My father, a bear of a man who immiserated my life in ways too bizarre to recount here, ended up saving it as well. I was a strong and outgoing boy from the time I was small, but I often felt sad or depressed, in part because the old man’s abuse or recklessness had caused me to sink into such despondency. Yet he also offered a way out.

“Buck up, buddy-o,” he’d tell me whenever he saw me sulking. “Go lift some weights, go talk to people. It isn’t that bad out there. Ask someone to go get ice cream with you.”

This was the summation of the ethos honed during my father’s 1940s boyhood, a cracked-mirror version of a Norman Rockwell illustration by way of Walker Evans’ photos of impoverished, pellagra-afflicted hayseeds. He endured hardship and misery, and although the psychological fallout caught up to him later in life, initially he overcame it by adhering to a philosophy derived from Charles Atlas muscle-building advertisements.

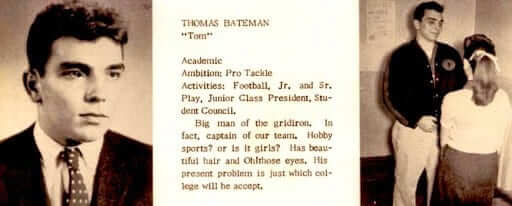

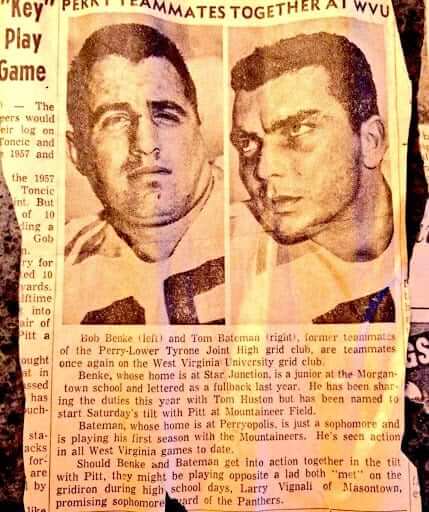

Push-ups, handstands, and wind sprints gave him the strength of body needed to manhandle fellow athletes from Pennsylvania’s “coal patch” region while also weathering blows from his hard-as-nails, ex-submariner father. And after reading that Los Angeles Rams All-Pro guard Duane Putnam transformed himself from middling NFL prospect to superstar through heavy training with barbells and dumbbells, my father—a student of the sport who harbored similar ambitions—began lifting weights.

His efforts took him to Morgantown, West Virginia—a sedate college town in the northern part of that state, but worlds away from Whitsett, Pennsylvania, the tiny little nowhere spot from which he hailed. His family life remained chaotic, but he found solace in butting heads with other athletes, reading cheap pocketbook editions of Beat Generation classics such as Ask the Dust and Naked Lunch, smoking “grass” with dormitory suitemates (all-time basketball great and WVU classmate Jerry West was said to be among them, although this is probably a spurious post hoc embellishment), and going out on dates.

The rest of my father’s life had its ups and downs—mostly downs, owing to a combination of recklessness and malign indifference—but he never seemed to lose confidence in his body, even when he weighed in excess of 400 pounds. He was functionally fit and strong, albeit obese, and he continued to “get his rocks off” crushing apples and ripping up phonebooks to impress his sons and subordinates. And while I didn’t much care for the man, I bore the thousand injuries he dealt me as best I could and have no further need to seal him off behind some wall of repressed memories.

I do have to confront a cruel paradox related to his life and legacy, which is that he taught me to live in my body, at the same time that he was abusing mine with his.

Whether planned or not, he eventually saw this as a way of getting me to my destination unscathed by others. “I hit you pretty hard a bunch of times,” he wrote to me in an email sent a few months before he died. “Pretty good but nothing like my old man. He gave me some beatings I will never forget, real good ones. You wake up in a cold sweat. Take a beating of the ass and say, ‘is that the best you can do?’ They can whale on you but if there’s no fear they’re just beating the meat.”

Here, once again, I’ve taken the shortest way home by means of the longest way round. We live, I’m sad to say, in an era in which so many people—such miserable people!—hate their bodies and hate the way those bodies interact with other bodies. Oh, they certainly talk about their bodies a lot. Perhaps they despise how their bodies feel, yet wish others to think “positively” about them, and so demand some kind of lockstep compliance with their various pretenses.

Or maybe they want to guilt others into saying their bodies are X when they’re actually Y: I must not only find them attractive or interesting, but as a mirror reflecting only the ever-changing ways that they prescribe I admire them, lest I be guilty of “fetishizing” some externally-perceived feature they don’t like or refuse to accept.

On such matters, I long have remained neutral, because I don’t care as much about bodies—my own or those of others—as most of my peers. I don’t post selfies alongside captions about how I’ve overcome my hatred of my body enough to post the selfie you’re looking at, in the hopes that my compliment-fishing will win your approval (but don’t objectify me, please!).

I have always wanted my body to be two things: functionally strong and healthy, and completely my own. My facial features are flat and broad, with a large, squared-off noggin complemented by a wide nose and slightly crooked teeth that never knew the procrustean agony of braces. Am I prepossessing, dashing, fetching? I leave that to others to decide, but anyone like me who has been married for a decade or more probably doesn’t care all that much about the answer.

