In the small Southwestern Pennsylvania coal-mining town where I grew up, the locals kept to themselves and were notoriously tight-lipped when it came to praising anyone for anything. The elderly residents—mostly descendants of Slovak and Croatian immigrants who came to the town to work the mine—were pessimistic people, distrustful of the Democratic politicians they voted for and resentful of the pretensions of the younger folks who had moved away to bigger cities, such as the 20,000-person county seat 30 minutes east on Interstate 70.

But men like my maternal grandfather did have one particular compliment they doled out as sparingly as the chipped ham or sardines they arranged on slices of white bread: they would note with approval when someone could “handle himself.” This person, usually a taciturn mine worker reminiscent of the cart-horse from Orwell’s Animal Farm or a stout widow who kept her tiny company house in immaculate condition for decades after her spouse’s demise, demonstrated considerable strength in the face of the decay and decline of their dwindling piece of the world.

They matched their personal force, such as it was, against the impersonal force of socioeconomic change. And whether this was right or not, seemingly able-bodied people who complained or even asked for assistance may have received it but were despised for their weakness.

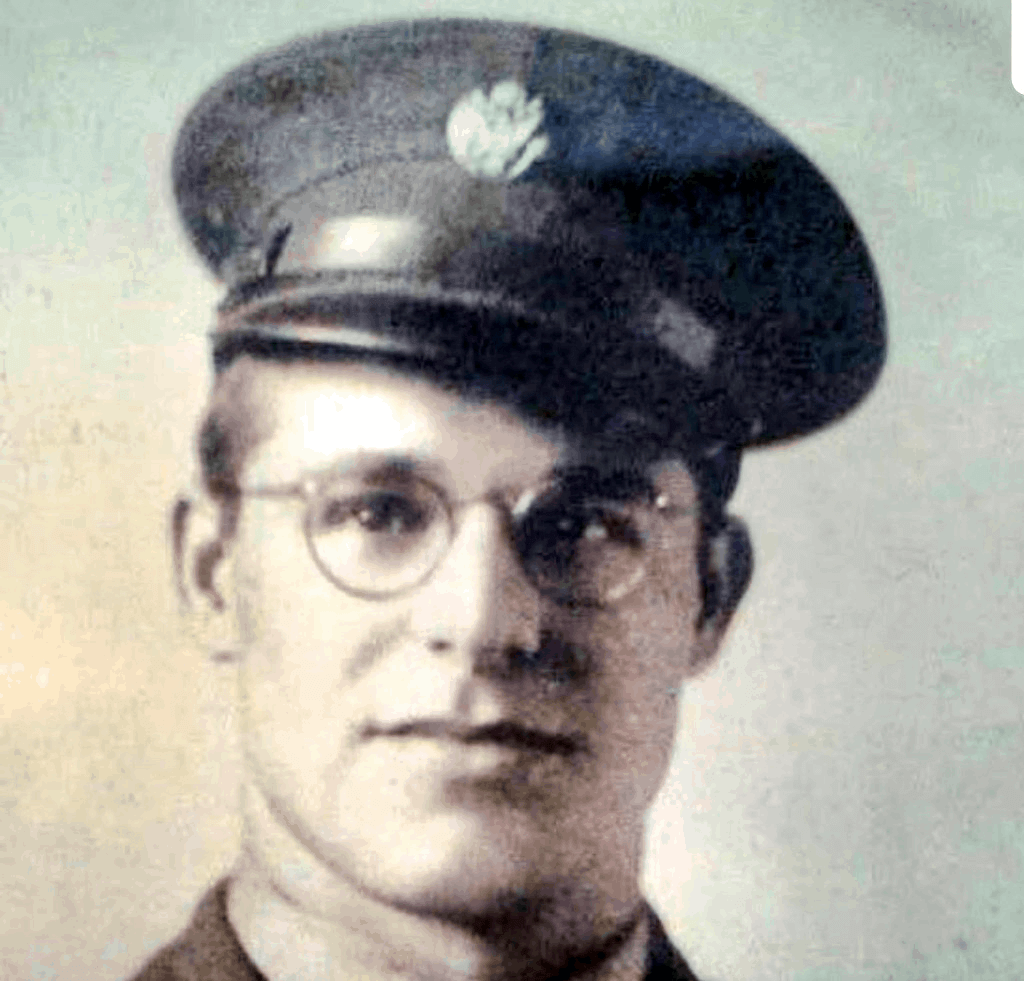

Walter Stechly, the author’s grandfather, in 1942.

