The markets received word of the April 14 OPEC deal with little enthusiasm. Goldman Sachs described the agreement as “historical, but insufficient.” Oil prices largely remained unchanged, and importantly, oil futures failed to rally. As a result, as oil prices prevailing in the futures curve, the market anticipates the liquidation of the U.S. shale sector and many of its suppliers, notably drillers and fracking companies.

The April 14 OPEC Deal

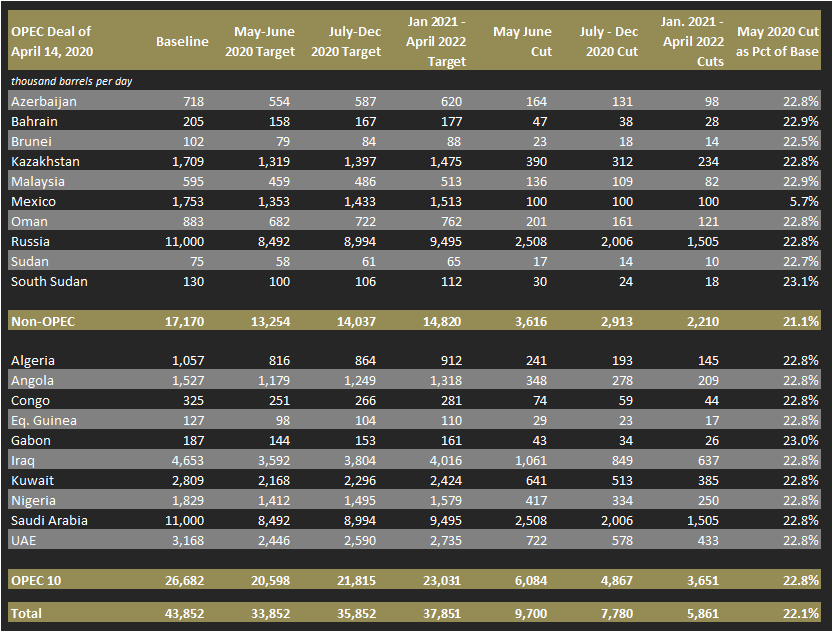

The OPEC deal calls for an oil production cut of 9.7 thousand barrels per day (MBPD) in May and June, tapering to cuts of 5.9 MBPD through April 2022. While this represents a commendable effort, it falls short in magnitude, speed of rollout, duration, and sponsorship. Each of these issues merits consideration.

Magnitude and Speed of Rollout

While a nominal cut of nearly 10 MDPD is no small achievement, we estimate the surplus of supply over demand in April will reach 25-30 MBPD. We anticipate a further excess supply of 22 MBPD in May, 13 MBPD after adjusting for the OPEC deal.

Thus, the OPEC cuts will fall well short of balancing the market.

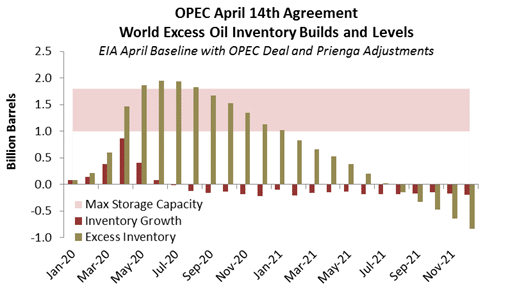

Even post deal, crude inventories will swell by 400 million barrels in May. This by itself would not be crippling, but the delay in rolling out the deal will have allowed 1.5 billion barrels of excess inventory to accumulate even before the agreement takes effect.

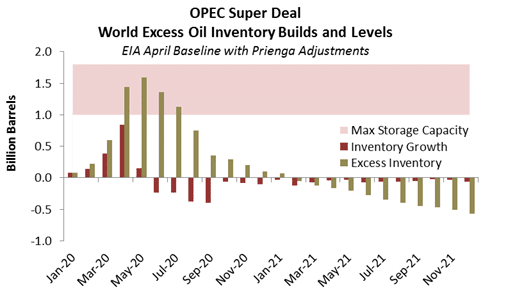

Thus, by the end of May, our projections show excess inventories around 1.9 billion barrels, very possibly exceeding global storage capacity, estimated in the range of 0.9-1.8 billion barrels (in pink on the graph below). As of the writing of this analysis, West Texas Intermediate (also known as Texas light sweet crude) had fallen to $17 a barrel, suggesting crude storage capacity is already effectively committed.

Duration

Burning off excess inventory will take time—about 14 months under the OPEC deal. This in turn implies that oil prices will remain depressed for an extended period—a year or more.

At present, the West Texas Intermediate futures curve implies oil prices below $35 per barrel through 2021. The U.S. shale sector is not viable at these prices; therefore the OPEC deal is fundamentally unacceptable from the U.S. perspective.

Nor does it help deal participants, as both their production levels and oil prices will be depressed. The OPEC deal members face a future only marginally less dire than that of the U.S. shale sector.

