In Live Not By Lies: A Manual For Christian Dissent, Rod Dreher has provided an excellent update to his 2017 best-seller, The Benedict Option: A Strategy for Christians in a Post-Christian Nation, detailing harrowing stories of Christians (i.e. Catholics, Protestants, and Eastern Orthodox) and their heroic tales of dissidence, perseverance, and faith while living under Soviet totalitarian rule. He plucks insights from their accounts and considers them in the shadow of the soft totalitarianism now growing to supremacy in the West. Both books consider the matter of Christian life in a post-Christian world. How do we keep the faith when all about us is unfaithful? When we no longer enjoy any political agency or heft? What is our responsibility to a world that is embarrassed by us or even hates us? Of course, these questions were answered once and for all time by the Word made flesh. Where particulars are concerned, Dreher looks to the past for answers, in and beyond Scripture.

In The Benedict Option, Dreher looks primarily to the monastic code of Saint Benedict and to the example set today by its adherents for a Christian way forward. He calls for the continued restoration of our Church communities and our recommitment to the cultivation of the Faith on the margins of a godless, hedonistic society, itself some co-mixture of the worst characteristics of the dystopias in Huxley’s Brave New World and in Orwell’s 1984. Accordingly, we—like Saint Benedict who helped saved civilization and Christianity during the fall of the Roman Empire by creating remote cells where disciplined believers, living in community, kept the ancient flame alive—must practice our faith without fear in the company of tight-knit groups, cells, and enclaves, and must do so or imperil the souls of all mankind.

In Live Not By Lies, Dreher points to the urgent need for Christians to emulate the courage and stratagems of their dissident family behind the Solidarity Movement in Poland, the Velvet Revolution in Czechoslovakia, and other historic defeats of leftist totalitarian regimes. His insights are extremely valuable and they provide a detailed roadmap for keeping the light of civilization alive as well as the Truth upon which it is and will forever be contingent.

Unlike their brethren persecuted and savaged daily in Communist-occupied China, Christians in the West ought to prepare themselves to deal with life under soft totalitarianism; under what Dreher calls the Pink Police State. The varieties of leftism that Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn traces in his remarkable history tying the French Revolution to the killing fields of Cambodia—a history nicely complemented by Dr. Stephen R.C. Hicks in Explaining Post-Modernism—have corrupted (in ways both Marcusian and Alinskinian) the majority of Western institutions, whether they be political, social, or educational. They with their statist peers have seized the corridors of power. Together, these leftists have taken considerably more ground in the hearts and minds of Americans by trading comfort for liberty, and by using their technology and reach to socially engineer Christianity out of American life. The result is an un-free but comfortable populace, choking on lies and averse to responsibility.

Though the matter is dire, Dreher makes a strong case for hope and details proven best practices in Live Not By Lies. Ultimately, the way forward is unchanged: to follow Christ with love and humility; to live as exemplars and, if it comes to it, to die as martyrs. Without political gravity or any significant hold on the corridors of power here or elsewhere, we must commit to practicing what Czech dissident Václav Havel called anti-political politics: “politics not as an art of manipulation or rule over others, but as a way of achieving meaningful lives together, politics as ‘practical morality, as service to the truth, as essentially human and humanly measured care for our fellow humans.’” Part of the hope is that if we live the kind of meaningful lives dedicated to God that we are so fond of discussing, we’ll not only keep the Faith alive but also evangelize by example—convert this world and its temporary masters by living not by lies (a way of living Solzhenitsyn implored all men and women of conscience to take up), but by Truth.

To live not by lies is to refuse to allow oneself to become a puppet or a vessel for the Pink Police State or any other soulless regime—to live faithfully and practice within cells composed of other Christians. In both books, the idea ultimately is to weather the storm; to one day restore civilization as the monks in Norcia and Iona had; and, after organizing and gaining steam, repelling the evil empire as Christians had in the East over the course of the 20th century.

How long can we survive on the fringes this time around when so much has changed? Though the variety of totalitarianism we face is “soft,” the technology and power that statists with no love lost for Christians now employ is actually total. And what happens when the CCP hardens that totalitarianism worldwide?

