I would like to share a short reflection with you on the subject of globalism, from a reading of Friedrich Nietzsche. In The Will to Power, a book that some say does not exist, since it would have been composed from fragments chosen by Nietzsche’s sister—that is an interesting controversy, by the way. But the book exists, since it has influenced several movements, as we know.

At the beginning of that work, Nietzsche states, “What I relate is the history of the next two centuries. I describe what is coming, what can no longer come differently: the advent of nihilism.” He wrote that between the end of 1887 and the beginning of 1888. Therefore, we are squarely inside the second-half of these 200 years in the history of the advent of nihilism, according to Nietzsche. The very concept of nihilism in Nietzsche is extremely complex including his very relation with nihilism, because in the preface of The Will to Power he says something like “I am Europe’s first nihilist, but, simultaneously, I have given up being a nihilist and left it behind.” So Nietzsche’s thinking is, in a manner, a description of this nihilist phenomenon and an overcoming of nihilism, maybe we can see it this way.

Nietzsche is also of course famous for the sentence, “God is dead”—which is not his, by the way; there are many voices inside Nietzsche and that particular line is uttered by a character in a fragment of The Gay Science. That is also another problem in Nietzsche—a problem and solution, perhaps—because you never know exactly who is talking.

But the idea that God is dead became the central principle of all subsequent thinking and, in a manner, of all the later history. Without that radical rupture, from my point of view, one cannot explain either Marxism-Leninism or Nazi-Fascism. Both movements stem from the rejection of God, the rejection of the so-called bourgeois morality, the God-centered moral order, which Nietzsche had destroyed, in a certain way, or whose necessary destruction, for a necessary renovation, he had foretold.

Evidently, one also needs Marx to understand both movements, Leninism as well as Nazi-Fascism. In The German Ideology, Marx and Engels do basically what Nietzsche did, minus his subtlety and multidimensional character, but with the same destruction of the ideas of the current morality. I believe a parallel reading of The German Ideology and Nietzsche’s On the Genealogy of Morality, for instance, would be an extremely interesting research exercise.

What is certain is that Communism and Nazi-Fascism both depend on God’s death. They depend on the end of what I would call anthropotheism, which is the concept of man as a vertical being, who interacts with God and is God’s son. Both institute radical anthropocentrism, perhaps considering that they are thus freeing man, in some way. Both aim at some sort of Übermensch, the socialist man, in the Soviet conception, or the very word used by the Nazis. There is a strong relationship here. And, however, through this false liberation, they actually enslaving the human being.

It is also important to recall Dostoyevsky’s work Crime and Punishment, in which the main character, Raskolnikov, acts on the idea that, if God does not exist, everything is permitted. And it went wrong for him, as we know. Raskolnikov may be the one individual who represents all that later history of the world, or at least of the West. Starting from the principle that God is dead, he faces an entire crisis beginning at that moment in his life, and eventually returns to faith.

Also interesting is a sentence by psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, which I found in the works of an important Marxist philosopher, Slavoj Žižek; at a certain point, he said that “if God does not exist, nothing is permitted.” Though maybe with a different dimension, because I am unsure the exact context of the sentence by Lacan, but, in a manner, I identify with it. I actually think it represents the recognition of that false freedom brought on by the lack of a divine order, a moral order. This idea is seen shortly afterward with the moralism within current globalism.

The Crucified Man

Back to our Nietzsche. The point is: God is dead. To a Christian, that is old news. Christianity is essentially living with that fact, God’s mortality and, evidently, resurrection. Nietzsche himself may be a heretic prophet, but nonetheless a prophet of that rebirth.

It is interesting to read the letters he wrote in the beginning of the period known as his insanity. Nietzsche had his breakdown on January 3, 1889, and on that same day he wrote some letters, mostly notes, to friends and acquaintances. Some he signed as Der Gekreuzigte—”the crucified one.” In one of them, he says Die Welt ist verklärt, denn Gott ist auf der Erde—”the world is transfigured, for God is on the earth.” In another letter, to Cosima Wagner, he asks her to announce Die frohe Botschaft—which is not “the joyful embassy,” since that could have a different meaning to some of us here in the diplomatic field—but rather “the Good News,” the Gospel.

