Today our media thrives on drama and spectacle. The more “tragic” or “comedic” the event, the better. When great tragedy or comedy can serve an ideologically left-leaning agenda, then it’s a bonus. Our politics, like so much of our lives, has taken on the form of “reality” television. It’s hard to know what is real and what is put on for dramatic effect.

This is particularly true of recent commentary comparing our latest batch of current newsmakers to past figures of great political, cultural, and religious movements.

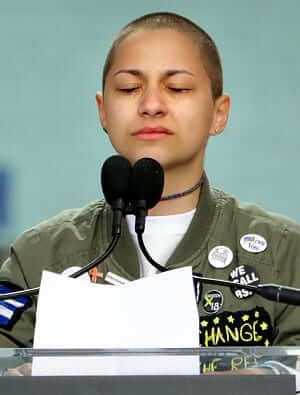

The New Yorker magazine allowed writer Rebecca Mead torture the metaphor to death in a recent issue with “Joan of Arc and the Passion of Emma González.” Mead was captivated by a moment—six minutes and 20 seconds, to be precise—when the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School student stood in silence on stage before the crowd last week at the March for Our Lives in Washington, D.C. Six minutes and 20 seconds was how long it took the shooter to murder 17 people and wound 15 others.

Almost poetically, Mead writes: “…lifting her eyes and staring into the distance before her, González stood in silence. Inhaling and exhaling deeply—the microphone caught the susurration, like waves lapping a shoreline—González’s face was stoic, tragic…tears rolled down her cheeks; she did not wipe them away.” Mead’s intent is not to simply describe this seemingly intense and honest moment. Rather, she goes on explicitly to call out González’s “performance,” and compare it to that of Renee Maria Falconetti in Carl Theodor Dreyer’s classic silent film, “The Passion of Joan of Arc” (1928).

“In its restraint, its symbolism, and its palpable emotion, González’s silence was a remarkable piece of political expression,” Mead writes. She then describes Falconetti’s performance as Joan of Arc and the most significant moment in the film when she is being burned at the stake for heresy. Mead notes how Falconetti does not speak a word and that all of her expressions are seen in her face. This is supposed to be one of the reasons González and Falconetti (and Joan of Arc) are so much alike. Silence and a shaved head.

Mead forgets, however, that from an aesthetic and technical point of view, “The Passion of Joan of Arc” is a silent film and silent cinema relies almost completely on facial and bodily expressions to convey any message to the audience.

Of course, the final moments of Joan of Arc depicted in the film will be more intense than, say, Charlie Chaplin or Buster Keaton tripping on a banana peel. Even so, Mead shows no knowledge about silent cinema. Her claim appears to be entirely driven by some notion of aesthetic activism rather than reality.

The lack of proper reflection on the film itself is a minor concern. The major problem in Mead’s article is that she implicitly compares González’s tears and, one assumes, her acts, with those of St. Joan. But Joan of Arc died for her faith. She was a martyr. The gravity of this act, the courage she had, and the power this gave her over her oppressors simply is not comparable to anything that Emma González may have done.

Mead’s intent is to show great courage and perhaps even sacrifice on González’s part but she digs a hole for herself when she unwittingly reduces González and her pain to a “political expression” and “performance.” In the event that González was just engaged in a theatrical performance, then we have to take it for what it is. There is no shred of honesty, only manipulation of images to evoke a certain response from the people.

You might say that this is what the film does as well. Of course! But the difference is that Falconetti is portraying a real historical figure, whereas Mead has constructed a mystical persona around González, effectively making her into an ideological saint.

Since today’s ideologues are fond of pointing out crimes of cultural appropriation, isn’t Mead’s commentary an example of religious appropriation?

Another and far deeper layer of the problem in Mead’s take is the question of reality. We are seeing language and images manipulated every day in order to keep the ideological left alive. At this point, so much of it has become gibberish. Protests are, to borrow Tom Wolfe’s term, part of the “radical chic.” Today’s moments of “radicalism” and “anti-authoritarianism,” (such as March for Our Lives or the Women’s March) are poor facsimiles of the 1960s originals. They feel more like a nostalgic style, like tie-dye and fringe, put on by today’s young wannabe activists, in part because such moments are so easily captured, sentimentalized, and featured on Instagram to generate likes and social approval.

And yet, for all the creation of false communities, we are more isolated from each other. The words and signs we throw at each other have no concrete or real connection to the past. They only ensure a troubled and possibly dystopian future. If the majority of people knew or understood any truly heroic precedent—if we had anything resembling a common culture—then someone like Mead would not get away with foolishly comparing Emma González with Joan of Arc. Or maybe I am being naïve. Maybe Mead knows exactly what she is doing. In one exhausting gesture, she is not only creating an ideological saint that is part of the godless church of leftism, she is also attempting to destroy the theological and spiritual meaning of the deep life of Joan of Arc.

History shows us moments of great drama but there is a significant difference between the drama of reality and the drama of a falsehood. Joan of Arc lived a life of authenticity and fearlessness. Death was only the beginning for her. The passion she displayed was not some ordinary burst of energy or half-baked emotion. It is the passion of the cross. Joan of Arc carried the burden of her cross, emulating Christ in his own sacrifice. Her deeds act reflected the reality of humanity in all its glory, elation, and profound sorrow. Her martyrdom was an act of Christian mystery—of human wonder at who God is and a reflection of sacrifice itself.

Let us not confuse the theological drama that continues to have meaning for Christians with the ideological and politically motivated political theater of unintelligible absurdity.

Photo credits: Movie Poster Image Art/Getty Images (top); Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images (above right)