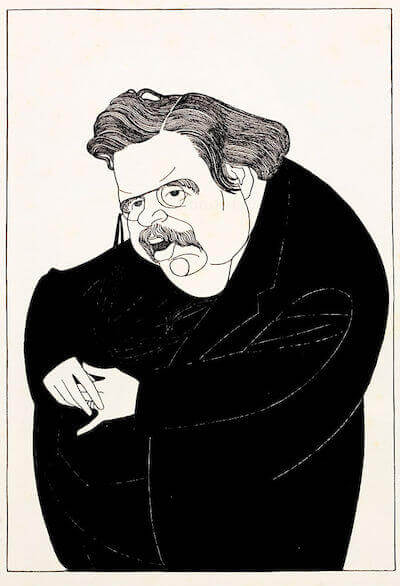

The trouble, therefore, is compounded by the fact that the Church will not only have to survive the reign of what Dreher calls the Pink Police State, but the Chinese Communists’ Hundred-Year Marathon as well. It’s not simply a matter of regrouping and regrowing the Faith in America until the nation comes to its senses (which I believe the conversion of Jordan Peterson and other leading intellectuals like him may help with, echoing major conversions like John Henry Newman, Robert Hugh Benson, C.S. Lewis, and G.K. Chesterton). The CCP intends to become the predominant world power by 2049. Graham Allison and other apologists for America’s genuflection to the new world power see Chinese Communist supremacy as inevitable. If the West has not presently the stomach and the distinction to save itself, then what hope will it have 28 years from now when the hard totalitarian state eclipses our soft totalitarian state? If politics is downstream from culture, and Dreher is right in reasserting the claim that we’ve lost the culture war, then what hope do we have of executing the Benedict Option when religious liberty is totally annihilated and the CCP leaves no quarter for believers? After all, the statist anti-god is a jealous anti-god.

If we do not exhaust all just options available to us, we risk having the Truth and Light being forgotten or hidden in much of the world. What great tragedy: to lose the final battle in a war already won on our behalf. The Benedict Option is no doubt part of the solution, but is there another we should also attempt? If there were a massively popular movement, informed by the Christian imaginary and therefore common sense but not yet formally Christian, would it be prudent to attempt to convert it? Those committed to “anti-political politics” can continue in that way, but is there any harm in others taking up the challenge? To appeal to our compatriots with common sense and then remind them that common sense is Christian?

We have certainly lost the culture war, though that result is not permanently fixed. After all, much of Dreher’s insights and proposals speak to turning the tide over time. It may be a fault of the culture and fuzzy thinking that have taken us to this place, but I do not think that we have the luxury of time and I certainly do not think we can abdicate our responsibility to all those souls who will be lost in the interim. There lies in conservative populism a great opportunity, not just to turn the tide sooner rather than later, but to restore that foundational element that America cannot do without.

Before pressing onto the matter of the Chesterton Option, let me be extremely clear: first, the nature of the crusade I will soon be discussing is not kinetic; that is, it is not a matter for force and violence. The definition for a crusade here is: “A concerted effort or vigorous movement for a cause or against an abuse.” The effort in question pertains both to spiritual and cultural warfare; to saving souls and winning with ideas. The second point of clarification: I am not arguing that Dreher is hopeless or that he’s discounted the possibility of a great awakening. That is to say, I have no doubt he’s considered this route. In fact, based on his examination of the medieval Christian imaginary contra the modern imaginary and his scrutiny of the place of God in our lives today versus the place of God in the life of Aquinas, it’s clear that at some point he was looking for parallels; mining for insights into how to trigger a spiritual or cultural crusade. A large part of Aristocratic Europe did, after all, abandon wealth and luxury to execute God’s Will in deserts far away and unkind.

The difference is, and this difference Dreher emphasized in The Benedict Option, is that conceptually, God no longer is the binder holding all things together in the minds of the majority. If He exists, it’s remotely as the deists hold, or inhumanly as the Arians and their major heretical offshoots hold. So, it seems just as the Earth no longer sits at the center of the universe, where the West is concerned, Christ no longer sits as judge and guardian at the center of our lives. It would be hard, therefore, to stir up the masses to execute some variant of the Benedict Option on a national scale. Hard, but not impossible.

