Just as the investigation into the “terror attack” of January 6 was in full swing in the autumn of 2021, court proceedings in the alleged 2020 plot to kidnap of Governor Gretchen Whitmer began in Michigan.

When 13 men allegedly tied to militia groups were arrested on October 7 of this year on federal and state charges for planning to kidnap Whitmer from her Michigan vacation cottage, Team Biden and Whitmer herself made the most of the timely political gift. “There is a through line from President Trump’s dog whistles and tolerance of hate, vengeance, and lawlessness to plots such as this one,” Biden said in an October 9 statement. “He is giving oxygen to the bigotry and hate we see on the march in our country.”

In a press release announcing the arrest of six of the plotters on federal charges, the Justice Department detailed the elaborate plan. “This group used operational security measures, including communicating by encrypted messaging platforms. On two occasions, members of the alleged conspiracy conducted coordinated surveillance on the Governor’s vacation home . . . and discussed detonating explosive devices to divert police.” The wannabe kidnappers planned to use a taser gun on Whitmer then either abandon her in a boat on a nearby lake or transport her to Wisconsin to stand trial. “These alleged extremists undertook a plot to kidnap a sitting governor,” the assistant FBI special agent in charge said in the statement. “Whenever extremists move into the realm of actually planning violent acts, the FBI Joint Terrorism Task Force stands ready to identify, disrupt, and dismantle their operations, preventing them from following through on those plans.”

Investigating—or Planning—the Plot?

But the Justice Department’s description failed to match reality as court documents and testimony would show. Far from the FBI thwarting the operation, the FBI itself enlisted participants, organized and funded training and surveillance trips, and used paid informants working with FBI agents to lure unsuspecting “militia” members into attempting to execute the plot.

The scheme centered around a group called the Wolverine Watchmen, an unknown “militia” group formed online in late 2019 by another man who faced state, not federal, charges related to the plot. (The man, Joseph Morrison, created a Facebook page for the new group four days after he was arrested on a weapons charge, which was pleaded down to a misdemeanor with time served—one day in jail.) It was essentially a small online group of malcontents, more smoke than fire.

An extensive exposé published in July 2021 by BuzzFeed News detailed how the plot went down and the close involvement of at least twelve FBI agents and informants. Contradicting the government’s early claims, the site’s investigative reporters concluded the following: “An examination of the case by BuzzFeed News also reveals that some of those informants, acting under the direction of the FBI, played a far larger role than has previously been reported,” Ken Bensinger and Jessica Garrison wrote on July 20. “Working in secret, they did more than just passively observe and report on the actions of the suspects. Instead, they had a hand in nearly every aspect of the alleged plot, starting with its inception. The extent of their involvement raises questions as to whether there would have even been a conspiracy without them.”

The insurrectionary plot had the government’s fingerprints all over it. Every man involved in the kidnapping scheme had an FBI handler. According to a filing by one defense lawyer, “the government has shared ID numbers linked to 12 confidential informants but, with one exception, has not provided background on how they were recruited, what payments they may have received from the FBI, where they are based, or what their names are.” The lead informant, known as “Big Dan,” was paid at least $54,000 by the FBI for seven months of work, a sum that included reimbursing him for a loss when he sold his home out of fear his identity would be revealed.

Special agent Jayson Chambers, while working the Whitmer case, also coaxed “Big Dan” to enlist another man in Virginia to concoct a plot to kill Virginia Governor Ralph Northam. Chambers made clear to “Big Dan” what he was supposed to convince “Frank,” his target, a disabled Vietnam veteran, to do. “The mission is to kill the governor specifically,” Chambers texted. He further instructed “Big Dan” to tell “Frank” how to build an explosive device, an approach similar to the one used in the Whitmer scheme.

The FBI’s Troublesome History with “Domestic Enemies”

During the Trump era, Democrats and Republicans abandoned their traditional positions on federal law enforcement. The Republican Party that embraced the Patriot Act and generally trusted the agency to work within legal and constitutional constraints now viewed the FBI as a crucial part of the “Deep State,” a hostile agent loyal to the Democratic Party. Democrats and progressives who historically viewed the FBI as a rights-crushing, racist Gestapo suddenly canonized people like former FBI deputy director Andrew McCabe.

