Demagogues appeal to envy because they believe that promising to destroy the advantages enjoyed by others will win votes and inspire loyalty. Sometimes it does. As the envy-driven horrors of Rwanda and Nazi Germany demonstrate, pledging to disrupt the envied lives of a despised “other” can be a ticket to victory for a political candidate savvy enough to convince voters that he has their best interests at heart.

More than 25 years ago, Doug Bandow, a senior fellow at the Cato Institute, pronounced in his book The Politics of Envy: Statism as Theology that we “live in an age of envy.” Pointing out that “people don’t so much want more money for themselves as they want to take it away from those with more,” Bandow suggested that although “greed is bad enough, eating away at a person’s soul, envy is far worse because it destroys not only individuals, but also communities, poisoning relations.” A Christian libertarian, Bandow wrote that

those who are greedy may ruin their own lives, but those who are envious contaminate the larger community by letting their covetousness interfere with their relations with others.

One can satisfy greed in innocuous, even positive ways—by being brighter, working harder, seeing new opportunities, or meeting the demands of others, for instance.

In contrast, envy today is rarely satisfied without the use of the coercive power of the state: “The only way to take what is someone else’s is to enlist one or more public officials to seize land, impose taxes, regulate activities, conscript labor, and so on. Statism has become the basic theology for those committed to using government to coercively create their preferred version of the virtuous society.”

Bandow views statism—the out-of-control growth of government power to confiscate the property, wealth, and labor of others—as a grave threat to both traditional religion and human liberty. He worries greatly about the growth of government because he believes that much of that growth was built on envy; and he encourages Christians and libertarians to find common cause in the goals of preventing the growth of what he called the “false god” of stat- ism and of returning our society to one in which both virtue and freedom flourish. Politics in Bandow’s “age of envy” has resulted in a desire not to produce more for oneself, but to take as much as possible from others.

Bandow was prescient about the growth of government and the envy that has driven it. He would not be surprised that the secular atheist ideology that has grown over the past two decades distorts our understanding of reality. Those distortions work to hide the true goal of politics under atheism, which is, of course, power. Once God is banished, we become creatures not of God but of society politics, and we then have the choice either to rule or to be ruled. The stakes can be no higher because, for the secular atheist, man is the highest thing, and so power among men is the highest good. That is why everything is now political and why people lose their minds over elections.

Bandow understands that there will always be a significant portion of the population who will vote for the candidate who promises to take away the most wealth—and sometimes the very freedom—from the greatest number of “undeserving” people. But the 2016 election of President Donald Trump disproved the theory that promoting the envy of the rich helps to win elections. Rejecting progressive promises to destroy the rich and the powerful, voters awarded Trump with the presidency because he reassured them that America can again be the “envy” of others if we are willing to change course. Trump knew that most of us do not envy the rich—we admire them. We may even want to emulate them. He understood that for most of us, our dreams are not to hurt those who have more than we do. We just want to have good jobs that pay us enough to support our families and make us feel secure.

This is not to say that President Trump did not acknowledge that we often want to blame others when we experience hardship. And, although his message in the 2016 election was subtle, there were undercurrents of an appeal to envy in Trump’s promises of “greatness” for Americans. Conservatives can, of course, be envious.

As Helmut Schoeck writes, “Envy is politically neutral. It can be equally mobilized against a socialist government that has been in power since living memory, as against a conservative or liberal one.” The decisive difference is that the nonsocialist politician will always direct the voter’s envy or indignation and resentment against certain excesses, the extravagant spending, the way of life, the nepotism of individual politicians. The conservative candidate will not pretend—as the socialist-leaning candidates do—that once he is in power, his aim will be a society in which everyone is equal and that there will be nothing to envy. Trump never promised an egalitarian society. Rather, he promised greatness—a society that others would envy—and this is what helped him win the presidency.

