Writing in the December 1991 issue of Academic Questions, Fred Siegel, associate professor of history at Cooper Union and a self-described liberal and Democrat, bemoaned a fashionable trend in history writing. The “New Historians,” he quipped, saw American life as “a story of defeat, despair, and domination. American history became a tragedy in three acts: what we did to the Indians, what we did to the African-Americans, and what we did to everyone else.”

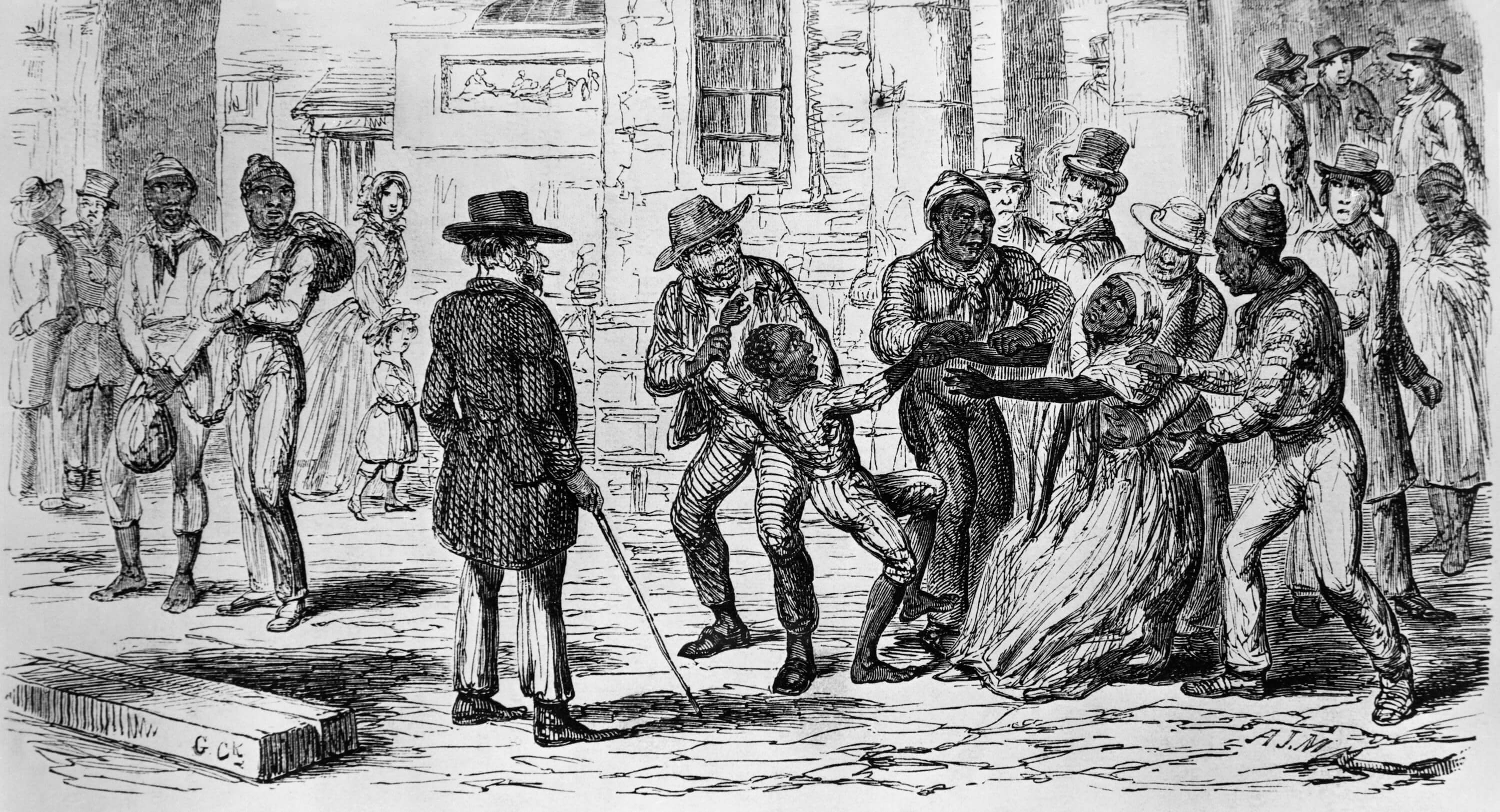

That’s a pretty fair description of A People’s History of the United States. Howard Zinn winds up Act 1 of his book on the oppression of Indians and women only to launch into Act 2 on slavery—beginning with an eight-line description from J. Saunders Redding’s 1950 They Came in Chains of the ship carrying the first slaves to the colonies in 1619: “a strange ship, indeed, by all accounts, a frightening ship, a ship of mystery . . . . through her bulwarks black-mouthed cannon yawned. The flag she flew was Dutch; her crew a motley. Her port of call, an English settlement, Jamestown, in the colony of Virginia . . . . her cargo? Twenty slaves.”

They Came in Chains was the work not of an historian, but of a Hampton Institute English professor. Arna Bontemps, in Saturday Review, described it as “a deeply felt, sometimes impassioned account,” “a fever chart of rising and falling hopes.” Zinn quotes from this dramatic description to set up his own contention that “there is not a country in world history in which racism has been more important, for so long a time, as the United States. And the problem of ‘the color line,’ as W.E.B. Du Bois, put it, is still with us.” In light of America’s uniquely horrible racism, Zinn wonders, “Is it possible for whites and blacks to live together without hatred?”

