D-Day is more than a remembrance of America’s great victory in the Battle of Normandy. It is a celebration of the Greatest Generation and the lessons they have to teach us.

Like Jews repeating the story of the Passover every year for 3,000 years, we must recall the story of this generation’s great deeds, or we will lose some idea of who we are, why we are here, and what we are capable of achieving. Indeed, if we don’t remember what our fathers knew, we will lose our country.

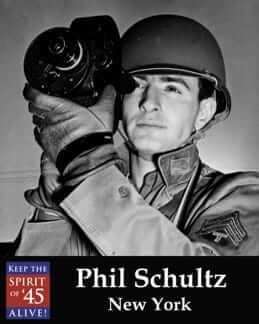

My beloved father, who passed away two years ago at 98-years-old, was a typical member of the greatest generation. Phil Schultz was eternally optimistic, fearless, hard-working, a responsible family man and provider, and patriotic to his core. He achieved the American Dream, not through selfishness or callousness but rather through family loyalty, taking care of those closest to him, and believing in himself. It was the same ability to pull together and have confidence in victory that gave our country the stamina to win World War II, and later let my Dad realize his personal dream of being a professional cameraman.

If only the Millennials and Generation Z could share in his life experiences and wisdom for just a moment, their world would be transformed.

A Quintessentially American Story

Here are the roots of my Dad’s optimism. He was born in a small house with a dirt floor in the Jewish Pale of Settlement in the Soviet Union. His father escaped the Communists, made his way to America, and after several years, had earned enough to bring the family to join him.

My Dad was 9 years old. He excelled in public school and won a place in the Bronx High School of Science, but had to drop out during the Depression to help his family. He never finished school. He did serve in the Civilian Conservation Corps in Oregon as a firefighter and a logger. Back home, he was a self-taught photographer with his gang of Jewish friends in the Bronx, taking girlie pictures and selling them to cheap magazines for a few dollars.

When America entered World War II, my father, armed with his portfolio of photos, signed up immediately. He was assigned to be a combat photographer with the Army Signal Corps.

He soon shipped out to England, to prepare for the Allied invasion of Northern Europe. He was with the 165th Signal Photo Company, 29th Infantry Division. This was the “Band of Brothers” division that took Omaha Beach, the lead troops in the invasion that began on June 6, 1944.

Being a combat photographer meant he served on the front lines of World War II from Omaha Beach to the liberation of Paris, including the Battle of the Bulge, as well as the battle to take the Remagen Bridge that led into Germany and ultimately Berlin.

His films of the action are in the Library of Congress. During the war, they were edited by the Army and shown as newsreels in cinemas across America. Remember, this was before TV, and the images captured by soldiers like my father were how Americans at home could follow the war. It was important in mobilizing the entire country to sacrifice, to work hard for the war effort and to win.

The amazing thing is I have “home photos” of it all, which I found years later when Dad had to move to assisted living and I was closing down my parents’ apartment. There was a small box from a Roliflex camera he had found in a cave in Germany during the war, and it was crammed full of high-quality Leica contact sheets of still photos he and his buddies had taken mostly between the battles.

Here are his few personal photos from Normandy, June 1944, with commentary in his own words.

“At Last, We Are Going After Hitler”

My experiences in World War II, I would say, started way before Pearl Harbor, because I was always extremely anti-fascist, and I knew somewhere along the way we would have to fight, and fight everything that was happening before it. So after Pearl Harbor, I went to volunteer in the Army, even before most of my friends.

As a soldier, we didn’t know when the D-Day invasion was going to come, but there was a feeling—there was such a build-up of American forces . . . all of a sudden, you are almost elbow to elbow with American forces on this island (Great Britain). They were coming over by the boatload and it was more and more of a build-up. Then one day, one day we said, “Alright, pack everything, you have to get on the trucks.”

We got on the trucks in a convoy and we went this way and that way. The roads were dark, and all the signs had been taken down, in case of a German invasion.

I still get a chill, remembering. As far as I could see along the country roads, piles of munitions. The people came out in the dark and watched. They lined the roads. It was so emotional. We didn’t talk in the trucks and it was very emotional. The only talking was maybe, “You got a cigarette?” The emotion. They knew what was happening.

We went to Torquay, which was where we got on the boat. We weren’t gung ho. No, we were scared, because we weren’t experienced. We didn’t know what to [expect]—we hadn’t been under fire. War was movies.

I remember feeling, at last, we are going after Hitler. I was happy because this would open up the second front and end the war and end Hitler. I wasn’t happy, “ha-ha happy,” but it was a very emotional period. We all knew. I and a couple of other guys I was close with said, “Oh boy, this is it.”

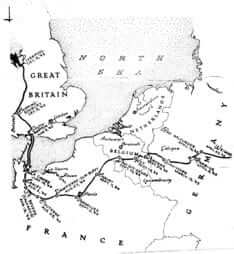

On the truck that night we were told where we were going. We are going to Normandy. They gave us maps, told us where we were going, what our objective was, where we were going to land exactly on the beach, every yard was marked off on the map. They knew where Phil Schultz was going to land, the only thing missing was my name. We were supposed to land about 2 p.m. on D-Day.

We got on the boats that night and fell asleep. I was on a small boat with artillery. The next morning, we first saw where we were. We were not close to shore. We were surrounded by an armada of tens of thousands of ships. We just couldn’t believe it.

Then there was a reading on the ship of Eisenhower’s proclamation and order of the day. What we were supposed to do, to invade this and that.

