A Johns Hopkins study claiming that COVID-19 deaths are vastly overstated made the rounds recently on social media and alternative news websites—until the university retracted it. The work in question may still be found on the Wayback Machine. Researchers measured total U.S. deaths from all causes during 2020 and concluded that these deaths were not greater than deaths in previous years.

Skeptics were quick to pounce. For example, in this report, an alternative content provider led with the headline “Study: Absolutely NO excess deaths from COVID-19.” Then when Johns Hopkins pulled down the study, the plot thickened. A typical reaction: “Johns Hopkins Publishes Study Saying COVID-19 Deaths Overblown, Then Deletes It.”

When university took the study down, the Johns Hopkins News-Letter published an explanation that only clarified some of the issues raised by the study. To the main point—that deaths from all causes in the United States are not higher in 2020 than in previous years—the editors wrote “This claim is incorrect . . . according to the CDC, there have been almost 300,000 excess deaths due to COVID-19.”

But Johns Hopkins did not explain, or even speculate, as to where Genevieve Briand, the presenter of the retracted numbers, got her data. But there’s a fairly likely explanation, because this isn’t the first time something like this has happened this year.

In July, a meme went viral claiming, ironically, that “COVID-19 Cured Pneumonia.” As I noted in my investigation of the meme, the data the meme’s creators used came from “CDC Reported U.S. Pneumonia Deaths 2019-20” through March 25. They showed these deaths on a graph where the line representing current year pneumonia deaths was clearly well below the lines showing prior year pneumonia deaths. Ergo, the CDC was reclassifying pneumonia deaths as COVID-18 deaths to inflate the COVID death statistics.

Except the CDC probably wasn’t doing that—or, if it was, the shift was not nearly to the extent the meme inferred. What the author of that meme did, and apparently what Briand did as well, was fail to take into account the 10-week lag between when deaths are first reported for a given week, and when all the deaths that week are finally collected and tabulated. Typically, only about 25 percent to 30 percent of deaths in any given week are logged and reported by the CDC in the immediate following week. Only after eight to 10 weeks are 95 percent of deaths (or more) in any given week reported and known.

This means that for any given point in time, a graph where the CDC’s current year data is superimposed against prior year data will only show an accurate comparison if you ignore the most recent 10 weeks of current-year data. Those weeks will always show a downward curve because all the data for those recent weeks have not yet been received by the CDC.

Briand did have a useful insight, however, by focusing only on “deaths from all causes.” This eliminates the question of misclassification and merely asks whether or not more people are dying this year than in previous years. The CDC issues reports weekly, and each time they arrive in downloadable spreadsheet format, showing how many people died, per week, for every week preceding the week of the report. (Here, for example, is a link to the CDC’s weekly report for the week ended November 24.)

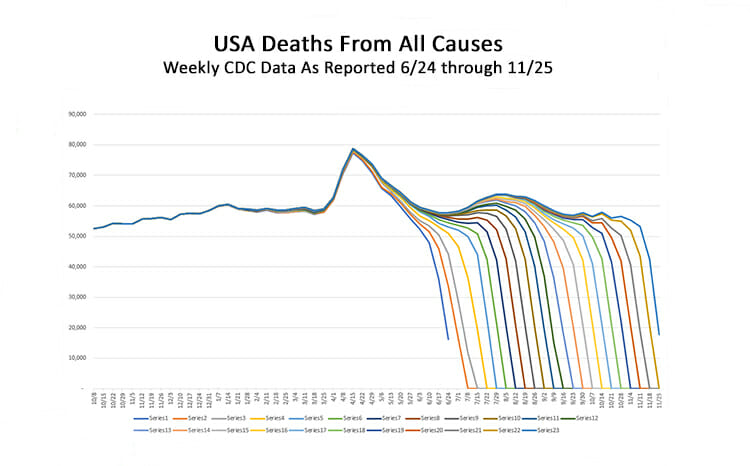

The graph below shows CDC data on U.S. deaths from all causes for this year. It depicts the data from 23 weekly reports from the CDC, starting on week 25 (the week ending June 24) through week 47 (the week ending November 24). Each report is one line on the graph. The vertical axis represents the number of deaths, the horizontal axis represents weeks in 2020.

Note how each week of data plummets toward zero as it plots the more recent weekly total deaths. Note, too, how the earlier weeks, where all data have been collected, show these lines all converging. This shows graphically how the CDC’s weekly reports do not provide complete totals for the weeks immediately preceding each of their reports. Only the data eight to 10 weeks behind any CDC weekly report are a reliable indicator of how many people actually died.

