separate, autonomous spheres, each with its own claims and goals: “war is war, l’art pour l’art, in politics there’s no room for compunction, business is business—all these signify the same thing, all these appertain to the same aggressive and radical spirit.” But unlike MacIntyre, Broch stresses that the disintegration of values confronts individuals not only with a critical loss but also with a powerful temptation: the temptation to evade the reality and consequences of disintegration. Broch writes:

One cannot escape from [the] brutal and aggressive logic that exhibits itself in all the values and non-values of our age . . . . [Y]et a man who shrinks from knowledge, that is to say, a romantic, a man who must have a bounded world . . . and who seeks in the past the completeness he longs for[,] has good reason for turning to the Middle Ages.

From the perspective afforded by Broch’s meditations, Alasdair MacIntyre appears to be something of a romantic—a severe, Thomistic sort of romantic, admittedly, but nevertheless someone quite different from the “conservative” his recent conversions to traditional moral doctrines have led many (even, perhaps, MacIntyre himself) to assume. In recoiling from the fragmentation of values that characterizes modernity, MacIntyre has presented less an alternative to the depredations of liberal individualism than an escape from its challenges. For better or worse (probably for better and for worse), we modern men are “cautious,” as Nietzsche said in The Gay Science. “Our mistrust lies in wait for the enchantments and deceptions of the conscience that are involved in every strong faith, every unconditional Yes and No.” We hesitate before bestowing unconditional affirmations or denial because we see in such professions the possibility of “enchantment and deception” as well as salvation. MacIntyre’s professions made him a stern and often insightful critic of liberal modernity. But they have also prevented him from doing justice to its achievements.