Although debates over the meaning of patriotism in a democracy date to Demosthenes warning ancient Greeks about their civic complacence, in America the phrase “my country, right or wrong” dates to a specific, alcohol-fueled dinner in 1816 in the Virginia naval town of Norfolk.

The dignitaries present were celebrating a military victory by the U.S. Navy off the Barbary Coast. The first toast that night paid homage to a poem penned two years earlier in Baltimore celebrating another naval battle: “The Star-Spangled Banner—Long may it wave/ O’er the land of the free/ And the home of the brave.” As the wine flowed freely, the hero of the hour—“the Conqueror of the Barbary Pirates,” the newspapers called him—arose to give his toast: “Our country,” said Commodore Stephen Decatur. “In her intercourse with foreign nations may she always be in the right, and always successful, right or wrong.”

Widely reprinted at the time, Decatur’s conditional hope that America would occupy the moral high ground was eventually distilled to the more jingoistic “My country, right or wrong!” That is one notion of patriotism. There are many others. Defining love of country has long been a sensitive topic, and in the highly polarized current political environment it has a distinctly partisan cast. Patriotism is also understood differently along racial and gender lines. Today it exists upon stark generational fault lines as well.

In the period between Juneteenth and July 4, RealClear Opinion Research delved into these waters. Specifically, the survey of 1,762 registered voters was conducted June 21-24. Its findings are instructive for the leaders of America’s two dominant political parties, as well as for any citizen concerned about where this nation is heading.

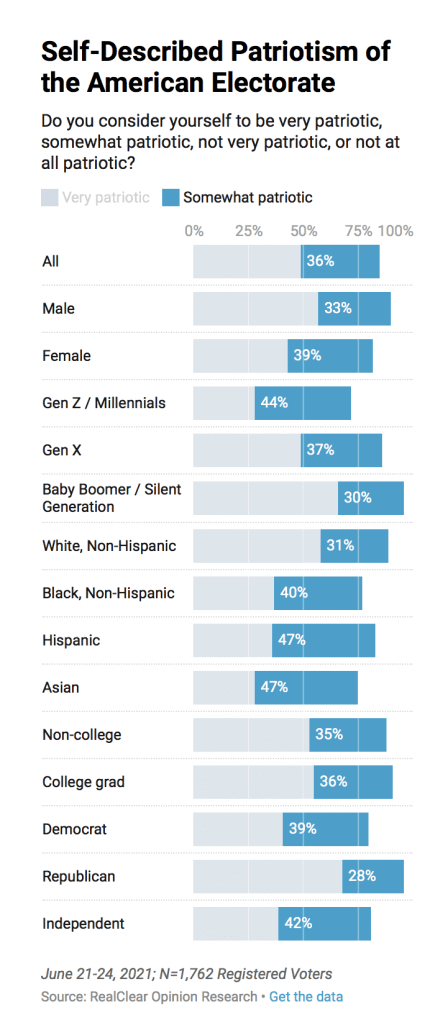

For starters, fully 85 percent of Americans consider themselves patriotic. Demosthenes would have approved, but what that implies in word and deed varies greatly. As such, we don’t all feel the same way. One example: 57 percent of male voters in this country consider themselves “very patriotic,” compared to 43 percent of women. The overall number of whites who describe themselves as very patriotic is significantly higher (58 percent) than for African Americans (37 percent), Hispanics (36 percent), or (Asian Americans 28 percent). Republicans (68 percent) are much more willing to describe themselves this way than Democrats or independents, both of whom are around 40 percent.

For Republicans who watch Fox News, this number is even higher (74 percent for Fox News Republicans compared to 58 percent of other Republicans). There is an income gap in professed patriotism, too, although little difference by education levels among whites. Yet the survey also revealed that in the past year a vast majority of voters engaged in a range of activities that most Americans consider expressions of their patriotism—and that with some of these, there is little partisan difference. These range from wearing a mask to prevent the spread of COVID-19 (91 percent) to voting in national elections (88 percent).