Before we went off to the invasion, about month or two before, when I was assigned to London. I spent a lot of time with Robert Capa (the older brother of a best friend from the Bronx). He was a war correspondent and he knew he was going to go in with the very first wave. I was supposed to land at 1 or 2. But what happened was that we heard all sorts of rumors that things didn’t go well on the beach. We didn’t go in when we were supposed to and I started to notice small speed boats bringing wounded back to certain ships, and some wounded were brought back to my ship.

I asked permission to go to the beach, because they were going to pick up wounded. I had to promise I wouldn’t go onto the beach. The officer said, “You aren’t landing yet and you can’t land without your unit, so only if you come back.” I did go on the beach and we brought back wounded.

Now the beach— [there] was what you call beach master, this was a Navy guy, the beach master was in charge of this much beach and the boat. And he was standing there with all the artillery. There was a designation for the ships to stop and come and go.

There was a beach master. Fortunately, there was no shelling when I got there. They invaded or started invading about 5-5:30 and when I got there it was 10:30-11:00. And the beach was practically empty because everyone on the beach was laying down, and they were up against the hedgerows where they could not break through yet. So, I got some pictures of the wounded being put on and I went back to my ship and we didn’t land until late, late that day.

The first thing that happened to me when we got on the beach, it was quiet already, I bumped into a United Press correspondent who I knew from London, because of Robert Capa, and the first thing he said was, “Capa is missing.”

I said, “Oh, God!” and the first thing that came to my mind was what am I going to tell Julia, his mother. I was very close to his family, he was like a big brother to me. For three days, I really worried.

I went into Sainte-Mère-Église, which we just captured earlier that day. It was in the movie “The Longest Day,” where the paratrooper got stuck on the steeple. That was the village. It was right on the waterfront practically, just to the right of us. For three days I worried whether Capa . . . I didn’t know it, but before I even got to the beach he got his pictures and he was back in London. He wouldn’t trust his pictures to anybody. He got back on the boat and went back on one of the ships and got himself back to London to the labs to print his pictures.

His darkroom assistant was so excited the negatives were rushed back before the battle was over, that he melted them in his haste, and only a few images survived.

From then on things are kind of blurry. We fought for weeks in the hedgerows.

In the battle for Saint-Lô, we were under such heavy artillery fire I wouldn’t—couldn’t—I was afraid to stand up. I was crawling in a tank rut and knew I’d be hit any minute. You felt like every shell was coming straight at you. There was a French farmer’s body in the trench and I crawled right over it. All of sudden I hear, “You can’t get pictures that way soldier.”

I looked up. It was General Cota I’d been assigned to take photos of him in England, when he went to visit Lady Astor. (He was played by Robert Mitchum in “The Longest Day.”) He was walking along under fire. But he got hit—shrapnel in the shoulder. An hour later, I was taking pictures of him getting a medal.

By August, the road was open to Paris. We stopped for the 2nd French. Eisenhower thought the 2nd French Armored Division attached to the American Army should have the honor of marching in and taking Paris. So we were off now to Paris and every photographer in the Army, no matter where they were, attached themselves to the 2nd Army Division. We were advancing 20, 30, 40 miles a day and there was nothing to hold us back and the only thing in front of us was Paris.

I hooked up with Capa again, and we came to the town of Rambouillet and there was Hemingway with his own private army of free French, marching them up and down.

We go into Paris. It is so unbelievable what the scene was – right in the middle of French soldiers. They were screw ups because I remember that night before we were driving into Paris, they were driving with all their headlights on. You don’t do this! It’s still war, you’ll get killed.

On both sides of the street, French lined the streets and French tanks lined up like a convoy firing point blank down towards the Place de la Concorde, because there was still some resistance there. I am behind one of the tanks and getting pictures of people cheering and the tanks firing.

And I know, experienced already, that if a tank is firing, someone is going to shoot back. I get my pictures and I leave, go around the corner. And my officer, he went to the spot where I was and got killed. You get that streetwise—battlewise. You are there, you do a job, and get out.

Then I went into the Place de la Concorde and there were thousands of people there already, and someone started to throw fire again, and that is when this 300-pound woman grabs me and sits on me, lying on top of me trying to get up. After that, there was no more fire.

That was the liberation of Paris.

Paris was so beautiful. The French people were beautiful, the whole world was beautiful, the weather it was fine, and we were beating the bastards and we were winning the war and we were alive and it was beautiful.

After the War

It was a long, hard war, with much death and many moments of imminent death or capture. It wasn’t something my father talked about, except for the funny bits, like finding the Calvados or the fat lady in Place de la Concorde. He came home with a boundless font of optimism and gratitude and love of America.

The post-war boom was not something that fell into the soldiers’ laps—their hard work and struggles to survive continued. New York City had a tight-post war economy and a father-son dominated photographers’ union that would not let in new members. For several years, his dream of working as a cinematographer was foiled by the union and anti-Semitism in New York’s advertising industry.

Those were just two more real-life challenges you accepted as reality and met, without whining and without building a life-long grievance. The important part was winning, not that life presented a fight.

At times, he could barely put food on the table for his family. My father, after he married, gave my mother credit for urging him to believe in himself and not give up on his dream career. Eventually, he got that dream job and became a pioneer in early TV commercials, making many of the famous commercials Baby Boomers grew up with.

The last few years of his life, my Dad’s conversations became short and repetitive, but they were quintessential Great Generation to the end: “Your Daddy’s fine. I have no major problems and no minor problems. I try not to let anything get me down. I look on the bright side of life.”

“Just roll with the punches,” he would say. “Don’t let the bastards get you down.”

His last words to us were: “I’m tough. That’s my hobby. Just keep going to the end. I’m going to jump for joy.”

Content created by the Center for American Greatness, Inc. is available without charge to any eligible news publisher that can provide a significant audience. For licensing opportunities for our original content, please contact licensing@centerforamericangreatness.com.

Photo credit: Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images