The situation may be even worse. The OPEC deal contains the unusual provision of extending production cut commitments for two years during an acute pandemic anticipated to last for only a few months. If participants were to honor the deal beyond mid-2021, the world likely would be facing an acute oil shortage by early 2022, and the futures curve should reflect this anticipated shortfall. It does not, implying that the market does not believe the OPEC deal will hold together when market conditions improve, a view we share.

Implausibly, the deal would imply that participants would materially withhold production even as U.S. shales recovered and began to take market share. Consequently, the conservative view of the OPEC deal suggests that compliance will begin to falter when market conditions improve, and this lack of compliance may further depress market prices, thereby delaying the recovery of the U.S. shale sector.

Sponsorship

The OPEC deal was reached along traditional lines, led by Saudi Arabia and Russia, and extended to a larger consortium including most of OPEC and a number of states of the former Soviet Union. This group, however, represents less than half of global petroleum liquids production of 102 MBPD. A consortium of this size reasonably could not be expected to cover needed cuts of 20-30 MBPD.

A larger group including non-OPEC producers is absolutely necessary, for which U.S. leadership is indispensable.

The United States is the world’s largest producer and consumer of oil. Deep global production cuts are inconceivable without its active participation. To date, the Trump Administration has taken the position that market forces should resolve the problem. While market forces have many virtues, they will produce disastrous results during financial crises and pandemics.

As a practical matter, reliance on market forces will result in the liquidation of the U.S. shale sector and much of its supporting service industry. It is the wrong solution without qualification. America needs a new approach.

An OPEC Super Deal

In a pandemic, we are rapidly learning that responses need to be quick, sharp, and short. A month ago, we could have acted quickly to prevent a surge of inventories. That opportunity has passed. We can still act, however, to sharply reduce inventory builds to prevent long term damage. We call this approach the “OPEC Super Deal.”

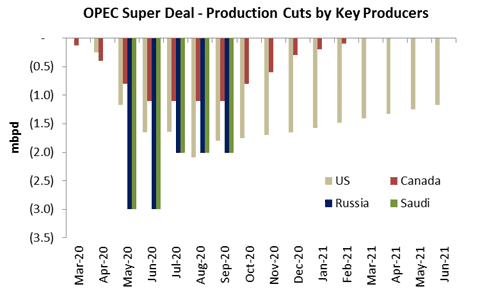

In essence, the super deal seeks to deepen proposed OPEC cuts and broaden participation in the agreement.

The OPEC cuts today represent a reduction of approximately 23 percent from first-quarter production levels. We would seek to increase this cut to 30 percent.

In addition, key non-OPEC producers would be brought into the deal, including the United States, Canada, Brazil, and Norway.

Canada: Canadian producers have stated that they may shut in 1.1 MBPD of production due to low oil prices. This may prove to be the case, but an expectation is not a promise. From the analyst’s and trader’s perspective, a sharp reduction in Canadian output cannot be banked until it is visible. Therefore, a stated intention will have greater—and possibly much greater—impact on oil prices than would speculation about future shut-ins. The opportunity cost to Canada ultimately may prove to be close to zero—the capacity may be shut in either way—but from the oil trading point of view the difference is potentially huge, certainly in timing. By promising specific cuts, Canada could help support oil prices.

Norway: Like the Canadians, the Norwegians have already floated the prospect of production cuts. The Norwegians are practical and principled. If a plan makes sense to them, they will do their share.

Brazil: Brazil has already shut in about 200,000 barrels per day of production. In addition, Petrobras, Brazil’s semi-public multinational oil production company, intends to deploy a number of large production platforms in 2020. A delay in bringing these on line counts materially as a reduction of production during that period.

This brings up an important point. In the pandemic, it is not the virus but rather the exaggerated immune response which kills many of the victims. Similarly, the massive inventory build, not the production surplus, will kill the U.S. shale sector. A deep but limited stretch of low oil prices can be bridged by producers. By contrast, a long period of low oil prices and chronic uncertainty will surely wipe out the shale sector.

The problem is not necessarily attempting to prevent a production surplus, but of preventing massive inventory builds on the one hand, and clearing them rapidly on the other. The production cuts need not be simultaneous, however. They need only be equivalent over some stretch of time, say, six months. A delay in new production can function materially as a production cut for purposes of an agreement. Brazil could contribute not only with production cuts, but also by agreeing to delay new projects.

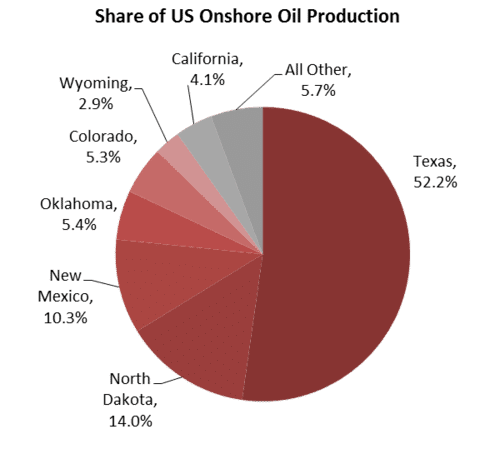

The United States: Limiting production in the United States is a complicated matter. The United States draws oil from three distinct sources: Alaska, the offshore Gulf of Mexico, and onshore in the Lower 48 states. Virtually all of Alaska’s production transits the Trans Alaska Pipeline and is monitored in real time. While the Gulf of Mexico has thousands of production platforms, only deepwater platforms really matter, and their output also passes through pipelines and is monitored in real time.

