Our first president approached his Supreme Court appointments in a way that is in sharp contrast with today’s assumptions. You will not be surprised to find that George Washington had a quite different view of “merit” than recent presidents. Not to say Washington didn’t in some way presage the modern criteria for choosing justices. He appointed a few sitting judges as well as lawyers from elite educational backgrounds. But he did not choose only those sorts of justices. He chose entrepreneurs and prominent lawyers. He chose politicians and diplomats. He chose former governors and senators and elected officials of all stripes. Above all he chose giants of the legal profession from all over the new United States. The single uniting factor among these justices was their reputation as lawyers and their work in drafting or ratifying the new Constitution.

Article III itself is notably thin on the makeup of the Supreme Court. It is largely silent on the qualifications for justices or even how many there would be. It does not even require that the justices be lawyers! Washington was truly working from a blank slate when he appointed his justices. Originalists should pay special attention to Washington’s selections, since they are our best information on the founders’ vision for the Court and who should serve on it.

Washington took his responsibility to select the justices very seriously. He knew that the Court would be on the front lines of the ever-controversial issues of federalism and the division of powers, and he understood that the survival of the new country depended upon finding consensus when possible, so he endeavored to choose wisely. Of course, this meant appointing brilliant justices who would bring honor and excellence to the new Court. But more importantly, Washington wanted justices who had wrestled with the separation of powers issues that dominated the day and jurists who could unite the country around the new Constitution. Washington had no idea how the Court would handle the knotty issues of separation of powers and state’s rights. Nor did he choose only partisans who had pledged a particular approach to those problems. Instead, Washington tried to appoint a particular kind of patriot to the Court: individuals who had worked hard to draft or ratify the Constitution, rather than trying to find a particular judicial approach or philosophy. Washington was famously against factionalism, so he would likely be particularly horrified to find that today’s justices must pass a series of political litmus tests before nomination.

Washington’s justices share some common characteristics. All of them except for Samuel Chase were either involved in the drafting of the Constitution or strong advocates for its ratification, and often both. Most of them were also heavily involved in drafting their own state constitutions.

All of them (with the possible exception of William Cushing) were exceptional lawyers, and among the very best lawyers in their respective states. Lawyers of this era handled every flavor of case and controversy, so these justices cut their teeth in courtrooms and contract drafting.

Almost all of these justices had spent time reading the law as apprentices in the offices of prominent lawyers. Reading these biographies makes you appreciate just how much the “right” apprenticeship mattered. Many of these justices rose to the top of the legal profession partially because they apprenticed for an earlier leading light. Some of these apprenticeships are clearly the result of family connections, but several other justices were young men of little wealth and no family name who gained great apprenticeships through hustle, ability, and guile.

Every one of these justices was a giant in the public life and governance of his home state. Only Iredell and Cushing were not elected politicians during their careers, and they were deeply involved in state governance as judges and advocates. Each of the other eight justices were well-known and highly successful politicians.

Many of these justices were entrepreneurs and risk-takers (sometimes to their personal detriment), a marked difference from the more cautious, resume-driven justices we have today. It is worth remembering that the winners in the Revolutionary War were the rebels, so the prominent lawyers of the new republic were all gamblers. Still, it is remarkable to see that three of Washington’s justices faced serious financial troubles from failed investments and that six of them were heavily involved in outside business interests like land speculation or running an ironworks.

Washington also placed a heavy emphasis upon geographic diversity. Nine of his first 10 justices came from different states in the Union (in order—New York, South Carolina, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Virginia, North Carolina, Maryland, New Jersey, and Connecticut). This was not accidental. Contemporary sources establish that Washington wanted to make sure that the Court was balanced geographically so that each state had some stake in the new Court and Constitution.

It may sound odd to contemporary readers, but Supreme Court justices were among the most public-facing members of the new federal government in the 1790s because of circuit riding. The original justices spent much of their time on the road, sitting as district court or appellate judges on a circuit ride all over the country. The original federal court design included no separate circuit courts, so the justices handled any intermediate appeals as well as Supreme Court appeals. Washington’s justices faced a very light Supreme Court docket, but a very heavy burden traveling to hear cases in every state in the new country. The justices were on the road for the majority of the year, so Washington wanted to make sure they were familiar with the local laws and cultures.

Many of these names are now long forgotten, but reading their life experiences together, one cannot help but be staggered by the rich lives of our founding jurists.