I spent many summers with my grandfather. My half-brother, older than me by a decade, helped him lay bricks, insulate walls, wire and then test electrical circuits, and replace outdated lead plumbing pipes with PVC. I, by contrast, was given the simpler task of smashing aluminum cans with a rubber mallet. Since he drank 20 or 30 “lite” beers a day—Stoney’s was his preferred brand—the supply of cans never diminished regardless of my efforts.

After I had smashed several hundred cans, he took them to an aluminum recycling facility in exchange for a small sum of money, which he shared with me in proportion to the quality of my efforts. He rarely approved of the way I smashed the cans because the results were usually asymmetrical. He preferred an even crush as he could do himself merely by placing his massive hands on the top and bottom of the can and exerting pressure. “Look at your brother out there shoveling like he has a steam engine,” he’d tell me, proud of the hulking adolescent laborer who wasn’t even his blood relative. “He’s OK. Your brother can handle himself.”

Handling Oneself in Strength

All through my youth, I approached problems and challenges through this lens. Could I “handle myself” against peers, siblings, and abusive parents? The point, as I understood it, was to bear up under the unbearable—not to invite this pain out of some misguided lust for martyrdom, but to endure it for as long as necessary to escape.

For my grandfather, who had served as a medic during World War II and witnessed considerable carnage during the invasion of Italy, there were no victims in life, only survivors. Surviving, by extension, conferred only a limited right to continued existence: you lived to fight another day, for what that was worth. “Still sucking wind,” in his words.

I went on to endure my own hardships, absurd, and avoidable difficulties precipitated by my parents’ criminal behavior, and I tried to overcome them with ceaseless exertion. Strength, I reasoned, had to be met by strength. As I listened to lectures on early Christianity during college—a period when I worked 40 hours a week to pay my way—I contemplated those rich Romans who, upon discovering the religion in the wake of blood-soaked contributions made by its original martyrs, had sought to acquire their patinas of saintly suffering in the marketplace of public religiosity.

I puzzled over those patricians who gave away or sold their luxurious country villas and accompanying latifundia to journey to Asia Minor and set up residence in a cave or atop a high pillar, punishing themselves in various ways to resist what they perceived as their basest animal urges. Their decisions to openly embrace weakness, as contrasted with those humbler martyrs and hermits who had no choice but to suffer for their faith, gave them a special status during a time of imperial decline: they were “athletes for Christ,” experiencing intense privations to showcase their spiritual mettle even as their civilization declined in power due to plague, warfare, and bureaucratic mismanagement.

I recount all of this backstory because, at least in this case, the shortest way home—meaning to that home described in my first few paragraphs—happens to be the long way round. There, the distinction was made between those members of the community who could “handle themselves,” often in spite of insurmountable odds, and those who begged for assistance even when presumed capable of standing on their own. Help was always given to the latter by relatives, grudgingly of course, with the assumption that those in tight spots eventually wouldn’t be.

In other words, these “victims” of life itself were thought to occupy a temporary position. They might have fallen short, but the belief was that they could regroup, redeem themselves, and restore their lives to whatever status quo ante was in place before their troubles. That didn’t always work out in practice back in the 1980s, and with the town’s population in 2020 half of what it was then while opiate intake is probably many orders of magnitude greater, it likely works out even less often now.

Nevertheless, “handling myself” was the mental construct that carried me through a significant stretch of poverty and mental anguish. I wasn’t absorbing blows for the sake of absorbing blows, like a flagellant in a medieval procession or wrestler Cactus Jack in a blood-soaked hardcore wrestling match, but rather to reach the other side, wherever that was.

I would meet strength with strength, whether competing at a powerlifting event, arguing my case in a moot court tournament, or debating with peers in a graduate seminar. I harbored no delusions of grandeur but intended to hold my own. If I received criticism, I would address those issues and improve my performance. Much of my early adolescence, lost in a fog of ill-considered Child Protective Services actions, amounted to one loss after another, but that simply afforded me a deep foundation from which to rebuild.

The Strength of Woke Weakness

But this intellectual beau monde for which I had rebuilt myself, with books and barbells and 12 years in graduate school, is not one that prizes the ability to “handle oneself.” No, this brave new marketplace of ideas is monopolized by those who exhibit the strength of weakness, a strength of weakness that might be somewhat familiar to those late imperial Romans who were thinking of selling the estate and riding off into the high desert to drop some denarii on the salvation of their immortal souls. I write somewhat for a variety of reasons, most notably that a Roman circa 400 A.D. was still convinced that his soul would transmigrate somewhere after death, whereas today’s aggrieved peddlers in this “wokeconomy” propelled by the tail-winds of outrage are very much concerned with their life in this world.