The Lure of Romanticism

As usual, capitalism is the culprit. Zinn plays fast and loose with numbers and sources in his effort to prove that capitalism is at the root of racism. He misreports and distorts the slaves’ truly horrific suffering for his own purposes. For example, he claims that “perhaps one of every three blacks transported overseas died”—allowing the “perhaps” to do a lot of work. In fact, according to the best quantitative evidence, 12 to 13 percent of slaves died in transit from Africa to the Americas during the history of the Middle Passage. Sometimes a larger percentage of the slave ship’s crew died on the voyage. In the Dutch slave trade, one in five crewmen died at sea. But it suits Zinn’s purpose to exaggerate the true numbers and to ignore the historical context of a time and place when life was more perilous for all.

Zinn acknowledges that slavery existed in Africa—where, in fact, it predated the discovery of America—but presents it as a kinder, gentler kind of slavery: “Slavery existed in the African states, and it was sometimes used by Europeans to justify their own slave trade. But…the ‘slaves’ of Africa were more like the serfs of Europe—in other words, like most of the population of Europe.” The difference was the still-powerful “tribal life” of Africa: “Africa had a kind of feudalism, like Europe based on agriculture, and with hierarchies of lords and vassals. But African feudalism did not come, as did Europe’s, out of the slave societies of Greece and Rome, which had destroyed ancient tribal life. In Africa, tribal life was still powerful, and some of its better features—a communal spirit, more kindness in law and punishment—still existed. And because the lords did not have the weapons that European lords had, they could not command obedience as easily.”

Here Zinn is simply romanticizing life in pre-colonial Africa—just as he romanticized life in pre-colonial America. “Tribal life,” as Zinn presents it, was “communal” and gentle in “law and punishment.” In contrast, “American slavery” is categorically “the most cruel form of slavery in history.” For his account of slavery and the Middle Passage, Zinn relies on Basil Davidson’s 1961 The African Slave Trade. Davidson did do groundbreaking work in the field of pre-colonial African history. But by 1971, well before Zinn published his People’s History in 1980, many of his generalizations were coming under fire from specialists in African history. Zinn didn’t care enough to keep up with the literature. It might have interfered with his desire to indict capitalism: “African slavery is hardly to be praised,” Zinn concedes. But it lacked “the frenzy for limitless profit that comes from capitalistic agriculture; the reduction of the slave to less than human status by the use of racial hatred, with that relentless clarity based on color, where white was master, black was slave.” The real problem between blacks and whites in America wasn’t so much slavery itself—owning other human beings as chattels—but “class exploitation.”

Thus, the Civil War was a tragic missed opportunity. If only it had been fought to overthrow the capitalist system that undergirded the particularly cruel American form of slavery, it might have ended racism (not to mention, presumably, ushering in a worker’s paradise). But sadly, the Civil War, as Zinn presents it, was fought “to retain the enormous national territory and market and resources.”

Histories in the Soviet Union airbrushed certain facts, as they did certain personages from photographs. Howard Zinn does the same thing, airbrushing out evidence that contradicts his claims.

So why did such an evil, capitalist system fight a bloody war to end slavery? After all, within the capitalist system, slavery was profitable: it “remained a profitable investment at the time it was abolished regardless of country,” write Robert Paquette and Mark M. Smith. So there was something beyond the profit motive that ended slavery in the West. Yes, within the capitalist country that Zinn condemns, slavery was killed for moral reasons. As early as the American Revolution, the fight for liberty inspired debates about slavery. Then, by the early nineteenth century, the slave trade had been abolished in England and the United States and the American abolitionist movement was in full swing. Abolitionists were arguing against slavery from Christian and Enlightenment principles (and some, wrongly, on economic grounds). Yet, in 1842, when the Sultan of Morocco was asked by the British consul-general what his country was doing to abolish slavery or to reduce its trade, he replied that he was “not aware of its being prohibited by the laws of any sect.” Indeed, the question was absurd to him. Why would anyone even ask such a thing? The sultan thought that the rightness of slavery “needed no more demonstration than the light of day.”

In fact, the campaign to abolish slavery was a Western thing and a relatively new thing at the time. As the late great Orientalist historian Bernard Lewis put it, “The institution of slavery had . . . been practiced from time immemorial. It existed in all the ancient civilizations of Asia, Africa, Europe, and pre-Columbian America. It had been accepted and even endorsed by Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, as well as other religions of the world.” And it was not only African peoples who were enslaved. Slavery was “a ubiquitous institution” in the early modern period, writes Allan Gallay. “Contemporary to the rise of African slavery in the Americas, millions of non-African peoples were enslaved.” These included “over a million Europeans . . . in North Africa, and perhaps more in the Ottoman Empire,” as well as the European settlers taken in captivity in the New World by Indians—not to mention the enslavement of Indians by Indians of other tribes.

The Civil War not only led to the emancipation of American slaves but inspired leaders in the slave-holding nations of Cuba and Brazil to take steps to end slavery and avoid a similar outcome. The Civil War also had an impact in Europe, where it brought “the issue of slavery sharply before European opinion.” It “coincided with a renewed and determined British effort, by both diplomatic and naval action, to induce Muslim rulers in Turkey, Arabia, and elsewhere to ban, and indeed suppress, the slave trade,” writes Lewis.

As If Nobody Understood the Evils of Slavery

A People’s History does not provide such a historical and global context. Instead, Zinn’s reader gets the impression that American capitalism produced the cruelest slavery in the world—and that Americans invented racism. Zinn blames “the new World” for the development of racial hatred, which he pretends did not exist before the discovery of America. “Slavery,” he claims, “developed quickly into a regular institution, into the normal labor relation of blacks to whites in the New World. With it developed that special racial feeling—whether hatred, or contempt, or pity, or patronization—that accompanied the inferior position of blacks in America for the next 350 years—that combination of inferior status and derogatory thought we call racism.”