John Jay

Washington’s first appointment to the Court was perhaps his most inspired: the great John Jay. Often overlooked among the founding fathers, Jay played a key public and intellectual role in the creation, growth, and survival of the United States. He is also a peculiar hybrid of the new school and old school model of Justice. He went to the finest schools, had a tremendously helpful apprenticeship, and forged over time the resume of an inveterate hoop-jumper. Yet he hardly lived a cloistered life. Few Americans of any era have accomplished more in public life than Jay.

John Jay was the eighth of 10 children. Three of his siblings died before adulthood, and two were struck blind by the smallpox epidemic of 1739. From Jay’s childhood forward he had every academic opportunity. His mother taught him English and Latin grammar. At the age of 11, he moved in with the Swiss Reverend Peter Stoope for official tutelage. Jay’s instruction was primarily in French, making him multilingual at an early age. In 1760, at the age of 14, Jay headed to King’s College in New York City (now Columbia). The King’s College curriculum was based upon those of Cambridge and Oxford, so the young student learned Greek, Latin, and some philosophy and natural law.

Jay decided to pursue a career in law. He graduated in 1764 and was fortunate enough to be hired as a clerk in the law office of Benjamin Kissam, among the most prominent and successful attorneys in New York City. The clerkship was doubly fortuitous, because from 1756 until 1764 attorneys in New York agreed to hire no clerks at all in an effort to limit entry to what they deemed an overcrowded bar in the city. This meant that Jay entered apprenticeship just as the freeze ended, a stroke of excellent luck. (It is also amusing to note that lawyers as far back as 1756 were working together to restrict access to the profession for economic reasons. As Adam Smith’s 1790 masterwork, The Wealth of Nations, famously noted: “People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices.” America’s long history of limiting entry into the legal profession out of self-interest thus predates the country itself.)

Jay initially formed a partnership with another famous son of New York City, Robert Livingston, Jr. A legal partnership was almost unheard of in pre-Revolution New York. Most lawyers ran their own office in a manner quite like today’s solo practitioners. But times were tight for lawyers and Livingston and Jay successfully leveraged their joint family connections into a successful shared practice. The partnership ended in 1771 when Jay’s practice grew large enough to support itself. By the eve of the Revolution, he was one of the best-known and most successful lawyers in New York City.

New York by 1774 was already the commercial and legal heart of the colonies, and Jay had established himself as one of its finest lawyers. Here his long and distinguished career in public service began. Jay was selected as a New York delegate to the Continental Congress in 1774 and served through 1779. Jay was a moderate from the beginning, avoiding the extremes of either loyalism or the most passionate advocates of revolution. In 1775, Jay helped draft the Olive Branch Petition in a last-ditch effort to avoid war with Britain.

From 1776-1777, Jay also served as a delegate to the convention drafting New York’s new constitution. Following its ratification, Jay was appointed the first chief justice of the newly created New York Supreme Court. Jay served in that role until 1778, when he was appointed president of the Second Continental Congress, the highest executive position in the new American government. Jay took the position in the heat of the Revolutionary War and at a time when its outcome was far from certain.

Jay did not participate in the drafting of the new Constitution because of his duties as secretary for foreign affairs. He did, however, play a critical role in its ratification. Jay joined Alexander Hamilton and James Madison in drafting the Federalist Papers, which described the benefits of the new Constitution and argued for its ratification. Jay wrote papers 2 through 5 and then fell ill, returning to draft number 64. Jay’s contribution is notable for the work itself but also for the heft and gravitas he brought to the argument when the authors eventually became known.

Jay also wrote an influential pro-ratification pamphlet titled “An Address to the People of the State of New York.” Jay’s efforts came to a head during New York’s ratification convention, which lasted 40 days and was a squeaker. New York became the critical ninth state to ratify the Constitution by a vote of 30-27. Jay was pivotal. John Adams described Jay’s role in ratification of the Constitution as “one of more importance than any of the rest, indeed of almost as much weight as all the rest.”

When Washington became the first president under the new Constitution he offered Jay the post of secretary of state out of respect for Jay’s abilities and diplomatic experiences. Jay declined, apparently seeking a break from international travel and negotiation. Washington then offered the position of chief justice of the new Supreme Court, which Jay gratefully accepted.

Consider the full breadth of Jay’s achievements before joining the Court: He had served as the chief executive officer of the United States. He had been the chief justice of New York’s highest court. He had been an enormously successful practicing lawyer and a tremendous student at King’s College. He had worked on the Federalist, still one of the greatest American writings on our government. He had been America’s top diplomat for years, handling the most sensitive and important international tasks, including helping to negotiate the treaty that ended the Revolutionary War. Perhaps it’s unfair to compare Jay’s resume to those of current chief justices: hardly anyone covers as much ground now as Jay did then. Nevertheless, if one considers Jay (and later Oliver Ellsworth and John Marshall) to be the model for what chief justices should be, we have been running at a loss since Earl Warren.