Nietzsche signed other letters as Dionysus, the main god in the mystery cults of Ancient Greece, a god of death and rebirth, frequently associated with Christ in the syncretic cults of the first, second, and third centuries. Curiously, when considering Nietzsche’s famous opposition between the Apollonian and Dionysian, we tend to see in the Dionysian only the side of celebration of life, of freedom, not the celebration of rebirth, therefore, the pre-Christ, pre-Christian character of the cult to Dionysus, which in my opinion would be more appropriate and complete. In a certain way, Nietzsche presents himself as the very crucified; he gives himself up to his own sacrifice, nailed to the cross of his own atheism, which is perhaps a false atheism.

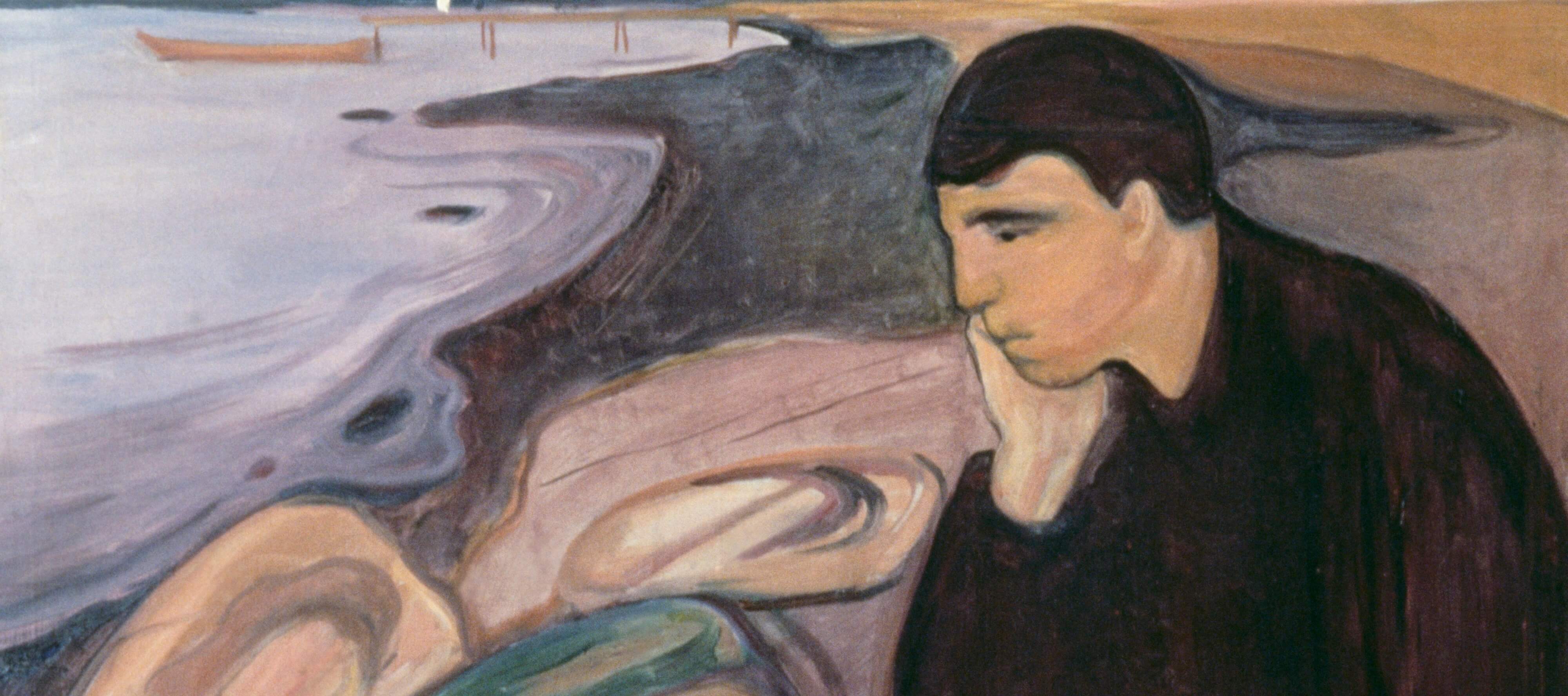

Throughout his adult life, Nietzsche gives himself to this abyss of intellectual anguish, and I believe he presents himself in his books as more anti-Christian, as a “para-Christian” figure, if you will—Ecce Homo, “behold the man,” which is how Pontius Pilate presents Christ before the crucifixion.