In fact, racism is not an invention of Western culture. Let’s consider Zinn’s pseudo-philosophical claim: “This unequal treatment, this developing combination of contempt and oppression, feeling and action, which we call ‘racism’—was this the result of a ‘natural’ antipathy of white against black?” This is a rhetorical question. Zinn suggests that if “racism can’t be shown to be natural, then it is the result of certain conditions, and we are impelled to eliminate those conditions.” So, Zinn claims, “All the conditions for black and white in 17h-century America were . . . powerfully directed toward antagonism and mistreatment.”

These “conditions” have everything to do with capitalism and class. Zinn tells us, “There is evidence that where whites and blacks found themselves with common problems, common work, common enemy in their master, they behaved toward one another as equals.” He cites Kenneth Stampp’s claim that “Negro and white servants of the seventeenth century were ‘remarkably unconcerned about the visible physical differences.’ Black and white worked together, fraternized together. The very fact that laws had to be passed after a while to forbid such relations indicates the strength of that tendency.” So once the proletariat—black and white—unite again, racism will be eliminated.

Histories in the Soviet Union airbrushed certain facts, as they did certain personages from photographs. Zinn does the same thing, airbrushing out evidence that contradicts his claims. But the facts show that racism has existed all over the world, not only in the West, and that it was not only in the West that blacks were singled out for slavery of the most demeaning kind. Nor was racism only directed against those with darker skins.

The Muslim role in slavery and the slave trade is ignored by Zinn, but, in fact, it was “through the Moslem countries of North Africa” that “black slaves were imported into Europe during the Middle Ages.” By “the end of the eighteenth century,” the Islamic Middle East held “the majority of the world’s white chattel slaves.” Whites to the north and blacks to the south were both seen as inferior and therefore legitimate slave material. As Bernard Lewis points out, “The literature and folklore of the Middle East reveal a sadly normal range of traditional and stereotypical accusations against people seen as alien and, more especially, inferior. The most frequent are those commonly directed against slaves and hence against the races from which slaves are drawn—that they are stupid; that they are vicious, untruthful, and dishonest; that they are dirty in their personal habits and emit an evil smell.”

The Arabs, like many in the West, held stereotypes about black men and women as highly sexed. When blacks appear in Islamic illustrations of “court life, domestic life, and various outdoor scenes,” they are depicted doing the lowly tasks assigned to them—“carrying a tray, pushing a broom, leading a horse, wielding a spade, pulling an oar or a rope, or discharging some other subordinate or menial task.” Slaves had limited rights under Islamic law, but it did not mean that they had equal opportunities—even within the institution of slavery itself.

When white slaves were available—before the Russians put up barriers—black slaves usually held positions below them. The Ottoman Empire had at first acquired slaves from Central and Eastern Europe and by raiding “the Caucasians—the Georgians, Circassians, and related people.” These sources dried up when Russia annexed Crimea in 1783 (a shipping off point for the slaves) and conquered the Caucasus in the early nineteenth century. The Ottomans then went to Africa, and by the nineteenth century that continent provided “the overwhelming majority of slaves used in Muslim countries from Morocco to Asia.” Once white slaves were no longer available, black slaves sometimes “were given tasks and positions which were previously the preserve of whites.”

Some of the worst suffering came when Arab slave traders transported slaves, as Thomas Sowell notes in Ethnic America: A History. The “massive commercial sales of Negro slaves began after the conquest of northern Africa by the Arabs in the eighth century,” when “Arab slave traders penetrated down into the center of Africa and on the east coast.” With the “cooperation” of local tribes, “they captured or purchased slaves to take back with them across the Sahara Desert, which eventually became strewn with the skeletons of Negroes who died on the long march. . . .” Sowell comments, “The Arabs were notable as the most cruel of all slave masters.”

The suffering continued into the 19th century as slave traders went into more remote areas as “scrutiny” by the Ottoman Empire and European powers increased. In 1849, sixteen hundred black slaves died of thirst as they were driven from Bornu to southern Libya.

In the 19th century, it was Africa that provided highly prized slave eunuchs. Between 100 to 200 boys between the ages of 8 and 10 were castrated “every year at Abu Tig in Upper Egypt, on the slave caravan route from the Sudan to Cairo.” The castrated boys could be sold at twice the normal price. As Louis Frank wrote in 1802, “it is this increase in price which determines the owners, or rather usurpers, to have some of these wretches mutilated.” These atrocities took place thousands of miles from American shores.

Muslim nations’ adherence to Islamic law, which sanctions slavery (except of free Muslims), made it more difficult to eliminate. As Bernard Lewis explains, “From a Muslim point of view, to forbid what God permits is almost as great an offense as to permit what God forbids—and slavery was authorized and regulated by the holy law.” Most Muslim states did not enact slavery abolition until the years between the World Wars. Yemen did so only when it became a “newly established republican regime” in 1962; that same year, Saudi Araba did, as well, “by royal decree.” The last Muslim country to abolish slavery was Mauritania in the year Zinn’s book came out, 1980.

Zinn chose not to include such information, but instead limited his discussion to earlier centuries of the Atlantic slave trade. He does admit that slaves were captured “in the interior” of Africa—frequently by blacks. Yet the African slave traders are absolved of responsibility. They were “caught up in the [Atlantic] slave trade themselves.” And yet, Bernard Lewis quotes a ninth-century writer who observed that “the black kings sell blacks without pretext and without war.”

Far from being hapless victims lured into a new kind of commerce, the Africans’ legal system actually “fueled the Atlantic slave trade,” according to Boston University professor John Kelly Thornton in Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400–1680, published by Cambridge University Press. And while slaves in America and Europe “typically had difficult, demanding, and degrading work, and they were often mistreated by exploitative masters who were anxious to maximize profits,” in Africa a slave could be arbitrarily sacrificed on an altar.