Political Theory and Envy

The earliest philosophers warned of the evil of envy and resentment. In On Rhetoric, Aristotle described envy as “the pain caused by the good fortune of others.” Stressing the importance of propinquity and the threat of competition, Aristotle adds that “we envy those who are near us in time, place, age or reputation,” and he adds that those who envy do not necessarily want to emulate the object of the envy. In fact, in the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle suggests that emulation is felt most of all by those who believe themselves to deserve certain good things that they do not yet have. It is felt most keenly by those with an honorable or aristocratic disposition. In other words, while envy is the reaction of those with low self-esteem and a resentful outlook, emulation is the reaction of those with high self-esteem and an optimistic outlook on the future.

Philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) observed that rather than seeking their own happiness, the envious devote their energy to “destroying the happiness” of others. In The Metaphysics of Morals, Kant described envy as “the vice of human hate,” a moral incongruity that delights in misfortune. In describing Kant’s views on envy, psychotherapist Joseph H. Berke writes in Why I Hate You and You Hate Me: The Interplay of Envy, Greed, Jealousy and Narcissism in Everyday Life that envy is a “hate that is the complete opposite of human love. The impulse for envy is thus inherent in the nature of man, and only its manifestation makes of it an abominable vice, a passion not only distressing and tormenting the subject but intent on the destruction of the happiness of others, and one that is opposed to man’s duty towards himself as toward other people.”

In her book Envy In Politics, New York University professor Gwyneth McClendon points out that in Leviathan, Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) suggests that it is envy itself that differentiates humans and animals because “animals have no other direction than their particular judgments and appetites.” While animals are driven by the need for survival, human politics emerge from a desire to be distinguished, even if that means conflict and hostility. For Hobbes, envy is grief at the prosperity of another—especially one who is close in status to the one who is envied—and is related to the drive for power. Because of this, a successful political order needs to take into account man’s selfish and envious nature. John Rawls uses the term “envy” to help explain the propensity to view with hostility the greater good of others—and a willingness to deprive them of their greater benefits even if it is necessary to give up something ourselves. Likewise, Alexis de Tocqueville (1805–1859) pointed out that sometimes people can be so concerned about status that they will pursue status at the expense of their own interests.

Both John Stuart Mill (1806–1873) and Adam Smith (1723–1790) viewed envy as a powerful motivating force. Mill placed envy as an antisocial vice that needed to be regulated because it involved a “breach of duty to others.” While Mill calls envy “that most anti-social and odious of all passions”—placing it among the moral vices that must be regulated because the sin “involves a breach of duty to others,” Adam Smith acknowledged the danger of envy in Wealth of Nations but believed that the emotion is overridden in most people by more “prudential considerations.” Smith minimized the danger posed by envy, preferring to highlight human beings’ desire for admiration and distinction in the eyes of others. Claiming that such a desire for status can help one to live up to that distinction, Smith sees some value in status striving—even when driven by envy.

Envy Drove the Creation of the Progressive Income Tax

Even though Adam Smith did not see envy as an evil in the way Mill and Hobbes did, Smith acknowledged the irrationality of status motivations when he suggested that we all have a basic desire to achieve distinction in the eyes of others—even when it does not bring other benefits. In this, Smith reflected the spirit of America’s founders, who rejected the envious motivation behind the current progressive income tax—that the more you earn, the larger the percentage of tax you must pay.

In Federalist 10, James Madison dismissed the idea of taxing what he called the “various descriptions of property” because he knew it would begin to destroy the rules of justice. The 14th Amendment promised equal protection of the law to all citizens, and early attempts to “tax the rich” met with legislative failure. In 1894, when Congress passed an income tax that was levied on only the top two percent of wealth holders, the Supreme Court ruled it unconstitutional because it targeted only one group. Writing for the majority, Justice Stephen Field repudiated the congressional action and predicted that if such a tax were allowed, it would be the “stepping stone to others, larger and more sweeping, until our political contests become a war of the poor against the rich.”

