ARKANSAS — Clay Newcomb is on a personal mission to explore things forgotten in a digital world that moves past people and experiences at the speed of light. He revels in places, communities, traditions and lives that still remain deeply relevant to a lot of people and cultures across our country but risk being lost.

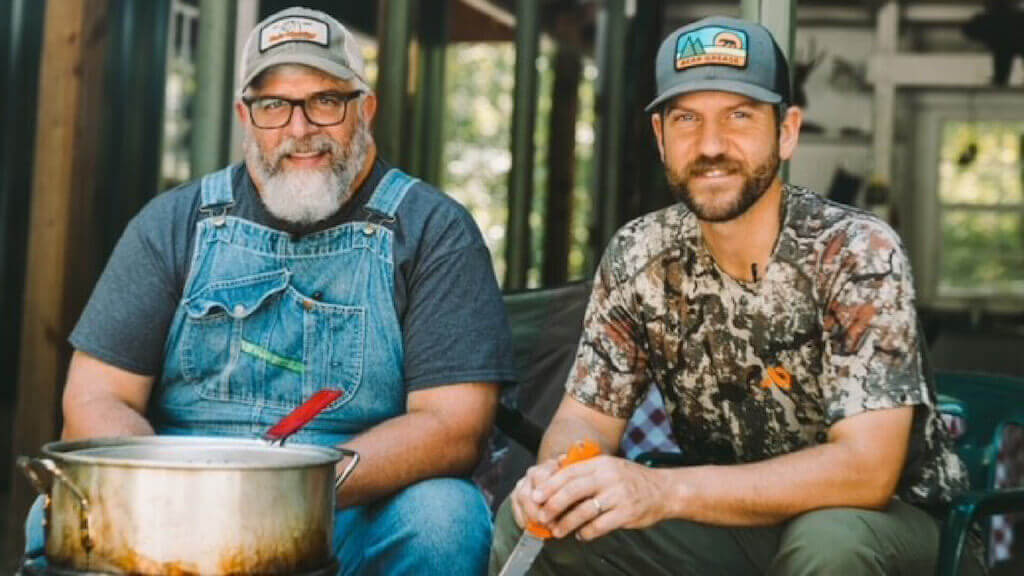

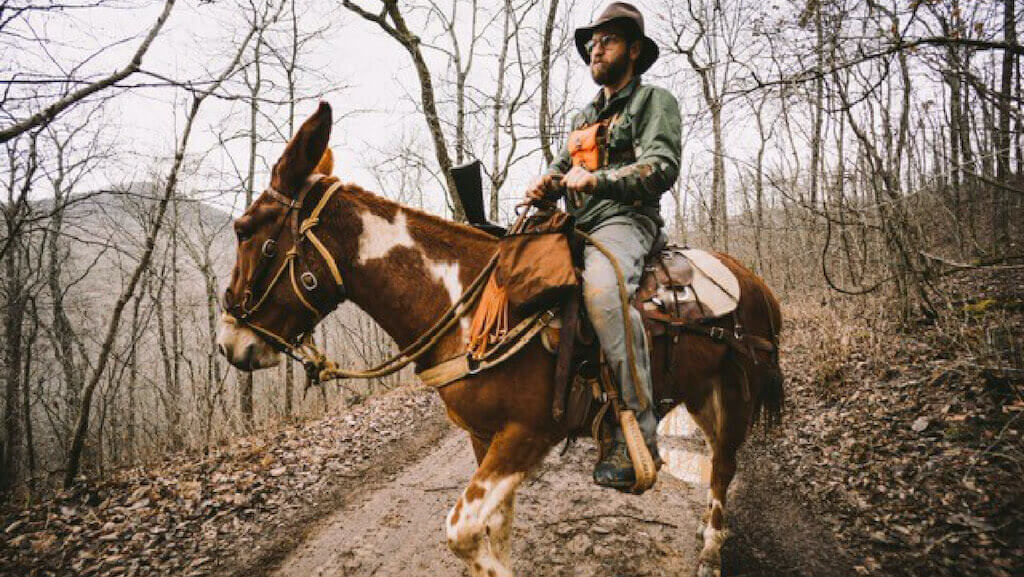

It was a mission he began long before he began producing his popular “Bear Grease” podcast, part of the iconic MeatEater podcast family. Newcomb, whose Instagram photos often show him sitting on a mule unironically, admits he never saw any of this coming.