One fact was not up for dispute, however; the agency has a long history of meddling in domestic political affairs starting with J. Edgar Hoover, the FBI director whose name is emblazoned on FBI headquarters in Washington. Hoover authored a memo in 1956 that called for the agency to track Americans he perceived as enemies of the state. The new program, COINTELPRO, launched that year to surveil suspected members of the Communist Party in the United States. Gradually, other groups—the Ku Klux Klan, the Black Panther Party, Puerto Rican nationalists, and the Socialist Worker’s Party—were added to COINTELPRO’s target list.

Some of the abuses ended after the Church Commission, a Senate select committee tasked with investigating COINTELPRO, accused the FBI of acting unlawfully. “What happened to turn a law enforcement agency into a law violator? Why do those involved still believe their actions were not only defensible, but right?” the committee’s final report asked.

In the early 1990s, the FBI accelerated its focus on the white Christian Right. After the events at Waco, Texas, and Ruby Ridge, the FBI launched PATCON, short for Patriot Conspiracy, an alleged movement of Christian extremists. In one case, the FBI created a fictional right-wing militia group to collect information about other suspected militia members. A 2011 study done by Rutgers University raised serious concerns: “The tactics of FBI agents infiltrating militias, as well as paid informants being coerced into spying on these groups, and, in some instances, even providing the means and encouragement to carry out violent plots before being arrested, have been criticized as constituting entrapment by using agent provocateurs—agents posing as criminals to justify the financial and social expenses of counter-terrorism.”

Was this the case with January 6?

Independent Journalists Uncovering the Truth

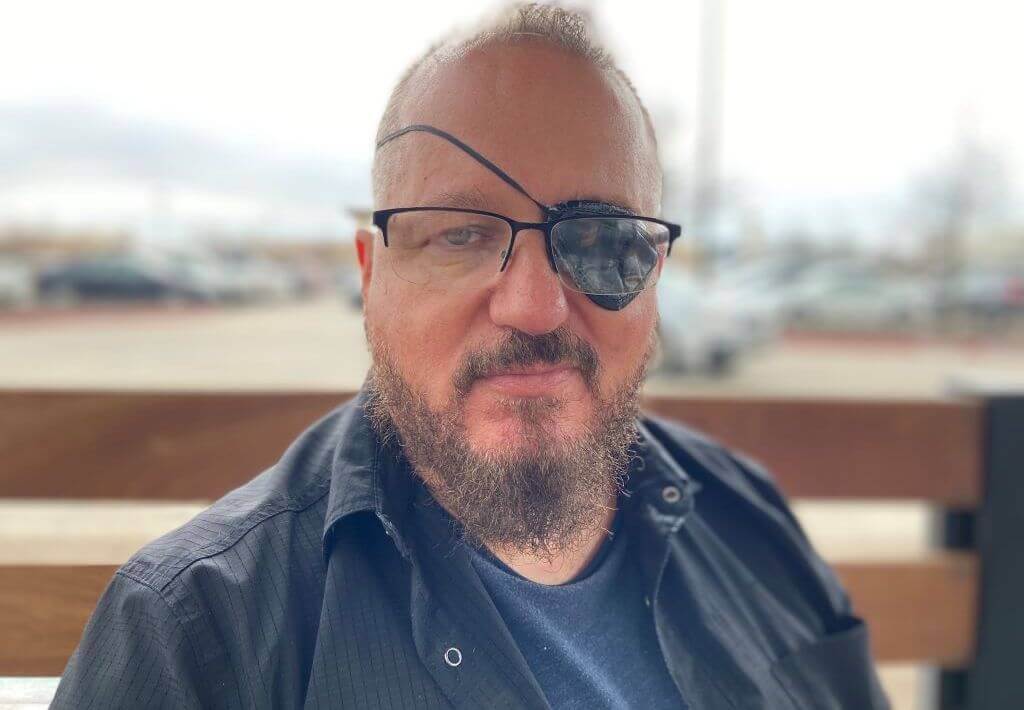

A small handful of journalists resisting the groupthink of January 6 have raised several red flags. In June, Revolver News, a new website founded by Darren Beattie, a former aide to Donald Trump, published a lengthy report raising questions about the number of unindicted co-conspirators in the Oath Keepers case, including Stewart Rhodes. Rhodes is widely accepted as “Person One” in the multi-defendant case. Communications between Rhodes and other Oath Keepers conspirators were cited as evidence in every case; it was obvious he was calling the shots.