Justice Field was prescient. Less than two decades later, campaigning on a platform of “soaking the rich,” legislators promoted a constitutional amendment in 1913 permitting a progressive income tax. In these early days, the top rate was kept at a low seven percent. But, just as Justice Field feared, only a generation later, in the midst of the Depression, Herbert Hoover and Franklin D. Roosevelt claimed that the economy demanded extreme measures. Under Hoover, the top rate was hiked to 64 percent, and once the Democrats took control of the White House, Roosevelt raised the rate to 90 percent. By 1941, Roosevelt proposed a 99.5 percent marginal rate on all incomes over $100,000. Although his proposal was not successful, Roosevelt issued an executive order to tax all income over $25,000 at the rate of 100 percent. Congress repealed the presidential order but retained the marginal tax rate of 90 percent on top incomes. Today, the progressive income tax is so taken for granted that few even recall that there was ever a debate over the constitutionality of such a tax.

Psychologists have long known that achieving status within our own reference group brings pleasure and a sense of personal power and is more closely linked to self-reports of well-being than many measures of absolute welfare. When we think we are falling behind those in our reference group, we begin to feel a sense of status anxiety. And from the earliest days of the fledgling discipline of sociology in the 19th century, sociologists have been concerned with status issues—including status envy. Emerging in the midst of the chaos that had accompanied urbanization and the industrialization of the economy, sociology was created to try to understand what holds social groups together during times of rapid social change and to explore possible solutions to the breakdown of social solidarity.

While early sociologists such as Émile Durkheim stressed the “ties that bind us together,” Karl Marx teamed with wealthy industrialist Friedrich Engels to address the growing inequality that they believed was tearing society apart. Writing at the height of the Industrial Revolution, when factory owners were accumulating wealth and factory workers remained mired in poverty, Marx and Engels attacked the growing income gap, claiming that it was capitalism that perpetuated these inequalities. Marx believed that the accumulation of capital or property was an obstacle to progress because any inequality in wealth meant that someone was exploited.

For Marx, capitalism required the exploitation of the workers in order to provide profits to the owners. And although Marx viewed capitalism as an inevitable stage in the history of the world leading to “the millennium of socialism,” he drew upon themes of envy toward the rich to gain support from the masses in order to destroy the capitalist system. This is still true today as the Marxist promise of “fairness” to the proletariat was a promise of a utopian world in which all conditions that produce envy will disappear.

The Myth of Social Justice

Today’s Marxists argue that the egalitarian world that socialism can create removes all targets of envy so that the envious have nothing to envy. Yet envy creates its own targets, regardless of how equal people may appear to be. The fact that there has never been a socialist society that brought about such utopian classless conditions is dismissed by the Marxists, who believe that such examples of socialism have not gone far enough in redistributing the wealth equally. A recurring theme throughout much political thought has been that envy supplies the psychological and sociological foundations of the concern for egalitarian conceptions of justice. True egalitarians want to do away with the advantages of the better off. They wish to do this because they are unhappy that some have “more” than they do.

According to economist Friedrich Hayek (1899–1992), “social justice rests on the hate towards those that enjoy a comfortable position, namely, upon envy.” In The Mirage of Social Justice, Hayek suggests that social justice is a notion that lacks a rigorous meaning since no one has been able to determine, except in the marketplace, what would be the absolutely just distribution of the patrimony and income in a mass society. Suggesting that the phrase social justice had become a source of “sloppy thinking and intellectual dishonesty,” Hayek believed that using the phrase was “the mark of demagogy and cheap journalism which responsible thinkers ought to be ashamed to use because, once its vacuity is recognized, its use is dishonest.”

Describing social justice as “that incubus which today makes fine sentiments the instruments for the destruction of all values of a free civilization,” Hayek warned that the continued unexamined pursuit of “social justice” will contribute to the erosion of personal liberties and encourage the advent of totalitarianism.