I had not anticipated the development of a world in which status in some agreed-upon, academy-determined category of victimhood would prove sufficient to foreclose discussion of a particular subject. I failed to realize that mere reference to weakness, in particular to having and showcasing the most unimpeachable and immutable weaknesses, would confer such profound discursive advantages. The classic appeal of the late 18th- and early 19th-century abolitionists—“am I not a man and a brother?”—was how my father, who in spite of his myriad other faults had always embraced his own interracial family, explained human relations to me. Anthony Hopkins’ classic line from David Mamet’s script for the 1997 movie “The Edge” stuck with both of us, too: “What one man can do, another can do.” And Jacques Rancière’s emphasis on “the equality of intelligence” in his book The Ignorant Schoolmaster had carried me through my later years, fueling me with the conviction that anyone can teach anyone else anything, provided both parties are sufficiently motivated and open-minded.

Moreover, much of this boasted-about weakness was feigned. The truly disadvantaged—the invisible or less visible poor, disabled, “BIPOC,” what have you—had no stall or kiosk in which to sell their wares in the marketplace of ideas.

Their actual weakness, in many cases, had been assumed by well-educated spokespeople, who claimed to “do the work” on their behalf. Much of this “work,” insofar as I could understand it at all, consisted of accusing other people of not doing the work, not “organizing” (organizing what?), not “doing the reading” (reading what?), not educating themselves (you weren’t “paying them to educate you,” and believe me, I wouldn’t have). Such peremptory statements were meant to function as the end, not the beginning, of a conversation.

In fact, most conversations with others, even others ostensibly allied under the same political “big tent” who conceivably might support a project such as Medicare for All, were no longer possible at all. Only the divisions, which multiplied alongside the contradictions, mattered.

Social media in general and Twitter in particular are not reflections of life itself, the real life in which most good people live and die, but they do provide a cracked-mirror image of the life of the mind. And the life of the mind, insofar as it exists on Twitter, is enfeebled. You might even say that Twitter serves as the life support of the mind. “What a waste it is to lose one’s mind, or not to have a mind is being very wasteful . . . how true that is,” former Vice President Dan Quayle told the United Negro College Fund three decades ago, though these incoherent remarks would certainly have more salience if applied to the ad hominem tweets exchanged between two journalists attempting to “do the work” of getting each other fired from the same legacy media publication.

I don’t believe these people, enraptured by the power afforded them through frequent resort to the strength of weakness, are engaged in “grifting” any more than I believe that some Roman senator who elected the life of an ascetic was some kind of secret atheist looking to score social brownie points for his sacrifice. When they call each other “grifters”—an overused term I used to think applied solely to the kind of schemes depicted in Jim Thompson pulp novels—that is vulgar projection on their parts; it is weakness talking to weakness, insecurity at its most profound. They are enraptured by the strength of weakness, but this over-reliance on that form of power has shaken their belief in even the “woke” morality they profess so cheap and hold so dear, and thus they end up pretending to believe in the amorality of everyone else. It is a mug’s game, turtles all the way down.

Not Handling Themselves

The larger problem is that the strength of weakness, regardless of its merits as a tool for advancing up the intellectual or bureaucratic ladder, is profoundly destructive. It turns its adherents into parasites, after a fashion: their weakness draws power from and is only relative to the strength of others, which must, in turn, be leveled. Everything high must be laid low.

The strength of weakness can topple any social structures in its path, which is perfect for austerity-obsessed bureaucrats and politicians looking to outsource the running of the country to Amazon, but it cannot build them anew. Rome preserved and enriched the inheritance of primitive charismatic Christianity, but as a polity, it eventually became Greek in the East and fractured into a thousand pieces in the West. The “boy who cried wolf,” as shop-worn a fable as they get, allowed the boy to draw the villagers’ attention to his phony plight up until the moment he couldn’t, the moment when an actual wolf attacked his flock.

Of course, this state of affairs, like any other, cannot last forever. The country faces a wholesale financial collapse, with foreclosures, evictions, and a wave of small business closures looming as summer turns to fall, events likely to forever alter the American economy. Out of so much uncreative destruction, precipitated by incoherent and frankly schizophrenic policy-making related to pandemics and protests, we may have the opportunity to rebuild the razed country from its deepest foundation.

Such work cannot be done by those who “do the work” of purporting to speak for the weak, yet in actuality cannot afford for the weak to become strong lest they lose their hard-earned roles as their mouthpieces (“Pity would be no more, if we did not make somebody poor,” wrote poet William Blake, “and Mercy no more could be, if all were as happy as we”).

No, this is hard labor for hard people—people who can shoulder the load and carry the weight, who would even the playing field by strengthening the weak instead of weakening the strong. It is all we can do, those of us who believe we are all men and brothers and strong in both body and spirit, because we must.