Ever since the heinous killing of an unarmed black man by four rogue police officers on May 25, protests and riots have consumed America’s cities. These mass protests have mobilized millions of so-called progressives, incited to destructive fury by well-organized provocateurs. The groups behind this extremism are well known, as are the leftist and anarchist ideologies that propel them.

But another important movement is growing in the United States.

Either neglected or misrepresented in the media as right-wing extremism, this movement originated in rural America, but increasingly it makes common cause with every beleaguered business owner or overtaxed household in America’s cities.

There is nothing extremist about this movement. It is founded in common sense and a desire for justice and equal treatment. As millions of productive Americans find it harder than ever to survive the onslaught of progressive government policies, the movement grows.

The biggest political wild card in American politics today is which of these groups, productive citizens of rural areas and their urban counterparts, or urban progressives, will claim the ultimate allegiance of undecided voters. To help their odds of winning that battle, it is convenient that climate activists wish to depopulate rural areas and concentrate Americans into dense urban cores. Because the more predominant the urban vote becomes in elections, the less likely the average voter is to understand what’s happening in rural America.

Using regulations pursuant to the National Environmental Policy Act, the Endangered Species Act, and countless other laws and regulations including an exploding body of new regulations designed to prevent “climate change,” government bureaucrats and environmentalist litigators are waging an existential battle against America’s farmers, miners, loggers, and, increasingly, the residents themselves.

Just to live outside established urban centers is becoming endangered. In California and other western states, poor forest management has led to cataclysmic wildfires which are being used as the pretext to deny insurance coverage and drive residents out of any fire-prone rural landscapes. Punitive laws governing logging operations have destroyed entire regional economies as logging companies are driven overseas. Mining operations are now shut down far more often than they are ever started in America, despite, for example, a growing national appetite for rare earth commodities to build electric vehicle batteries.

The nation’s farmers also are taking hits from this avalanche of regulations. But some are fighting back.

On May 29, in Klamath County, Oregon, thousands of farmers and community supporters showed up to protest reduced water allocations, announced earlier this year, which threaten to destroy the region’s agricultural economy. The protesters formed a convoy of more than 2,000 vehicles that passed through downtown Klamath Falls and ended up at a rally site in Midland, Oregon. This convoy, with a majority of the vehicles either farm tractors or semi rigs, was over 30 miles long.

Overshadowed by reporting on the mayhem that has descended on the rest of America, this protest didn’t make the national news. Even local news was focused overwhelmingly on the tense standoff that weekend between residents and business owners of Klamath Falls, and out-of-town activists who were trying to import the mayhem that gripped cities from Portland to Sacramento.

But how much coverage would this ever get? Rural America, along with the urban middle class, quietly is being wiped out, and the media writes off the entire phenomenon as “privileged” people getting their long overdue comeuppance.

Nonetheless, the story of the destruction of the Upper Klamath River economy needs to be told, because it is representative of this wider assault. Environmentalists and bureaucrats, backed by billionaire philanthropists and commercial opportunists, have been waging a one-sided war on small farmers, small business owners, energy and mining interests, and pretty much everyone else who does more than write code, tap a keyboard, or in some manner restrict their productivity to intangibles.

The Klamath River Basin

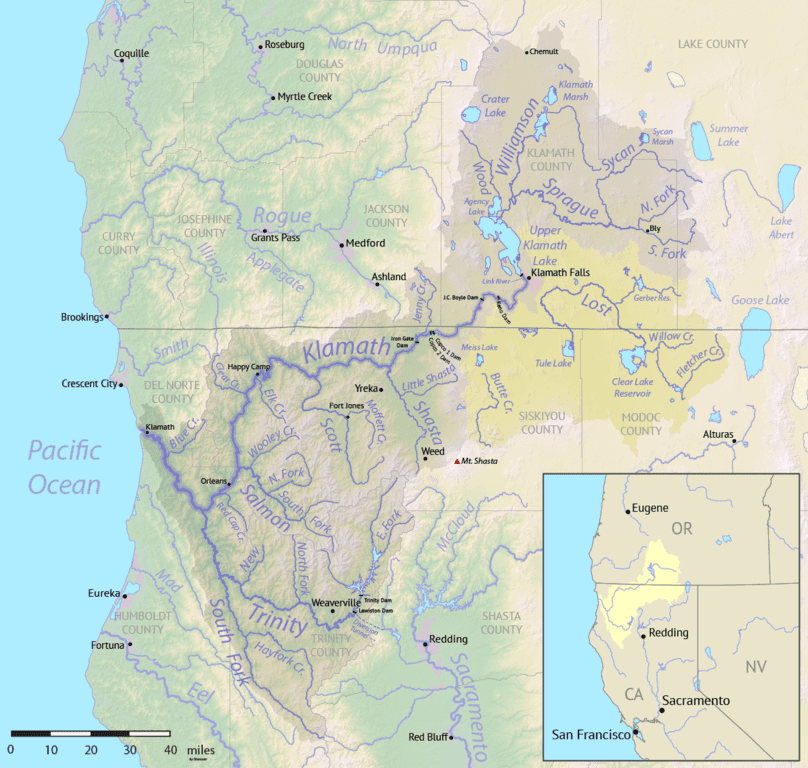

One of the biggest rivers in the Western United States that nobody’s ever heard of is the mighty Klamath, encompassing a massive 16,000 square mile watershed that straddles Southern Oregon and California’s far north. With headwaters in Oregon’s high desert country, the Klamath bends its way west into California through deep canyons, finding the ocean in an estuary roughly 30 miles south of the Oregon border.