Drawing from Hayek, Gonzalo Fernández de la Mora (1924–2002) suggests in Egalitarian Envy, his own treatise on the danger of envy, that “egalitarianism is the opiate of the envious and demagogues are the self-interested distributors of its massive consumption.” Echoing Hayek, de la Mora writes, “the realization of what is called social justice requires economic planning and delegation to the public powers of the authority to assign work, rewards, and salaries to every citizen. Within a totalitarian system, this monopoly is equivalent to the tyranny of only one party; and within a democracy, it implies the tyranny of the majority, for in order to please its electoral clientele, it must expropriate the minorities. This is how theoretical social justice may turn out as effective inequity.”

For de la Mora,

what the Marxists usually call social justice is the policy of inspiring the less productive to demand that the state carry out transfers of goods by expropriating those who produce more, humbling the superior to satisfy the inferior. This maneuver is no doubt a political use of envy. The generalization of such a practice very often makes it possible for the topic of social justice to become the pharisaic institutionalization of collective envy or a tacit concession to placate it. Interventionism leads to increasing controls and therefore to the progressive elimination of private initiative, and actual liberties end up being destroyed by totalitarian models. Egalitarian distribution without regard for individual merits and demerits is inequality rather than justice.

In an attempt to “rescue it from its ideological captors,” Michael Novak and Paul Adams provided an alternative Catholic definition of social justice in their 2015 book, Social Justice Isn’t What You Think It Is. Challenging both progressive and conservative approaches to social justice, Novak and Adams suggest that defined properly, social justice represents an “immensely powerful virtue for nurturing personal responsibility and building the human communities that can counter the widespread surrender to an ever-growing state.” In the introduction, Adams dismisses the ideological version of social justice that “provides a justification for any progressive-sounding government program or newly discovered or invented right.” He also criticizes the ways in which some have branded opponents as “supporters of social injustice, and so as enemies of humankind, without the trouble of making an argument or considering their views.”

Novak and Adams emphasize social justice as a virtue and aim to recover it as a useful and necessary concept in understanding how people ought to live and order their lives together. They attempt to clarify the term’s definition and proper use in the context of Catholic social teaching—applying it in the context of democratic capitalism, in which, they argue, “social justice takes on a new importance as a distinctively modern virtue required for and developed by participation with others in civil society.”

The Catholic definition of “social justice” has the potential to counter the threat of secular, atheistic, and collectivist social movements—like the current movement toward “democratic socialism”—because it involves a readiness to “make some sacrifices” to maintain the health and strength of society. Recall that the basic idea behind true social justice has its roots in Aristotle and in medieval thought—then called “general justice.” It pointed to a form of justice whose object was not just other individuals, but the community.

Unfortunately, as Hayek pointed out, most of those who use the term today do not talk about what individuals can do. They talk about what government can do. They talk about social justice as “a characteristic of political states . . . remedied by state-enforced redistribution.” Once social justice is redefined as a state intervention involving confiscation, it loses its status as an individual virtue, and as Hayek claims, “if social justice is not a virtue, its claim to moral standing falls flat.”

Contemporary political theory helps to explain the status motivations that shape voting behaviors and other political decisions. In the 1950s, research by Richard Hofstadter found that shifts in prestige across entire communities prompted individuals who had lost relative status to become progressives, so that they could push for reforms to gain higher incomes and levels of education.

Status inconsistencies—when individuals have high status in one dimension, such as education, and low status in another dimension, such as income—will be more likely to support progressive political parties that favor social change. This helps to explain why the majority of Ph.D.-level professors on college campuses throughout the country describe themselves as progressives and are the strongest supporters of social justice and coercive egalitarianism.

