“[The attacks] . . . were the greatest work of art imaginable for the whole cosmos. . . . Minds achieving something in an act that we couldn’t even dream of in music, people rehearsing like mad for 10 years, preparing fanatically for a concert, and then dying, just imagine what happened there. You have people who are that focused on a performance and then 5,000 people are dispatched to the afterlife, in a single moment. I couldn’t do that. By comparison, we composers are nothing. Artists, too, sometimes try to go beyond the limits of what is feasible and conceivable, so that we wake up, so that we open ourselves to another world.”

“One good thing could come from this horror: it could spell the end of the age of irony. For some 30 years—roughly as long as the Twin Towers were upright—the good folks in charge of America’s intellectual life have insisted that nothing was to be believed in or taken seriously. Nothing was real. With a giggle and a smirk, our chattering classes—our columnists and pop culture makers—declared that detachment and personal whimsy were the necessary tools for an oh-so-cool life. Who but a slobbering bumpkin would think, ‘I feel your pain?’ The ironists, seeing through everything, made it difficult for anyone to see anything. The consequence of thinking that nothing is real—apart from prancing around in an air of vain stupidity—is that one will not know the difference between a joke and a menace.”

In 1998, when Bill Clinton lobbed missiles at Sudan and Afghanistan, it was widely derided as a “wag the dog” phenomenon, war as a diversion from the real. Earlier wars had suffered from the same criticism, most notably Jean Baudrillard’s assertion that the first Persian Gulf War “did not take place.” The 1990s were the peak of the application of the postmodern prism to political and social reality. It was the heyday of movies like “The Matrix” (1999), “The Truman Show” (1998), and “Pleasantville” (1998), among numerous other Hollywood productions that questioned the nature of identity and reality. The Coen brothers’ “The Big Lebowski” (1998) is an exemplary movie of the era whose plot can be said to be about “nothing,” in the sense that no resolution in the conventional sense is sought; it reminds one of the stop-and-go plot movement of anime movies such as “Spirited Away” (2001) or “Your Name” (2016), which seem to start over and over again, a Japanese aesthetic disconcerting to Western audiences used to Aristotelian plot development. The “nothing” is important, as it was often evoked with reference to “Seinfeld” as well, and much of the irreverent comedy of that era, before the return of politics to comedy in such acts as Chris Rock and Lewis Black, not to mention the politicization of satire on Comedy Central. Art, in general, was emptied of grand narratives, as even faint attempts at meaning came with such an overload of irony that the attempt to “make sense” was futile.

9/11 was the crucial before-and-after event, following which the irony that had been escalating since the formation of the modern American empire in the wake of World War II and had reached a crescendo in the 1990s was relegated to oblivion. At the time it wasn’t clear whether this could actually be accomplished, whether irony was too strongly rooted in the culture to actually be foreshortened, but what stands out at a distance of 20 years is that not only was it possible but in both elite and popular culture it has been fully realized to an extent that would have been inconceivable two decades ago. This is the single most important change that has occurred in the American polity in these years, and it defines every event of consequence in every area of existence—even personal life, to the extent that it is publicly transcribed and made visible.

The move from postmodern irony, with its skepticism toward grand narratives and political teleology (not to mention facile ideology), to a post-postmodern realism, which frees politics from unstable interpretation, has recharged capitalism in a way that would have been unimaginable before it happened.

This is true despite the onslaught of new technologies which earlier would have been theorized as working against realism but which have in fact supported the establishment of precisely the kind of realism that would suggest the impossibility of these devices of communication. In other words, Facebook, under postmodern theory, should be completely the opposite of the actual entity it has become, namely a force for increased gravitation and solidity, rather than liberation from the technology’s tentacles of self-surveillance and impersonal categorization.

So what exactly have we lost?