The Klamath is distinguished not only by vast extent and its unique topography, but by its importance to salmon populations. Until you reach the Columbia River over 400 miles to the north, the Klamath and its tributaries offer the largest spawning habitat for salmon in North America.

Today, not one, but two serious controversies have erupted over how to best restore salmon populations. The first involves the proposed removal of four hydroelectric dams that are located in the upper Klamath basin.

These dams, three of which are in California and one located a bit further upriver in Oregon, are not used for irrigation, but do supply hydroelectric power and offer recreational amenities to tourists and local residents. At a cost of over $400 million, they are likely to be removed by 2022. While the precedent-setting planned removal of these dams has been the subject of decades of debate, the most serious controversy is further upstream, and concerns water allocations this year for agriculture.

When the Link River Dam was built at the southern end of Upper Klamath Lake in 1921, the intention was to provide water storage for irrigation to what is some of the richest farmland on earth. By the 1990s over 200,000 acres were planted with alfalfa, barley, garlic, horseradish, onions, potatoes, sugar beets and wheat. And then came the water wars.

One of the spokesmen for the farmers is Bob Gasser, who is one of the organizers of the “Shut Down & Fed Up” movement, formed earlier this year to protest the reduced water allocations in the Klamath Basin.

Gasser says that until the water wars began, farmers who were part of the Klamath River Project received irrigation allocations of around 350,000 acre-feet per year. This March, after a dry winter, that allocation was cut to 140,000 acre-feet. Then in April, in meetings with officials at the Federal Bureau of Reclamation, the farmers were told it would be lowered to 80,000 acre-feet, and then in May, to 50,000 acre-feet. Not only is 50,000 acre-feet far less than the farming economy in the region requires to be sustainable, but many farmers had relied on the first allocation, 140,000 acre-feet, and invested in planting crops that will die if the allocation stayed as low as 50,000 acre-feet.

When trying to understand how the fish populations of the Klamath Watershed can be restored, the number of differing answers is equal to the number of experts you ask. But the general consensus among radical environmentalists is that there should not be any agricultural economy in the Klamath Basin. This would be consistent with a growing consensus among environmentalists, which comes closer every year to brazenly declaring that rural and exurban communities should not exist, period. For the sake of the planet and its ecosystems and wildlife, people should migrate into existing urban centers. Only the very wealthy and, of course, the genetically indigenous “first peoples,” shall continue to reside in natural settings.

Practical Solutions to Restoring Fish Populations

Nonetheless, more reasonable environmentalists, according to the farmers, have not paid sufficient attention to evidence that more water does not always equal more fish. There are two fish populations at risk in the Klamath watershed. There are the salmon that spawn in the river, and then upstream there are the suckerfish that inhabit the Upper Klamath Lake—the Lost River sucker and the shortnose sucker.

With respect to the four dams that span mountainous canyons straddling the Oregon-California border, it is likely their removal will have some benefit to salmon populations. The warm water that pools above and below these dams provides a favorable environment for the spores of parasites that attack salmon populations, so removing the dams will reduce their concentrations. This is scant comfort to the people who have lived on the shores of these reservoirs or the tourists who enjoy the boating and fishing they offer, but removal of these dams is all but certain.

Upstream, there has been no serious discussion of demolishing the Link River Dam, built in 1921 to facilitate the Klamath River Project and with a reservoir that is now the lifeblood of the farm economy. There is an irony to the environmentalist solutions because they want to withhold from the farmers the water in the Upper Klamath Lake in order to use that water to flush out the parasitic spores downstream, but this dam is only 99 years old. How did the salmon manage before the dam came along?

This question, does saving water help the salmon, is what Mark Johnson, a staff biologist with the Klamath Water Users Association, attempted to answer.

“Right now the flow event in the spring is intended to disrupt the hosts and reduce spore concentrations for the disease, so they took water off the farm allocation and put it onto the environmental management account which allows the agency to send it downstream at their discretion,” Johnson said. But is increased flow the answer? Does more water equal more and healthier fish?