Nietzsche foretells many things about the 20th and 21st centuries, in many places. I’m not sure it would be worthwhile to read the 14 volumes of Nietzsche’s complete works in search of these prophetic statements. But I was fortunate to find one of them here, in Nietzsche’s last texts, written in December 1888 and early January 1889, in the weeks and days before his mental breakdown and entry into the “madness period.” Nietzsche writes, “I bring war. Not war between people and people. Not between class and class. I bring war between Aufgang und Niedergang—ascent and descent—between the will to live and revenge upon life.”

First, I think Nietzsche starts out by denying what he in a way also foretells, which is both the concept of national struggle, causing this fight between people and people, which is somewhat the origin of the Nazi-Fascist worldview, and also denying class conflict, evidently the origin of the communist worldview. So maybe we can read the following story as this struggle between what he calls ascent and descent—Aufgang und Niedergang.

It is also interesting to ask who is this I that speaks. As I have said, in Nietzsche we must always ask who the subject is, when he says Ich bringe den Krieg—”I bring war.” This Ich is not necessarily Nietzsche as a person; it is perhaps history, the spirit, and here we touch a bit on Hegel. Anyway, the passage may be read not as a personal statement but precisely as a near prosopopoeia, so to speak, of later history. This war between ascent and descent is perhaps the history of the 20th century or the way of looking at the history of the 20th and 21st centuries, in which we participate now. In that same text, as in many others, Nietzsche preaches a break from all values considered sacred, which is basically what both Lenin and the Nazi-Fascists did. It is the total Niedergang—the descent of man from pure physiology, which is the term he himself uses in the text.

He curiously portrays, let us say, the development of this struggle between Aufgang and Niedergang as the creation of a party. That is interesting because it comes before the idea of a single party, a feature of both the Communist and Nazi-Fascist movements. He says it is necessary; it’s not exactly necessary, he describes the steps of the development of this movement. And he says “a party of life will be created, or must be created, strong enough for the great politics.” And the great politics makes physiology the ruler of all other matters. So it is the idea of man as pure physiology, and a totalitarian political party to impose that physiologism. That is what Nietzsche foretells, or wishes, or preaches—we never know, but that is what he in a way announces, and that is what, for instance, both Lenin’s Communist Party and the National Socialist German Workers’ Party later tried to implement.

From God to Gramsci

It is curious because here in Brazil, to us, the term physiology has acquired, in politics, another very particular meaning, of which we are all aware. Therefore, when Nietzsche says “Ah! Let us make physiology the ruler of everything,” the Brazilian political system replies “I’m on it.”

Well, what takes place along the 20th century is humanity’s terrible dive into this night of physilogism, into this night without God. The question is knowing whether we will ever be able to emerge from this descent. Precisely from those two ideologies, these two movements stemming not from Nietzsche, but from this idea, introduced by Nietzsche, of the death of God, seeing that one disappeared and the other did not. For decades of intense conflict, these two ideologies fought for the primacy of this Niedergang into physiology.

And who fought these ideologies? Basically, the liberal democracies, where, throughout the 20th century, still subsisted some of the old order, something of God’s presence, even if they may not have been aware of it.

I believe that in liberal democracies God has never died, never entirely, precisely because in such democracies there was and is freedom. And where there is freedom there always ends up being a place for God. Therefore, the concept of freedom is absolutely central to Christianity. Freedom and the verb to free appear dozens of times in the New Testament. In the body of liberal democracies, a conservative heart sill beat, where faith, the vertical notion of the human being, the notion of transcendence, still flowed.