Postmodern Absurdity

Postmodernism posits the assertion of globality or interconnectedness between nations and entities, glancing beyond the “end of history” thesis to provoke further convolutions in capitalism’s international trajectory. It contests the stable bourgeois subject to a far greater extent than modernism attempted, prioritizing modes of information over the Marxist modes of production as the next great site of resistance. It establishes simulacra as per Baudrillard to see through events that do not even make an attempt at opacity, empowering deconstructive readings of texts to separate language from reality. It prefers polyvocality in the Bakhtinian sense over univocality (so that even science is not privileged as under modernity), incorporating the polarities of subject positions in a continuously fluid explanation of change. It distinguishes new grassroots movements from the old Marxist class conflict heuristic, positioning the other at the center of analysis rather than accepting otherness as a sideshow. Above all, it refutes, as per Lyotard, the grand narratives of capitalism in favor of more local, individual, intimate, and multiple narratives, which might well lead to divergent conclusions.

To a large extent, this state of affairs prevailed not only in the academic world prior to 9/11 but also at the popular level, even if ordinary people did not use postmodernism’s often pretentious language. They had the sense, however, to laugh at patent absurdities, and more often than not they came up with ways to identify absurdities to celebrate, in a way that the old Situationists would very much have appreciated. The Republicans tried to paint a demonic picture of Bill Clinton by way of the Monica Lewinsky scandal, but for the general population a blowjob was just a blowjob, and the president’s shape-shifting identity remained more hypnotic. Clinton remained hugely popular until the end, while the puritan hustling of Newt Gingrich and company came in for sustained derision.

In every respect, the ideals of postmodernism, as outlined above, manifested at a deep level, to the extent that vital centrists in the Arthur Schlesinger mode futilely evoked the unity and faith of the 1950s as ideals worth reviving to counter what they decried as the “Balkanization” of America under the onslaught of identity politics, textual deconstruction, respect for the outré (and unAmerican) other, and general uninterest in establishing a form of global hegemony that made sense at the gut level. Though Clinton tried to reach for just such an overarching theme, he is generally perceived to have failed, despite it being the era when neoliberal globalization came into its own, from the creation of NAFTA to an infinitely malleable mission for NATO, from the glorification of personal responsibility to the increased punitiveness of the carceral state. Those who rose to power in the wars that followed 9/11 used to lament that a grand narrative was not available to Americans after the demise of the Soviet Union and that this could well portend the end of the American empire before it had reached its climax.

In many ways, this state of affairs was more desirable than the return to “reality” we have lately witnessed. In the absence of ideological coherence, there was widespread skepticism of official narratives, which generally precludes war or other misguided bureaucratic adventures. One of the realms most affected by postmodern skepticism was science, whose advances were taken in stride rather than accepted unquestioningly, such as when Dolly the sheep was cloned or the human genome was decoded.

An important aspect of this was the personalization of science, especially with respect to individuals taking charge of their bodies to an extent that had not been seen in America since the advent of modern medicine. If there was a positive side to personal responsibility, which often devolved into neoliberal punitiveness under the regime established by Clinton and his successors, then assimilating the body and its processes under a subjective and highly individualized lens was it. None of this is to say that the wars of empire (presented in the guise of “humanitarian” intervention, such as in Bosnia or Kosovo, or lamented for their absence for precisely the same reason as in Rwanda) did not continue unabated, or that the personal responsibility narrative capitalism latched onto did not create forms of misery that can only be explained as a new serfdom, but there was a sense throughout the 1990s that the ground beneath these formulations was shaky indeed and could not last in perpetuity.

Thus the tremendous hope, felt around the globe at the turn of the millennium, in the shape of promises to redo the entire international order, not to create a new grand narrative but to revel in the pervasiveness of postmodern subjectivity. The local would remain independent, in this idealistic interpretation, free from totalizing myths, which only lead to ruin. So there would be an empowered international criminal court and concerted efforts on debt forgiveness, but local cultures would be appreciated and preserved, despite the rumblings of a conservative minority resisting what they called “cultural relativism.”