But nine months after the first arrests, he was still a free man.

“Given . . . Stewart Rhodes’s actions and words leading up to and on 1/6, and given that Rhodes is the leader of the major militia group associated with 1/6—why no indictment for Rhodes?” Beattie asked. Citing similarities to the Whitmer case, Beattie continued,

If it turns out that an extraordinary percentage of the members of these groups involved in planning and executing the Capitol Siege were federal informants or undercover operatives, the implications would be nothing short of staggering. This would be far worse than the already bad situation of the government knowing about the possibility of violence and doing nothing. Instead, this would imply that elements of the federal government were active instigators in the most egregious and spectacular aspects of 1/6, amounting to a monumental entrapment scheme used as a pretext to imprison otherwise harmless protestors at the Capitol—and in a much larger sense used to frame the entire MAGA movement as potential domestic terrorists.

Given the FBI’s long history of using false-front groups as flypaper to attract dangerous radicals, and then moving them to commit actionable crimes, this kind of speculation seems far from unreasonable.

Beattie’s reporting went viral, earning spots on “Tucker Carlson Tonight” but scorn by the establishment media and those invested in the January 6 “insurrection” narrative. Rhodes then gave an interview, which seemed more like damage control, to the New York Times that revealed he had been interviewed by the FBI in May. “Against the advice of a lawyer, Mr. Rhodes spoke freely with the agents about the Capitol assault for nearly three hours,” reporter Alan Feuer wrote in a July 9 article. Rhodes told Feuer that his underlings had “gone off mission” and that he was “frustrated” so many entered the building. “Prosecutors overseeing the investigation of Mr. Rhodes have long admitted that they have struggled to make a case against him. His activities seemed to stay within the boundaries of the First Amendment, one official with knowledge of the matter said.”

But Rhodes’ posts and texts before January 6 were highly inflammatory and contradicted his portrayal in the Times. Further, the argument that his online activity and his conduct that day were protected by the First Amendment also contradicted the government’s stance that the events of January 6 rose to the crime of insurrection, not a legitimate political protest. Rhodes did not enter the Capitol building, but neither did dozens of other protesters nonetheless charged with various crimes. Thomas Caldwell, for example, one of the first Oath Keepers arrested and indicted, also did not enter the building.

Beattie followed up his initial reports with an updated piece in October that summarized the Justice Department’s nine-month prosecution of the Oath Keepers. Rhodes, Beattie explained, established the conspiracy, recruited the people involved, gave instructions including the use of illegal weapons, and activated the conspiracy, including the entrance into the building in a stack formation, that afternoon. Still, Rhodes remained uncharged.

So did a man named Ray Epps. In another bombshell at Revolver, Beattie noted that despite egging on protesters on both January 5 and 6, the government had not charged Epps with any offense. He is clearly seen on at least three occasions encouraging people to storm the Capitol. During a confrontation between Trump supporters and BLM/Antifa activists at Black Lives Matter Plaza across from the White House late on January 5, Epps told Trump supporters what they need to do the next day. “We need to go in to the Capitol,” Epps, wearing a Trump hat, yelled, pointing east toward the building. “Peacefully!”

Some people smelled a rat. They loudly shouted “no” in response and a few started chanting “Fed! Fed! Fed!”

For 90 minutes, Epps, who looks and sounds every bit the aging Marine sergeant that he is, tried to convince people to head to the Capitol on January 5. The next day, Epps is at it again. Shortly after Trump began his speech around noon, Epps is seen hollering at passersby, “After the speech, we are going to the Capitol. Where our problems are!” A half-hour later, Epps whispered into the ear of Ryan Samsel just seconds before Samsel charged up the steps and became the first to breach the police line on the west side of the Capitol.

As it turns out, Epps is more than a retired Marine who loves his country. He also is the former head of the Arizona chapter of the Oath Keepers, the group still run by Stewart Rhodes. They are photographed together at various events in 2011.

Beattie also noted that after landing on the FBI’s most wanted Capitol protesters roster as early as January 8, Epps’ photo was quietly scrubbed from the list in July.

