A few weeks ago I met a man with backwards feet.

A few weeks ago I met a man with backwards feet.

This was in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, halfway through a vacation in Southeast Asia. It was at a dingy old-school gym with rusty weights and a corrugated tin roof that made a thunderous racket when it rained. A frail, middle-aged man sat at a counter and collected the $1 entrance fee. The place was just a few blocks from my hotel, and it felt good to throw around some iron after several days of casual sightseeing. It was on my second visit when the man at the front desk got up to tend to some errand, and I noticed the reason for his limping gait: his feet were simply the wrong way around. One doesn’t see that in the United State or other developed nations. Such a birth defect would be corrected in infancy, as soon as surgically feasible. Not so in Cambodia.

My previous stop had been Bangkok, Thailand. On the street level, the two capital cities are similar: teeming, chaotic traffic, all-but-impassable sidewalks thronged with merchants, parked vehicles, and the ubiquitous food stands selling spicy soup, grilled fish, and exotic fruits.

Gazing upward, however, the differences become stark. Bangkok is a metropolis, its downtown thick with modern skyscrapers. Phnom Penh is mostly flat. Apart from a few medium-tall buildings, almost nothing in the city rises above five stories. Whatever other factors explain this underdevelopment, a primary one is surely catastrophe wrought by the communist Khmer Rouge during their iron grip on Cambodia from 1975 to 1979, when an estimated one-quarter to one-third of the population perished from forced labor, starvation, or execution.

Many people are familiar with the Khmer Rouge “killing fields.” But some of the worst atrocities were committed at Prison Site 21 in Phnom Penh, now called the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum (after the name of the high school it had been). It is a grim place to visit. According to Pol Pot’s perverse utopianism, Cambodian society was to be re-started at “Year Zero” on the basis of the “Old People”—the uncorrupted rural peasants. “New People”—urban dwellers, professionals, monks, and intellectuals (anyone wearing eyeglasses was ipso facto an intellectual and subject to arrest)—were to be expunged; but only after providing an adequate confession of their anti-revolutionary crimes. Some 20,000 victims endured torture and death at Tuol Sleng to fulfill this ideological mandate.

Upon seizing the facility, Pol Pot’s men subdivided most of the school’s classrooms into tiny brick cells. The windows and ventilation shafts were boarded up. Each unit held two inmates, shackled to the floor in leg irons. In the dark, suffocating heat, unwashed, unfed, unable to move, the terrified prisoners were taken from their cells only to face the even greater torment of interrogation. I offer one gruesome example. [Warning: this is graphic. Some readers may wish to skip to the next paragraph.] In the pretty school courtyard where 50 year-old mango trees still grow, there is a wooden frame some 25 feet high, now called “the gallows” The school had built it and attached ropes to iron rings on the cross-beam, for the students to practice climbing. The Khmer Rouge used it for a different purpose. Prisoners were bound with their hands behind their backs and then hoisted up on the ropes, often dislocating their shoulders. If, or when, they passed out from the pain, they would be flipped over and dunked head-first into large pots of human waste. The instinctive revulsion to this often revived the prisoner and they were then flipped back up, where the interrogation was resumed.

Officially, inmates were not supposed to die under torture. Only after the guards decided, at some arbitrary point, that a prisoner had made a sufficient apology would an execution order be signed by the prison commandant—the unspeakably wicked Comrade Duch. On one death warrant for 17 children and teenagers, he wrote, “Smash them to pieces.” Duch, whose real name is Kang Kek Iew, is still alive, alas. Now 74, he is serving a life sentence in a Cambodian penitentiary. May he soon rot in Hell.

Under torture, of course, many prisoners confabulated stories they thought would satisfy the guards and ease the pain. In 1978, a New Zealand swimmer and surfer name Kerry Hamill sailed too close to Cambodian waters, was captured by the Khmer Rouge and along with his shipmate was swept into the nightmare of Tuol Sleng. Under interrogation Hamill said that his CIA handler was “Colonel Sanders.” The guards—unfamiliar with Western popular culture or fast food—duly noted this in his confession. Like nearly every other prisoner, Hamill was killed and his body destroyed. In fact, only seven inmates (out of 20,000!) somehow managed to survive.

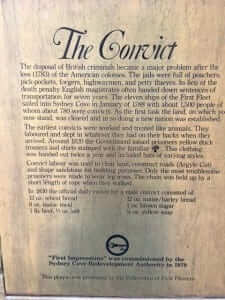

After Phnom Penh, my next stop was Sydney—the site of Britain’s first Australian penal colony. (I did not plan my vacation as an international prison tour. I went to Sydney for the usual reasons, having more or less forgotten its historical origins.) On the edge of the beautiful harbor, a popular tourist attraction known as “The Rocks” preserves some of the original structures and describes the conditions of the early settlement. One explanatory marker I found particularly interesting was this plaque.

A few things are worth noting. First, the word “convicts” necessarily implies a conviction—the end result of at least some rudimentary due process, were evidence or proof of an actual crime has been brought forth. Second, though the plaque says the convicts were “treated and worked like animals,” note the list of rations at the bottom (including a pound of beef (!) and a portion of soap every day). Convicts were required to perform hard physical labor, but the British had the decency to know that if you work men, you need to feed them—which they did.

Additionally, neither at The Rocks nor online could I find a single allegation that these prisoners were subjected to the random, stomach-turning abuse that was not merely a daily, even hourly, occurrence at Tuol Sleng, but its very purpose. Finally, consider that the first penal colony at Sydney was established in 1788, some 190 years before Enlightenment and Progress plunged Cambodia into unprecedented barbarism.

Let me conclude this rambling travelogue with a few brief observations, now that I’m back in the United States and more or less over my jetlag. First, my patience for inane blather about a Trump dictatorship—minimal to begin with—is now nil. The next time I hear someone hyperventilating about incipient tyranny, I’ll simply say, “Google ‘Tuol Sleng,’ and explain why Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton don’t seem particularly worried about having their shoulders dislocated in a high school courtyard.”

On a more positive note, I find myself in fresh awe at the miracle of being an American. If there is one concession I would make to the liberal critique of conservatives it is that we can be too complacent, too uninterested in the daily lives of people abroad. I now believe it is vital to travel, especially to less developed countries, to truly appreciate how remarkable is our Greek, Roman, and English inheritance of liberty and law.

And to friend and foe alike, let me humbly suggest that the next time you count your blessings, try to imagine some of the things you never thought to be thankful for—like two straight feet.