In an attempt to understand how envy operates in political behavior, Gwyneth McClendon analyzed what she sees as “puzzling” political behavior or voting behavior that is chosen even though it is contrary to one’s own interests. In Envy in Politics, McClendon suggests that when looking at the policies we support and the politicians we vote for, we should pay attention to envy, spite, and the pursuit of admiration—all manifestations of our desire to maintain or enhance our status within groups. Drawing from Hobbes, McClendon points out that we often pursue a higher relative position for its own sake, even when doing so incurs no material benefits, except a possible improvement in one’s social status. Analyzing empirical political behavior data, McClendon began her study with these questions: “Why do citizens sometimes support redistribution and taxation policies that go against their material self-interests? Why do politicians sometimes fail to implement funded policies? Why do citizens sometimes participate in political events even though it is personally costly to do so?” Her answers often focus on status motivations.

To understand status motivations, McClendon conducted an experiment in which members of an organization’s LISTSERV received one of three emails encouraging them to attend a protest. Some were simply asked to attend; others were told that their participation was “admirable” and because of that their names would be listed in a public newsletter; and the third group was told that participation in the protest was admirable and invited the participants to post on Facebook photos of their participation. The results revealed that those offered the chance to have their names posted in the newsletter showed up at levels 76 percent higher than those who were simply invited. The desire to be admired was the major motivation for those who attended the protest.

McClendon found that “within-group status” helps us understand why people vote the way they do. She points out that people may be “willing to support costly policies and undertake costly actions when doing so wins them this other valued good. Status motivations help explain political behavior that is materially costly to the individual but that has within-group distributive implications of income or esteem.”

Although she expected that the widespread beliefs in social mobility, individualism, and the American Dream in the United States might have muted desires to punish others for their success, she found that status concerns—including envy and spite—continue to motivate political voting behavior that hurts others’ upward mobility while doing nothing to improve one’s own position. The central insight from McClendon’s study is that to understand more fully the political implications of inequality in any era, we need to focus on patterns of local, within-group inequality; we need to consider not only that people are self-interested, within-group biased, and concerned about fairness but also that under some conditions, they are willing to pay costs (and even see others harmed) for the sake of achieving higher status within their own groups.

The “NeverTrump” movement that emerged within the Republican Party during the 2016 presidential primaries and continued through the early years of the Trump presidency relied on these concerns about within-group status among those who oppose Trump. Even though Trump may have significantly improved the economic position of most Americans, some within the NeverTrump crowd have continued to deny that he deserved any respect and certainly not their vote in 2020. To support the president openly would bring an unwelcome decline in within-group status for high-profile NeverTrumpers such as Bill Kristol, the founder and editor of the now-defunct Weekly Standard, who has enjoyed high status because of his frequent media appearances on progressive cable television news sites where he continues his attacks on Trump.

Still, there are many more former Trump foes who came to realize how much their opposition was mistaken. Such a course correction would effectively preserve their within-group status. The New York Times chronicled the journey from “NeverTrumpism” to Trump support by media stars such as Glenn Beck, the radio host who once called Trump “an immoral man who is absent decency or dignity” but who later said that Trump’s defeat in 2020 “would mark the end of the country as we know it.”

Similarly, Erick Erickson, a conservative radio personality and prominent NeverTrumper who said in 2016 that he would never vote for Trump, published a blog in 2019 titled “I Support the President” in a complete turnaround from his earlier stance. The Times pointed out that back in 2016 Erickson wrote that it was “no wonder that so many people with swastikas in their Twitter profile pics supported him. I will not vote for Donald Trump. Ever.” Senator Lindsey Graham and Brent Bozell, both NeverTrumpers in 2016, have since openly expressed their support for the president.

