Do you speak Bug? Do you know its diction and syntax? Do you recognize its cant, the clicks and stridulations?

If you are reading this, you almost certainly do. You are, more likely than not, well-versed in its rhetoric. Bug is a second language for you. The superstratum of the hyper-educated class to which you belong. It is a language you need to survive here, to effectuate your role in the “knowledge” economy. Bug is the lingua franca of globohomo.

“Globohomo”? Can I say such a word? Not in the boardroom or in the faculty lounge, that is for sure. Not at my TedTalk or the panel I will sit on at the World Economic Forum in Davos. Globohomo is not a Davos word. It is not a Bug word. Its connotations are much too vulgar. It does not, in fact, even matter that you understand precisely what it means. One can intuit its pejorative capacity, its intent to offend. It is a word with verve and weight—a pulse. It is one of many such neologisms arising out of the anarchic ferment of the too-online subterranean world anons like me inhabit.

Here we do not speak Bug.

OK, so what is this Bug language exactly? What follows is a recent, prominent example via negativa. Just about any of Donald Trump’s utterances would qualify as the opposite of Bug, but his letter to Recep Erdogan in October encouraging the Turkish leader to cooperate on the issue of the Kurds is especially instructive. This is what Bug is not.

You might remember the furor over this letter, these final lines in particular:

History will look upon you favorably if you get this done the right and humane way. It will look upon you forever as the devil if good things don’t happen. Don’t be a tough guy. Don’t be a fool!

A conspicuously Trumpian ultimatum. The style is inimitable, Trump’s alone. Brusque, temperamental, masterfully trollish, eschewing the usual niceties and mealy-mouthed platitudes of diplomacy which, to the ears of a swaggering, ersatz sultan would be rejected anyway.

Nassim Nicholas Taleb, another man who does not speak Bug nor think within its constraints, praised the virtue of Trump’s epistolary flair. He compared Trump’s missive to the famous Zaphorian Cossack’s Letter to Sultan Mehmed IV. Below, a sampling:

Zaporozhian Cossacks to the Turkish Sultan!

O sultan, Turkish devil . . . Thou shalt not, thou son of a whore, make subjects of Christian sons; we have no fear of your army, by land and by sea we will battle with thee, fuck thy mother.

Thou Babylonian scullion, Macedonian wheelwright, brewer of Jerusalem, goat-fucker of Alexandria . . .

So the Zaporozhians declare, you lowlife . . . Now we’ll conclude, for we don’t know the date and don’t own a calendar; the moon’s in the sky, the year with the Lord, the day’s the same over here as it is over there; for this kiss our arse!

“Goat-fucker of Alexandria . . . ” Imagine!

Trump’s own letter is so mild in comparison; and yet, what did our Bug-speaking class have to say about it?

It is hard when adjudicating anything Trump-related to disaggregate their reflexive contempt from a more substantive critique, but here we see their old point-and-sputter routine to dismiss what they cannot (or refuse to) comprehend. Bizarre, they say. “Is this, like, even real?” they wonder. Do a Twitter search for “Erdogan” on October 16th, 2019, the day the letter became news and you will see for yourself. The Bug class screeching in unison, performing ironic dramatic readings. The cringe is unbearable.

Forget the utility of the letter; they do not even bother to take aim at the question of whether or not Trump succeeded in deterring Erdogan’s aggression. Erdogan threw the letter in the trash, don’t you know? As if that is the end of it, or tells us anything at all about the foreign policy matter at hand. No. What they most resist are the aesthetics of the letter. They resist its style.

“Trump writes like a man wielding overwhelming power, held back only by generous restraint,” says a Bug-speaking columnist at the Guardian. As if that is a bad thing! What matters is not that Trump did or did not persuade Erdogan. Trump’s great sin, as one presidential historian and CNN contributor put it, was that he failed to “look professional.”

Much is revealed by this concern over professionalism. Much more than Trump’s accuser intends, and it is not about Trump but about the function of the Bug language as perceived by the people who wield it and enforce its use. The appearance of professionalism is the overriding ethic. This is what the Bug language affords, a thin veneer of legitimacy. It is cosmetic, purely, a layering over of a much more sinister, much more repugnant creature underneath.

Cultural Revolution

Let us go back to beginnings. Christopher Caldwell’s much-discussed Age of Entitlement makes the provocative claim that the origins of the modern American nation (and the death of the old one) can be traced to the Constitutional cataclysm of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. He observes in this episode the hardening of a certain progressive legal and political impulse seeded in the suite of new laws, including Hart-Celler, that would come to dominate American life, and by proxy the Western world at large, in the decades to come.