The transformation from postmodern irony to a stable subjectivity often mired in grief and physical limitations happened almost overnight. To go from Quentin Tarantino’s “Pulp Fiction,” which embodied non-chronological discontinuity in the postmodern vein, to his more recent movies such as “Inglorious Basterds” (2009) and “Django Unchained” (2012), is to establish a myth of revenge, retribution and just recompense in a universe that actively collaborates with the aggrieved subject. The Coen brothers went from The Dude’s do-nothing ethics in “The Big Lebowski” to “The Serious Man”’s (2009) relentless search for meaning even in the shallows of antiquated mythology. “The Lovely Bones” (2002), Alice Sebold’s hagiography of a dead teenage girl who finds peace and salvation after being brutally murdered, established a trend in fiction, and after that in memoir, that shows no signs of abating 20 years later.

It doesn’t seem to be a coincidence that Kenneth Lonergan’s “Margaret” (released 2011), which encapsulates the transformation of the free-flowing subject into one that self-limits and revels in grief and blame, had such a difficult time getting distributed. It was conceived not long after 9/11 but did not see the light of day, and even then only in truncated form, until the 10th anniversary of the fateful event. It was too truthful, and even today it penetrates the new grand narrative with painful jabs.

The Return of the Narrative

The grand narrative that has been resurrected, after the dire lack in the 1990s, is that of the desperate need to return to “normality”—this ideal referent holds true whether it is after 9/11, or the financial crisis, or most recently COVID-19—which is constantly strengthened by way of different forms of fear that threaten to undermine said normality. Of course, this is a normality that was under severe assault during the postmodern peak from the 1970s to the 1990s (the Reagan years included), taken apart and deconstructed from an anti-patriarchal, anti-nationalist, anti-racist, and often even anti-religious perspective. Normality is everything that postmodernism undermined, as the recharged stable subject is energized by the need for security. Everyday life, in other words, is reillumined by the transcendent capitalist myth, even as the grand narrative takes care not to indulge in bouts of communitarianism but remains limited to individual responsibility.

What about the rise of new oppositional grassroots movements in the “after” period? It is interesting that Occupy Wall Street was in part prompted by the culture jamming disseminated by the Canadian Adbusters magazine, which was a Situationist spectacle updated for an era of consumerism devastated by heavy student debt and permanent job insecurity. From these small beginnings, it burgeoned into a nationwide movement, but at the same time, it gradually became transformed by the same grand narrative that capitalism now prefers, namely that scarcity (which is reflected in insecurity) is the order of the day and that nearly all the battles that had been fought and often won by the labor movement need to be fought all over again.

Thus it is interesting to see millennials and post-millennials pursue the fight for a $15 minimum wage, student debt forgiveness, and Medicare for All as though the Golden Age of American capitalism (roughly from 1945 to 1973, and lasting even later, almost until the end of the Cold War) had not made those realities—a living wage, more or less free college, and affordable health care—already possible. The same applies to abortion rights, or voting rights, or the fight against police brutality, which the country had moved beyond in many respects. I remember well the relatively enlightened attitude of the police in Los Angeles and San Diego in my earlier years, when the departments were interested in notions of racial equity that seem to have been pushed far into the background now, receding as impossible ideals.

The post-scarcity society, a staple of postmodern theory, has been long forgotten, and it is a tragedy. Young people fall into the trap of taking things as real that have no business being treated as such and vice versa. The idea that a decades-long struggle must be mounted to regain some basic elements of economic equity only lately discarded is a hopeless whim. Oppositional movements were much better off when they presumed the unreality of the political setup and acted accordingly. “Dr. Strangelove” (1964), “Apocalypse Now” (1979), and “Brazil” (1985) represented the absurdist aesthetic that saturated America in earlier decades, ironically providing the only firm basis upon which to mount opposition, namely from a stance of dismissing the economic base as necessary or relevant. Contrast this to the overwrought seriousness of a deeply flawed movie like Paul Thomas Anderson’s “There Will Be Blood” (2007), which accepts the reality of the physical order of capitalist extraction, and the way human beings bend under its will, allowing no room for escape or enlightenment.