The Problem of Duplicitous Envy

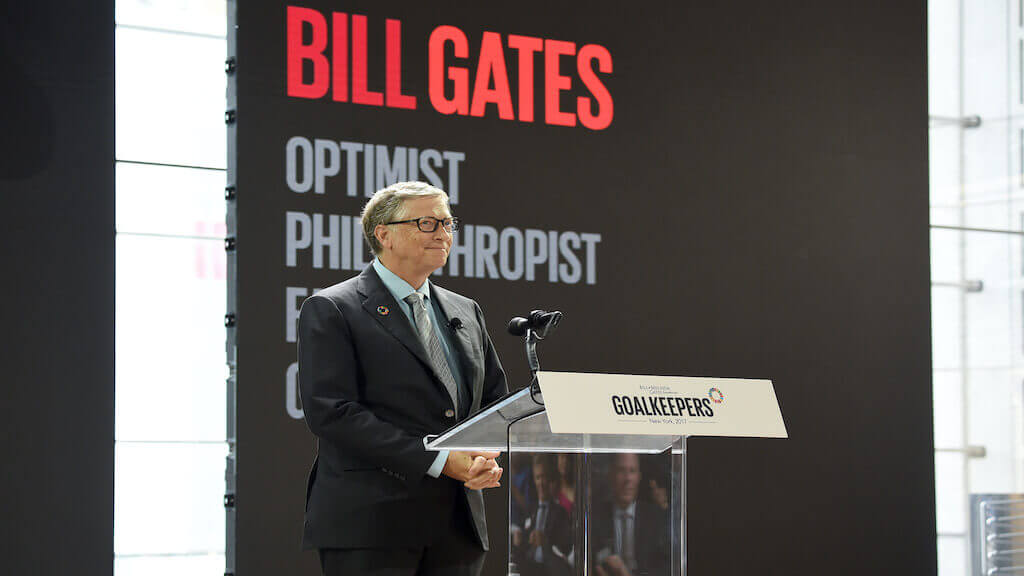

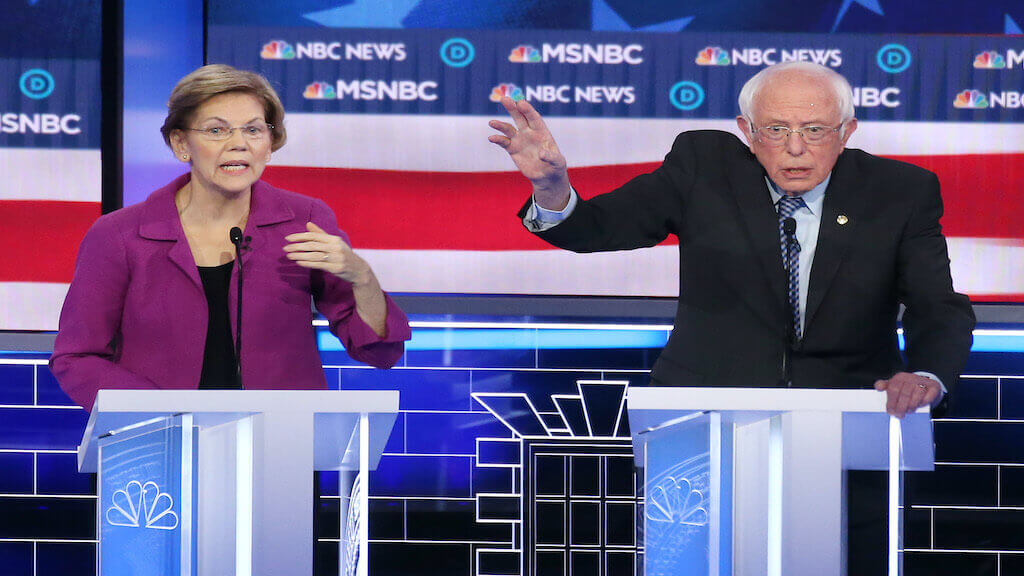

One of the problems that many progressive candidates for political office face is that in order to encourage voters to defame the rich, they need to hide their own wealth. This has become more difficult as the wealth of many progressive presidential candidates far surpasses that of conservatives. Forbes notes that failed Democratic presidential primary competitor Elizabeth Warren has a net worth of $12 million, lives in a $3 million Victorian home in Cambridge, and has an $800,000 condo in Washington, D.C..