Jay’s career during and after his tenure on the Supreme Court is a great window into the type of individuals that originally served as chief justice. Jay spent his last term as chief justice (1794–95) in England negotiating the Jay Treaty of 1795. Britain and France were at war. Opinions in America, and in George Washington’s cabinet, were split. Some strongly advocated joining the war on France’s side. Others favored neutrality. Fans of the play Hamilton will know that this debate was covered in the hilarious rap battle between Hamilton and Jefferson, “Cabinet Battle #2.” At the same time, tensions were rising with Britain over trade issues, the continued placement of British troops east of the Mississippi in the Ohio Valley, and seizures of American ships in the French West Indies.

While Jay was in England negotiating the treaty he learned that he had been elected governor of New York. Jay returned to the United States and resigned from the Supreme Court to serve two three-year terms as governor. To modern readers the decision to leave the chief justiceship to pursue other interests will read quite strangely. For our current justices their role on the Court is a culmination of their life’s work. Why would they ever resign for another job? But Jay’s term as chief justice was just one of the many achievements in a life filled with service to his country and his state.

Jay shows us the sort of well-rounded and experienced leader that Washington sought for the Supreme Court. A person who had excelled not just in school or as a judge, but in every aspect of public life. Washington himself put it well when he wrote to Jay sending him his commission as chief justice, aptly praising Jay’s “talents, knowledge, and integrity” as the qualifications necessary to head “that department which must be considered as the keystone of our political future.”

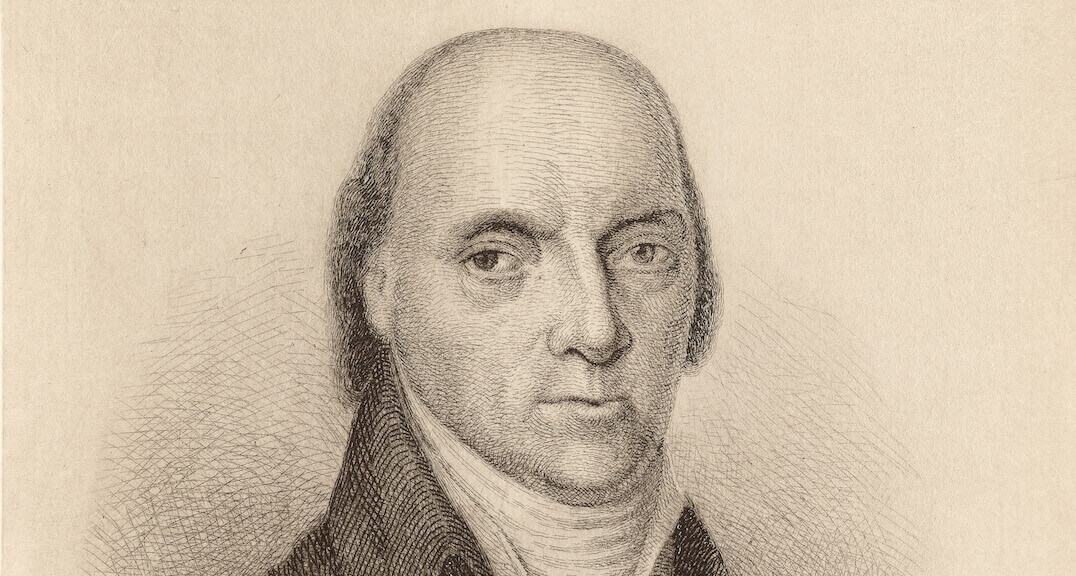

John Rutledge

Washington’s second appointment to the Supreme Court, John Rutledge, had one of the strangest careers of any justice while on the Court. Washington actually considered three people for the inaugural chief justice: Jay, Rutledge, and James Wilson. When Washington settled on Jay, he made Rutledge the Court’s second justice. But Rutledge never actually sat with the whole Court during his first stint, leaving the Court after a year and a half to become the chief justice of the South Carolina Court of Common Pleas (the highest judicial office in the state). When John Jay resigned as chief justice in 1795, Rutledge wrote Washington and asked for the job. Washington recess appointed Rutledge as chief justice, and Rutledge actually sat as chief justice and heard cases for six months before political headwinds and rumors of mental illness led the Senate to reject his nomination, the first time a presidential appointment to a major office had not been confirmed by the Senate.

