The New York Times on May 6 published a full-dress condemnation of Facebook’s decision merely to continue suspending Donald Trump from its platform. The Times said that “our democracy” demands shielding voters and their representatives from what it considers falsehood concerning the 2020 presidential election. Rather than trying to show that any particular statement was false, or demonstrating the truth in opposition to Trump, the Times merely pointed out that his “lies” were dangerous because the majority of state legislatures had already voted to impose restrictions on the practices that had made 2020’s electoral outcome possible.

Hence Trump and all other purveyors of “untrustworthy content” must be banned permanently. By the same token, any number of persons and entities involved in managing the 2020 election have refused to turn over their records to legislatures that want to audit them. Most recently, Maricopa County, Arizona apparently deleted a directory full of election databases before delivering to the Arizona legislature the equipment on which it was stored.

(Maricopa County Recorder Stephen Richer denies that’s what happened. A spokesman for the auditors says they alleged no malice aforethought on the part of the county; they merely asked for clarification. ”Maybe it was deleted because it was a duplicate of something that was elsewhere.”)

The bigger point is this: No law empowers the Times and Facebook, much less officials in Arizona, Georgia, Pennsylvania, Michigan, etc., to decide what is and is not properly part of public discourse about elections. The First Amendment argues against it. Yet they presume to censor. By what right?

On the instruction of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) and Senator Charles Schumer (D-N.Y.)—and without objection from Republican leaders—the Capitol Police department has refused to release any details about who killed Ashli Babbitt on January 6 in the Capitol. The suspicion is that this is because the killer may be a special agent on Pelosi’s protective detail, a black man who reportedly pledged allegiance to Black Lives Matter. By what right does anyone preclude discussing the possibility that a politically motivated murder may have occurred?

On May 9, the University of Massachusetts suspended three girls for having been mask-less. No matter that they were off-campus and outdoors, where even the Centers for Disease Control says they were at negligible risk themselves and posed no serious risk to others. They were not allowed to take final exams and forfeited the $16,000 tuition they paid for the semester. Again, no statute empowers. Ordinary contract law forbids such behavior. And yet . . . by what right was this done?

By a similar token, most universities have announced that students will need to show proof of vaccination in order to be admitted to campus in the fall, and wear masks to boot, regardless of whether they have had the virus, or of their personal preferences.

Note well that when the University of Massachusetts students—and all others as well—accepted admission to their respective institutions and paid their respective tuitions, they entered into mutually binding contracts. Neither any law nor contract empowers those institutions to impose the wearing of masks, never mind the introduction of drugs into their bodies.

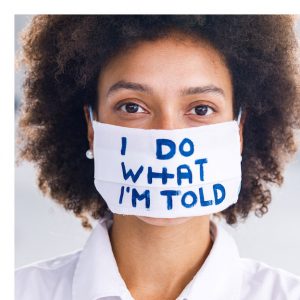

And yet on May 13 after the Centers for Disease Control had canceled the requirement that vaccinated persons wear masks—responding to a veritable revolt among American physicians and the general public, especially parents, against that requirement’s self-contradictory, absurd, irrelevance to public health—congressional Democrats, Democratic governors, major retailers, and airlines all pledged to maintain the requirement for people entering their premises.

The absence of law and relevance to public health notwithstanding. By what right?

An Absense of Consent

Questioning such claims of right is no mere rhetorical exercise. It points to the fundamental clash of regimes that is revolutionizing American life in our time. It is the clash between our ruling class’s assertion of the right to rule by its own discretion—which it calls “our democracy” and the democratic republic under which we had been living.

Our republic’s founders recognized a twofold test by which to judge whether an act of government is right. First, by the very act of revolting against the laws of King and Parliament, Americans asserted that laws are to be obeyed not because of who promulgates them but above all because they are right in and of themselves—right by nature. No one may rightfully command wrongdoing, like trying to do something naturally perverse, like turning another human into an animal by enslaving him or turning a man into a woman.

The second test follows from the basic fact of natural human equality: that laws must emanate from the will and consent of the majority. But for the effective sovereignty of the many to produce laws that are right in and of themselves, they must be able to distinguish between true and false, better and worse. And since our republic’s basic premise is that “all men are created equal,” they sort themselves into majorities and minorities on any given issue by persuading one another.

That is why the American republic has always forbidden any interference in the flow of the facts and opinions by which the many exercise their sovereignty. That very premise of equality also enshrines the integrity of private contracts. A contract is a done deal because it is among equals.

But denial of human equality, of right, wrong, and persuasion, is the essence of what the ruling class calls “our democracy.” The regime under which we live consists of persons, regardless of whether they sit in what is legally the public or private realm, who are related to one another intellectually, morally, professionally, socially, financially, politically, maritally, and extramaritally. They are interchangeable. They suppose themselves superior to the rest of us. As they impose their concurrent will on us, they reverse republicanism’s very premises.

The Interest of the Stronger

Whence does the New York Times or Facebook get the right to decide once and forevermore that certain facts and arguments are so “untrustworthy” that ordinary people cannot pass judgment on whether they are true or not? Answer: they don’t get it by persuading you because they do not acknowledge the existence of a tribunal of truth, or that confronting contrary claims is the only path to truth. For such as they, the substance of right is neither adherence to nature nor to popular consensus but merely the power to make one’s assertion stick. Just as Plato’s Thrasymachus stated 2500 years ago, “Right is the interest of the stronger.” They get their right to power from each other as they join together in browbeating you.

That is why the restriction of information to that which is useful to the powerful few is as indispensable to what they call “our democracy” (and that the ancients called oligarchy) as the free circulation thereof is to republican government. The oligarchs already know all they need to know about right and wrong: right is what tends to foster their own power, and wrong is whatever might threaten it. Hence, oligarchies reduce public discourse to “narratives” approved or not according to whose interests they serve and when.

Between January and May, the oligarchy judged it essential to keep schools closed, to mandate masks, to hype the threat of white supremacy, and to suppress evidence of a political murder in the U.S. Capitol. No one should be surprised that as its priorities change, old narratives are thrown under the proverbial bus, and new ones imposed.

In what our oligarchs call “our democracy,” no interest is common to the powerful few and the powerless many. This is because, from their point of view, differences in power between human beings are as great as the differences between the human species and the other animals. Just as equality is republicanism’s bedrock—and hence contracts are as binding within it as are laws, so inequality of power is oligarchy’s essence. That is why lawlessness is oligarchy’s rule as regards contracts as it is regarding laws.

Within oligarchy, all is fluid.

That is why America’s republican many should be clear that the oligarchy’s structures and potentates offer no safety whatever. Surrender to today’s oligarchic priorities augurs no peace for tomorrow.

The many’s prospect of recovering a modicum of republican right lies in clearly, wholly, denying the legitimacy of oligarchic claims to power and privilege and insisting on the exclusive authority of republican law and private contracts. The oligarchy’s power over republican institutions ensures that such insistence will require substantial challenges, including civil disobedience. That, in turn, puts a premium on leadership.

But that is another story.