Although the English colonies, and then the United States, accounted for a relatively small percentage of the purchases of African slaves in the New World, they “held the largest number of slaves of any country in the Western hemisphere—more than a third of all the slaves in the hemisphere—in 1825.” The reason was that it was “the only country in which the slave population reproduced itself and grew by natural increase. In the rest of the hemisphere, the death rate was so high and the birthrate so low that continuous replacements were imported from Africa.”

An American Distinction

The life of a slave was full of uncertainty, subject to the owner’s whims and circumstances, to be sure. Cruel punishment was meted out arbitrarily and family members could be sold without warning, as Thomas Sowell acknowledges. Yet he also states that conditions were “generally more brutal in other countries” than in the United States (in contrast to Zinn’s claim of the opposite). Thornton provides some sample cases—including the Ridgley estate in mid-seventeenth-century Maryland—where slaves could raise crops on a portion of the estate and sell them in exchange for some of the profits. Virginia slave John Graweere raised pigs and sold them for “one half the increase.”

American slaves were sometimes given their legal freedom or partial freedom, such as the “half freedom” of Dutch areas. “In these situations, clearly, slaves had some mobility and could form families and socialize their children. That they might not choose to forget their African background is revealed in the fact that one of the most successful of these small-holding former slaves, Anthony Johnson, named his farm ‘Angola,’” according to Thornton. Their culture was changed, to be sure, partly because slaves from various African cultures were thrown together. There is evidence that even on slave ships and during the Middle Passage new cultural relationships were formed between Africans of different societies. The result was a new culture, with “the many and varied African cultures” serving as “building blocks” and European culture providing “linking materials.”

Many slaves adopted the ideals of Western culture, including Frederick Douglass, the great abolitionist. Zinn quotes Douglass several times—but as is to be expected, selectively. The discussion of Douglass’s autobiography comes on the heels of that of another black abolitionist, David Walker, the “son of a slave” from whose pamphlet, Walker’s Appeal, Zinn quotes extensively, adding his own comment, “There was no slavery in history, even that of the Israelites in Egypt, worse than the slavery of the black man in America, Walker said.” While we might sympathize with Walker’s cause, we should also remember that he was writing not history, but polemic.

Douglass’s autobiographies, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave first published in 1845, and My Bondage and My Freedom from ten years later, offer not only an account of a firsthand experience of being a slave, but also a more nuanced investigation of the institution. Zinn’s discussion of this classic begins, “Some born in slavery acted out the unfulfilled desire of millions. Frederick Douglass, a slave, sent to Baltimore to work as a servant and as a laborer in the shipyard, somehow learned to read and write, and at twenty-one, in the year 1838, escaped to the North, where he became the most famous black man of his time, as lecturer, newspaper editor, writer.” Douglass also described the differences between the treatment of slaves in urban areas and on isolated plantations, where the slave owner was far enough from his neighbors that they did not hear “the cries of his lacerated slave” or see how ill-fed or clothed he was.

Zinn presents anything short of immediate utopian results as evidence of hypocrisy and greed. Any suggestion that injustices should be cured by changes that are gradual, and lawful—and safe—is taken as evidence of insincerity.

In the first edition of the Narrative, Douglass, clearly hoping to inspire antislavery sentiment, described the beatings and hunger he and others endured, the abandonment of his aged grandmother as the property was divided up upon the death of the original owner, and men selling off the children they had fathered with slave women. Douglass was also careful to explain how the institution of slavery transformed inherently good people, like his mistress, who changed for the worse after her husband pressured her to treat the eight-year-old Douglass like a slave, in a dehumanizing manner. The “poison of irresponsible power,” Douglass wrote, “commenced its infernal work. That cheerful eye, under the influence of slavery, soon became red with rage. . . .” In his writings and his speeches, Douglass appealed, against the institution of slavery, to the ideals of the Bible and the Declaration of Independence. He repeatedly pointed to the inconsistency between the treatment of slaves and the precepts of Christian charity and the American ideals of liberty and equality. These principles were irrelevant, of course, to the Sultan of Morocco around that same time.

The climactic moment of the Narrative comes when the 16-year-old Douglass fights back against Edward Covey. After enduring weekly beatings for six months and facing more punishment for having fainted from overwork, Douglass fought off Covey and an assistant as the infamously cruel “breaker” of slaves was attempting to tie him up. Douglass described the “battle” as the “turning-point in my career as a slave,” because it “rekindled the few expiring embers of freedom, and revived within me a sense of my own manhood.”

This kind of spirit was not unusual among slaves. Douglass showed incredible will, but many slaves practiced other forms of resistance, with “work slowdowns, sabotage, and running away,” depending upon the circumstances, which varied. As the 1960s and 1970s brought greater interest in black history, scholars such as Edgar McManus, in his A History of Negro Slavery in New York, countered the stereotype of “Negroes as a passive mass, harnessed and driven by a white elite.” McManus pointed out that in New Netherland, prejudice was more religious than racial in nature. While Jews could not “own realty” or join the militia, “Negroes could.” Some even “owned white indentured servants” and “intermarried with whites.” Although slaves engaged in domestic and farm work, they were also employed as skilled workers—goldsmiths, naval carpenters, coopers, tanners, and masons.