Daniel Boorstin’s The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America (1962) actually held sway throughout the counterculture era and for a couple of decades after its peak. It understands that Baudrillardian simulacra, or the pseudo-event in Boorstin’s terms, drives manufactured democracy or the appearance of vigorous contest in the public sphere (I am intentionally teasing Chomsky’s idea of manufactured consent), while actually hiding the end of ideology—and without explicit ideology, there can be no progress, no humanity, no enlightenment.

Postmodernism was more suited to the American political and cultural structure in offering avenues of true contestation because one should not treat the unreal as real, but it also allowed openings to ideology, which is ironic, given that postmodernism is driven by opposition to grand narratives. What we have now, in the return to reality, is a cover for ideology, except that the ideology has been seized by an oligarchy of media barons, Silicon Valley entrepreneurs, and overvalued celebrities who freely distribute it while denying that they are ideological.

The reconstruction of “scarcity”—in the form of rationing higher education by way of steep tuition costs, or the segregation and displacement of working-class people in all the important cities through what is euphemistically called “gentrification”—is a big part of this posture, which is presented to the struggling subject as a real and ever-present threat, rather than an impossible occurrence based on society’s actual resources and possibilities.

In a mode of perpetual crisis, emotionally overwrought people delegate rationality to experts, which has been manifest in the resistance to treating the Trump phenomenon as a matter of political give-and-take and instead treating it as a law-and-order crisis best dealt with by experts in the security industry, manifesting in Russiagate and repeated efforts at impeachment. A postmodern anomaly political scientists struggled with throughout the 1990s was Clinton’s low personal rating combined with high policy approval, a paradox Trump manifested too, except that liberal defenders of authority chose not to make peace with the contradiction this time. Also, Clinton was the last president whose policies were driven by polls, while every president since then has ignored polls in making key policy decisions.

Note too that by the time of the mid-1970s Church Committee investigations into the CIA’s historical misdoings, and the revelations of the FBI’s COINTELPRO and other anti-grassroots programs in the same time period, the national intelligence agencies stood fully discredited; the same was true of the ravenously snooping National Security Agency (NSA) in the 1990s, which was treated with disdain after the end of the Soviet Union amid relentless questioning of its aims and orientation. Privacy became one of the most important public policy arenas in the 1990s, enhancing postmodernism’s interest in the individual subject’s sphere of authenticity, and it is this value that has been most demolished in the ensuing era.

Weaponizing Capitalists

What are some examples of recruiting willing capitalist subjects to fight fights that are not worth fighting because they are not even real?

