When the great Thomas Sowell retired from writing commentary in 2016, he wrapped up his farewell column this way:

With all the advances of blacks over the years, nothing so brought home to me the social degeneration in black ghettoes like a visit to a Harlem high school some years ago.

When I looked out the window at the park across the street, I mentioned that, as a child, I used to walk my dog in that park. Looks of horror came over the students’ faces, at the thought of a kid going into the hell hole which that park had become in their time.

When I have mentioned sleeping out on a fire escape in Harlem during hot summer nights, before most people could afford air-conditioning, young people have looked at me like I was a man from Mars. But blacks and whites alike had been sleeping out on fire escapes in New York since the 19th century. They did not have to contend with gunshots flying around during the night.

Sowell grew up in Harlem in the late 1930s and 1940s. I grew up in Houston in the late 1950s and 1960s. Like Sowell, I can tell of some carefree practices that would seem strange now.

Houston was a segregated city back then, but already a very large one. Yet my parents gave me the run of the town. They let me take the bus to the central library and the downtown movie palaces, and after I showed I could handle a bicycle safely in traffic, they let me ride it through all kinds of neighborhoods to distant record stores and hobby shops. It never occurred to them to be afraid of what some nogoodnik might do to me.

The only thing approaching violence I encountered was when a black kid pegged me with a BB gun from a half-block away. When the pellet bounced off my head, I just thought, “That’s pretty good shooting,” and kept on riding. Getting shot with a BB gun was no big deal; my brother had been shot in the belly, at close range, which really hurt, but the only repercussion was that we scratched the dumb redneck who shot him from our list of playmates.

What suburban family would let their boy run loose in a city the size of Houston today? This long-vanished nonchalance prevailed not only among Harlem’s poor and Houston’s middle class, but among the rich as well. Look at the older silk-stocking districts of any American city. What won’t you see surrounding them? Security gates. Rich, poor, or in-between, Americans once upon a time lived without fear of their neighbors.

Only a decade after I rambled around on a bicycle, Houston became a playground for one of the worst serial killers ever, a man who with two accomplices abducted, raped, tortured, and murdered at least 28 boys from 1970 until 1973.

Why are we not intent on undoing the social and legal changes that let such evil flourish?

Sowell’s column closed with these words:

We cannot return to the past, even if we wanted to, but let us hope that we can learn something from the past to make for a better present and future. Goodbye and good luck to all.

For many months now, I’ve been challenging Donald Trump to make good his promise that “the crime and violence that today afflicts our nation will soon—and I mean very soon—come to an end.” So far, no chorus of readers, pundits, politicians and citizens has risen to press forward that cause, and the reason may be that most Americans today are too young to remember how things were before crime assumed its present dimensions. Let us therefore “learn something from the past to make for a better present and future.” Let us recall not only what we once had in the way of law and order, but how what we had was lost.

Consider just one aspect of the problem: the revolution in criminal justice imposed on us by the U.S. Supreme Court under the leadership of Chief Justice Earl Warren.

When historian Stephen Ambrose asked former President Eisenhower to name his biggest mistake, Ike “replied heatedly, ‘The appointment of that S.O.B. Earl Warren.’ Shocked, I replied, ‘General, I always thought that was your best appointment.’ ‘Let’s not talk about it,’ he responded, and we did not.” Later, Ambrose read the “flattering and thoughtful references” to Warren in Eisenhower’s diary, and concluded that his anger at Warren resulted from the “criminal rights” cases of the 1960s, not the civil rights cases of the 1950s.

Eisenhower was hardly alone in his anger. The most controversial ruling of Warren’s tenure wasn’t Brown v. Board of Education, which the court decided on a unanimous vote in 1954. It wasn’t even the edicts against prayer and Bible readings in public school, although those raised quite a stink and in their own way may have contributed to the subsequent crime explosion. The Warren Court’s most controversial ruling, in fact, was Miranda v. Arizona (1966), the 5-4 decision that imposed on police a duty to inform a suspect of his rights before questioning him, and let the most red-handed culprit get away with the most heinous crimes if police didn’t follow procedure.

Bear in mind that Miranda didn’t create the right to remain silent. Decades before, the court had barred third-degree interrogation, the principal means of trampling that right, with no harmful effect on law enforcement. Miranda broke new ground, and its results were new, too. New, but not improved.