Two-thirds of respondents said during the previous year they had thanked a veteran or member of the U.S. armed forces for their service and two-thirds also received their COVID vaccine. And while there are partisan breakdowns in those responses (more Republicans paid their respects to veterans while more Democrats got their shots) the more interesting finding is that Americans recognize a wide array of measures as patriotic. And they do so even for gestures they themselves do not take. For instance, only 48 percent of voters flew an American flag last year, but 76 percent acknowledge that flying the flag is patriotic. Likewise, while only 34 percent said they participated in community service last year, 63 percent consider volunteering an expression of love of country.

“The modern interpretation of patriotism is as diverse as the country the flag represents,” said John Della Volpe, director of polling for RealClear Opinion Research. “It is not owned by one party or platform. We found that at least three in four members of every major subgroup of American voters profess love for their country—and tens of millions of Democrats, Republicans and independent voters are regularly engaged in activities that exhibit their respect for the country and for those who sacrifice to serve and make it better.”

Della Volpe, who also directs polling for Harvard University’s Institute of Politics, has delved deeply into Americans’ views of themselves and their own political system for RealClearPolitics since his October 2018 poll revealed the existence of five distinct political “tribes.”

That survey, done near the halfway point of the Trump presidency, is in some ways a bookend to the current study. In that first poll, respondents were queried about their feelings regarding a series of images ranging from U.S. Marines in combat and an American flag on the side of a barn to photographs of an interracial couple and black football players kneeling during “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

A similar method was employed in this latest survey: Respondents were shown a series of 17 images (13 of scenes from American life and four of specific politicians) and asked to rank how much that image represented “what is right about America.” With only three exceptions, there were double-digit differences between Republicans and Democrats. This is understandable when it comes to political figures such as Joe Biden and Donald Trump. But it’s somewhat disconcerting to learn that 53 percent of Republicans think a photo of Yom Kippur worshipers expresses something good about America, while only 44 percent of Democrats feel the same way. When it came to an image of a Christian church, the gap was even more glaring—much more so. Three-fourths of Republicans reacted positively to the church picture, while only 44 percent of Democrats did so. (For independents it was 53 percent).

Other dichotomies included a photo depicting U.S. military personnel doing global humanitarian work (78 percent Republicans, 59 percent Democrats, 63 percent independents). Or a simple photo of the U.S. flag on a barn (80 percent Republicans, 52 percent Democrats, 58 percent independents.) To put it simply, judging by traditional measures of patriotism, Republicans score higher. But the modern Democratic Party is younger, more female, more ethnically diverse, and more attuned to the values and priorities of the LGBT movement. This emerging Democratic majority ranked a picture of a swearing-in ceremony for new immigrants higher than Republicans (46 percent-34 percent) as well as for a Chinese New Year Parade, which Democrats approved by a 2-to-1 margin over Republicans. Only 37 percent of Democrats view a depiction of Wall Street in favorable patriotic terms, compared to 52 percent of Republicans.

The coronavirus pandemic continues to be an issue that divides us. Fully 72 percent of Democrats ranked a depiction of a COVID vaccine as pro-American—much higher than either Republicans or independents. One of the largest gaps was for a picture of a Black Lives Matter protest march honoring George Floyd: 46 percent of Democrats approved of this image, while only 16 percent of Republicans did so. Given the rhetoric among political elites and in the mainstream media, this 46 percent figure seems low. Likewise, despite the media attention given to transexual rights, only 33 percent of Democrats responded positively to an image of a transgender flag—not too much higher than Republicans (29 percent) and independents (27 percent).

For those who value lowering the temperature on discussions about the meaning of patriotism, the best news out of the section of the poll dealing with images was that only 14 percent of Americans thought a picture of the January 6 riots at the U.S. Capitol was a positive—including fewer than one in five Republicans.

The Prism of Race

Another intriguing finding concerned voters’ reactions to critical race theory. Although this subject has galvanized conservative media and Republican politicians, the public apparently is far less convinced that it constitutes a threat to national cohesiveness.