Rutledge was born to a wealthy and politically connected family in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1739. Rutledge’s family, and eventually Rutledge himself, generated much of their considerable income from plantation property and slaves. As a teenager Rutledge read law and apprenticed in the law office of his uncle, Andrew Rutledge. Andrew Rutledge was speaker of the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly and also a prominent lawyer. John followed up his apprenticeship with three years of legal study at the Middle Temple in London. In the pre-revolutionary period there was no more prestigious start to a lawyer’s career than a trip to the Middle Temple in England. This was partially because of the perceived excellence of legal training in London, then arguably the greatest city in the world, but also due to the sheer expense of the education. To put the expense into perspective, when it looked like apprenticeships were going to be barred in New York City, John Jay’s quite wealthy family looked into sending Jay to London and the Middle Temple, but decided the cost was too prohibitive.

Rutledge served in a series of high-profile elected and appointed political offices, often while maintaining his law practice. He was elected to the South Carolina House of Commons three months after returning in 1761 and served in that body continuously until 1778. The Crown appointed him attorney general for the colony from 1764 to 1765. Rutledge represented South Carolina in the First and Second Continental Congresses. As the Revolution began Rutledge returned to South Carolina to help draft the state’s first constitution. He was also named president of the South Carolina General Assembly from 1776 to 1778, serving as the lead executive in the state during the height of the war. Rutledge’s order to protect Fort Sumter at all costs led to the first American victory in the Revolutionary War. Rutledge remained the chief executive throughout the war, suffering through the British siege and capture of Charleston and leading the eventual American liberation of the city in 1782.

After the war, Rutledge served as governor and as a judge in the Chancery Court for South Carolina. In 1787, he served as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention and was an active participant, advocating, among other things, against the direct election of representatives. Rutledge also served on the influential Committee on Detail (along with his future fellow justice, James Wilson) that helped draft the compromises that resulted in the final version of the Constitution. When Rutledge returned to South Carolina he was instrumental in ratification efforts.

If John Jay had taken Washington up on his offer to become secretary of state, Rutledge might well have been the nation’s first chief justice. Instead Rutledge had to settle for becoming the first associate justice.

William Cushing

Washington’s third justice, William Cushing, is less impressive than either Jay or Rutledge, both of whom were supremely talented lawyers and statesmen. Cushing was less so, and thus he’s the first (and hardly the last) relative mediocrity to reach the Court.

Like Jay and Rutledge, Cushing came from a wealthy family. His father and grandfather were judges and members of the Governor’s Council in Massachusetts. Like Jay and Rutledge, Cushing had a first-class education as the first “Harvard man” to join the Court. Cushing graduated with an A.B. in 1751, then followed in his family’s footsteps and read the law in the office of prominent Boston attorney Jeremiah Gridley. Cushing joined the bar in 1755 and opened a solo practice in his hometown of Scituate, Massachusetts.

Thus far Cushing’s biography sounds quite similar to Jay and Rutledge’s: wealthy family, excellent education, strong foundation in apprenticeship. Cushing’s experiences in the practice of law, however, were quite distinct, mostly because contemporary sources suggest he was not a very good lawyer.

First, Cushing could not garner enough business to make it as a lawyer in Scituate, where his father and grandfather had been prominent lawyers and judges. A bad sign for future prospects, surely. Family connections alone should have floated Cushing in Scituate. Instead, he decamped to the northern frontier in Lincoln County, near modern-day Dresden, Maine. Cushing gained an appointment as the justice of the peace for the county and also went north with a number of logging interests as clients. Given that logging was the main commercial activity that far north, and that Cushing was simultaneously serving in the main judicial office, he should have been well positioned for success.

Nevertheless, Cushing’s practice failed to thrive. Herbert Alan Johnson’s short biography of the future Justice presents a brutally unfavorable assessment:

Despite [Cushing’s] professional advantages, he achieved more success in business ventures than in practice. . . . Eventually Cushing lost his corporate clients to other attorneys. . . . Among Cushing’s private papers there is ample evidence that the suspicions of his clients were not without adequate foundation. . . . Throughout his life Cushing was unsure of the law. [W]ithout powerful family connections and a winning personality, such an attorney would never have survived in the highly educated and articulate bar that produced a practitioner of the caliber of John Adams.