Caldwell notes this wasn’t merely a legalistic revolution, even if the courts supplied the arms, but also activated through social and cultural practice a much broader reorientation of the commonweal toward a coalition of minority interest groups and administrative state commissars, at the expense of a white working-class who under this new dispensation were obliged to take their ration of gruel with a smile.

One of the mechanisms Caldwell identifies for this social and political conquest is the old conservative bogeyman of political correctness. The dopey, ham-handed manner in which the term is so often criticized by the Right notwithstanding, an examination of P.C. provides an illustrative example of how language—the Bug language, of which political correctness is a major idiom—is used to enforce ideology on otherwise unwilling subjects.

Take the case of the nauseating term “Latinx.” Go ahead. Say it out loud to yourself. Latinx. Do you feel properly debased? You should. You are meant to. Your indignity is the point.

Bug language cannot be allowed to persist. And we must stomp it out with the heel of our boot.

Nevermind for a moment that the vast majority of people the term is ostensibly meant to assuage do not like it and would never use it themselves. Like so much else that might fall under the umbrella of P.C., the goal is not to empower the weak but to weaken the strong. And a term like “Latinx” does this firstly by extorting consent through moral blackmail—you are a bad and discourteous person for not using it—and secondly by smuggling in with its adoption a whole matrix of ideological commitments from which the term is constructed, including commitments related not just to Latino ethnicity, but to gender, sexuality, immigration, and even American foreign policy. The Bugmen who invent this stuff say so themselves.

Reader, you might resist using the term. I suspect you do. Just as you might resist declaring your pronouns, or saying the equally nauseating term “person of color,” or examining your “privilege,” white or otherwise, or renouncing your “toxic masculinity.” At least for now. But where these terms fail to take root, others of their type will spread and claim the soil, and inexorably the ground from which we derive our understanding of the world and our place in it, becomes choked with these verbal weeds and the poisonous fruits they bear.

But this is not all that is going on. Lamenting the scourge of P.C. is by now prosaic culture-war sport and not really even the most interesting aspect of Bug speak. The civil rights revolution at the center of Caldwell’s thesis dovetails with another era-defining revolution of a subtler kind that perhaps better elucidates this subject.

Financialization and the Rise of the Managerial Class

For our purposes, it will suffice to give a potted history of the class divisions and alliances that emerge alongside Caldwell’s civil rights revolution. The trends are related and feed on one another but should be understood as separate phenomena. The story of the managerial class, the progenitors of Globohomo and the language he instantiates, opens with the financialization of the American economy in the 1970s.

In the cauldron of burgeoning American global economic hegemony, the witch doctor(ate)s in the academy and on Wall Street cooked up a new, more potent scheme to extract resources from firms and their labor. The finer details are better explained elsewhere.

What’s important to understand is the creation of new wealth under this scheme, if not the result of a “casino economy” exactly, depended less and less on the production, sale, and consumption of goods and more and more, as David Graeber puts it, “[on] various forms of rent taking, that is, direct extraction, through semifeudal relations of extraction where financial interests work closely with state power (‘policy,’ as it’s euphemistically termed) to create conditions of mass indebtedness.”

This is the neoliberal economy at the End of History: a shell game that coerces Peter, if not to steal, then to borrow beyond his earning capacity to pay Paul, where owner and worker, no longer adjoined by lifetime employment, a pension, a shared community where their respective children attend the same schools and might even (gasp!) marry, are instead cut off from one another, the owner having made common cause with financial interests and the public bureaucracies that dole out his gibs, while the worker is left to fend for himself against mass imported labor, in decaying, alienating cities and towns, his union busted, his pension depleted, and his sons subjected to the haradins and gremlins in the media and in the lecture halls who blame him for society’s ills.

Melodramatic? Maybe. But only a little.

Into this milieu, a new antagonist emerges. The managerial class.

Broadly speaking, the upper quintile or so of highly educated, relatively well-paid paper pushers and desk jockeys whose primary duty is to keep the corporate-bureacratic machinery well-greased. Much, perhaps most, of it is not real work. Not in the traditional sense of value-added inputs. Instead, it is inflationary makeshift drudgery to justify the continuation of its own existence. Mandarins puttering about with a pair of meddling eyes over every shoulder. Needlessly convoluted procedures, rules, redundancies, instructions, prohibitions, and laws are the grist for the new corporate mill, serving, again, per Graeber, the “flunkies, goons, box tickers, and task masters” who populate the modern office.

Here, then, we get another condition out of which the Bug language is born. It is a do-nothing language for do-nothing people. Its flimsy abstractions and moralizing sentiments serve both to explain away the dispossession of the working class over whom the managers preside, and to substantiate their status that is increasingly decoupled from any actual merit. Hence, officespeak. HR drivel.

MBA Harvard. Forward Optimization Analyst. Delivering strategies to achieve excellence across domains. Advancing underrepresented managers within an Inclusion and Diversity capital and technological ecosystem.