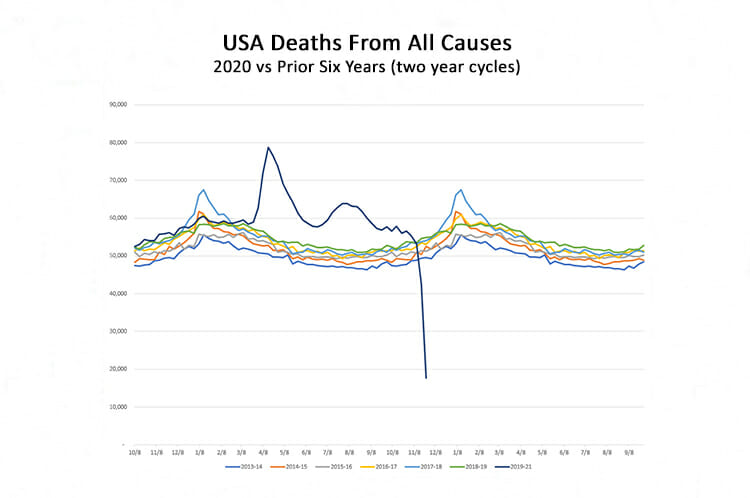

Knowing this, we can reliably compare weekly deaths from all causes in the United States in 2020 to the averages for those same weeks in previous years. The next graph does this, but uses a two-year horizontal axis to allow a clear visual representation of the historic cycle in previous years, where deaths go up in the winter and go down in the summer. To make this clear, the horizontal axis starts on October 1, which is the beginning of flu season, then tracks 104 weekly data points, representing two flu seasons over two full years. The choice of two years is also helpful to track COVID-19’s impact, since it did not follow the typical trajectory where deaths peaked in winter.

We can see there are six years of prior year data that track in close formation. The 2017-2018 flu season stands out as the most severe, with deaths peaking in January at nearly 70,000 per week. Overall, during the peak weeks of flu season over the six years prior to 2020, total deaths in the United States rose to not quite 60,000 per week, then dropped in midsummer to around 50,000 per week. That is the normal progression.

Against that backdrop, the dark blue line, which represents total deaths from all causes in 2020, offers a very different curve. Flu season was normal, with deaths topping out around 60,000 per week for several weeks in January and February. But then deaths spiked dramatically in March and April, during a time when deaths from all causes typically start to cycle downward slightly. The sharp peak in April clearly shows that something very alarming was happening, with the week of April 15 peaking at 78,821 deaths, around 15,000 deaths (or 46 percent) higher than what would have been typical for that week.

Further review of the graph shows what was referred to as the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, when total deaths peaked again at 63,867 on the week of July 29, roughly 12,000 deaths (or 23 percent) higher than what would have been typical in the middle of the summer.

But here’s where it gets interesting: Based on the CDC’s data time lag, an accurate curve for 2020 can only be plotted through mid-September. The numbers already reported show deaths from all causes still well above the previous six years, but it is too soon to know if they will continue to rise or not. That is where we stand right now.

The question remains: If Genevieve Briand was mistaken—and she was—then exactly how many excess deaths are there really in 2020, from all causes, compared to prior years? Using the latest CDC data, we can know this with relative precision for 2020 through the week ended September 16.

For the calendar years 2014-2019, through September 16, the average number of deaths from all causes (adjusted for population growth) was 1,991,648. For 2020 through September 16, the number of deaths from all causes was 2,302,633. This means that over the first 37 weeks of 2020, there were 310,985 more deaths in the United States than should be expected based on the averages from the six preceding years.

The fact that 310,000 people in the United States are dead who would likely still be alive in any ordinary year means, at the very least, we are not dealing with a hoax.

And even though the pandemic shutdown may be killing jobs and robbing thousands of people of their will to live or ability to receive diagnostic screenings, suicides and deaths from deferred medical treatments cannot begin to explain the spike in deaths back in April, when these lockdowns had barely begun, and total deaths were 46 percent above the average for a normal week in April.

The point of this analysis is not to suggest the measures that government officials—federal, state and local—have taken are the correct ones. Some states have done better than others at managing the COVID-19 crisis, and most everyone has had to deal with unknowns and uncertainties in a situation where the stakes could hardly be any higher.

And for those who are conspiracy-minded enough to think the novel coronavirus is not all that serious, based on the fact that most of its victims are older people with serious preexisting health conditions, then they should be conspiracy-minded enough to realize that if this pandemic doesn’t get everyone into line, then the next one will be engineered to be deadlier.

How much of a skeptic do you have to be these days to consider the chance that COVID-19 spontaneously arose in a Chinese “wet market” versus the chance that it was engineered and spread deliberately to be an even bet?

Ultimately, however, in an age when you can’t trust anything coming from the media, and less than ever from the government, maybe this analysis is a useful way to remind us all that even if we’re dealing with official misinformation on almost everything that matters, that doesn’t mean that everything we’re fed is false every single time.

It’s a reasonably safe bet that the numbers presented by the CDC on weekly deaths from all causes in America are accurate, once you take into account the lag in getting all the data compiled. And it is also reasonable to question alternative media as diligently as we question official media. We live in an age of information war, and as in any war, both sides have their inevitable share of charlatans, hacks, and just plain careless players.