“It has really been an interesting process to me as I’ve come into MeatEater, a process which has given me this massive platform that I’ve never thought I’d have,” he said. “I feel like I’m just doing all the stuff I’ve been doing my whole life. Only now, I have an audience.”

Newcomb is the embodiment of the American frontier, part Renaissance man, part mule wrangler, 100% storyteller. You cannot help but want to connect all at once with the land you occupy, the history that surrounds you that you never took the time to learn. What possibilities await, spending just one afternoon or one podcast with him and his cast of characters

“I’m a seventh-generation Arkansan,” he said. “My kids are eighth-generation. My family came here in the late 1820s and homesteaded in a community called Bumblebee in Montgomery County, Arkansas.”

It was not something his family had ever made much of. “I was the first person in our family that kind of declared that we were kind of explorers. Like, holy cow, we’ve been here since the late 1820s,” he said.

His grandfather was a Baptist pastor and bird-dog trainer in Montgomery County, Arkansas, and the first person ever to attend college in his family. “He was also a schoolteacher,” Newcomb said. “He was also a World War II veteran, and all those guys wanted their kids to go to college.”

And so they did; Newcomb said his father became a banker. “He was like a white-collar guy in our town. But he was also a hunter; as country as any of them.”

When his father came home from work, he didn’t tell stories about the insurance agents and the car dealers and the doctors that he worked with; he told them stories about the rural people.

“I spent my childhood hearing stories about the family that would come in and take out a $400 loan so that they could go catfishing for three weeks, the guys that were gathering moss for a living and selling moss,” he said. “He treated these people like they were kings.”

It was a dichotomy in the world that shaped who he is today. As he grew older, he realized that the people his father told him about were of no regard in a lot of places in society. “It was just like deep, deep inside of me that these were honorable people because my father saw them that way, and he was a good judge of character.”

Newcomb joined MeatEater in 2019; a prolific publisher, writer, cinematographer and photographer, he lives here with his wife and four children, the center of his universe.

He also owns, publishes and is the editor for Bear Hunting Magazine, the nation’s only all-bear-hunting publication. Outside his family, what drives him is introducing the connected world to his rooted world and showing them all that his world has to offer.

“What society values was not always what I valued, and until I worked for MeatEater, Salena, I just kind of assumed that I would live in terms of career and media as this lower-level outdoor media guy. And honestly, I was totally fine with that,” he said.

When he says that all he’s ever been interested in is keeping food on the table and raising his family in the way that he wants to, he means it.

“I’ve never wanted to have some big career or be well-known,” he said. “That was never the intent. And I felt like the stories that I was telling were of little value to anybody.”

He said he has also never been interested in elevating rural American culture to the point of saying that it is the best culture. “I think there’s deep value in valuing your own culture so that you can value the culture of others,” he said.

His podcast gives the uninformed a history lesson before they even listen to its first story. “Bear grease,” in case you are wondering, is the rendered fat of a bear, which is turned into a liquid oil that can be used for a multitude of things. At one time, it was the fuel of the American frontier.

The black bear, the second most widely distributed big game mammal in North America, had more tallow than any other animal. Before the modern convenience of widespread fossil fuels, animal oil was an essential component of survival for frontier families.

This meant that bears were a highly coveted resource.

Bear grease was used as a commodity, explained Newcomb. “It could be traded. It could be used like money. I like to say that it’s a wonder that we don’t call the American dollar ‘bear grease.’ We call it a buck instead. A buck was the tanned skin of a deer that was basically equivalent to the value of a dollar.” In the mid-1800s, you could have gone anywhere in this country and said the words “bear grease,” and people would have had a cultural reference point for what it was and its value.

Today, you’d hardly find anyone who knows what you’re referring to.

“Yet, that bear grease has not changed. It is still useful for all those things. It’s still healthy. It’s still available. It’s still something that a portion of the world still deeply values, and it’s been forgotten in our history books,” he said.

It wasn’t quite forgotten in my trip across the country. I came across dozens of people who knew exactly what bear grease was — a father in Indiana who was taking his son fishing, three young men working behind the counter at the Duluth Trading Post in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, even former Speaker of the House Paul Ryan from his home in Wisconsin. Why? Because they listen to the podcast.

“Bear Grease is a metaphor for things that have been forgotten but are still highly relevant,” Newcomb said, echoing the tagline of his podcast.

When Newcomb tells you he is exploring things forgotten but still relevant, it is not a line, but a lifestyle. And whether you are from a rural stretch in this country or live in the city, everyone learns something new when they listen to Newcomb.