This liberal-conservative amalgam, that is, liberal democracies with liberal economies but with hearts tied to the divine order was the backbone of the West, which allowed it to conquer Nazi-Fascism and then to face Communism from 1945 onwards. Throughout the entire Cold War, this apparently unconnected, incoherent, and a little chaotic model of the fusion between liberalism and Christian conservatism ended up prevailing against the totalitarian model of pure physiologism. And we really tend to forget this conservative heart of the West during the Cold War. Ronald Reagan was an epitome of that amalgam—with Reaganomics and all his liberal impulse, he was also a man of profound faith, who put that faith across in his political conception of the fight against the socialist world, which he, unlike his predecessors, had no qualms about calling evil, absolute evil.

Another important figure at that time, which we also tend to forget, is Pope Saint John Paul II, who had a political role in overcoming that physiological enemy, Communism, from his profound faith. I had the opportunity to speak briefly about the connected character of those two dimensions of John Paul II’s actions when I was in Poland, a short while ago.

The problem is that, after 1989, with that very victory of the West, of that liberal-conservative front, someone thought that conservative heart, the Christian faith, was no longer necessary in the core of liberal democracies. Someone said, “we have won; market economy and representative democracy will now spread throughout the world. No one needs God, this is a relic from the Bronze Age.” They decided to cast God from the heart of liberal society and set God outside, in the cold.

They did not realize it, but Communism had long been preparing to occupy liberal society from inside, with Gramsci’s theory, the Frankfurt School, the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s. And with that opening in the heart of liberal society, to cast out God, the way was clear for cultural Marxism, Gramscianism, however you call it, to occupy the heart of liberal society, which had been left vacant. This is globalism, the moment when communism, physiologism, Gramscianism, whatever you call it, occupies the heart, which had been left empty, of liberal society.

It is interesting, because exactly 100 years go by—an exact century between this moment at the end of Nietzsche’s productive life, the moment of his madness, when he announces himself crucified in 1888, and the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. During this century, liberal society had been, somewhat unknowingly, the bulwark of Aufgang, of the conception of transcendence, of the vertical conception of the human being, as a being not only material, but also spiritual.

Unfortunately, from our viewpoint—from around 1989—liberal society unconsciously gave in to Niedergang, to physiologism, because it thought that the Cold War had been a purely economic dispute and that the victory of the capitalist economic model was all that was necessary for that final victory. It was no victory at all; it was, in a way, a defeat whose effects we are still living right now. The “victors” did not realize that, behind that debate, that dispute between economic and political models, was what Plato called, and Heidegger recalls, gigantomachia peri tes ousias, the gigantomachy, the great battle for the essence of the human being. That was at stake.

French historian and philosopher Marcel Gauchet coined the term “disenchantment of the world” to describe this entire path of democratic society, which gradually, from the 18th century onwards, throws away the idea of God. What was the enchantment of the world? It was precisely the presence of God.

Today, along the debate and seminar, the lecturers will discuss some, maybe all the instruments of that insertion of physiologism (let us call it that, to continue using the term) into the heart of liberal society, which, from my viewpoint, constitutes the definition of globalism.

A New Religion, An Ironclad Moralism

To mention some of the instruments we have identified: linguistic deconstruction, maybe the main one, which is the separation between word and reality, which might also be called “nominalism” (though it is not exactly the concept of the medieval philosophy of nominalism) but anyway, the elevation of some concepts, some words to an absolute character to the point where there is no dialogue with reality.

Gender ideology, what I call racialism, which is the conception of society divided into races, the return—something so deplorable—of the concept of race as a cornerstone of society.

And ecologism (to distinguish from ecology) which is ecology made into ideology. That is another example where an area of activity, of thought, loses contact with reality and becomes something that extrapolates it, something abstract which is no longer an object for debate, which must be implemented without debate. So it is fundamental to make that distinction between ecology, or the environmental dimension in its legitimate character, and ecologism, environmentalism as an ideology.

All of those instruments presuppose the absence of God, presuppose the horizontality of the human being. And, simultaneously—something that Nietzsche foretold—they create a new morality, an ironclad moralism, a mechanism for psychological oppression.