Consider, for a moment, the MAGA movement. Conservative populism is a reaction to: the cemented uniparty in Washington; the failure of the Republican Party to stand up for Christian values; America’s unaccountable technocracy; the leftist zealots on campus; never-ending wars; corporatism, neoliberalism, and globalism; the attack on the family and the institution of marriage; the widescale murder of the unborn; radical Islam and radical Marxism both; and a host of other predacious modes of thought, action, and being that have corrupted American institutions and relations. It is a movement informed by common sense and populated by common people. In this regard, there is an uncanny parallel between conservative populism and another civilization-saving popular movement. G.K. Chesterton pointed out that the First Crusade was:

A popular movement . . . not a thing which the populace followed; it was actually a thing which the populace led. It was not only essentially a revolution, but it was the only revolution I know of in which the masses began by acting alone, and practically without any support from any of the classes. When they had acted, the classes came in; and it is perfectly true, and indeed only natural, that the masses alone failed where the two together succeeded. But it was the uneducated who educated the educated . . . In the First Crusade it was the ordinary man who was right or wrong. He came out in a fury at the insult to his own little images or private prayers, as if he had come out to fight with his own domestic poker or private carving-knife. He was not armed with new weapons of wit and logic served round from the arsenal of an academy. There was any amount of wit and logic in the academies of the Middle Ages; but the typical leader of the Crusade was not Abélard or Aquinas but Peter the Hermit, who can hardly be called even a popular leader, but rather a popular flag. And it was his army, or rather his enormous rabble, that first marched across the world to die for the deliverance of Jerusalem.

Though for all intents and purposes the MAGA movement’s aims are presently secular, it is ultimately Chestertonian in its thinking, and anything Chestertonian is ripe for conversion.

Of course, Dreher detests Trump and dismisses populism as another side effect of the nation’s waning religiosity—some noise and involuntary spasms in the final days of Christendom’s breakdown. It is a great error to discount the inherent Christianity of conservative populism when discounting the morality of Trump, and even discounting the latter is a role reserved only for the Judge. What’s abundantly clear, however, is that that a pugnacious and crude real estate magnate who became president, did so in large part due to his Christian messaging and his anchoring in Judeo Christian imagery. Dreher believed this to be opportunism.

Sometimes opportunism consists in saying things you don’t believe to get ahead. In Trump’s case, I think here it was a matter of him saying things he believes but had in some ways neglected. The fact is he said the right things and then took the right action accordingly; particularly around decisions concerning life, religious liberty, and the importance of the local; in addressing the danger of big government, big corporations, the CCP, and identity politics; and in emphasizing the importance of the family and sacredness of life.

President Trump no doubt is imperfect just as the supermajority of Christians similarly is imperfect. In fact, Steve Bannon, who knows the president well, routinely refers to 45 as an “imperfect instrument.” Yet, we’ve seen imperfect instruments wielded to protect Christianity before. (Don Juan of Austria comes to mind.) This particular imperfect instrument, equally brazen and rough around the edges, just happened to do more for Christians in America than Romney, the Bushes, and perhaps even Reagan ever hoped to do. His 1776 Project, for instance—obfuscated by the Biden regime—is a testament to his sense in this regard, predicated on Tocqueville and Adams’ own, that democracy cannot survive the loss of the Christian faith. Whether or not Trump continues to lead the conservative populist movement is irrelevant. The fact is that he started it, tethered a pseudo-Christian worldview to it, and in so doing, provided us with another option: the Chesterton Option; not an alternative, but something extra to the Benedict Option to attempt before the world is fully shrouded in darkness.

During the French Wars of Religion, Henry IV claimed that Paris was worth a Mass. If that’s the case, then America is certainly worth a crusade.