For one thing, a majority of Americans don’t know much about CRT—and, for that matter, are unfamiliar with the New York Times’ controversial “1619 Project” and the concept of American exceptionalism. Only 43 percent of voters expressed familiarity with critical race theory, a number that didn’t vary much by age or race—although suburbanites and college-educated respondents knew more about it than rural voters or those without college degrees. (Not surprisingly, given the amount of airtime it has received, Republicans who watch Fox News are much more likely than Republicans who do not regularly watch Fox to know about CRT.)

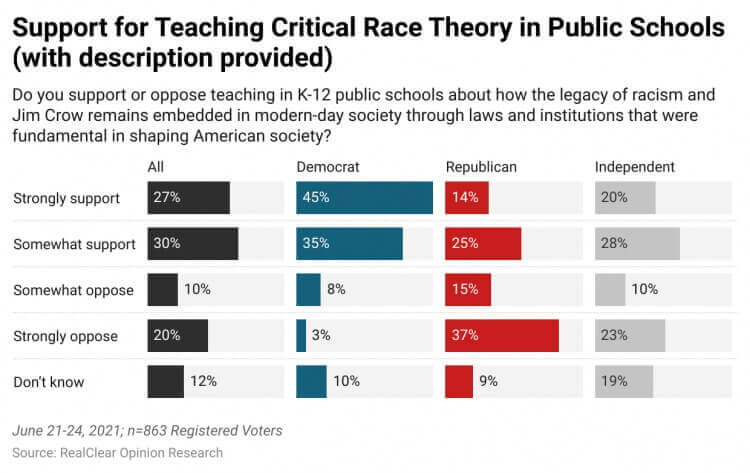

Yet most respondents did not tend to recoil from the term in disgust. When asked whether they support CRT or not—without any background information provided—42 percent expressed support, compared to 36 percent in opposition, with 22 percent expressing no opinion. When it was defined for them in the survey, the backing for the concept actually rose.

Here was that definition: “Do you support or oppose teaching in K-12 public schools about how the legacy of racism and Jim Crow remains embedded in modern-day society through laws and institutions that were fundamental in shaping American society?” And here were the responses:

SocialSphere/RCP

Progressives will feel good about those numbers. But conservatives can cheer themselves with this thought: As Independence Day approaches, the RealClear Opinion Research survey also shows that American exceptionalism is alive and well in the hearts of most voters. Nine out of 10 respondents believe that the United States continues to do a lot of good in the world. And while only 32 percent of voters today assert—as almost all of the Greatest Generation believed—that “America is exceptional, it is the moral leader of the world,” only 10 percent agree with the statement “America does more harm than good in the world.”

In other words, we do good, but we should aspire to do better. This is really what Commodore Decatur was saying in Norfolk 205 years ago. And it’s what U.S. Senator Carl Schurz said more directly while paraphrasing and improving upon Decatur’s toast in 1873 during a fiery Senate debate. Schurz was Prussian immigrant whom Wisconsin Senator Matthew Carpenter accused, in so many words, of putting foreign interests ahead of our own during a legislative fight over selling surplus weapons to France. You see, even back then we argued about patriotism—not to mention the issues of immigration, arm sales, and gun control. But Schurz had been a friend of Abraham Lincoln, an ardent abolitionist, and an early Republican who made political speeches (often in German) to turn out immigrant voters for Lincoln. He’d also served in the Union Army with distinction during the Civil War, commanding troops at Second Bull Run, Chancellorsville, and Gettysburg—and he spoke English as well as he did German.

He responded to Senator Carpenter that he would match his record of service to America with anyone before adding this: “The senator from Wisconsin cannot frighten me by exclaiming, ‘My country, right or wrong.’ In one sense I say so too. My country; and my country is the great American Republic. My country, right or wrong: if right, to be kept right; and if wrong, to be set right.”

Editor’s note: This essay appeared originally at Real Clear Politics.