But despite overwhelming evidence that Epps repeatedly attempted to incite the crowd over an 18-hour period, by November 1 he still had not been arrested. How could a man on the FBI’s most-wanted list for six months, then suspiciously removed, remain scot-free while others accused of mere trespassing were hunted down by the FBI?

A few days after Beattie’s piece was posted, Attorney General Merrick Garland testified before the House Judiciary Committee. Representative Tom Massie (R-Ky.) played a video montage of Epps’ clips from January 5 and 6 and challenged Garland to explain them.

Massie: You said this is one of the most sweeping [investigations] in history. Have you seen that video, or those frames from that video?

Garland: So as I said at the outset, one of the norms of the Justice Department is to not comment on pending investigations, and particularly not to comment on particular scenes or particular individuals.

Massie: I was hoping today to give you an opportunity to put to rest the concerns that people have that there were federal agents or assets of the federal government present on January 5 and January 6. Can you tell us, without talking about particular incidents or particular videos, how many agents or assets of the federal government were present on January 6, whether they agitated to go into the Capitol, and if any of them did?

Garland: So I’m not going to violate this norm of, of, of, the rule of law.

Inconsistencies are also appearing in the prosecution of the Proud Boys. Enrique Tarrio, the head of the group, was arrested on January 4 in Washington on an outstanding warrant for burning a Black Lives Matter flag during a counterprotest in December 2020. Tarrio also had two high-capacity firearm magazines in his car at the time of his arrest.

As part of his release, Tarrio was ordered to leave the city; he could not attend the protest on January 6. Yet Tarrio, up until that point, had led most of the pre-planning discussions about what the Proud Boys would do on January 6. The fact he wasn’t actually in the city that day doesn’t override the fact he was intimately involved beforehand. As with Rhodes, any “conspiracy” to “attack” the Capitol came at the direction of Tarrio.

The timing of his arrest, which prevented him from joining a large group of Proud Boys on January 6, and the fact he had not been named in any Proud Boy indictment led to speculation he might be working with the feds.

After all, he had done so before. A January 2021 report by Reuters revealed that Tarrio had a history as a government informant. “A Federal Bureau of Investigation agent and Tarrio’s own lawyer described his undercover work and said he had helped authorities prosecute more than a dozen people in various cases involving drugs, gambling and human smuggling,” Aram Roston disclosed in the January 27 article. “The records uncovered by Reuters are startling because they show that a leader of a far-right group now under intense scrutiny by law enforcement was previously an active collaborator with criminal investigators.” Tarrio’s cooperation with the government came after he was charged in 2012 for fraud.

When asked for comment, Tarrio told Roston he didn’t “recall any of this.”

Then came a bombshell from the New York Times: the group of Proud Boys in the capital on January 6 included at least two federal informants who were in constant communication with their FBI handlers. “The informant, who started working with the F.B.I. in July 2020, appears to have been close to several other members of his Proud Boys chapter, including some who have been charged in the attack,” Alan Feuer wrote on September 25. The Times had received access to confidential records documenting the informants’ activities. “The F.B.I. also had an additional informant with ties to another Proud Boys chapter that took part in the sacking of the Capitol.”

Aside from the revelation about FBI informants within the Proud Boys during the Capitol protest, Feuer also suggested that the information did not prove the Proud Boys conspired to “stop, delay, or hinder Congress’ certification of the Electoral College vote,” as the government alleged in indictments. The informant, according to the documents Feuer viewed, repeatedly said the Proud Boys’ plan was to maintain a defensive posture and prepare to fight leftist agitators such as Antifa.

A few weeks later, Feuer followed up with an article over a dispute between Joe Biggs, the Proud Boys leader on the ground that day, and Ryan Samsel, one of the first protesters to knock down barriers around 1:00 p.m. on January 6. Video shows the two briefly speaking before Samsel confronted Capitol police stationed in front of a slim row of metal racks. Samsel told investigators, according to Feuer, that Biggs urged him to breach the line. “[W]hen he hesitated, the Proud Boys leader flashed a gun, questioned his manhood and repeated his demand to move upfront and challenge the police.”