You have seen this on Linkedin. I have. What does this Bugman do? What purpose could he possibly serve? It is a language to describe the clothes of a naked emperor. A profoundly deceptive, ever-permutating glossary of buzzwords and junk phrases to sustain the illusion that the professional degrees mean something, the six-figure salary is deserved, and their complicity in undercutting your grubby-handed countrymen nil, if such a thought might ever surface at all.

This verbal (self) deception, a discharge of pustulating insecurity, and the dim awareness of the hours, days, years wasted on endless busywork, relates to a third and final condition of Bug speak, “elite overproduction.” As more and more Harvard MBAs are minted, as well as college degrees across the board, especially graduate degrees—college loans being a necessary pillar of the financialized economy’s mass debt superstructure—the relative status value of the degree is proportionally deflated.

But the petty status games go on, and where the intrinsic value of the Bugman’s credentials are debased, a Bug vernacular is constructed to prop it back up.

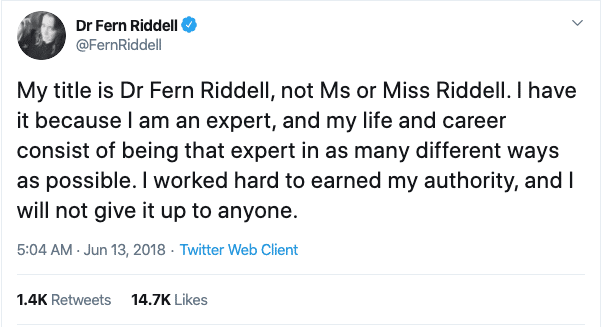

In its Platonic form:

One sees this more and more. The besieged, officious Bugman, demanding with increasing desperation her due respect and acknowledgment of her “expertise.” If this is not status anxiety, I don’t know what is.

These self-proclaimed “experts” and their water carriers are perhaps the worst offenders. Every pronouncement begins with a declaration of their assumed authority. It goes something like this: “Doctor here. I spent years training how to put on an N95 mask. It is impossible unless you have a degree like me. So don’t even try, plebe.”

They say this. In so many words.

The purpose, again, is always to weaken you, to subjugate you, to patronize and condescend. Without their help, or their degrees, you are not even fit to wipe your own ass. Do not better yourself, do not defend yourself. Submit.

That is the telos of the Bug language, to lead you into submission. Bound and gagged.

What Comes Next?

In writing this essay, I do not mean to suggest that Trump’s too-often caricature-like bluster, for example, is what serious people ought to adopt to displace Bug language. Nor should we all begin speaking in memes and other obscure online jokes. Though we must maintain a sense of humor and a sense of play. Our sense of humor is one of our great advantages over the Bugmen. And our memes, and Trump’s, certainly have a place, and at least provide a striking contrast to Bug language that can, and has, shaken many a soul out of their Bug-induced slumber.

But this is not merely a call for a coarsening of the discourse exactly, though some coarsening is in order. Rather, I want to insist that language is the vehicle through which its speakers’ material and spiritual needs are both defined and met, and to the extent Bug language has been adopted by our public and private elites, in the United States and around the world, we have been accordingly reduced to stuttering, impotent, homunculi of the mind and soul, estranged from our own humanity and that of our fellow man.

One must refuse their terms. One must not enter into their status games. One must not be held hostage by threat of moral extortion and declare of himself or of others what he does not believe to be true. One must not be debased. One must not get bogged down in legalistic hair-splitting or “pedantic empiricism.”

“Well, akshually . . . ” Fuck off, akshually.

Richard Weaver (read him!), the mid-century conservative rhetorician, had much good to say on the topic of how we might communicate our ideas. Perhaps foreseeing the rise of the Bug language, Weaver warned of basing our claims too much on authority or the crude accounting of consequentialism. This was the way of the technocrat.

Instead, Weaver asserted, we must concern ourselves with principles, with essences. “Rhetoric in its truest sense seeks to perfect men by showing them better versions of themselves, links in that chain extending up toward the idea.”

Heady stuff, no doubt. But a language that allows us to think bigly, allows us to do bigly.

On the day I began writing this, Marc Andreesen wrote an impassioned plea that our nation start building again. It is a powerful statement, spoken from a place of deep longing, and I believe he means every word. I will leave it to Andreesen to sort out the financing, the tech, the coordination required to fulfill such a promise.

But I will suggest that none of this can be done—not the flying cars, or the space travel; there will be no fourtth Industrial Revolution—until and unless there is a common language with the capacity to inspire it. His declaration is a start. But Bug language will not allow it. It cannot support its vision. It can only pervert, and inevitably thwart all that dare to be heroic. Bug language cannot be allowed to persist. And we must stomp it out with the heel of our boot.