Federal and state authorities have the capacity to influence the operation of these pipelines. This authority should be exercised, on whatever basis necessary, to secure a reduction of Alaskan pipeline flow and Gulf of Mexico output from large platforms. In our proposal, the reduction would amount to 30 percent for two months, and 15 percent for three additional months, with no restrictions thereafter. In barrel terms, this would represent a reduction of 0.6 MBPS in May and June from Alaska and the U.S. Gulf of Mexico together, falling to 0.3 MBPD from July through September.

Onshore production is another matter. Much of this today comes from shale. High decline rates compel shale operators constantly to drill and complete new wells to maintain production. This is unlike deepwater production, for example. Offshore, the capital investment is largely up front, with production lasting for many years thereafter with comparatively slow decline rates. For example, during hurricanes, production from offshore platforms is shut in, to be turned back on when the storm passes. No new wells have to be drilled or completed. Not so for shale wells. Without constant investment, shale production will fall precipitously.

Shutting in onshore production is problematic because thousands of producers are involved. Most of these are mom-and-pop operations producing perhaps 10 barrels per day. At the other end of the spectrum are the large shale oil operators like Pioneer and EOG, whose production runs to the hundreds of thousands of barrels per day. These differences create divergent realities and challenges in achieving consensus over appropriate policy actions. We believe a better approach would be a moratorium on new well completions lasting between 60 and 90 days from May through June or July.

This may not be as hard as it seems.

More than 90 percent of U.S. lower 48 onshore oil production originates in just six states: Texas, North Dakota, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Colorado, and Wyoming. A new well completion moratorium in just those states would be sufficient to materially reduce U.S. onshore production.

Each of these states has a long history with the oil business. The respective state budgets depend upon the oil sector, and the governors and legislators are familiar with the business and its role in the state economy. None of these states wants to see their shale sector liquidated, if for no other reason than because the state budget will be hard hit as a result. The governors and legislators of these states should be willing to participate in a moratorium which promises to protect the shale sector and offers the best chance of an early return to activity. The politics should be manageable with a little creativity and determination.

Without new wells, lower 48 shale production will fall by about 0.5 MBPD per month. Thus, a two-month moratorium would see production fall by 1 MBPD; a 90-day moratorium, by 1.5 MBPD. Moreover, restarting the sector would take time, adding another 0.5 mbpd or so to the total reduction.

We estimate the equivalent impact of U.S. cuts calculated on the same basis as, say, Saudi production cuts, at 2.8 MBPD, including offshore and Alaska. A new well moratorium in key lower 48 states and curtailments from Alaska and the Gulf of Mexico would yield comparable cuts to those made by Russia and Saudi Arabia, albeit with a different timing and structure.

The Scope and Benefits of the Super Deal

All together, we estimate total Super Deal cuts at 16 MBPD in May and June, and 12 MBPD for the following three months. These steep curtailments would have the effect of clearing excess inventories not in 14 months per the current OPEC deal, but in just six months. That means West Texas Intermediate could be back in the $50 range during the third quarter and shale operations could restart at that time.

The cuts have another benefit. Analysts estimate the world spare oil storage capacity at 0.9-1.8 billion barrels (the pink zone shown in the graph below). Under the current OPEC deal, excess inventories would swamp storage capacity, pushing the front end of the futures curve down. With the cuts in the “super deal,” the futures curve would arc into a much steeper contango. This in turn would provide greater financial incentive to bring alternative storage on line, thereby protecting cash prices and reducing the pressure for involuntary shut-ins.

The Russians and Saudis also have an incentive to participate in the super deal. Enhanced production cuts mean that excess inventories will be cleared before U.S. shales can fully respond. As a result, the world would be looking at a shortage of oil from mid-2021, and this would allow the Russians and Saudis to seize some of the market share which they claim to want so badly. Alternatively they could enjoy higher per barrel pricing. In our scenario, WTI could easily find itself in the $70 range during 2021—an opportunity to recoup some of the losses from the pandemic.

Thirty days of indecision have cost the U.S. shale sector the opportunity to prevent an uncontrolled build of crude oil inventories. Still, the situation is not yet a lost cause. An OPEC Super Deal would limit the damage and foster the quickest recovery of the oil business, including the U.S. shale sector. And it offers the Russians and Saudis the opportunity to compensate for market share lost to U.S. shales in the last several years.

Negotiating a deal is a challenge, but all of the participants have reason to sign on. With determination, fair-mindedness, and good technical deal-structuring, an OPEC super deal is an achievable goal.