Biggs’ attorney denied Samsel’s account, telling Feuer that Biggs was not armed on January 6. But the account added a new wrinkle to what may have transpired in the moments before the group of Proud Boys first overran barriers and law enforcement.

Biggs also had a relationship with the FBI. He turned himself in to two agents, including “one he’d known for a long time,” according to his lawyer, on January 20. In a court filing, Biggs’ lawyers described how his client routinely met and spoke with the FBI, including agents at the Portland FBI field office, about his plans to organize Proud Boys rallies in that city as a counterdemonstration to Antifa protests. In 2018, FBI agents in Florida, where Biggs lives, started questioning “what Biggs meant by something politically or culturally provocative he had said on the air or on social media concerning a national issue, political parties, the Proud Boys, Antifa or other groups,” his lawyer wrote.

Instilling Fear

The FBI’s nationwide manhunt to round up January 6 protesters was a show of force usually reserved for the country’s most dangerous criminals. Agents were let loose to capture hundreds of Capitol protesters in their own homes or their place of work. Families were awakened at dawn by armed officers screaming commands, children were terrified, neighbors were horrified. The over-the-top displays were intended to inflict maximum fear and humiliation. The stories were something straight out of a totalitarian nightmare.

“Mommy, why are they locking Daddy’s hands?”

The little girl heard asking the question on a home security video is the daughter of Casey Cusick, the vice president of Global Outreach Ministries in Melbourne, Florida. Cusick and his father, James, the founder of the church, were arrested on the same day for entering the Capitol on January 6.

FBI agents went to Casey Cusick’s home on June 24 with an arrest and search warrant; the officers, with guns drawn, asked the family to exit the home so they could “clear this residence.” Casey’s wife, carrying a toddler on her hip and holding the hand of her three-year-old daughter, asks repeatedly to see the warrant but officers ignore her.

About 15 minutes away, Casey’s father, a 73-year-old pastor, Vietnam War veteran, and Purple Heart recipient, was handcuffed in front of his adult daughter, Staci, and their neighbors. “[T]here’s just no reason for it. He did nothing to deserve what we saw this morning,” Staci later told a reporter for the Gateway Pundit. “I don’t understand why they would feel okay doing this to someone like him. I think they felt bad about it, but they kept saying it’s their job.” Agents confiscated the clothes he wore to the protest on January 6.

So what crime did the Cusicks commit that required such a show of force, a display that traumatized their family including young children? The same four misdemeanors charged in the overwhelming majority of Capitol breach cases: Entering and Remaining in a Restricted Building, Disorderly and Disruptive Conduct in a Restricted Building, Violent Entry and Disorderly Conduct in a Capitol Building, and Parading, Demonstrating, or Picketing in a Capitol Building.

What happened to the Cusicks happened all over the country for months as the FBI executed raids of people’s homes, even those charged with low-level offenses. The purpose is clear: to humiliate the accused in front of their neighbors and give fodder to local news reporters who can breathlessly tell their viewers that an “insurrectionist” lives among them.

FBI Director Chris Wray boasts during congressional hearings that every one of the FBI’s 56 field offices is involved in the Capitol breach probe. From Alaska to New York, homes have been ransacked and reputations crushed. The accused were often interrogated for hours without a lawyer present and before a warrant was shown.

Since mid-January, the FBI’s Joint Terrorism Task Force has conducted excessive raids related to the Capitol breach probe, creating their own campaign of terror in the process.

Coincidentally—or perhaps not—Steven D’Antuono, the FBI brass whom Wray moved from the Detroit field office to Washington, D.C. just a few weeks before the election, promised a scorched earth approach. “Just because you’ve left the D.C. region, you can still expect a knock on the door if we find out that you were part of criminal activity inside the Capitol. Bottom line—the FBI is not sparing any resources in this investigation,” D’Antuono said in a January 8 statement.

He wasn’t kidding.

In one instance, residents in a Cape Coral, Florida neighborhood watched in the early morning hours of March 12 as the FBI barricaded their street in preparation to search the home of Christopher Worrell, an alleged member of the Proud Boys. A Fort Myers television station reported that the raid involved “armed men with helmets and a tanker truck.” One neighbor confirmed the agents broke down the front door of Worrell’s modest home where he lives with his girlfriend. “This was a little too much when you see FBI and SWAT teams. They were taking duffel bags out,” Lynn Elias told a reporter for WINK-TV.