Nietzsche predicted that in this development of nihilism, it would not lead to an absence of morality but rather to an attempt at recovering morality without any basis in a divine or structured order. It is curious, because what we are experiencing from these movements—movements that supposedly emerged from libertarian or liberal thinking—is progressively more oppressive. There are things you cannot say, things you cannot do, a moralism even in sexuality. Today a man looking at a woman is tantamount to attempted rape. This is a much stricter moralism than the sort that was criticized during the Victorian era of the 19th century.

Globalism tries to create, in a clumsy way, a sort of new religion with those pseudo-values. Even legitimate concepts such as human rights, tolerance, and environmental protection have been extrapolated into pernicious ideologies. This is an answer to the desert of values rising from this advance of nihilism, where the concept of purpose, the concept of unity, and the concept of truth have been lost.

It’s also a Nietzschean trilogy. He said this would happen, that these three pillars of the previous conception, of morality based on a divine concept, would be lost. And globalism begins to invent false enemies to defend something, to feel that it is defending something, and to give itself some sense of purpose, unity, and truth.

But here is the problem with that creation of a globalist pseudo-religion: it all presupposes that man, the human being, is the measure of all things. It presupposes a sort of humanism. But, in doing so, globalism realizes it is cracking open the door for some sort of return of God, because setting man up as a supreme value leads one to the question of where that supreme value originates. It can only come from above, and globalism cannot admit to that.

It is curious because it creates a strange humanism, one that belittles man and equates him with a machine. So it is interesting, what we see today, with all the discussion of artificial intelligence, in which we normally hear that artificial intelligence is a machine learning to think like a human being. In fact, what happens is the opposite—and that is the globalist plan. Human beings are learning to think like machines. Globalism requires mechanization of the human being. Singularity theoreticians say this would be the moment when artificial intelligence surpasses human intelligence. Ray Kurzweil, an American writer, says this will probably take place around 2045—that is, roughly at the end of Nietzsche’s 200 years.

I believe we are approaching this, but in reality it will not be the moment that a machine will learn to think like man, but rather the moment when we will become subjugated to our own mechanist conception of the very human thought.

The Return of God?

I believe we are right now at a moment of recomposing and awareness of what is at stake, what is that gigantomachy and how we are behaving in face of it.

So, what is the big picture I am trying to draw here? We begin from the concept that God is dead; then comes physiologism as a philosophical structure, let us put it this way, of organization of a society without God. Two ideologies based on that arise. They fight, and only one of them survives. The liberalism that stands up to them, because it maintains a core of faith and anthropotheism, that liberalism with God at its center at first triumphs over physiologism, but believes it to be a purely economic triumph and casts God out from its core.

Then arises globalism, which is nihilism, basically. Globalism is the consolidation of that nihilism foretold by Nietzsche. It is the atheist liberal society submitted to the control mechanisms of that Gramscian, Communist, or physiologist core, whatever we choose to call it.

And we may be entering a new moment, a pivoting moment in this conflict between Aufgang and Niedergang, when we try to reintroduce God into this citadel of liberal society, replacing that atheist religion of the politically correct.

I believe a symbolic moment of that movement—a movement in which Brazil has a fundamental role—was the last World Economic Forum in Davos, where President Jair Bolsonaro, at the end of his opening speech, mentioned God. I am not sure, I did not research it, but I think it was probably the first time a head of state used the word “God,” believing in Him, at the Davos Forum.

I picture the people there having to search the dictionary, “What does that name mean?” in a true moment of disconcert.

And I think that’s it, this is the moment we are living, it is God at Davos. We are entering the citadel to try and recover that heart of liberal society, to try to remake the liberal-conservative amalgam which was what enabled, over the course of the last 150 years, the preservation of a deep concept of human dignity, of the human being as, of course, an earthly being, but one that interacts with the spiritual world, that interacts with God, and not that crushed, horizontal being that soon, if we allow it—and we will not—will start to think like a machine.

That’s it: God at Davos.

Editor’s note: This article was adapted from an essay published in Brazil’s Cadernos de Política Exterior (Foreign Policy Journals) in August. The text is based on a conference given during the seminar on globalism, conducted on June 10, 2019, in Brasilia. Watch the conference here.