As Lorena Walsh points out, the discussions about liberty in the years leading up to and during the War of Independence affected slave owners and slaves. It also affected slave status. Loyalists and Patriots vied for slaves’ allegiance by promising them freedom and had their own authority compromised when they employed slaves. Over four thousand blacks “served in the Continental Army, and thousands more in the local militia.” Those serving from New York State enjoyed the prospect of freedom, thanks to a law passed by the New York State Assembly in 1781. Nearly all the Revolutionary War leaders were inspired to condemn slavery. In fact, “Jefferson’s first draft of the Declaration of Independence contained a sweeping condemnation of the slave trade and England’s refusal to allow legislation ‘to prohibit or restrain this execrable commerce.’” Washington, Jefferson, and Madison—all slaveholders—expressed support of “gradual emancipation.”

Zinn acknowledges this passage in the original Declaration, but then casts suspicion upon Jefferson’s motives: “This seemed to express moral indignation against slavery and the slave trade (Jefferson’s personal distaste for slavery must be put alongside the fact that he owned hundreds of slaves to the day he died.)” And Zinn suggests a possible self-serving motive: the fear of slave insurrections. “Because slaveholders themselves disagreed about the desirability of ending the slave trade,” Zinn writes, “Jefferson’s paragraph was removed.” Zinn concludes with dripping sarcasm, “So even that gesture toward the black slave was omitted in the great manifesto of freedom of the American Revolution.”

As usual, Zinn presents anything short of immediate utopian results as evidence of hypocrisy and greed. Any suggestion that injustices should be cured by changes that are gradual, and lawful—and safe—is taken as evidence of insincerity. No credit is given to such American Founders as John Jay, Alexander Hamilton, and Philip Schuyler for their roles in the newly formed New York Manumission Society, organized in 1785, which became the “working organization of the antislavery movement,” keeping the pressure up “on state officials” and “the issue before the public”—and that ultimately succeeded in phasing out slavery in New York State.

Full abolition was achieved in 1827.

Realities, Then and Now

There is still slavery in Africa to this day. “[A]n estimated 9.2 million” Africans “live in servitude without the choice to do so” at “the highest rate. . . . in the world,” according to the 2018 Global Slavery Index. Slavery is “especially prevalent” in Eritrea and Mauritania, countries noted for the collusion of the government in the practice. In Eritrea, the “one-party state of president Isaias Afwerki has overseen a notorious national conscription service” for forced labor. In Mauritania, “the world’s last country to abolish slavery,” “the situation is more acute,” with the “black Haratin group” inheriting its slave status.

In 2018, photojournalist Seif Kousmate traveled to Mauritania, where he was imprisoned for a time. His photos of the Haratine in Mauritania, published at the Guardian, are images of abject poverty and misery. Mauritania is a place where “up to 20 [percent] of the population is enslaved, with one in two Haratines forced to work on farms or in homes with no possibility of freedom, education or pay.” And contrary to Zinn’s assertion that racism is a uniquely American trait, Kousmate writes, “For centuries, Arabic-speaking Moors raided African villages, resulting in a rigid caste system that still exists . . . with darker-skinned inhabitants beholden to their lighter-skinned ‘masters.’” Many of the subjugated can conceive of no other system and accept their status. The government, however, “denies that slavery exists,” and “prais[es] itself for eradicating the practice.”

As Zinn was writing A People’s History, Mauritania had not yet made slavery officially illegal. Yet, Zinn obscures the practice of slavery in other parts of the world besides America—in the past and in his present—and focuses on American slavery, falsely presenting American slavery as the most cruel, and America as the most racist. He preemptively discounts statistical evidence to the contrary. For example, he writes, “Economists or cliometricians (statistical historians) have tried to assess slavery by estimating how much money was spent on slaves for food and medical care.” But then, to keep the reader from paying any attention to this evidence, Zinn immediately asks, “But can this describe the reality of slavery as it was to a human being who lived inside it? Are the conditions of slavery as important as the existence of slavery [emphasis in the original]?” The suggestion that they’re not, however, contradicts Zinn’s earlier excuse-making for African slavery, when he argued that the conditions of slavery there under their pre-capitalist society—“tribal life,” “a communal spirit”—made the existence of slavery not so bad.

Zinn’s aim is to present all American slave owners as wicked Simon Legree. So, he brings up the whipping of slaves “in 1840–1842 on the Barrow plantation in Louisiana with two hundred slaves.” Zinn quotes from Time on the Cross by Robert William Fogel and Stanley Engerman: “The records show that over the course of two years a total of 160 whippings were administered, an average of 0.7 whippings per hand per year. About half the hands were not whipped at all during the period.” Zinn adds an editorial note: “One could also say: ‘Half of all slaves were whipped.’ That has a different ring.” Zinn also points out that though “whipping was infrequent for any individual,” nonetheless “once every four or five days, some slave was whipped [emphasis in the original].”

Zinn claims that the amount of cruel physical punishment on Barrow’s plantation was typical because “Barrow as a plantation owner, according to his biographer, was no worse than the average.” But do we know what “average” is? Zinn has presented only one isolated case.

In another case of selective reporting, Zinn tells his readers, “A record of deaths kept in a plantation journal (now in the University of North Carolina Archives) lists the ages and cause of death of all those who died on the plantation between 1850 and 1855.” Zinn doesn’t tell his reader what plantation these numbers are from, but he does report the ages: “Of the thirty-two who died in that period, only four reached the age of sixty, four reached the age of fifty, seven died in their forties, seven died in their twenties or thirties, and nine died before they were five years old.” Those certainly seem like young ages, but they are records from only one plantation—which for all we know was chosen by Zinn precisely for the short life-spans of slaves there.