Cushing was saved by his father, who pushed for his appointment as a judge on the Superior Court of Massachusetts. Cushing served in that role, first under the loyalist government and then under the new commonwealth, from 1772 to 1789, serving as chief judge (the highest judicial office in Massachusetts) from 1777 on. In this role, Cushing’s primary success seems to have been keeping his job despite the shifting political winds. One reason why there were few former judges with lengthy careers for Washington to choose from was that most royal courts were, unsurprisingly, not super friendly to non-loyalists, so many of them lost their jobs (or even their lives) during or after the war. Cushing somehow managed to serve as a loyal judge in the royal courts and then shifted into roughly the same office postwar, even gaining a promotion.

Part of Cushing’s success was his perceived fairness as a judge of the royal courts. Another part was family connections. But perhaps the single biggest factor was Cushing’s willingness to keep riding circuit and hearing cases throughout the Revolutionary War, while his colleagues avoided combat areas. Avoiding combat sometimes meant avoiding most of the state. Nor was the danger limited to official combat forces. In 1779, Cushing arrived in Berkshire County, Massachusetts, to hear cases in the middle of the riots of the Berkshire Constitutionalists. Cushing canceled court and was fortunate to escape unharmed, but for Cushing to retreat at all was an exceptional occurrence. Typically, he just held court as per usual. Cushing’s willingness to ride circuit during wartime, riots, bad weather, and any number of other obstacles paid off in the post-Revolutionary period. As Woody Allen has noted, “80 percent of success is just showing up.” Cushing embodied that attitude unfailingly.

Washington appointed Cushing to the Court in 1789 as America’s third justice, and he served until his death in 1810, sitting under four different chief justices and offering critical support to John Marshall. Nevertheless, Cushing was not an ambitious man; despite his years on the Court he left a limited jurisprudential legacy. Johnson’s biography of Cushing presents a portrait of a relatively silly person:

[W]hen Cushing arrived for the first sitting of the Court in New York City he wore his old-fashioned full-bottomed judicial wig. About one hundred little boys followed him down the street, watching him with curiosity and awe. The crowd grew and gradually it dawned upon the Justice that he was the object of unusual attention, although he did not know the reason why. Finally a sailor was astonished into exclaiming, “My eyes! What a wig!” The new Associate Justice of the Supreme Court returned to his hotel room, ordered a peruke maker to prepare a more fashionable headpiece for him, and was never seen again in his judge’s wig.

Other evidence of Cushing’s relative lack of ambition was his decision to decline an appointment as chief justice. When Jay resigned and Rutledge was rejected by the Senate, Washington turned to Cushing. He actually initially said yes to Washington’s request, and his one semi-official act was to sit at Washington’s side at a dinner party in the seat of honor as the new chief justice of the Supreme Court. Apparently this experience was too much for Cushing. Later that week he declined the appointment for reasons of health but stayed on as an associate justice and served another 15 years in that role.

Cushing is now a barely remembered Supreme Court justice who wrote a small number of relatively straightforward opinions. In fact he’s probably best known for declining to become the chief justice. He is surely among the least noteworthy justices to ever serve on the Court: though he served for over 20 years, he wrote only 19 opinions, each of limited scope. Nor were these cases of particular note. Here’s the CQ Press’ summary of Cushing’s service: “Cushing delivered only nineteen brief opinions during his twenty-one years on the bench, and his decisions were direct, noncomplex, or as some have said, ‘simple.’ If succinctness is a blessing, then Cushing was a saint.”

James Wilson

James Wilson’s is surely among the most bizarre Supreme Court stories. His tale begins with a rapid ascent from relative destitution in Scotland to a classic American immigrant success story. He was a brilliant political philosopher, a lawyer without peer, a leading light at the Constitutional Convention, one of America’s first law professors, and a land speculator.

Unfortunately, the last role led to Wilson’s downfall. He borrowed heavily to build his empire and his debt issues eventually grew so unwieldy that he was thrown into debtor’s prison while he was a sitting Supreme Court justice, and he died in relative ignominy while still on the lam.

Wilson, Rutledge, and Jay were Washington’s finalists for the position of chief justice. Each of them had a remarkable career before, during, and after the Revolution, and each experienced exceptional success as a lawyer. Yet Wilson and Rutledge’s fates sadly diverged substantially from Jay’s later in life.

