All eyes are on Taiwan, and rightly so.

One of Churchill’s better sayings was when he observed that the Balkans was producing more history than it could ever hope to consume. That phrase came to mind when, in short order, Australia’s navy received the best present a naval enthusiast could hope for: nuclear submarines.

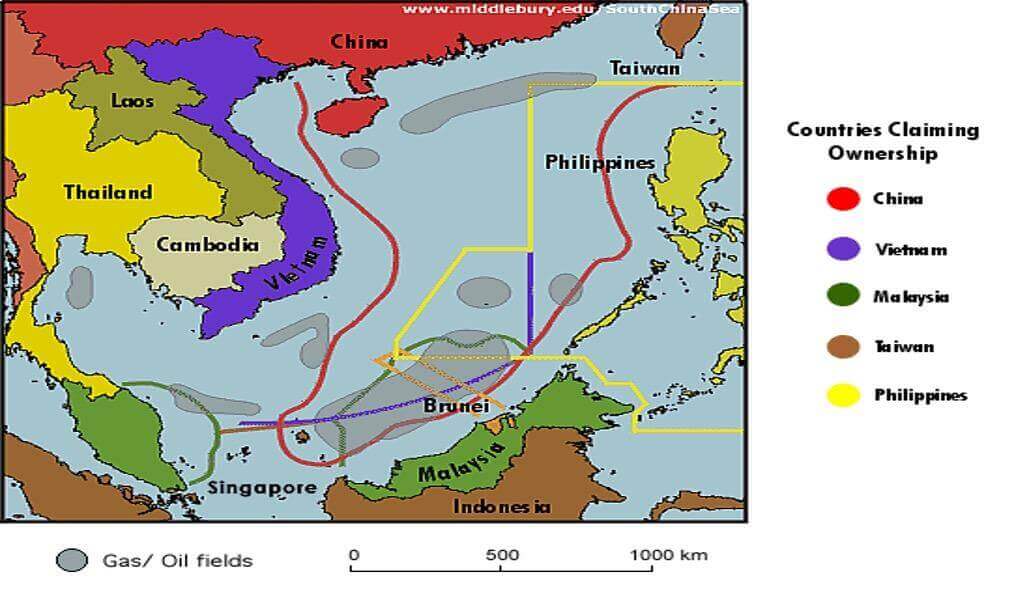

The map below is worth studying closely in this context. China’s maritime claims in the South China Sea (in red, commonly known as the Nine Dash line) reach a good 2000 km south of the continental shelf where the Chinese mainland becomes its territorial waters. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea grants China 12 nautical miles of territorial waters, the same as every other signatory that ratified it into national law. The 200 nautical miles (nm) of Exclusive Economic Zone also guaranteed by the treaty lets states claim landmasses within it—as well as the waters surrounding that landmass.

This includes, naturally, exclusive rights over hydrocarbon exploitation (oil and gas, to be clear). With 100 million proven barrels of oil and up to 160 billion barrels left to discover, as well as two trillion cubic feet of natural gas—running up to potentially 250 trillion cubic feet of natural gas—it is worth reminding the world that China has taken great pains to position itself favorably to control future exploitation of these fields, up to and including international litigation where Beijing outright lost the case yet remains in fraganti. Don’t forget that detail when you next hear about whichever climate target they pretend to agree to at COP.

And so it is by this collection of maritime claims—some outright fabricated through the creative gesture of entirely new landmasses—that China’s claim reaches all the way to our first teacup. Off the northern coasts of Brunei and Malaysia and the western coast of the Philippine island of Palawan you can find the Spratly Islands. Philippines v. China, (2013-19) the case whereby Manila established through international legal proceedings the legitimacy of its claim ultimately turned on a very fine distinction. As an archipelagic state, the Philippines’ chain of claims westward receives precedence in several crucial circumstances, over China’s lesser (in this case) status as a coastal state.

Our second teapot is the Paracel archipelago of islands, where our story can begin to take shape. Map enthusiasts can pause and go to an interactive spread of the area between Formosa—the island that contains the Taiwanese nation state—and Pratas island, a paradisiacal atoll 170 nm southwest. On this first claim rests the entire chain: concatenating through to the Scarborough Shoal and southwards to the Spratly Islands.