Comparative statistics tell a very different story. Nobel Prize-winning economic historian Robert William Fogel has shown that American slaves were better nourished than many other groups, including “most European workers, during the nineteenth century.” At that time, “all of the working classes . . . probably suffered some degree of malnutrition,” in comparison to modern standards. The malnutrition of American slaves was not “as severe as that experienced by . . . Italian conscripts, or the illiterate French conscript,” he writes. Height is an indicator of nutrition, and slaves born in the United States were “about an inch shorter than U.S.-born whites in the Union Army,” but “taller than French and Italian conscripts, British town artisans, and British Royal Marines.” No wonder Zinn wants his reader to disregard the findings of “[e]conomists and cliometricians.” It better serves his purpose to discount and rely on isolated, misleading examples, instead.

Consider the sources provided by Zinn: a diary kept by a plantation owner identified only by last name and state, and an unidentified plantation journal in the “archives” at the University of North Carolina. Can we find a grosser violation of the American Historical Association’s standards for evidence? As if this weren’t bad enough, Zinn then refers to “two northern liberal historians” who he says authored the “1932 edition of a best-selling textbook.” That unnamed book by unnamed authors allegedly excuses slavery “as perhaps the Negro’s ‘necessary transition to civilization.’” Who are the straw men who are supposed to have made this appalling observation? We have no way of knowing, so we can’t check Zinn’s accusations.

Zinn switches back and forth from presenting untraceable isolated incidents, to discounting rigorous statistics, to posing leading questions: “But can statistics record what it meant for families to be torn apart, when a master, for profit, sold a husband or a wife, a son or a daughter? In 1858, a slave named Abream Scriven was sold by his master, and wrote to his wife: ‘Give my love to my father and mother and tell them good Bye for me, and if we Shall not meet in this world I hope to meet in heaven.’” In the face of such human suffering, which was very real, only a heartless cliometrician could be interested in actual data—so let’s not worry about the documented facts.

Such forced family break-ups did happen to an estimated third of slave families—as conservative historians have acknowledged—and they were horrific. Abolitionist writers, including Frederick Douglass, pointed to such inhumane practices to appeal for abolition, and Americans came to see slavery as wrong.

The arguments that persuaded Americans to end slavery are grossly distorted by Zinn. Take Frederick Douglass’s July 5, 1852, speech in Rochester, New York: “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?” Zinn quotes from the early part of the speech which was intended to arouse the emotions of the audience, to make them empathize and understand the hypocrisy of celebrating the Declaration of Independence in a nation that denies freedom to slaves. But, not surprisingly, he ignores the patriotic climax of the speech. Thus, the only idea that Zinn takes away from it is that the “whole nation” was “complicit” in the “shame of slavery.” Zinn spares readers the passage in which Douglass expresses faith in the Constitution, calling it a “glorious liberty document.” Those caps are in the original speech by Frederick Douglass, who had actually broken with fellow abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison over Garrison’s abandonment of faith in the Constitution and the American system. At the climactic moment of the speech, Douglass declared, “I hold there is neither warrant, license, nor sanctions of the hateful thing [for slavery, that is, in the Constitution]; but, interpreted as it ought to be interpreted, the Constitution is a glorious liberty document.” Contrary to Zinn’s representation, Douglass’s speech expressed his optimistic faith in America. “I do not despair of this country,” Douglass proclaimed, expressing confidence that “the doom of slavery is certain.” His “spirit” was “cheered” by “drawing encouragement from the principles of the Declaration of Independence . . . and the genius of American Institutions. . . .”

Zinn quotes Douglass at length, though always selectively, but he says nothing about Douglass’s role in the Civil War—the war that Zinn casts as simply a means to perpetuate a racist capitalistic state. In fact, Douglass served as a recruiter of black troops—Douglass’s own sons served in the war—and as an adviser to President Lincoln. Zinn also fails to mention the appointment of this stalwart Republican to political office as federal marshal (1877–1881), recorder of deeds for the District of Columbia (1881–1886), and chargé d’affaires for Santa Domingo and minister to Haiti (1889–1891).

Zinn ignores Douglass’s relationship with Lincoln so that he can portray the president as a cowardly racist politician beholden to powerful money interests. To Zinn, Abraham Lincoln “combined perfectly the needs of business, the political ambition of the new Republican party, and the rhetoric of humanitarianism.” Lincoln used abolition for political advancement. It was only “close enough to the top” of his “list of priorities” that “it could be pushed there temporarily by abolitionist pressures and by practical political advantage.” Zinn contrasts Lincoln’s statement “that the institution of slavery is founded on injustice and bad policy, but that the promulgation of abolition doctrines tends to increase rather than abate its evils” with “Frederick Douglass’s statement on struggle, or Garrison’s ‘Sir, slavery will not be overthrown without excitement. . . .’”

But Zinn does not tell the reader where the Lincoln quotation is from: a resolution that the future Great Emancipator made when he was a twenty-eight-year-old state house representative. It can be found in one of Zinn’s favorite sources, Richard Hofstadter’s The American Political Tradition, from which Zinn purloins not only quotations, but also Hofstadter’s jaundiced view of Lincoln, whom Zinn excoriates for being concerned about public opinion (imagine that, in an elected official!) and for following the Constitution (!) The only kind of abolitionist Zinn approves of is a violent abolitionist like John Brown, whose “last written statement, in prison, before he was hanged” for the raid on Harper’s Ferry, as Zinn approvingly notes, declared, that “the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood.”

Zinn ignores the fact that Brown’s raid led to the deaths of ten in his party, including two of Brown’s sons, as well as several civilians, including two slaves and a free black man. This was after Brown and his band of men had killed five settlers in Kansas, where the issue of slavery was being contested. The method was to drag “the man of the house from his house and butche[r] him as his family screamed in horror.” These victims were not even slave owners, just settlers who believed in allowing slavery into the territory. Brown succeeded only in sowing fear and mistrust in the South, in the opinion of Thomas Woods. Zinn naturally approves of purging injustices “with blood,” so John Brown is a hallowed martyr to him. A People’s History expresses Zinn’s disappointment that “it was Abraham Lincoln who freed the slaves, not John Brown.”