The first three appointees to the Supreme Court all shared the advantages of being born into wealthy and influential colonial families, and all were given several legs up in their rise to prominence. Wilson had no such advantages. Born in 1742 in Fifeshire, Scotland, Wilson was the eldest of seven children of a hard-working but relatively poor farmer. Wilson’s family was Calvinist, and his parents desperately wanted him to become a “minister of the Kirk.” Ministers needed to be educated, so when Wilson turned 14 he earned a bursary scholarship to St Andrews, and his parents scraped together the remainder of the support from their meager earnings on the farm. He studied mathematics, Latin, Greek, and philosophy for five years in Scottish universities before Wilson’s father died.

At this point Wilson was forced to quit his studies and help support his widowed mother and siblings. He left the university, abandoned the ministry, and worked for a period as a private tutor. Once his brothers and the farm became more self-supporting, Wilson moved to Edinburgh to briefly study accounting before deciding that Scotland severely limited the prospects of an ambitious and brilliant young man. He set sail for America in 1765.

Wilson headed to Philadelphia and became a tutor at the College of Philadelphia (now the University of Pennsylvania), an academic home that he would return to later in life. But Wilson had not moved to America to reprise his role as a lowly tutor, so in 1766 he found a position as an apprentice to read the law with John Dickinson, a prominent Philadelphia attorney. Dickinson was one of the leading lawyers in Philadelphia and had himself studied at the London Inns of Court. Wilson served in this role for just two years and was a member of the bar of Pennsylvania by 1767.

Here we see the first signs of Wilson’s spectacular abilities as a legal mind, but also as a self-promoter. As the stories of Jay, Rutledge, and Cushing well establish, a good apprenticeship was the 18th-century version of a Harvard Law degree—it launched young lawyers into their careers. They were thus almost as difficult to obtain as a modern Harvard Law degree, especially for a brash Scotsman with no particular family connections or wealth. Wilson’s ability to garner this apprenticeship alone shows a remarkable talent.

Terms as an apprentice were also expensive, so Wilson borrowed the fees from his cousin Robert Annan. Debt, sadly, was to become a theme of Wilson’s life. Note also the differences in the period of study. Jay and Cushing each read the law for four years and Rutledge spent three years at Middle Temple after a few years of reading the law with his uncle. Wilson was done in under two.

Wilson’s background in political philosophy and his time studying at St. Andrews during the period known as the Scottish Enlightenment led him naturally to involving himself with the intellectual movements underpinning the bubbling American Revolution. In 1774, two years before the Declaration of Independence, Wilson wrote the highly influential Considerations on the Nature and Extent of the Legislative Authority of the British Parliament. Wilson was one of the first and most prominent American voices arguing that the British Parliament had no authority over the colonies because the colonists had no role in selecting representatives. This was a radical argument at the time, and Wilson was well ahead of the curve in making it forcefully and explicitly. This, too, was a theme of Wilson’s life.

In 1774, Wilson’s prominence led to his selection to represent Pennsylvania in the Continental Congress. He signed the Declaration of Independence and served in the Continental Congress off and on until becoming a Pennsylvania delegate to the Constitutional Convention in 1787. While less celebrated than Hamilton or Madison, Wilson is widely seen as one of the prime architects of our Constitution. He was the primary drafter in the all-important Committee of Detail, which hammered out many critical compromises.

Wilson held a unique assortment of different political positions at the Convention. He argued for a powerful central government, so he aligned with the Federalists in some ways, but also for more direct democratic control, so sometimes in line with the Antifederalists. He argued for direct election of the president and the Senate, views well ahead of his time on those structural issues. Moreover, Wilson is one of the earliest proponents of the general principle of “one man, one vote.” Of all the founders, Wilson may be the one whose views most closely track with the country we eventually became. Wilson then helped persuade Pennsylvania to ratify the new Constitution and helped draft the Pennsylvania Constitution of 1790.

Wilson also became the first professor of law at the College of Philadelphia and promptly began working on a magnum opus explaining the role of the common law in the new American constitutional scheme. Wilson sought to draw an explicit distinction between Sir William Blackstone’s vision of law as a rule prescribed by a superior and the new American conception of law’s legitimacy arising from “the consent of those whose obedience the law requires.” This was an extremely controversial position at the time, but one in line with Wilson’s long-held belief that the power of the government came from the consent of the people, not from a higher authority.

Wilson was never satisfied to be just a professor or a politician or a successful lawyer; he also continuously sought great wealth. In the 18th century, as today, it was possible to make a very good living as a lawyer working for fees, but much harder to gain generational wealth. In that pursuit he engaged in land and business speculation from his earliest days, sometimes at a breakneck and reckless speed. He bought and sold lots of land. He operated an ironworks. He borrowed heavily in all of these endeavors.