Writing for the court, Warren acknowledged, “the modern practice of in-custody interrogation is psychologically rather than physically oriented.” He took note of the methods prescribed by advanced police manuals and textbooks for getting around a suspect’s defenses. For example, interrogators would pretend to see things the suspect’s way. “The officers are instructed to minimize the moral seriousness of the offense, to cast blame on the victim or on society.”

Warren complained that if the suspect didn’t warm to such treatment and instead insisted on his constitutional right to say nothing at all, then the manuals advised the examiner to “concede him the right to remain silent” but to “point out the incriminating significance of the suspect’s refusal to talk.” Thus by “patience and persistence,” officers managed to draw many suspects out, eliciting alibis that wouldn’t hold up, to be followed by incriminating admissions hedged by excuses and understatement, with a complete confession frequently the end result.

In the case of Ernesto Miranda and the other criminals whose appeals were before the court, Warren conceded that “the records do not evince overt physical coercion or patent psychological ploys. The fact remains that in none of these cases did the officers undertake to afford appropriate safeguards at the outset of the interrogation to insure that the statements were truly the product of free choice.”

Warren proclaimed: “To respect the inviolability of the human personality, our accusatory system of criminal justice demands that the government seeking to punish an individual produce the evidence against him by its own independent labors, rather than by the cruel, simple expedient of compelling it from his own mouth.”

The Warren Court’s decision to overturn Miranda’s rape conviction provoked two especially bitter dissents. Justice John Marshall Harlan wrote:

Miranda’s oral and written confessions are now held inadmissible under the Court’s new rules. One is entitled to feel astonished that the Constitution can be read to produce this result. These confessions were obtained during brief, daytime questioning conducted by two officers and unmarked by any of the traditional indicia of coercion. They assured a conviction for a brutal and unsettling crime, for which the police had and quite possibly could obtain little evidence other than the victim’s identification, evidence which is frequently unreliable. There was, in sum, a legitimate purpose, no perceptible unfairness, and certainly little risk of injustice in the interrogation. Yet the resulting confessions, and the responsible course of police practice they represent, are to be sacrificed to the Court’s own finespun conception of fairness, which I seriously doubt is shared by many thinking citizens in this country.

Justice Byron White wrote that under the Fifth Amendment,

Confessions and incriminating admissions, as such, are not forbidden evidence; only those which are compelled are banned. I doubt that the Court observes these distinctions today. By considering any answers to any interrogation to be compelled regardless of the content and course of examination, and by escalating the requirements to prove waiver, the Court not only prevents the use of compelled confessions, but, for all practical purposes, forbids interrogation except in the presence of counsel. . . . The Court’s duty to assess the consequences of its action is not satisfied by the utterance of the truth that a value of our system of criminal justice is “to respect the inviolability of the human personality.” . . . More than the human dignity of the accused is involved; the human personality of others in the society must also be preserved. . . . In some unknown number of cases, the Court’s rule will return a killer, a rapist or other criminal to the streets and to the environment which produced him, to repeat his crime whenever it pleases him. As a consequence, there will not be a gain, but a loss, in human dignity.

One of those unknown future cases involved Mark Orrin Barton, a Georgia man who was “the No. 1 suspect” in the 1993 slaying of his first wife and mother in law. Strong circumstantial evidence—including an extramarital affair, a new $600,000 life insurance policy taken out on his wife, a subsequent promise to his mistress that he’d soon be free to marry her, and, after the slayings, blood stains in his car and a defensive and belligerent attitude toward investigators—all pointed his way. But under Miranda rules, he was spared a searching interrogation, and the murders went unsolved.

Six years later, Barton killed that mistress, who had been foolish enough to become his second wife, along with their two children. He then went into Atlanta and killed nine people at two day-trading offices where he had gone broke trying to “beat” the stock market. Cornered by police, he finally killed himself.

We didn’t have to wait for the Atlanta massacre to taste Miranda’s bitter fruits. They appeared immediately. Joseph Wambaugh’s nonfiction study The Onion Field gives one stark example, telling how Miranda transformed an open-and-shut prosecution of two cop killers into “the longest, most intricate court case in California history”—up to that time—resulting in “a tragic parody of crime and punishment.”