Lincoln’s original hope to eliminate slavery gradually by beginning to outlaw it in the territories while keeping the nation together is not good enough for Zinn. He prefers Brown’s vigilante terrorism. As Zinn tells the story, Southern states seceded from the Union after Lincoln’s election not because of slavery, but out of “a long series of policy clashes between South and North.”

The clash was not over slavery as a moral institution—most northerners did not care enough about slavery to make sacrifices for it, certainly not the sacrifice of war. It was not a clash of peoples (most northern whites were not economically favored, not politically powerful; most southern whites were poor farmers, not decisionmakers) but of elites. The northern elite wanted economic expansion—free land, free labor, a free market, a high protective tariff for manufacturers, a bank of the United States. The slave interests opposed all that; they saw Lincoln and the Republicans as making continuation of their pleasant and prosperous way of life impossible in the future.

Zinn ignores a little fact: that Lincoln had been elected on an antislavery ticket. The “decisionmakers” were the voters. The “clash” which had been building up for years before his election was over slavery. As one textbook notes, “The causes of secession, as they appeared to its protagonists, were plainly expressed by the state conventions [of the Deep South]. ‘The people of the Northern states,’ declared Mississippi, ‘have assumed a revolutionary position towards Southern states.’ ‘They have enticed our slaves from us,’ and obstructed their rendition under the fugitive slave law. They claim the right ‘to exclude slavery from their territories,’ and from any state henceforth admitted to the Union.”

The North was charged with “‘a hostile invasion of a Southern state to excite insurrection, murder and rapine’. . . . South Carolina added, ‘They have denounced as sinful the institution of slavery; they have permitted the open establishment among them’ of abolition societies, and ‘have united in the election of a man to the high office of President of the United States whose opinions and purposes are hostile to slavery.’” The textbook authors conclude:

On their own showing, then, the states of the Lower South seceded as the result of a long series of dissatisfactions respecting the Northern attitude toward slavery. There was no mention in their manifestoes or in their leaders’ writings and speeches of any other cause. Protection figured as a ‘cause’ in the Confederate propaganda abroad and in Southern apologetics since; but there was no contemporary mention of it because most of the Southern congressmen, including the entire South Carolina delegation, had voted for the tariff of 1857, and because the Congress of the Confederacy reenacted it. . . . or was any allusion made to states [sic] rights apart from slavery; on the contrary, the Northern states were reproached for sheltering themselves under states [sic] rights against the fugitive slave laws and the Dred Scott decision.

The new constitution of the Confederacy stated, “‘Our new Government is founded . . . upon the great truth that the negro is not the equal of the white man. That slavery—subordination to the superior race, is his natural and normal condition.’”

Suddenly, the Left Accepts Confederate Premises

But in Zinn’s history, “Lincoln initiated hostilities.” Oh, really? In fact, Confederate forces fired the first shot of the war. When Confederate forces took over Fort Sumter, Lincoln notified them that he would be sending supplies only, leaving the ball in the court of the Confederates. On April 6, Lincoln notified the governor of South Carolina “to expect an attempt will be made to supply Fort Sumpter [sic] with provisions only; and that, if such attempt be not resisted, no effort to throw in men, arms, or ammunition will be made, without further notice, or in case of an attack upon the Fort.’” On April 12, Confederate forces fired on Fort Sumter.

Zinn is engaging in a kind mental gymnastics. The fact is, Zinn will do anything to make America look bad; he simply cannot allow his reader to give the first Republican elected president credit for freeing the slaves—and for going about it in a principled and prudent manner. That would mean giving the American people credit for abolishing slavery, and it would undermine Zinn’s picture of America as a uniquely racist country.

So, Zinn has to make out that Lincoln’s actions always fall short.

Even the Emancipation Proclamation did not arise out of a sincere desire to free the slaves, but only from political and military expediency: “When in September 1862, Lincoln issued his preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, it was a military move, giving the South four months to stop rebelling, threatening to emancipate their slaves if they continued to fight, promising to leave slavery untouched in states that came over to the North.” The Proclamation made the Union Army open to blacks—but that was just for propaganda purposes: “And the more blacks entered the war, the more it appeared a war for their liberation.”

Was Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation a cynical move? Was it issued only for military advantage and public relations? To the contrary, in issuing the Proclamation, Lincoln put his military powers as commander-in-chief at the service of his moral convictions. That was the only way Lincoln could issue the proclamation. As James Oakes explains:

Lincoln was freeing slaves by virtue of the power vested in the president as commander in chief of the army and navy “in time of actual armed rebellion against the authority and government of the United States, and as a fit and necessary war measure for suppressing rebellion”. . . . Except in time of war or insurrection the Constitution forbade the federal government from directly interfering with slavery in the states where it existed. Military necessity was the only constitutional ground on which Lincoln could justify federal “interference” with a state institution.

James McPherson believes that Lincoln may have been influenced by a pamphlet by William Whiting, a leading lawyer and abolitionist in Boston. In The War Powers of the President, and the Legislative Powers of Congress in Relation to Rebellion, Treason, and Slavery, Whiting had argued “that the laws of war ‘give the President full belligerent’ right as commander in chief to seize enemy property (in this case slaves) being used to wage war against the United States. . . .”

But, as McPherson also points out, Lincoln “recognized with regret that white racism was a stumbling block to emancipation.” Thus, in the months leading up to the Proclamation, he advanced “the colonization of freed slaves abroad.” It was “a way of defusing white fears of an influx into the North of freedpeople.” So, Lincoln met with “five black men from Washington” on August 14, 1862, to “urg[e] them to consider the idea of emigration.”