Wilson proposed himself to Washington as the first chief justice but had to settle for a position as an associate justice. He served until 1798, and his work on the Court shows little of his visionary legal mind. During his tenure, the Court was still a rather minor force in national affairs, and Wilson decided relatively few weighty cases.

Wilson’s rapidly deteriorating finances also likely distracted him from his judicial duties. Before and immediately after the Revolution, American land speculators assumed that a continuing flood of European immigration would make frontier land ever more valuable, so there was a wild rush to purchase as much as possible. John Marshall bought his large holdings in the Northern Neck of Virginia in this same period. When the flood of immigration slowed to a trickle and the post-war economy slumped, the party came to an abrupt and unfortunate end, and Wilson struggled to stay ahead of his creditors.

It seems unbelievable today, but Wilson was pursued by creditors while riding circuit as a Supreme Court justice for months, one step ahead of debtor’s prison at each stop until they finally caught up with him and threw him into debtor’s prison in Burlington, New Jersey. Wilson’s eldest son bailed him out and Wilson fled to Edenton, North Carolina, the hometown of his fellow justice, James Iredell. Here yet another creditor, the former South Carolina Senator Pierce Butler (and his fellow member of the Constitutional Convention) chased Wilson down and jailed him again. Wilson’s son bailed him out again, and Wilson died soon thereafter of malaria, sweltering in the North Carolina summer heat. At the time of his death Wilson owed Butler $197,000, an unimaginably large sum in 1798. And Butler was hardly Wilson’s only creditor.

Wilson is thus a quintessential modern American character. Like Alexander Hamilton, he was a first-generation immigrant who made it big in America solely due to his intellect and work ethic. He was also a political philosopher of remarkable prescience, forcefully arguing for a democratic vision of America that would triumph long after his death. He is also one of those founders that makes you wonder how it was possible to be engaged in so many different undertakings, as a leading voice in drafting the Constitution, a brilliant professor of law, a decorated politician, a world class lawyer, and an active (if ultimately unsuccessful) businessman. Robert McCloskey’s write-up on Wilson in The Justices of the United States Supreme Court wraps up a uniquely American life quite nicely:

[Wilson] had many of the qualities we might look for in a great constitutional statesman-judge: learning, industry, insight, all far beyond the common measure. If he lacked some of the others that a man like Marshall had, those deficiencies might have been overcome, in the right time and place, by the sheer force of his abilities. But he wanted too many things, and he seemed congenitally unable to choose between them. He wanted to be, not a freebooting financier, or a politician, or a revered constitutional statesman, but all three. This may be too much for any man to ask at any time. It was certainly too much for a man like Wilson.

Wilson went from having a key role in the drafting of our Constitution and an inaugural seat on the Supreme Court to a Death of a Salesman–esque final chapter, dying penniless in North Carolina. He was buried on James Iredell’s plantation because his family could not afford to have the body returned to Philadelphia. He now survives as a footnote in American history.

John Blair, Jr.

Blair was born into one of the leading political families in Virginia in 1732. His father, John Blair, Sr., served colonial Virginia in the House of Burgesses, as a member of the Governor’s Council, and as acting governor in 1758. Blair’s great uncle, James Blair, founded William and Mary College in 1693 and served as “president for life” of the institution for 50 years until 1743.

Blair came from a family of wealthy land and slave owners and was thus afforded an exceptional education. He graduated from William and Mary with honors in 1754 and studied law at the Middle Temple in London from 1755 to 1756. (Again, note how wealthy plantation owners were in the pre-Revolution Southern colonies. John Jay’s New York City merchant father could not afford to send him to London, but Rutledge and Blair’s slave plantation-supported families could.)

After completing his studies abroad, Blair returned to Williamsburg and became a well-known and well-compensated member of the bar. Blair is unusual among early Supreme Court justices in that he joined the bar immediately upon returning from the Middle Temple rather than serving in an American apprenticeship. This likely reflects the extraordinary credit given to a Middle Temple education.

Blair was a member of the illustrious Virginia Delegation to the Constitutional Convention of 1787 along with George Washington, Edmund Randolph, James Madison, and George Mason. Madison and Robert Yates’ notes on the convention suggest that Blair never gave a speech at the convention; it would be hard not to be overshadowed by his fellow Virginians. In this way Blair resembles Cushing—he was a B-list lawyer (relatively speaking) from a state filled with true legal giants. He was also primarily a former judge by the time he was appointed. As with Cushing, it is harsh to condemn Blair as a mediocrity. He was chosen to represent Virginia—the wealthiest and most populous state in the union and the home to many of the most decorated lawyers and leaders in the country—at the Constitutional Convention, so he surely was respected by his peers.