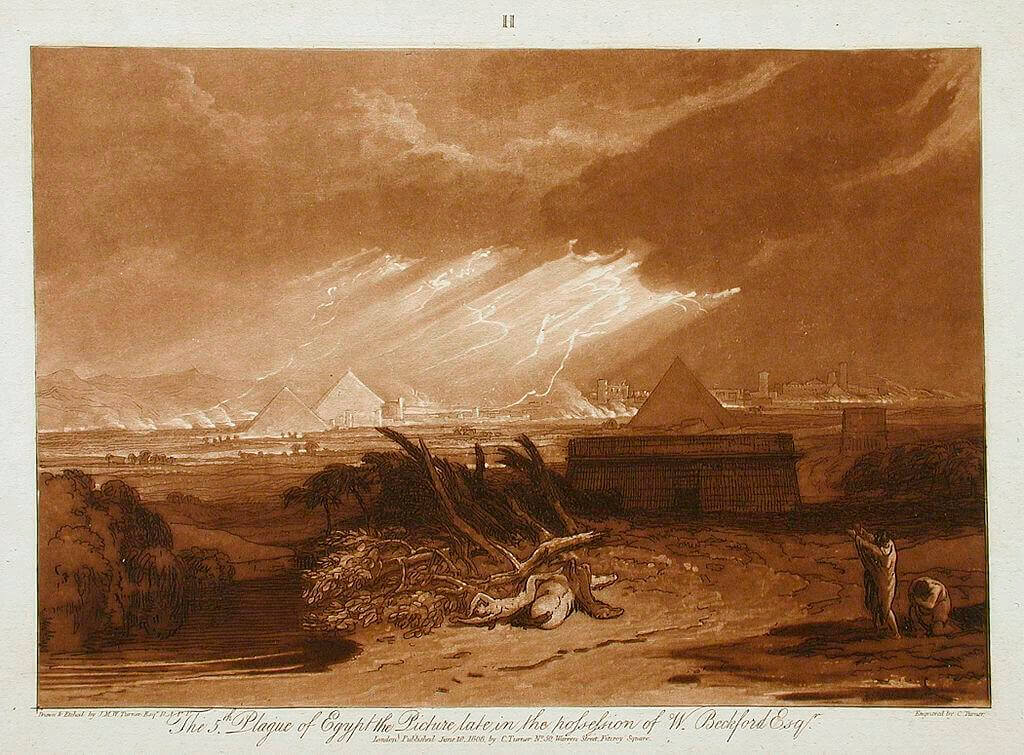

The war on terror—in response to the most terrifying and therefore most “real” image capitalism could muster to embody insecurity, namely the collapse of the towers in the mushroom rubble—was the most fantastical idea of all, an illusion so radical as to defy belief other than by the most credulous, except that the entire country bought into this credulity. While Afghanistan offered to extradite Osama bin Laden even before the start of the war, the United States chose to invest 20 years and trillions of dollars of resources into a war with ever-shifting goals and parameters, neatly simulating the pacification strategies of the already discredited Vietnam War.

When Katrina drowned New Orleans, our sense of “reality,” brought home by televised images of devastation, focused our minds on relieving the suffering of the residents of the Ninth Ward and other affected areas of the city, while leaving alone the consumption of fossil fuels and the obvious destruction of ecological spheres everywhere due to this reckless consumption, of which Katrina was a surface manifestation.

When the financial crisis hit, we again believed the experts who told us that irresponsible lending and borrowing under the rubric of subprime mortgages was the culprit, while leaving the guilty financial system, overloaded and impossibly top-heavy, not only alone, but even more empowered than before the crisis.

And finally, in the wake of the COVID pandemic, we have a division in the country between those who give absolute credence to scientists in order to oppose the “vaccine skeptics,” forgetting the modern history of medicine in particular and science in general, which as often as not have been allies of capitalist reductionism, bringing about suffering and misery on a transcendental scale, and also staying focused on immediate and apparently the only “real” tools of alleviation, such as vaccines created in short order, rather than addressing the health crisis that makes populations vulnerable to such pandemics. Imagine the trillions of dollars (again, rebelling against the false notion of scarcity, which postmodernism had once penetrated) aimed at various forms of stimulus, often benefiting the elite medical establishment, redirected to free and healthy food for the entire country, in addition to rent and debt forgiveness, not to mention universal health care at last.

The form of reality, driven by constant challenges of insecurity and terror, that is the basis of the new grand narrative for capitalism in America, militates against thoughtful action, even deliberation about one’s own interests, which is another way of describing the exploration of common interests. The subject is solidified into a new singular body with limited goals and needs, never able to escape omnipresent threats which take it farther and farther away from the very normality that is sought. Tactics of opposition and refuge that were successful in the past, which need to be based on unstinting support for freedom of expression and movement, are reconceptualized as potentially terrorist activities, because they break with the ever-uncertain normality.

The current jargon of authenticity, to borrow Theodor Adorno’s terminology, leads to an imprisoned subjectivity, propelled by despair as the only real value. Every time there is a “new normal,” and there always is, we recede farther into unreality, and the ideology of capitalism becomes all the more shrouded. The prison is unreal, and the spectacle of misery self-renewing; but how can we who remain inside the cage and accept our punishment know it?