According to the farmers, the answer is no. They argue that historical data shows that periodic droughts reduce populations of the parasites that attack the fish both in the Klamath River and also in the Upper Klamath Lake. During droughts the lowered flow in the Klamath River dries out the banks where parasites thrive, and similarly, during droughts, the wetlands surrounding the Upper Klamath Lake also dry out temporarily, causing the parasites that concentrate in those wetlands also to die.

As with any complicated controversy over ecosystem management, it’s hard to know who to believe. The farmers point to the fact that over 20 years of maintaining higher water levels in Upper Klamath Lake and maintaining increased, year-round flow in the Klamath River, fish populations have not rebounded. The farmers contend further that lower water levels in Upper Klamath Lake would result in healthier populations of suckerfish. The scientists contend that many other variables come into play and it is misleading to attempt to oversimplify the issues.

Certainly the farmers have tried to cooperate over the years. They agreed to convert 43,000 acres of prime farmland into wetlands in the Upper Klamath Basin. They have consented to reduced water allocations to raise the level of the Upper Klamath Lake, despite the fact that the water level in the Upper Klamath Lake is unnaturally high because of the irrigation dam. They have drought-proofed their operations to use and reuse irrigation water, then return it to the river with a lower phosphate content than the amount that occurs naturally in the lake.

The Farmers Were Heard—This Time

Oregon’s Second Congressional District sprawls across the entirety of Eastern and Central Oregon, and yet avoids encompassing a critical mass of cities and college towns that might turn it blue. Instead, Republican Congressman Greg Walden, who was reelected comfortably by 56 percent in 2018, represents rural Oregonians. When a 30-mile-long convoy of rural dissidents packed the roads from Klamath Falls to Midlands in May, Walden took note.

Hopping a ride on Air Force One to Washington, D.C. a few days later, Walden spent much of the flight discussing the situation in the Klamath Basin with another passenger, Secretary of the Interior David Bernhardt. Then on June 9, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation restored the original water allocation. The press release from the Bureau makes for interesting reading; it makes no mention of the protests or the likely intervention from Washington, D.C. It reads:

On June 2, the Natural Resource Conservation Service forecast for Upper Klamath Lake inflows increased from the May 1 forecast. Based on the updated forecast and ongoing stakeholder input, Reclamation will deliver approximately 140,000 acre-feet to the Klamath Project from Upper Klamath Lake in 2020.

The question, of course, is which was it? An increase in the forecast amount of available water, or “ongoing stakeholder input”? Even with the Bureau restoring the water allocation to their original commitment, this 140,000 acre-feet is only 40 percent of what the farmers get in a normal year. Many farmers will still have to apply for disaster relief assistance. But what could have happened, if the 40 percent allocation were not restored, would have been a catastrophe.

The ‘Science’ vs. the People

The people settled in the Upper Klamath Basin have had to live with this economic uncertainty for over 20 years. Their knowledge of the basin habitat, the mechanics of the ecosystem both historically and in recent years, seems to have been dismissed as folklore by the experts charged with restoring fish populations. But the observations by the locals are evidence-based. Increased river flow and higher lake levels have not resulted in more fish.

No reasonable person would deny that solutions to restoring the salmon population in the Klamath River do not reduce to soundbites and simple answers. But the fact remains that obviously uncertain scientific theories were sufficient to empower regulators to come within an eyelash of killing an entire regional economy. As Bob Gasser stated, looking ahead, “there needs to be a restart on the science, and we have a commitment from the secretary of the interior to look into that.”

The difficulties facing farmers in the Klamath Basin are representative of a nationwide problem. The Department of the Interior is staffed with employees and high-ranking career bureaucrats who, since 1992, operated for 16 years under Democratic administrations, including eight out of the last 11 years. As anyone who has dealt with regulators in blue states will attest, the undeniable professionalism of many of the men and women staffing these agencies is in perpetual conflict with the culture, which invariably is hostile to business.

Bureaucratic inertia alone is enough to make most federal agencies biased against the people in favor of the environment, always citing “science” as the ultimate arbiter. But on a question as complex as how to manage a watershed that occupies 12,000 square miles, “science” is rarely settled.

The fact that “science” has become an overused, politicized shibboleth, extends to every area of policy, certainly including the treatment of rural Americans. These would include all those millions of people living on acreage, who, when wishing to dig, cut, burn, harvest, hunt, build, bulldoze, or grade, are continuously forced to choose between engaging in stealth criminality or enduring an expensive and prolonged regulatory process with crippling intent and capricious outcomes.

At what point might a critical mass of Americans realize that environmentalist overreach is the reason that homes are unaffordable, freeways are congested, energy costs too much, water is rationed, jobs move overseas, and businesses that remain can barely survive?

When will a critical mass of Americans realize that while reasonable environmental precautions are in everyone’s interest, excessive restrictions only serve the agenda of multinational corporations that make more profit when small-but-rising competitors who can’t afford to follow all the rules are wiped out?

When will a critical mass of Americans realize that what happened in Klamath Falls is happening in slow motion everywhere?