Blair signed the Constitution on behalf of Virginia and likewise advocated for Virginia’s adoption of the Constitution in 1788. Blair was Washington’s fifth nominee to the Court, and he joined Jay and his fellow justices in New York City (then the U.S. Capital) in February 1790 for the Court’s first sitting. He served until his resignation for health reasons in 1796.

James Iredell

James Iredell was born October 5, 1751, in Lewes, England. His father was a prosperous merchant in Bristol until he fell ill at some point during the 1760s. The illness debilitated his father’s health and business. The situation grew dire enough that in 1768, at 17 years old, James Iredell sailed for Edenton, North Carolina, to become Comptroller of His Majesty’s Customs. The position was purchased by a cousin, and the £30 salary was to be paid directly to Iredell’s father. Iredell was to earn roughly £100 a year on “fees.”

The job did not turn out to be the easy sinecure that Iredell’s family expected. The bulk of Iredell’s income came from customs fees, which had recently proven extremely controversial. The Stamp Act was a particular flashpoint. In January 1766, the North Carolina Sons of Liberty burned in effigy the customs agent in Cape Fear, North Carolina, and by February over 1,000 armed and rowdy dissidents forced the reopening of the port and ended Stamp Act collections. The Stamp Act was repealed later that year, but the atmosphere was hardly conducive to friendly relations between the Crown’s customs agents (like Iredell) and the people of North Carolina.

Iredell was an ambitious young man, and soon after arriving in Edenton he began an apprenticeship with a leading local lawyer, Samuel Johnston. Johnston would later serve as North Carolina’s governor and U.S. senator, and was among the leading lights of North Carolina’s bar. Iredell studied hard under Johnston, hard enough that in his contemporary diary he reprimands himself for the “indolence” of taking a break from studying Lyttleton’s Tenures on Rents to lose “three or four games at billiards.” Contemporary law students will surely recognize this struggle.

Iredell was a quick study and he joined the Bar of North Carolina in 1770 and began to build a successful legal practice. Like his contemporaries he took all sorts of legal work, including admiralty suits, land disputes, will drafting, and much more. He was successful enough that he described himself as “beset with clients” and at one point stopped taking new business.

As the Revolution dawned, Iredell’s relatives in England were concerned about young James’ fading loyalty to the Crown. In 1775, his uncle wrote, “I am concerned to find you so full of politics . . . they can be of no use to you as a King’s officer. . . . The people of America are certainly mad.” Notwithstanding these exhortations, Iredell chose his new home over the old and became an influential political writer in North Carolina in support of the Revolutionary cause.

After North Carolina became independent in 1776, Iredell took a leading role in drafting and revising the existing statutes to reflect the new state constitution. He then served a year as one of three Superior Court Judges in the state, holding one of North Carolina’s highest judicial offices at the age of twenty-seven. Circuit riding in North Carolina proved too taxing, and Iredell returned to practice and then to serve as North Carolina’s attorney general from 1779 to 1781. As the state’s primary prosecutor, he tried criminal cases all over the state. In 1781, he again returned to his profitable law practice.

Iredell in 1788 turned to advocating the ratification of the new U.S. Constitution. He gave a leading speech during the 1788 convention. The initial vote for ratification was unsuccessful (North Carolina did not ratify until 1789), but Iredell’s efforts were sufficient to draw national attention. In 1790, when Robert Harrison of Maryland declined to join the Court for health reasons, Washington appointed Iredell. Iredell was thus one of the first six justices on the Court, but not among the first six nominees. In his diary, Washington praised Iredell’s “abilities, legal knowledge, and respectability of character,” and noted that “he is of a State of some importance in the Union that has given no character to a federal office.”

The Original Supreme Court

We now have the original Supreme Court. The Court met for the first time in February 1790 with just five confirmed justices: Jay, Rutledge, Cushing, Wilson, and Blair. The Court’s second sitting, in August 1790, included Iredell, so every seat was finally filled. Rutledge was absent from both of the first two sittings, and both times the Court convened and then almost immediately adjourned for lack of business. For the first few years the bulk of their actual work was done while riding circuit.

Washington’s first justices were a diverse and accomplished group of lawyers. They reflected the best from the colonies. Each had fought hard for independence and again in support of the new Constitution. Washington probably hoped he was finished dealing with the Court in 1790, but he had no such luck.