Bernie Sanders, the millionaire democratic socialist candidate for the presidency for 2020 has his own embarrassment of riches. With three homes—including a $500,000 vacation home on Lake Champlain—Sanders and his wife, according to Forbes, have amassed a $2.5 million net worth from real estate, investments, government pensions, and earnings. A large portion of that wealth derived from the $200,000 “severance” package given to Sanders’ wife, Jane, when she was removed as president of Vermont’s debt-burdened Burlington College.

Indeed, during her seven-year tenure as president of the college, from 2004 to 2011, Jane Sanders pledged to double the student enrollment by spending millions of dollars of borrowed money on a beautiful new campus—33 acres along the bank of Lake Champlain that was purchased from the Roman Catholic Diocese of Burlington. Mrs. Sanders predicted that the new campus would surely attract more students and donations from alumni. It didn’t. The next year, Sanders took her severance package and left Burlington College in such dire straits that by July 2014, the New England Association of Schools and Colleges (NEASC) put the institution on probation for not meeting its financial resources standard. The Chronicle of Higher Education concluded that since the U.S. Department of Education allows a college only two years of probation, Burlington College would have lost its accreditation in 2017. On May 13, 2016, the Burlington College Board of Trustees voted to close the college.

Jane Sanders promised that “other people’s money” would keep her school afloat. It didn’t. Now Burlington College is facing allegations of loan fraud during Sanders’ tenure as the school’s president. Coralee A. Holm, the college’s dean of operations and advancement, released a statement claiming that the institution had struggled under a crushing weight of the debt that Sanders had amassed during her tenure related to the $10 million purchase of property from the Catholic diocese. Though the purchase of the property is certainly not evidence of socialism, the way Sanders was able to gain approval for the loan from the Vermont Educational and Health Buildings Financing Agency raises questions that are still unanswered.

In a lawsuit on behalf of parishioners in the Burlington Diocese, the complaint claims that “the loan transaction involved the overstatement and misrepresentation” of nearly $2 million in what were purported to be confirmed contributions and grants to the college. The loans were contingent on the college’s providing proof of a minimum commitment of $2.27 million in grants and donations prior to the closing. Sanders never had the confirmed grants and donations she claimed she had, and instead, the complaint alleged, she “engaged in a fraudulent scheme to actively conceal and misrepresent material facts from a federal financial institution.” She left the presidency later that year, and the college defaulted on its loan from the diocese. The agreement was costly for the diocese, which was forced to accept payments totaling $1,592,000 and an unsecured $1 million investment as settlement of the $3.65 million in principal it was owed. The diocese was also forced to forgo collection of up to $923,000 in interest accrued over the five-year life of the loan.

Questions remain about how Jane Sanders was able to convince creditors—including the Catholic diocese, the state financing agency, and a federally insured bank—that the school qualified for the $10 million loan. The complaint filed by the “aggrieved Vermont parishioners” suggests that Sanders’s privileged status as the wife of a powerful United States senator “inoculated her from the robust underwriting that would have uncovered the fraudulent donation claims she made.” The public harm, in this case, is substantial and should be viewed as an example of crony capitalism, but it is unlikely that will be the case. Regardless, it is instructive to look at this scandal as yet another example of the fraud of socialism itself. The insolvency of Burlington College brings to mind the famous quotation from Britain’s legendary Conservative prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, that the real problem with socialists is that “they always run out of other people’s money.”

A key theme of the presidential campaign of Vermont socialist Bernie Sanders was his pledge to make tuition at public colleges “free,” but he promised to tax Wall Street investors to pay for his $75 billion-a-year program.

Societies flourish when people find ways to control envy, this most destructive emotion. Because envy is ever-present—and powerful when aroused—a society’s ability to achieve greatness depends on its ability to control this highly destructive emotion. But, as wealth grows, inequality grows with it, and there is always the seductive appeal of revengeful revolution.