Wambaugh describes the scene as the lead investigator, Pierce Brooks, sits in his kitchen reading the state court ruling (based on Miranda’s retroactive requirements) that in 1967 overturned the killers’ initial convictions. The detective is sipping coffee, scribbling notes in the document’s margins, and getting angrier as he goes along:

Brooks’s rage knew no bounds when he got to the end of the California Supreme Court decision:

The submissive acceptance of an inquisitorial process was the desired result of a number of “techniques” used on defendants. For example, Officer Brooks maintained an air of confidence in defendants’ guilt and his “conversations” with them were often characterized as merely “a few questions” about certain “details”; yet while they began with relatively minor topics, they soon proceeded to issues central to establishing that the crime was in fact committed by these defendants . . . and each was trapped in a web of shifting explanations.

“That’s bad? That’s bad? That’s my job!” the usually unflappable detective shouted aloud in the quiet room, and his own voice startled him. Then he held the coffee cup in both hands and continued:

Most importantly, throughout these four days of questioning, Officer Brooks successfully cultivated a relationship of trust and “friendship” with these defendants, despite the fact he must have believed they had murdered one of his brother officers. Such psychological devices for extracting confessions without crossing the line of coercion were condemned by the United States Supreme Court in Miranda v. Arizona (1966).

“That shows . . . that shows,” Brooks whispered brokenly. “That proves where your head is. Where it is as far as cops are concerned!” He turned to the last pages and read:

We do not lightly reverse these judgments. We are well aware of the heinous nature of the crime involved, and of the strong indications of defendants’ guilt.

“Strong indications!” said Pierce Brooks, and threw the sheaf of papers halfway across the kitchen.

Almost seven years after their crime, the killers were convicted again and the lead killer, Gregory Powell, was sentenced again to death for the murder of Officer Ian Campbell. Campbell’s partner, Karl Hettinger, survived the abduction and shooting, but its trauma, followed by the stress especially of the second trial drove him nearly to suicide.

In 1972, Powell was saved from the gas chamber, along with Charles Manson, Sirhan Sirhan, and every other murderer then on Death Row, by the ever-beneficent U.S. Supreme Court. He died in prison in 2012, 49 years after abducting and killing Campbell—and, strangely enough, just two days after the Los Angeles intersection where the abduction took place was named Ian Campbell Square in the officer’s honor.

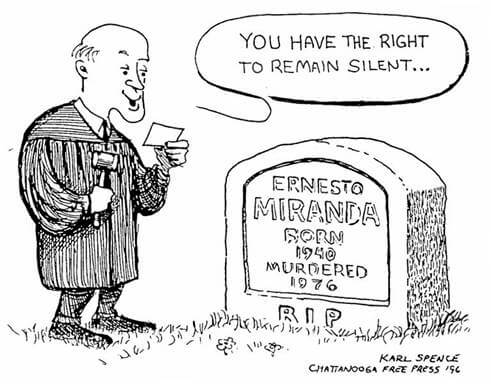

In 1976, Ernesto Miranda himself died in a fight over a poker game. Phoenix police showed up and read everyone his “Miranda rights.” Guess what? No one felt like talking. The cops shrugged. Nobody was ever punished for murdering Miranda.

Undaunted by their setbacks in court, and driven by the horrors criminals inflict on us every day in our streets, parks and homes, people kept fighting Miranda. In 1996, drawing on 25 years of courtroom experience with the rigmarole created by Miranda and kindred decisions, New York trial judge Harold J. Rothwax put in his two cents’ worth. In Guilty: The Collapse of Criminal Justice, he argued we should accept the rigmarole no longer. “Miranda has sent our jurisprudence on a hazardous detour,” he wrote. It has “accentuated just those features in our system that manifest the least regard for truth-seeking.”

In 2000, legal challenges to Miranda had finally arrived back before the U.S. Supreme Court. But the court reaffirmed Miranda, 7-2, in a ruling written by Chief Justice William Rehnquist. Rehnquist, of course, was appointed by Richard Nixon, who was elected in 1968 by voters outraged over the thing Miranda epitomizes: the Warren Court’s criminals-first, victims-second inversion of law enforcement priorities.

It appears a confession of error from our Platonic Guardians is not forthcoming anytime soon, if ever.No doubt, even the third degree would fail to extract it from them.

What does this mean for President Trump’s vow to bring today’s crime and violence to a quick end? It means nominating people like Neil Gorsuch to the Supreme Court and to lesser federal courts, while necessary, is not sufficient. Victor Davis Hanson recently wrote of how Trump is “cutting the Gordian knot” in dealing with various foreign policy challenges. There’s a big, fat Gordian knot waiting for his sword with regard to the courts, crime and punishment, too.

Photo credit: Weegee (Arthur Fellig)/International Center of Photography/Getty Images