Agents were wearing “whole outfits like [the] military” and arrived in “six or seven . . . big black vehicles.” Worrell, however, was not home. His girlfriend connected agents with Worrell by phone. The FBI instructed Worrell to turn himself in at the Sarasota field office; Worrell refused, drove back home, and was arrested later that day. He was indicted in April on several counts including using pepper spray against law enforcement. Worrell never entered the Capitol building on January 6; he was ordered detained and transferred to the D.C. jail.

In another Florida raid a few months later, a neighbor of Olivia and Jonathan Pollock, siblings accused of assaulting police on January 6, told a local reporter he “grabbed his gun” around 5:30 a.m. on June 30 when he heard the sounds of explosive devices outside his home. The FBI had surrounded the Pollocks’ rural property in Lakeland to execute a search warrant and, according to video taken by the neighbor, agents used flashbangs and bullhorns to instruct the Pollocks to “come out with your hands up.” An elderly relative of the Pollocks told Tampa reporter Staci DaSilva that she was so shaken by the hours-long raid “she could hardly talk.”

The FBI and Big Tech Join Forces

The FBI’s shocking behavior isn’t just related to intrusive, putative raids at the homes of trespassers or even innocent Trump supporters. Investigators, in search of a crime, swept up personal information off electronic devices using surveillance tools designed to track legitimate terrorist threats.

Cellular providers have been eager to help the government. It appears that not a single telecommunications company has put up a fight to protect their users’ privacy. Subpoenas to confirm cell phone numbers, email addresses, and other personal information linked to social media accounts have been fully complied with as far as court documents show.

“In the hours and days after the Capitol riot, the FBI relied in some cases on emergency orders that do not require court authorization in order to quickly secure actual communications from people who were identified at the crime scene,” an investigative report by The Intercept revealed in February. “Federal authorities have used the emergency orders in combination with signed court orders under the so-called pen/trap exception to the Stored Communications Act to try to determine who was present at the time that the Capitol was breached, the source said. In some cases, the Justice Department has used these and other ‘hybrid’ court orders to collect actual content from cell phones, like text messages and other communications, in building cases against the rioters.”

Members of Congress and congressional staff were part of the massive dragnet. So, too, were people who were in D.C. that day but did not participate in any of the events. Senator Mike Lee (R-Texas) confronted Christopher Wray on the issue during a March 2 hearing. Lee told Wray he had heard from numerous individuals who “never got near the Capitol or any violence on January 6 who have inexplicably been contacted by the FBI by agents who apparently were aware of their presence in Washington, D.C. that day. Are you geolocating people through the FBI?”

When Wray tap-danced around the question, Lee pressed forward, asking if the FBI used national security letters or the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, the secret court that had improperly authorized spying on Team Trump, to secure the geolocation data.

Wray told Lee he “does not believe” national security letters or FISA warrants were part of the collection process, but confirmed that warrants were issued to get the cell data “under the legal authority we have in consultation with the department and the prosecutors.”

Those warrants—Wray intentionally did not elaborate—were geofence warrants on Google, which has a much better way of tracking users than cell phone providers. An investigative report by Wired in September confirmed at least 45 January 6 criminal cases used evidence collected by a Google geofence warrant. One warrant was issued as the protest was underway on January 6.

“A geofence warrant initially seeks an anonymized list of devices tracked within a specific area at a specific time,” Wired reporter Mark Harris wrote on September 30. “Investigators then use that list to focus on tracks that look suspicious, and can ask Google to widen the time or geofence boundaries on only those devices. Finally, investigators can go back to Google to unmask the real name, email, phone number, and other information of just a few account holders. But where a typical geofence fishing expedition might catch only one or two suspects, the January 6 investigation appears to have landed a netful.”

Since the Justice Department had categorized the Capitol complex as a “crime scene” and Wray designated the four-hour event an act of “domestic terrorism,” private corporations from Verizon to Facebook presumably felt it was their duty to comply.

“The collection effort has been met with little resistance from telecom providers asked to turn over voluminous data on the activity that day. ‘No one wants to be on the wrong side of the insurrection,’ a source involved in the collection effort told The Intercept. ‘This is now the scene of the crime.’”