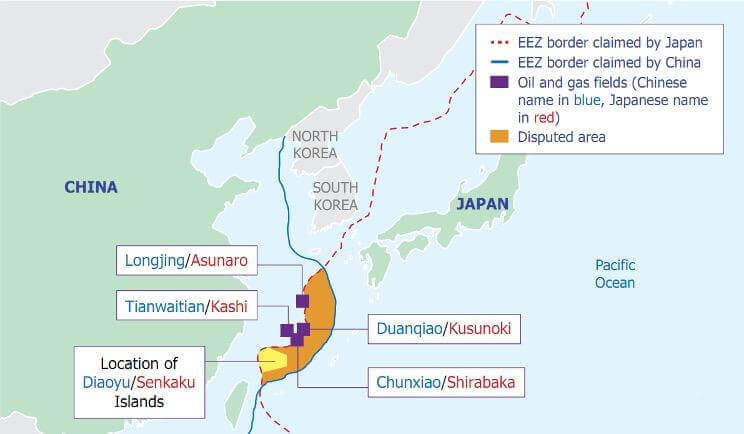

To understand that Taiwan is the keystone to Beijing’s full naval projection, we must look to our third teacup, this time east of Taiwan. The situation is arguably identical to that of the Philippines: A coastal nation’s claims abut against those of an archipelagic state. In this case, the oil and gas fields have already been developed by China.

We are compelled to consider how these circumstances might change were Taiwan an independent country. As an island, its claims as an archipelagic state would gain in legal force what Beijing’s pushy insistence could never provide: international legitimacy. We note in passing the irony of the One China policy’s contradiction with the objectives of the Nine Dash line, only to point out how much there is to gain from a peaceful resolution to these matters.

To be clear, the only way for Japan to lose their Senkaku Islands is for Taiwan to declare independence. The same goes for the concatenation of claims that stretches down to the Spratlys: Taiwan’s chances of winning that case are much better than China’s, especially considering that Beijing already lost the case.

Keep this in mind as we go down the AUKUS rabbit hole. The possibility that one or more of Australia’s new wolfpack of nuclear-powered submarines just might also be carrying a nuclear bomb is enough to modify the strategic calculus of nuclear balance in the region. Nowhere outside Europe are there so many nuclear-armed nations in such close proximity.

The details are fascinating: Where India’s ICBM doctrine swears off battlefield nukes—restricting its nukes to world-ending scenarios—Pakistan’s force of mid-range delivery systems make it clear that their deterrent is targeted at someone specific (India, but most of China is also in range). North Korea, whose nuclear weapons program is a proliferated child of Pakistan’s (itself a bastard of British origin by way of the recently departed A.Q. Khan) has developed delivery systems to threaten other continents (including Oceania, in case anyone is keeping track). At this point, ideas that seemed radical a decade ago—like unifying a Nuclear Korea—are getting a hearing in establishment venues.

China itself has long been a nuclear weapons state. Recently caught digging holes for ICBM silos, it is safe to assume the rest of their nuclear triad will also be receiving attention, love, and a bigger budget. And now (surprise) they have a supersonic delivery missile system. And then there’s Russia, on the northern side of the Chinese border, with the largest nuclear weapons stockpile of any country in the world, having pulled out of the INF treaty which dealt specifically with mid-range nuclear-tipped cruise missiles (as opposed to the kind you need a spaceship to launch into orbit).

Asia is a tinderbox of nuclear weaponry waiting for a match.

Beijing considers this status quo to be unbearable. The only exception to its nuclear encirclement is in Central Asia (and even then, only because Kazakhstan handed its nukes back to Russia). The sea to China’s east is contained by the first and second “string of pearls”—islands which bear allegiance, variously, to France, the United States, Australia, the UK, or New Zealand. The seas to China’s south depend on the choke point at Malacca—Singapore’s great fortune. Hydrocarbon stockpiles in Beijing can be decided from Malacca, by force of arms if need be.

So how can the Chinese Communist Party climb down from their current predicament? Knifing Xi Jinping would buy a lot of time, but the so-called, “Paramount Leader” has successfully nestled himself into a position of absolute power, or so the best “kremlinological” efforts report.

The real and best solution, however, is for Taiwan to declare full sovereignty and independence. Beijing’s face may need saving by, for example, casting Taipei out á la Singapore and Malaysia. But make no mistake—Central Asia’s Stanistan will not sate Beijing’s appetite for long, nor will she allow herself to be bound, lashed and channeled in that (undoubtedly productive) direction.

Pride is the father of all sins, and the Chinese communists seem unable to receive a humbling without tearing it all down. That time, alas, has come.

Pity the poor Chinese peasant—they haven’t asked for the tempest that is about to come. The preferred plot: Taiwan needs to declare its freedom formally, and now.