Zinn ignores Lincoln’s reasons for seeking to send freed blacks to Africa, charging that Lincoln “opposed slavery, but could not see blacks as equals, so a constant theme in his approach was to free the slaves and to send them back to Africa.” He also ignores many efforts to end slavery short of war, claiming, “It was only as the war grew more bitter, the casualties mounted, desperation to win heightened, and the criticism of the abolitionists threatened to unravel the tattered coalition behind Lincoln that he began to act against slavery.” This is false. Lincoln had supported outlawing slavery in the new territories, hoping that that would lead to gradual abolition. And he gave the border states multiple opportunities to accept compensated abolition.

Zinn, who quotes Hofstadter’s claim that the Emancipation Proclamation “had all the grandeur of a bill of lading,” either misses or purposely obscures Lincoln’s intentions and his political genius in promulgating it—for example, in his reply to Horace Greeley’s open letter accusing Lincoln of deferring to “Rebel Slavery.” James McPherson calls Lincoln’s presidential letter a “stroke of genius” in “preparing public opinion” for the Proclamation. McPherson explains that “to conservatives who insisted that preservation of the Union must be the sole purpose of the war, Lincoln said that such was his purpose. To radicals who wanted him to proclaim emancipation in order to save the Union, he hinted that he might do so. To everyone he made it clear that partial or even total emancipation might become necessary . . . to accomplish the purpose to which they all agreed.”

Howard Zinn claims that Lincoln, in his efforts to eliminate slavery, was simply reacting to “abolitionist pressures” and angling for “practical political advantage.” In fact, Lincoln was putting pressure on radical abolitionists—and on opponents of abolition, too—to win the war, preserve the Union, and free the slaves. To achieve those worthy goals, he had to take political risks and exercise his formidable political skills. As Debra Sheffer writes, “Lincoln believed predictions that the proclamation would seriously hurt the Republican Party in the [1862] elections, but he forged ahead with the plan in order to win the war and save the Union. The Republican Party did indeed suffer losses as a result of the proclamation, but the damage was minimal, with Republicans still holding a majority in both the Senate and the House.” Lincoln’s annual address to Congress in December included “one final plea for the Border States to consider emancipation.”

Zinn the Iconoclast

But Howard Zinn is unimpressed. Zinn is determined to knock Lincoln off his pedestal. He wants to replace “Lincoln freed the slaves”—a true fact of history, learned by generations of Americans for a century—with the notion that Lincoln was a small-minded political operator who “skillfully” blended “the interests of the very rich and the interests of the black” and “link[ed these two with a growing section of Americans, the white, up-and-coming, economically ambitious, politically active middle class.”In other words, the Civil War didn’t so much free the slaves as enable bourgeois oppression. Only Zinn could present Lincoln—the American president with the humblest background, a man who worked his way up from poverty and was often ridiculed by the elites—as a member of the elite ruling class. Zinn simply cannot give Abraham Lincoln—and thus the American people who elected him and fought to win the Civil War—credit for ending slavery.

Frederick Douglass saw it differently. In 1876, more than a decade after the president had been assassinated for his anti-slavery position, Douglass said, “Abraham Lincoln was at the head of a great movement and was in living and earnest sympathy with that movement, which, in the nature of things, must go on until slavery should be utterly and forever abolished in the United States.”

Of course, that estimate of Lincoln is not included in A People’s History. And of course, Zinn neither quotes nor even refers to Douglass’s 1865 speech, “What the Black Man Wants”:

What I ask for the Negro is not benevolence, not pity, not sympathy, but simply justice. . . . everybody has asked the question, and they learned to ask it early of the abolitionists, “What shall we do with the Negro?” I have had but one answer from the beginning. Do nothing with us! Your doing with us has already played the mischief with us. Do nothing with us! If the apples will not remain on the tree of their own strength, if they are wormeaten at the core, if they are early ripe and disposed to fall, let them fall! I am not for tying or fastening them on the tree in any way, except by nature’s plan, and if they will not stay there, let them fall. And if the Negro cannot stand on his own legs, let him fall also. All I ask is, give him a chance to stand on his own legs! Let him alone!

For Howard Zinn, it was not a good thing to simply treat former slaves as men, to leave them free to run their own lives. He was unwilling to acknowledge Douglass’s accomplishments in national affairs, preferring to present Douglass as a pitiful and angry militant waiting for a revolutionary leader, and the Civil War as a tragic missed opportunity for a leftist social revolution against the “deeply entrenched system” of capitalism.

For Zinn, the very real horrors of slavery are simply more fodder for his war against America and Western civilization. The nearly three-quarters of a million dead in the Civil War are just casualties of a military machine, and blacks are no better off than they were under slavery. The irony is that, as historian Robert Paquette, a specialist in the history of slavery, has remarked in his criticism of the use of Zinn’s history as a text in high school classrooms:

An assessment in a classroom of, say, the history of slavery— the peculiar institution—by a professional historian should take into consideration the fact that the institution was not peculiar at all in the sense of being uncommon, and that it had existed from time immemorial on all habitable continents. In fact, at one time or another, all the world’s great religions had stamped slavery with their authoritative approval. Only at a particular historical moment—and only in the West—did an evolving understanding of personal freedom, influenced by evangelical Christianity, emerge to assert as a universal that the enslavement of human beings was a moral wrong for anyone, anywhere.

Or as President Lincoln reminded the nation at the dedication of the new cemetery at Gettysburg: the dead had “not died in vain” because “a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal” would “endure.”