What I need my body to do, and what, for now, it is able to do, is to display strength and resilience for my daughter. I want to be the immovable rock upon which the foundation for her lifetime will be laid. I can’t waste my waking hours obsessing, narcissistically and in vain (all is vanity!), about the hydro-dipped paint job people are meant to be impressed by if the chassis supporting it is infirm.

We need strong bodies to support ourselves as we struggle to survive during trying times that appear likely to reshape the world of work forever.

“Strong people are harder to kill than weak people and more useful in general” is a catchphrase of strength training coach Mark Rippetoe that now hits closer to home here in the age of COVID-19—a time when both public gyms and workplaces are largely closed, driving anxious citizens deeper into their homes, their minds, and their social media timelines.

Mind you, absent steroid supplementation, each person can get only as strong as their own genetic ceilings allow them to become, accounting for time and access to barbells and atlas stones. Whether you’re bound to a wheelchair or even a hospital bed, however, strength remains superior to weakness. And anyone can get stronger, anywhere and without any fitness equipment at all, as Charles Atlas and his latter-day bodyweight gurus like Pavel Tsatsouline have spent their careers reminding us.

But we also need strong bodies to support each other. Part of dating, which for me meant interacting with interesting people with only the vaguest of romantic intentions, involved learning about these other folks and determining if we could collaborate to build something greater than ourselves. Such a project, the project of constructing a relationship and perhaps even a family, would surely be difficult, but how could it get off the ground if both people hate themselves and manifest that hatred by wanting each to love the other on their own idiosyncratic terms, for weaknesses they refuse to work together to transform into shared strengths?

Dating, in other words, was about becoming comfortable with myself and others. Two decades ago, it wasn’t mediated by online swipe-left apps or such things, but instead was dependent on physical proximity and perhaps sharing a handful of interests or a certain degree of physical attraction. I never had any of the awkward or painful encounters that are now routinely lamented by modern writers, as if courtship itself were nothing more than a vale of tears or a blood-splattered meat grinder, and though my vanilla dating episodes may have something to do with being a lifelong teetotaler, a good portion of it stems from the fact that I never found myself sitting opposite my date, by turns totally disembodied and lost in cyberspace or loathing the skin I’m in.

This, perhaps, was some vestigial form of “jock privilege” of the sort that a New York Times op-ed writer lamented when trying to understand why she felt more at ease around jocks than nerds (“all the news that’s fit to print,” to be sure!). But it was also because the “jock life” of amateur wrestling and powerlifting had rooted me quite firmly in my body, this skin I’m stuck in, and thus freed me to treat my would-be partner as a subject of curiosity rather than an object of desire.

By all accounts, I was a boring date, a real cardboard cutout redolent of 1950s letter jacket-clad meatheads. One woman who ghosted me avant la lettre, way back in the early 2000s, even told me as much years later, when she was shocked to discover my inner life was far more complicated than this placid, inoffensive surface I presented. “You never asked about any of that,” I told her, to which she responded that she didn’t ask because she was working on herself.

I pondered her answer up to the moment I began to write this essay. That, I now realize, was the Rosetta Stone, the key to deciphering the code about what it all had meant. I suppose one could argue that I’ve also “worked on myself,” whether in a gym or in front of a keyboard, but none of this work was lavished on my self. That self never interested me at all. It was the same self that always belonged to me. “Who makes you different from another? What do you have that you did not receive?” the Apostle Paul asked the Christians of Corinth. “And if you received it, why do you boast as if it were not a gift?”

My self, bequeathed to me by generations of ancestors who hewed wood and drew water while

somehow surviving to pass their own lives to descendants, was merely their gift to unwrap here in the present. I owed it to my parents and grandparents to become as double-tough as they were—as inexterminable as the cockroach!—and I owed it to everyone else I encountered to learn about their selves, and the bodies in which those selves resided, as I tried to determine if I was worthy of the greatest prize of all: a life that could intersect, for a few weeks or months or years or forever, with my own.

I state that not as some Pollyanna or Pangloss, but as a Child Protective Services-stamped survivor of the various abuses—sexual, emotional, and so on—upon which so many sad people dwell, unable to forget and unwilling to forgive. No, I know we’re all broken people, in broken bodies, but life is about repair and reconstruction, not commiseration. My father beat me down yet he also gave me the wherewithal to build myself back up. And I went on dates not to tiptoe around vulnerable, flawed people I had been conditioned to perceive as hysterics cursed with eggshell psyches, traumatized by the fast and ceaseless triggers that characterize this era of liquid, ever-shifting modernity, but rather to meet happy warriors who might accompany me along some, if not all, of the stages on life’s way.

Side by side, body by body, we two would bear up against the inevitable death sentence that each life carries with it. We would empower and redeem each other, and hope to leave to posterity whatever was in our power to create or conserve, before passing on like all those other nameless ancestors who survived just long enough to ensure that we received that puncher’s chance, too. There would be no time for hatred of this or that minor physical flaw, no time to waste idle hours beautifying our bodies or taking the perfectly angled photo to win the tightly-moderated comments of perfect strangers, because something far greater was at stake: the future of life itself.