The conservative populist movement presents a worldview antithetical to the positions held by the Pink Police State and the Chinese Communist Party. I am not so deluded to think that this movement alone will save or preserve the American soul, but it will at the very least ensure that soft totalitarianism doesn’t harden, and that religious liberty may not be wholly undone. The Chesterton Option is just the combative populist way of securing the legal, political, and cultural wiggle room for the Benedict Option’s execution; of building on the common sense of the common man so loathed by statists and leftists alike.

Dale Ahlquist and Joseph Pearce’s biographies of G.K. Chesterton are helpful when trying to understand the Apostle of Common Sense and what made him special, even saintly. For our purposes here, it’s worth noting that Chesterton did a great job of loving his enemies, speaking truthfully, and pointing out, particularly in The Everlasting Man, that the so-called strangest story in the world also happens to be the greatest story in the world; that only in Christianity where the highest myth meets with the highest reality, does man become something more than exploitable, exhaustible putty for temporal powers; that only one culture has a cult at its center that is true. If we are to win the culture war, we have to return to and extol that which is true, and live accordingly—and yes, that means factoring it into our political mission.

The kind of political crusaders this Chestertonian movement needs are the very same who’ve been drawn to it: people unapologetic about their love for Christ, their support for life, their antipathy for leftism, and their affinity for unobtrusive government accountable to the people. Dreher remarks in The Benedict Option: “Western society is post-Christian and . . .absent a miracle, there is no hope of reversing this condition in the foreseeable future.” If these politicians and the members of the relatively amorphous conservative populist movement are willing to make this a Chestertonian movement and therefore a Christian movement—to save this once-Christian nation—then you might be looking at the first of many miracles necessary to turn the culture war around, God willing.

Dreher nevertheless is right about that which this movement, if formally Christian, must avoid. It must rebuke the “inordinate individualism, materialism,” and tyrannical impulses that are now ubiquitous in American life and politics. It must remember that liberty and religion work together and support each other, and that without the latter, the former is meaningless. This point Alexis de Tocqueville made clear:

Religion sees in civic liberty a noble exercise of man’s faculties, and in the political realm a field given by the Creator to man’s intelligence . . . Liberty sees in religion the handmaiden of its struggles and triumphs, the cradle of its infancy, the divine source of its rights. She sees religion as the safeguard of morality, and morality as the guarantee of the laws and of its own posterity.

The movement must remind those receptive amongst the American populace—especially those who appreciate the cultural and legal implications without accepting the supernatural basis—that all men and women are made in the image of God. The comprehension of imago Dei is an antidote to what Saint Pope John Paul II referred to as the culture of death—to the ritual sacrifice of the weak, the infirm, and the unborn. (Whereas Carthage burned its children alive for Moloch, America kills its own for convenience and comfort.) In addition to upholding the sanctity of life and the sacramental nature of marriage, a formally Christian populist must promote: responsibility and accountability; the use of freedom to live virtuously; the importance of the family; the value of truth; the necessity of debate and the danger of quarrel; the goodness of creation; the sacredness inherent in all people; and the fallen state of man. Above all, while ending the trend of standardizations by low standards, it must employ that common sense inspired by the Truth incarnate.

The Chesterton Option is not a means to save every American soul. Politics, to Dreher’s point, cannot ultimately redeem a fallen world. Only Christ can. The purpose of this cultural crusade to be executed by conservative populists is to save America so that we have the basic liberty and headroom to make the Benedict Option. It is only by rediscovering and elevating our Christian culture that we can differentiate ourselves from the new evil empire rapidly growing in the East on the backs of slaves; that we can find the moral courage to at once repel the Pink Police State here and Red China abroad.

If, as Dreher submits, our soft totalitarian state will make it harder and harder to practice our faith—if our technocracy will make it easier and easier for leftist engineers to police the minds of men—then we must do everything in our capacity, extra to the Benedict Option and living not by lies, to make room for God in the minds, hearts, and lives of our brethren and ourselves. Let us launch one last glorious push to save the world before kicking free the dust from our sandals. If we fail, then we’ll have lost valiantly in the final battle of a war that has already been won for us by the Redeemer. If we succeed, then the world will be better for it and leftist forces will be diminished, at least until Christians once again forget themselves, and we’re forced to let the scales fall from our eyes and the shackles from our wrists once again.